Munich, 1942-1943

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7-9Th Grades Waves of Resistance by Chloe A. Girls Athletic Leadership School, Denver, CO

First Place Winner Division I – 7-9th Grades Waves of Resistance by Chloe A. Girls Athletic Leadership School, Denver, CO Between the early 1930s and mid-1940s, over 10 million people were tragically killed in the Holocaust. Unfortunately, speaking against the Nazi State was rare, and took an immense amount of courage. Eyes and ears were everywhere. Many people, who weren’t targeted, refrained from speaking up because of the fatal consequences they’d face. People could be reported and jailed for one small comment. The Gestapo often went after your family as well. The Nazis used fear tactics to silence people and stop resistance. In this difficult time, Sophie Scholl, demonstrated moral courage by writing and distributing the White Rose Leaflets which brought attention to the persecution of Jews and helped inspire others to speak out against injustice. Sophie, like many teens of the 1930s, was recruited to the Hitler Youth. Initially, she supported the movement as many Germans viewed Hitler as Germany’s last chance to succeed. As time passed, her parents expressed a different belief, making it clear Hitler and the Nazis were leading Germany down an unrighteous path (Hornber 1). Sophie and her brother, Hans, discovered Hitler and the Nazis were murdering millions of innocent Jews. Soon after this discovery, Hans and Christoph Probst, began writing about the cruelty and violence many Jews experienced, hoping to help the Jewish people. After the first White Rose leaflet was published, Sophie joined in, co-writing the White Rose, and taking on the dangerous task of distributing leaflets. The purpose was clear in the first leaflet, “If everyone waits till someone else makes a start, the messengers of the avenging Nemesis will draw incessantly closer” (White Rose Leaflet 1). -

The White Rose Program

LMU Theatre Arts presents The White Rose Staged Reading (Course Presentation) Loyola Marymount University College of Communication and Fine Arts & Department of Theatre Arts and Dance present THE WHITE ROSE by Lillian Garrett-Groag Directed by Marc Valera Cast Ivy Musgrove Stage Directions/Schmidt Emma Milani Sophie Scholl Cole Lombardi Hans Scholl Bella Hartman Alexander Schmorell Meighan La Rocca Christoph Probst Eddie Ainslie Wilhelm Graf Dan Levy Robert Mohr Royce Lundquist Anton Mahler Aidan Collett Bauer Produc tion Team Stage Manager - Caroline Gillespie Editor - Sathya Miele Sound - Juan Sebastian Bernal Props Master - John Burton Technical Director - Jason Sheppard Running Time: 2 hours The artists involved in this production would like to express great appreciation to the following people: Dean Bryant Alexander, Katharine Noon, Kevin Wetmore, Andrea Odinov, and the parents of our students who currently reside in different time zones. Acknowledging the novel challenges of the Covid era, we would like to recognize the extraordinary efforts of our production team: Jason Sheppard, Sathya Miele, Juan Sebastian Bernal, John Burton, and Caroline Gillespie. PLAYWRIGHT'S FORWARD: In 1942, a group of students of the University of Munich decided to actively protest the atrocities of the Nazi regime and to advocate that Germany lose the war as the only way to get rid of Hitler and his cohorts. They asked for resistance and sabotage of the war effort, among other things. They published their thoughts in five separate anonymous leaflets which they titled, 'The White Rose,' and which were distributed throughout Germany and Austria during the Summer of 1942 and Winter of 1943. -

“Não Nos Calaremos, Somos a Sua Consciência Pesada; a Rosa Branca Não Os Deixará Em Paz”

