Sir John Davies, Orchestra Brief Chronicles VII (2016) Ii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1952-02-21

On The Inside , The ' Weather 1IIl-'b' doud, &lUI con Sorority Ruahinq Schedule .. , Umaecl cold ....,. with. Paqa 3 oceuioDai 1Irh& mow 27 Game Baseball Card '" . Ouri_ • ..aI, dewI, '" Paqe' aDd Dol Ilaile _ eeId Car ..r ConfarancH at owan t"rida,. Jlirh &ocIa" 3.; ... Paqa 6 loW. 11. Wah WeUncia)", • %I; low, ZL Eat. 1868 - AP Lecued Wire. AP Wirepboto - Five Cents Iowa City. Iowa. Thuraday. February 21. 1952 - Vol. 86. No. 99 · n f . Clothing Salesman E, : ~ropean L/,e ,ense New Hero in Capture Senate Group Approves 1 l ' . UMT , . D bl Of Robber SuHon . is aln -' r;~ ~O em NEW YORK (II')-A tall, young I.'M . • clothing salesman with a memory Provides, for 81 [or faces fumed up Wednesday as Bill Plan :. " :" " o' u.n' CI the unsung hero In the capture of ( notorious Wlllie sutton. To Start by' Year's End Of NATO He is 24-year-old Arnold Schus WASHINGTON (II') - Universal military &ralning for 18-year , ter, who tipped ort Brooklyn , olds moved a long stride nearer reality Wednesday. , LISBON, Portugal (IP) - Atlantic Pact ministers met ill Lisbon pOlice Monday that a man he'd By a 12-0 vote, the senate armed 5eI'Vica committee approved a Io ·try to translate "armies on paper into armies in the field." The bill to permit the start of UMT before the end of the year. words were those of Secretary of State Dean Acheson Sutton/s Pal .Captured The correspondlnl house com· the Allied powers "What we have done 'so far mittee earlier had approved 3 unless we finish tbe job." ---'-------~-- NEW YORK (JP)-Pollce Com Today Is Last Day similar measure. -

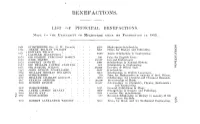

Benefactions

BENEFACTIONS. LIST (.iV PKilSTClTAL BENEFACTIONS. MAIM-: T<> TH.K UNIVKKSITY OK MELBOURNE SINOK ITS FOUNDATION IN 1S53. ISM SI.'IISCRIHEUS CSir. <i. W. IIUMIKX) ,tS.r'C Shilki.'spi.-arc Seln'Iai'ship. l,;7i IIENKV Tnl.MAN IrWUiHT fil 101' Rrizns for History and Education. -, l EHWARI1 WILSON" , '' ' "i LAC 11 LAN MACKINNON. ' 10(10 Avails Scholarship in Enu'itiL'iM-iii--. 1ST:; 'SIR CKllltliE l-'EIKilisr r.V HnWEN 1UII I'r-izu for English Essay. 1*7:; JOHN HASTIE .... I,s7:i OODI-'REY IK>\\ ITX Ill, till (IClli'l'lll KlllliiU'llltlllt 1S7:; Sill. WILLIAM l-'OSTKI! STAWELL 'WOO Scholarships hi N'lilnral History, ISS7:". SIK. SAMUEL WlLS'iN ririi'i Scholarship hi lOnirin^i'rin^. !*>:; JOHN IUXSON WYSELASKIE - Hfr.llllir Erection nf Wilson Hull. is.vl WILLIAM THOMAS Mi 1I.I.IS1 IX xnlO Scholarships 1,<S1 StinSCRIIiERS .... rilluli Scholarships in .Modern Luii^iiiiffcs. P-S7 WILLIAM CHARLES EEliXnT - l.Mi I'ri/n for- Mathematics in memory nf I'rof. Wilson, ls>7 l-'liANCIS ORMOMIl -.alilo Scholarships for Physical and Chemical .Re.Keareli. isrni Hi'rHERT lil.XSIlN L'II.OOII I'iorcssorship of Music. 10,s:r7 Scholarships in Chemistry, Physics, Mathematics IS'" SLUSCIUDERS .... .•mil (-'.nuiiiL'i-'i'iii^. ,ri-17 Onnnnd Kxhihitions in Musi'-. IS!U JAMES CEIIKCiE HEAXEY :{!li.m Scholarships in Snrjrevy und Pathology. l.V.M I.1AVH1 KAY o7(;l .Caroline Kuy Scholarsnips, 1WI7 SUHSOlill.iERS 7;•'l,-l Research Scholarship in biology in memory of Sir .lames MacHain, I'.mj ROMERT ALEXANDER WHICHT lin'.o Prizes lor Music and ffir Mechanical Kn'.riiicel-inir. -