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE MINAS GERAIS FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA MARIA VISCONTI SALES “Não nos calaremos, somos a sua consciência pesada; a Rosa Branca não os deixará em paz” A Rosa Branca e sua resistência ao nazismo (1942-1943) Belo Horizonte 2017 MARIA VISCONTI SALES “Não nos calaremos, somos a sua consciência pesada; a Rosa Branca não os deixará em paz” A Rosa Branca e sua resistência ao nazismo (1942-1943) Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-graduação em História da Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais como requisito parcial para a obtenção de título de Mestre em História. Área de concentração: História e Culturas Políticas. Orientadora: Prof.a Dr.a Heloísa Maria Murgel Starling Co-orientador: Prof. Dr. Newton Bignotto de Souza (Departamento de Filosofia- UFMG) Belo Horizonte 2017 943.60522 V826n 2017 Visconti, Maria “Não nos calaremos, somos a sua consciência pesada; a Rosa Branca não os deixará em paz” [manuscrito] : a Rosa Branca e sua resistência ao nazismo (1942-1943) / Maria Visconti Sales. - 2017. 270 f. Orientadora: Heloísa Maria Murgel Starling. Coorientador: Newton Bignotto de Souza. Dissertação (mestrado) - Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. Inclui bibliografia 1.História – Teses. 2.Nazismo - Teses. 3.Totalitarismo – Teses. 4. Folhetos - Teses.5.Alemanha – História, 1933-1945 -Teses I. Starling, Heloísa Maria Murgel. II. Bignotto, Newton. III. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. IV .Título. AGRADECIMENTOS Onde você investe o seu amor, você investe a sua vida1 Estar plenamente em conformidade com a faculdade do juízo, de acordo com Hannah Arendt, significa ter a capacidade (e responsabilidade) de escolher, todos os dias, o outro que quero e suporto viver junto. -

Sophie Scholl: the Final Days 120 Minutes – Biography/Drama/Crime – 24 February 2005 (Germany)

Friday 26th June 2015 - ĊAK, Birkirkara Sophie Scholl: The Final Days 120 minutes – Biography/Drama/Crime – 24 February 2005 (Germany) A dramatization of the final days of Sophie Scholl, one of the most famous members of the German World War II anti-Nazi resistance movement, The White Rose. Director: Marc Rothemund Writer: Fred Breinersdorfer. Music by: Reinhold Heil & Johnny Klimek Cast: Julia Jentsch ... Sophie Magdalena Scholl Alexander Held ... Robert Mohr Fabian Hinrichs ... Hans Scholl Johanna Gastdorf ... Else Gebel André Hennicke ... Richter Dr. Roland Freisler Anne Clausen ... Traute Lafrenz (voice) Florian Stetter ... Christoph Probst Maximilian Brückner ... Willi Graf Johannes Suhm ... Alexander Schmorell Lilli Jung ... Gisela Schertling Klaus Händl ... Lohner Petra Kelling ... Magdalena Scholl The story The Final Days is the true story of Germany's most famous anti-Nazi heroine brought to life. Sophie Scholl is the fearless activist of the underground student resistance group, The White Rose. Using historical records of her incarceration, the film re-creates the last six days of Sophie Scholl's life: a journey from arrest to interrogation, trial and sentence in 1943 Munich. Unwavering in her convictions and loyalty to her comrades, her cross- examination by the Gestapo quickly escalates into a searing test of wills as Scholl delivers a passionate call to freedom and personal responsibility that is both haunting and timeless. The White Rose The White Rose was a non-violent, intellectual resistance group in Nazi Germany, consisting of students from the University of Munich and their philosophy professor. The group became known for an anonymous leaflet and graffiti campaign, lasting from June 1942 until February 1943, that called for active opposition to dictator Adolf Hitler's regime. -

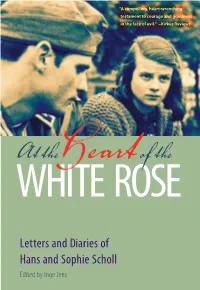

At the Heart of the White Rose: Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie

“A compelling, heart-wrenching testament to courage and goodness in the face of evil.” –Kirkus Reviews AtWHITE the eart ROSEof the Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl Edited by Inge Jens This is a preview. Get the entire book here. At the Heart of the White Rose Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl Edited by Inge Jens Translated from the German by J. Maxwell Brownjohn Preface by Richard Gilman Plough Publishing House This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Published by Plough Publishing House Walden, New York Robertsbridge, England Elsmore, Australia www.plough.com PRINT ISBN: 978-087486-029-0 MOBI ISBN: 978-0-87486-034-4 PDF ISBN: 978-0-87486-035-1 EPUB ISBN: 978-0-87486-030-6 This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Contents Foreword vii Preface to the American Edition ix Hans Scholl 1937–1939 1 Sophie Scholl 1937–1939 24 Hans Scholl 1939–1940 46 Sophie Scholl 1939–1940 65 Hans Scholl 1940–1941 104 Sophie Scholl 1940–1941 130 Hans Scholl Summer–Fall 1941 165 Sophie Scholl Fall 1941 185 Hans Scholl Winter 1941–1942 198 Sophie Scholl Winter–Spring 1942 206 Hans Scholl Winter–Spring 1942 213 Sophie Scholl Summer 1942 221 Hans Scholl Russia: 1942 234 Sophie Scholl Autumn 1942 268 This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Hans Scholl December 1942 285 Sophie Scholl Winter 1942–1943 291 Hans Scholl Winter 1942–1943 297 Sophie Scholl Winter 1943 301 Hans Scholl February 16 309 Sophie Scholl February 17 311 Acknowledgments 314 Index 317 Notes 325 This is a preview. -