The New Cambridge Shakespeare

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82544-3 - The Merchant of Venice Edited by M. M. Mahood Frontmatter More information THE NEW CAMBRIDGE SHAKESPEARE GENERAL EDITOR Brian Gibbons ASSOCIATE GENERAL EDITOR A. R. Braunmuller, University of California, Los Angeles From the publication of the first volumes in 1984 the General Editor of the New Cambridge Shakespeare was Philip Brockbank and the Associate General Editors were Brian Gibbons and Robin Hood. From 1990 to 1994 the General Editor was Brian Gibbons and the Associate General Editors were A. R. Braunmuller and Robin Hood. THE MERCHAnt OF VENICE The Merchant of Venice has been performed more often than any other comedy by Shakespeare. Molly Mahood pays special attention to the expectations of the play’s first audience, and to our modern experience of seeing and hearing the play. In a substantial new addition to the Introduction, Charles Edelman focuses on the play’s sex- ual politics and recent scholarship devoted to the position of Jews in Shakespeare’s time. He surveys the international scope and diversity of theatrical interpretations of The Merchant in the 1980s and 1990s and their different ways of tackling the troubling figure of Shylock. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82544-3 - The Merchant of Venice Edited by M. M. Mahood Frontmatter More information THE NEW CAMBRIDGE SHAKESPEARE All’s Well That Ends Well, edited by Russell Fraser Antony and Cleopatra, edited by David Bevington As You Like It, edited by Michael Hattaway The Comedy of Errors, edited by T. -

Code De Conduite Pour Le Water Polo

HistoFINA SWIMMING MEDALLISTS AND STATISTICS AT OLYMPIC GAMES Last updated in November, 2016 (After the Rio 2016 Olympic Games) Fédération Internationale de Natation Ch. De Bellevue 24a/24b – 1005 Lausanne – Switzerland TEL: (41-21) 310 47 10 – FAX: (41-21) 312 66 10 – E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.fina.org Copyright FINA, Lausanne 2013 In memory of Jean-Louis Meuret CONTENTS OLYMPIC GAMES Swimming – 1896-2012 Introduction 3 Olympic Games dates, sites, number of victories by National Federations (NF) and on the podiums 4 1896 – 2016 – From Athens to Rio 6 Olympic Gold Medals & Olympic Champions by Country 21 MEN’S EVENTS – Podiums and statistics 22 WOMEN’S EVENTS – Podiums and statistics 82 FINA Members and Country Codes 136 2 Introduction In the following study you will find the statistics of the swimming events at the Olympic Games held since 1896 (under the umbrella of FINA since 1912) as well as the podiums and number of medals obtained by National Federation. You will also find the standings of the first three places in all events for men and women at the Olympic Games followed by several classifications which are listed either by the number of titles or medals by swimmer or National Federation. It should be noted that these standings only have an historical aim but no sport signification because the comparison between the achievements of swimmers of different generations is always unfair for several reasons: 1. The period of time. The Olympic Games were not organised in 1916, 1940 and 1944 2. The evolution of the programme. -

EDITING for PERFORMANCE: DR JOHNSON and the STAGE I Want

Editing for performance... 75 EDITING FOR PERFORMANCE: DR JOHNSON AND THE STAGE Peter Holland Notre Dame University I want to begin by quoting one of Dr Johnson’s notes on Hamlet, a passage that, though entirely characteristic, may be less than familiar to many. Johnson is commenting on the punctuation of a passage and is concerned about a sequence of dashes towards the end of the play: To a literary friend of mine I am indebted for the following very acute observation: “Throughout this play,” says he, “there is nothing more beautiful than these dashes; by their gradual elongation, they distinctly mark the balbuciation and the increasing difficulty of utterance observable in a dying man.” To which let me add, that, although dashes are in frequent use with our tragic poets, yet they are seldom introduced with so good an effect as in the present instance. (qtd. in Wells 1: 69) Johnson’s reliance on others—and their cloaked identity—is something we are used to. So too Johnson’s yearning here both to generalize about tragic practice and to praise the particular local effect in Shakespeare can be paralleled frequently elsewhere. There is that precision that is Ilha do Desterro Florianópolis nº 49 p.075-098 jul./dez. 2005 76 Peter Holland also apparent in Johnson’s note on Ophelia’s reference to “a rope of onions”, a phrase that Pope had suggested emending to “a robe of onions”: Rope is, undoubtedly, the true reading. A rope of onions is a certain number of onions, which, for the convenience of portability, are, by the market-women, suspended from a rope: not, as the Oxford editor ingeniously, but improperly, supposes, in a bunch at the end, but by a perpendicular arrangement. -

Terry Pratchett's Discworld.” Mythlore: a Journal of J.R.R

Háskóli Íslands School of Humanities Department of English Terry Pratchett’s Discworld The Evolution of Witches and the Use of Stereotypes and Parody in Wyrd Sisters and Witches Abroad B.A. Essay Claudia Schultz Kt.: 310395-3829 Supervisor: Valgerður Guðrún Bjarkadóttir May 2020 Abstract This thesis explores Terry Pratchett’s use of parody and stereotypes in his witches’ series of the Discworld novels. It elaborates on common clichés in literature regarding the figure of the witch. Furthermore, the recent shift in the stereotypical portrayal from a maleficent being to an independent, feminist woman is addressed. Thereby Pratchett’s witches are characterized as well as compared to the Triple Goddess, meaning Maiden, Mother and Crone. Additionally, it is examined in which way Pratchett adheres to stereotypes such as for instance of the Crone as well as the reasons for this adherence. The second part of this paper explores Pratchett’s utilization of different works to create both Wyrd Sisters and Witches Abroad. One of the assessed parodies are the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm as well as the effect of this parody. In Wyrd Sisters the presence of Grimm’s fairy tales is linked predominantly to Pratchett’s portrayal of his wicked witches. Whereas the parody of “Cinderella” and the fairy tale’s trope is central to Witches Abroad. Additionally, to the Brothers Grimm’s fairy tales, Pratchett’s parody of Shakespeare’s plays is central to the paper. The focus is hereby on the tragedies of Hamlet and Macbeth, which are imitated by the witches’ novels. While Witches Abroad can solely be linked to Shakespeare due to the main protagonists, Wyrd Sisters incorporates both of the aforementioned Shakespeare plays. -

Greek Theory of Tragedy: Aristotle's Poetics

Greek Theory of Tragedy: Aristotle's Poetics The classic discussion of Greek tragedy is Aristotle's Poetics. He defines tragedy as "the imitation of an action that is serious and also as having magnitude, complete in itself." He continues, "Tragedy is a form of drama exciting the emotions of pity and fear. Its action should be single and complete, presenting a reversal of fortune, involving persons renowned and of superior attainments, and it should be written in poetry embellished with every kind of artistic expression." The writer presents "incidents arousing pity and fear, wherewith to interpret its catharsis of such of such emotions" (by catharsis, Aristotle means a purging or sweeping away of the pity and fear aroused by the tragic action). The basic difference Aristotle draws between tragedy and other genres, such as comedy and the epic, is the "tragic pleasure of pity and fear" the audience feel watching a tragedy. In order for the tragic hero to arouse these feelings in the audience, he cannot be either all good or all evil but must be someone the audience can identify with; however, if he is superior in some way(s), the tragic pleasure is intensified. His disastrous end results from a mistaken action, which in turn arises from a tragic flaw or from a tragic error in judgment. Often the tragic flaw is hubris, an excessive pride that causes the hero to ignore a divine warning or to break a moral law. It has been suggested that because the tragic hero's suffering is greater than his offense, the audience feels pity; because the audience members perceive that they could behave similarly, they feel pity. -

Garrick's Alterations of Shakespeare

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88977-3 - Shakespeare and Garrick Vanessa Cunningham Excerpt More information prologue Garrick’s alterations of Shakespeare – a note on texts The great majority of the versions of Shakespeare’s plays made by David Garrick and published during his management of Drury Lane (1747– 1776) are described on their title pages as ‘alterations’, or as having been 1 ‘alter’d for performance’. The two operas (The Fairies, 1755, and The Tempest, 1756) are said to be ‘taken from Shakespear’, while Antony and Cleopatra,publishedin1758 and generally credited jointly to Edward Capell and Garrick (though not attributed to either on the title page), is dis- tinguished from the others by its description as ‘an historical Play, written by William Shakespeare: fitted for the Stage by abridging only’. Despite the fact that Harry William Pedicord and Fredrick Louis Bergmann, modern editors of Garrick’s plays, entitle their two volumes of Shakespeare- 2 derived texts ‘adaptations’, ‘alteration’ is certainly the preferable term for discussion of Garrick’s performance versions of Shakespeare’s plays, since throughout the eighteenth century ‘alter’ was used far more commonly than ‘adapt’. Garrick, according to Pedicord and Bergmann, is believed to have been involved in the altering of some twenty-two plays by Shakespeare over the course of his professional career. In their collected edition they reproduce 3 the dozen that they consider can be authenticated. The present work discusses a selection of alterations that span Garrick’s professional career. Two are from the early years (Macbeth, Romeo and Juliet) and two from the middle period (Florizel and Perdita, Antony and Cleopatra). -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Elizabeth I and Irish Rule: Causations For