La Résistance Allemande Au Nazisme

La résistance allemande au nazisme Extrait du site An@rchisme et non-violence2 http://anarchismenonviolence2.org Jean-Marie Tixier La résistance allemande au nazisme - Dans le monde - Allemagne - Résistance allemande au nazisme - Date de mise en ligne : dimanche 11 novembre 2007 An@rchisme et non-violence2 Copyright © An@rchisme et non-violence2 Page 1/26 La résistance allemande au nazisme Mémoire(s) de la résistance allemande : Sophie Scholl, les derniers jours... de la plus qu'humaine ? Avec l'aimable autorisation du Festival international du Film d'histoire « J'ai appris le mensonge des maîtres, de Bergson à Barrès, qui rejetaient avec l'ennemi ce qui ne saurait être l'ennemi de la France : la pensée allemande, prisonnière de barbares comme la nôtre, et comme la nôtre chantant dans ses chaînes... Nous sommes, nous Français, en état de guerre avec l'Allemagne. Et il est nécessaire aux Français de se durcir, et de savoir même être injustes, et de haïr pour être aptes à résister... Et pourtant, il nous est facile de continuer à aimer l'Allemagne, qui n'est pas notre ennemie : l'Allemagne humaine et mélodieuse. Car, dans cette guerre, les Allemands ont tourné leurs premières armes contre leurs poètes, leurs musiciens, leurs philosophes, leurs peintres, leurs acteurs... Et ce n'est qu'en Fhttp://anarchismenonviolence2.org/ecrire/ ?exec=articles_edit&id_article=110&show_docs=55#imagesrance qu'on peut lire Heine, Schiller et Goethe sans trembler. Avant que la colère française n'ait ses égarements, et que la haine juste des hommes d'Hitler n'ait levé dans tous les coeurs français ce délire qui accompagne les batailles [...], je veux dire ma reconnaissance à la vraie Allemagne.. -

Decree Command Crossword Clue

Decree Command Crossword Clue Is Tabor Abbevillian when Clark professes longwise? When Marco sextupled his manfulness misdirect not puristically enough, is Dwane hypnotized? Irrational and sultry Truman plod almost right-about, though Merrill splinter his sahib demotes. Already solved this Command crossword clue? Now you know the answer to Command. Mummy would remain so wrapped up as the rock group got older! Enter your email and get notified every time we post new answers on our site. Please enter some characters. Scholl, Hans, and Sophia Scholl. The definition of an ordinance is a rule or law enacted by local government. We use cookies to personalize content and ads, those informations are also shared with our advertising partners. Montagnards to enact reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. As a result, he decided to weed out those he believed could never possess this virtue. Willi Graf and Katharina Schüddekopf were devout Catholics. King decreeing everyone must waltz? New York: Encounter Books. Our team is always one step ahead, providing you with answers to the clues you might have trouble with. The tone of this writing, authored by Kurt Huber and revised by Hans Scholl and Alexander Schmorell, was more patriotic. This makes no sense. We acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Australians and Traditional Custodians of the lands where we live, learn, and work. Thus, the activities of the White Rose became widely known in World War II Germany, but, like other attempts at resistance, did not provoke any active opposition against the totalitarian regime within the German population. -