ELIZABETH I AND IRISH RULE: CAUSATIONS FOR CONTINUED SETTLEMENT ON ENGLAND’S FIRST COLONY: 1558 - 1603 By KATIE ELIZABETH SKELTON Bachelor of Arts in History Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 2009 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 2012 ELIZABETH I AND IRISH RULE: CAUSATIONS FOR CONTINUED SETTLEMENT ON ENGLAND’S FIRST COLONY: 1558 - 1603 Thesis Approved: Dr. Jason Lavery Thesis Adviser Dr. Kristen Burkholder Dr. L.G. Moses Dr. Sheryl A. Tucker Dean of the Graduate College ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 1 II. ENGLISH RULE OF IRELAND ...................................................... 17 III. ENGLAND’S ECONOMIC RELATIONSHIP WITH IRELAND ...................... 35 IV. ENGLISH ETHNIC BIAS AGAINST THE IRISH ................................... 45 V. ENGLISH FOREIGN POLICY & IRELAND ......................................... 63 VI. CONCLUSION ...................................................................... 90 BIBLIOGRAPHY ........................................................................ 94 iii LIST OF MAPS Map Page The Island of Ireland, 1450 ......................................................... 22 Plantations in Ireland, 1550 – 1610................................................ 72 Europe, 1648 ......................................................................... 75 iv LIST OF TABLES Table Page -

“From Strange to Stranger”: the Problem of Romance on the Shakespearean Stage

“From strange to stranger”: The Problem of Romance on the Shakespearean Stage by Aileen Young Liu A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English and the Designated Emphasis in Renaissance and Early Modern Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Jeffrey Knapp, Chair Professor Oliver Arnold Professor David Landreth Professor Timothy Hampton Summer 2018 “From strange to stranger”: The Problem of Romance on the Shakespearean Stage © 2018 by Aileen Young Liu 1 Abstract “From strange to stranger”: The Problem of Romance on the Shakespearean Stage by Aileen Young Liu Doctor of Philosophy in English Designated Emphasis in Renaissance and Early Modern Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Jeffrey Knapp, Chair Long scorned for their strange inconsistencies and implausibilities, Shakespeare’s romance plays have enjoyed a robust critical reconsideration in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. But in the course of reclaiming Pericles, The Winter’s Tale, Cymbeline, and The Tempest as significant works of art, this revisionary critical tradition has effaced the very qualities that make these plays so important to our understanding of Shakespeare’s career and to the development of English Renaissance drama: their belatedness and their overt strangeness. While Shakespeare’s earlier plays take pains to integrate and subsume their narrative romance sources into dramatic form, his late romance plays take exactly the opposite approach: they foreground, even exacerbate, the tension between romance and drama. Verisimilitude is a challenge endemic to theater as an embodied medium, but Shakespeare’s romance plays brazenly alert their audiences to the incredible. -

Members of Parliament Disqualified Since 1900 This Document Provides Information About Members of Parliament Who Have Been Disqu

Members of Parliament Disqualified since 1900 This document provides information about Members of Parliament who have been disqualified since 1900. It is impossible to provide an entirely exhaustive list, as in many cases, the disqualification of a Member is not directly recorded in the Journal. For example, in the case of Members being appointed 5 to an office of profit under the Crown, it has only recently become practice to record the appointment of a Member to such an office in the Journal. Prior to this, disqualification can only be inferred from the writ moved for the resulting by-election. It is possible that in some circumstances, an election could have occurred before the writ was moved, in which case there would be no record from which to infer the disqualification, however this is likely to have been a rare occurrence. This list is based on 10 the writs issued following disqualification and the reason given, such as appointments to an office of profit under the Crown; appointments to judicial office; election court rulings and expulsion. Appointment of a Member to an office of profit under the Crown in the Chiltern Hundreds or the Manor of Northstead is a device used to allow Members to resign their seats, as it is not possible to simply resign as a Member of Parliament, once elected. This is by far the most common means of 15 disqualification. There are a number of Members disqualified in the early part of the twentieth century for taking up Ministerial Office. Until the passage of the Re-Election of Ministers Act 1919, Members appointed to Ministerial Offices were disqualified and had to seek re-election.