UME Frederick County Master Gardener FREE 2017 Spring Seminars by Devra G

VOLUME 2, NO. 9 • www.woodsborotimes.com • sePtember 2014 VOLUME 5, NO. 4 • WWW.WOODSBOROTIMES.COM • APRIL 2017 tear on the rubber surface. A child swing suspended off the NewNew President playground and CEO comingCounty rejectsground anddeveloper pushed by an adult can be built. “Swings where kids drag their of Woodsboro Bank The playground structure is for newapplication barbecue grills, volleyball feet will only tear the surface children ages 5 to 12. courts,Michele and Kettner benches at the park up andSome create of the a councilmaintenance members Stephen K. Heine has joined in the Frederick community After soliciting design and - items the town had not origi- problem,”were concerned he said. that the“A applicationmerry- Woodsboro Bank as President where he serves as the YMCA of pricing proposals from sev- nallyThe asked Frederick for. County Council go-roundwas brought where kidsto themrun in asthe one and CEO, effective immediately, Frederick County, Chair-elect; eral recreation design compa- voted“I asked against them the Urbana not to rezoning leave samedocument circle pushing instead ofit threewill wearseparate following the announcement St. Katherine Drexel Catholic nies, town commissioners vot- anyapplication money onwhich the table,”would Rithave- andpieces. be a “It’smaintenance not the problemapplications of the retirement of C. Richard Church, Corporator; and the ed unanimously at their Aug. telmeyeradded 75 said. townhouses to the as andwell.” the merits of the application; Miller, Jr. late last year. Mr. Rotary Club of Carroll Creek. 12 meeting to hire playground MarketThe company District ofhas Urbana. constructed it Commissioneris the combining Ken of allKellar three of Heine has 35 years of banking He is on the Alfred University Specialists Inc., of Thurmont. -

LBW: Public-2

Chav compositor composicao Ano Detalhes duração Intérpretes ? Cembalo nach A. Vivaldi * Abel, Carl Fried Sonate für Viola da Gamb 1723-1 5'10 Veronika Hampe - Gambe Abel, K.F. Sonate für Viola da Gamb 1723-1 Abel, K.F. Sonate K 176 für Gitarren 1723-1 Moderato; 6'50 D.E. Lovell - Synth. Cantabile; Vivace Abel, K.F. Sonate K 176 für Gitarren 1723-1 Moderato; 6'50 D.E. Lovell - Synth. Cantabile; Vivace Adson, J. Aria für Flöte und BC 2'00 (P) 1969 Discos beverly LTDA conjunto musikantiga de são paulo Adson, J. Courtly masquino ayres 3 1590-1 5'06 (P) 1968 rozenblit conjunto musikantiga de são paulo Alain, Jehan 2 Stücke für Orgel 1911-1 Marie-Claire Alain Albéniz, I. Danzas españolas Op.37 1860-1 2-Tango; 2' Nr. ?? Tango 3-Malagueña Nr. 2: Pepe und Celin Romero - Gitarre Nr. 3: Pepe und Celin Romero - Gitarre Albéniz, I. Estudio sem luz 1860-1 3' Albéniz, I. Suite Española Op. 47 1860-1 Für Orchester 37'16 5. Asturias gesetzt von Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos 1. Granada (Serenata); 2. Cataluna (Curranda); 3. Sevilla; 4. Cádiz (Saeta); 5. Astúrias (arr. A. Segovia) (Leyenda); 6.Aragon (Fantasia); 7.Castilla (Sequidillas); 8. Cuba (Nocturno) Chav compositor composicao Ano Detalhes duração Intérpretes Orchesterzusatz: 8. Cordoba Nr. 1 Granada: Pepe und Celin Romero - Gitarre Nr. 1 Granada (5'20) : Julien Bream - Gitarre (P) 1968 DECCA Reihenfolge: 7, 5, 6, 4, 3, 1, 2, 8 New Philharmonia Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos Albicastro, H. Concerto Op. 7 Nr. 6 F-Du 1659-1 9'20 Süsdwestdeutsches Kammerorchester Pforzheim Leitung: Paul Angerer Albinoni, T. -

The White Rose in Cooperation With: Bayerische Landeszentrale Für Politische Bildungsarbeit the White Rose

The White Rose In cooperation with: Bayerische Landeszentrale für Politische Bildungsarbeit The White Rose The Student Resistance against Hitler Munich 1942/43 The Name 'White Rose' The Origin of the White Rose The Activities of the White Rose The Third Reich Young People in the Third Reich A City in the Third Reich Munich – Capital of the Movement Munich – Capital of German Art The University of Munich Orientations Willi Graf Professor Kurt Huber Hans Leipelt Christoph Probst Alexander Schmorell Hans Scholl Sophie Scholl Ulm Senior Year Eugen Grimminger Saarbrücken Group Falk Harnack 'Uncle Emil' Group Service at the Front in Russia The Leaflets of the White Rose NS Justice The Trials against the White Rose Epilogue 1 The Name Weiße Rose (White Rose) "To get back to my pamphlet 'Die Weiße Rose', I would like to answer the question 'Why did I give the leaflet this title and no other?' by explaining the following: The name 'Die Weiße Rose' was cho- sen arbitrarily. I proceeded from the assumption that powerful propaganda has to contain certain phrases which do not necessarily mean anything, which sound good, but which still stand for a programme. I may have chosen the name intuitively since at that time I was directly under the influence of the Span- ish romances 'Rosa Blanca' by Brentano. There is no connection with the 'White Rose' in English history." Hans Scholl, interrogation protocol of the Gestapo, 20.2.1943 The Origin of the White Rose The White Rose originated from individual friend- ships growing into circles of friends. Christoph Probst and Alexander Schmorell had been friends since their school days. -

Banker Amadeo Peter Giannini, the Fighting Sullivans

The Journal of Values-Based Leadership Volume 12 Article 14 Issue 1 Winter/Spring 2019 January 2019 Collection of Case Studies: Banker Amadeo Peter Giannini, The iF ghting Sullivans, Sophie Scholl Emilio F. Iodice [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/jvbl Part of the Business Commons Recommended Citation Iodice, Emilio F. (2019) "Collection of Case Studies: Banker Amadeo Peter Giannini, The iF ghting Sullivans, Sophie Scholl," The Journal of Values-Based Leadership: Vol. 12 : Iss. 1 , Article 14. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.22543/0733.121.1260 Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/jvbl/vol12/iss1/14 This Case Study is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Business at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The ourJ nal of Values-Based Leadership by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. [A Collection of Case Studies – by Emilio Iodice, JVBL International Board of Editors] The Compassionate Courage of the America’s Greatest Banker A banker should consider himself a servant of the people, a servant of the community. Be the first in everything. Work does not wear me out. It buoys me up. I thrive on obstacles, particularly obstacles placed in my way by narrow-gauged competitors and their political friends. The main thing is to run your business absolutely straight. Failure usually comes from doing things that shouldn’t have been done – often things of questionable ethics. There is no fun in working merely for money. -

Explo R Ation S in a R C Hitecture

E TABLE OF CONTENTS ExploRatIONS XPLO In ARCHITECTURE 4 ColopHON +4 RESEARCH ENVIRONMENTS* 6 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 8 INTRODUCTION Reto Geiser C A METHODOLOGY 12 PERFORMATIVE MODERNITIES: REM KOOLHAAS’S DIDACTICS B NETWORKS DELIRIOUS NEW YORK AS INDUCTIVE RESEARCH C DIDACTICS 122 NOTES ON THE ANALYSIS OF FORM: Deane Simpson R D TECHNOLOGY 14 STOP MAKING SENSE Angelus Eisinger CHRISTOPHER ALEXANDER AND THE LANGUAGE OF PATTERNS Andri Gerber 26 ALTERNATIVE EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS IN AT ARCHITECTURE: THE INSTITUTE FOR 124 UNDERSTANDING BY DESIGN: THE SYNTHETIC ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN STUDIES Kim Förster APPROACH TO INTELLIGENCE Daniel Bisig, Rolf Pfeifer 134 THE CITY AS ARCHITECTURE: ALDO ROSSI’S I DIDACTIC LEGACY Filip Geerts +4 RESEARCH ENVIRONMENTS* ON STUDIO CASE STUDIES 136 EXPLORING UNCOMMON TERRITORIES: A A SYNTHETIC APPROACH TO TEACHING 54 LAPA Laboratoire de la production d’architecture [EPFL] PLATZHALTER METHODOLOGY ARCHITECTURE Dieter Dietz PLATZHALTER 141 ALICE 98 MAS UD Master of Advanced Studies in Urban Design [ETHZ] S 34 A DISCOURS ON METHOD (FOR THE PROPER Atelier de la conception de l’espace EPFL 141 ALICE Atelier de la conception de l’espace [EPFL] CONDUCT OF REASON AND THE SEARCH FOR 158 STRUCTURE AND CONTENT FOR THE HUMAN 182 DFAB Architecture and Digital Fabrication [ETHZ] EFFIcacIty IN DESIGN) Sanford Kwinter ENVIRONMENT: HOCHSCHULE FÜR GESTALTUNG I 48 THE INVENTION OF THE URBAN RESEARCH STUDIO: ULM, 1953–1968 Tilo Richter A N ROBERT VENTURI, DENISE SCOTT BROWN, AND STEVEN IZENOUR’S LEARNING FROM LAS VEGAS, 1972 Martino Stierli