King Philip's War by George W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

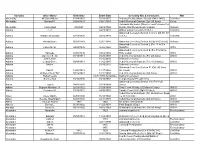

Surname Given Name Birth Date Death Date Cemetery Site & Comments

Surname Given Name Birth Date Death Date Cemetery Site & Comments. War Abernathy William Wilkins 11/24/1825 02/15/1875 Bethany Presby (Home Guard) (1861-1865) Civil War Abernathy Garland P. 03/08/1931 03/01/1984 Iredell Memorial Gardens (Cpl US Army) Korea Rehoboth Methodist (Sherrils Ford/Catawba Co) Abernathy Jimmy Edd 03/20/47 02/02/1969 Bronze Star/Purple Heart) Vietnam Vietnam Adams J. P. 04/25/1881 Willow Valley Cemetery (C.S.A.) Civil War Oakwood Cemetery Section C (Co C 4th NC Inf Adams William McLelland 07/13/1838 02/02/1918 C.S.A.) Civil War Adams Ronald Elam 06/28/1943 12/01/1988 Oakwood Cemetery Section Q (Sp 4 US Army) Vietnam Oakwood Cemetery Section L (Pvt 13 Inf Co Adams Calvin M. Sr. 04/24/1889 05/06/1968 MGOTS) WW I Oakwood Cemetery Section E (Pvt STU Army Adams Talmage 03/05/1899 09/02/1969 TNG Corps) WW I Adams Clarence E., Sr. 08/19/1911 08/20/1993 Iredell Memorial Gardens (Pvt US Army) WW II Adams John Lester 01/15/2010 Belmont Cemetery Adams Leland Orville 09/04/1914 11/02/1987 Iredell Memorial Gardens (Tec 4 US Army) WW II Adams Melvin 04/19/2012 Belmont Cemetery Oakwood Cemetery Section R (Cpl US Army Adams Paul K. 12/20/1919 11/17/1992 Air Corps) WW II Adams William Alfred "Bill" 07/26/1923 12/11/1998 Iredell Memorial Gardens (US Army) WW II Adams Robert Lewis 08/31/1991 burial date Belmont Cemetery Adams Stamey Neil 10/14/1936 10/14/1992 Temple Baptist Pfc US Army Oakwood Cemetery Section Vet (Tec4 US Adcox Floyd A. -

Conference Native Land Acknowledgement

2021 Massachusetts & Rhode Island Land Conservation Conference Land Acknowledgement It is important that we as a land conservation community acknowledge and reflect on the fact that we endeavor to conserve and steward lands that were forcibly taken from Native people. Indigenous tribes, nations, and communities were responsible stewards of the area we now call Massachusetts and Rhode Island for thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans, and Native people continue to live here and engage in land and water stewardship as they have for generations. Many non-Native people are unaware of the indigenous peoples whose traditional lands we occupy due to centuries of systematic erasure. I am participating today from the lands of the Pawtucket and Massachusett people. On the screen I’m sharing a map and alphabetical list – courtesy of Native Land Digital – of the homelands of the tribes with territories overlapping Massachusetts and Rhode Island. We encourage you to visit their website to access this searchable map to learn more about the Indigenous peoples whose land you are on. Especially in a movement that is committed to protection, stewardship and restoration of natural resources, it is critical that our actions don’t stop with mere acknowledgement. White conservationists like myself are really only just beginning to come to terms with the dispossession and exclusion from land that Black, Indigenous, and other people of color have faced for centuries. Our desire to learn more and reflect on how we can do better is the reason we chose our conference theme this year: Building a Stronger Land Movement through Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. -

The Exchange of Body Parts in the Pequot War

meanes to "A knitt them togeather": The Exchange of Body Parts in the Pequot War Andrew Lipman was IN the early seventeenth century, when New England still very new, Indians and colonists exchanged many things: furs, beads, pots, cloth, scalps, hands, and heads. The first exchanges of body parts a came during the 1637 Pequot War, punitive campaign fought by English colonists and their native allies against the Pequot people. the war and other native Throughout Mohegans, Narragansetts, peoples one gave parts of slain Pequots to their English partners. At point deliv so eries of trophies were frequent that colonists stopped keeping track of to individual parts, referring instead the "still many Pequods' heads and Most accounts of the war hands" that "came almost daily." secondary as only mention trophies in passing, seeing them just another grisly were aspect of this notoriously violent conflict.1 But these incidents a in at the Andrew Lipman is graduate student the History Department were at a University of Pennsylvania. Earlier versions of this article presented graduate student conference at the McNeil Center for Early American Studies in October 2005 and the annual conference of the South Central Society for Eighteenth-Century comments Studies in February 2006. For their and encouragement, the author thanks James H. Merrell, David Murray, Daniel K. Richter, Peter Silver, Robert Blair St. sets George, and Michael Zuckerman, along with both of conference participants and two the anonymous readers for the William and Mary Quarterly. 1 to John Winthrop, The History ofNew England from 1630 1649, ed. James 1: Savage (1825; repr., New York, 1972), 237 ("still many Pequods' heads"); John Mason, A Brief History of the Pequot War: Especially Of the memorable Taking of their Fort atMistick in Connecticut In 1637 (Boston, 1736), 17 ("came almost daily"). -

Gookin's History of the Christian Indians

AN HISTORICAL ACCOUNT OF THE DOINGS AND SUFFERINGS OF THE CHRISTIAN INDIANS IN NEW ENGLAND, IN THE YEARS 1675, 1676, 1677 IMPARTIALLY DRAWN BY ONE WELL ACQUAINTED WITH THAT AFFAIR, A ND PRESENTED UNTO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE THE CORPORATION RESIDING IN LONDON, APPOINTED BY THE KING'S MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY FOR PROMOTING THE GOSPEL AMONG THE INDIANS IN AMERICA. PRELIMINARY NOTICE. IN preparing the following brief sketch of the principal incidents in the life of the author of “The History of the Christian Indians,” the Publishing Committee have consulted the original authorities cited by the -American biographical writers, and such other sources of information as were known to them, for the purpose of insuring greater accuracy; but the account is almost wholly confined to the period of his residence in New England, and is necessarily given in the most concise manner. They trust, that more ample justice will yet be done to his memory by the biographer and the historian. DANIEL GOOKIN was born in England, about A. D. 1612. As he is termed “a Kentish soldier” by one of his contemporaries, who was himself from the County of Kent, 1 it has been inferred, with good reason, that Gookin was a native of that county. In what year he emigrated to America, does not clearly appear; but he is supposed to have first settled in the southern colony of Virginia, from whence he removed to New England. Cotton Mather, in his memoir of Thompson, a nonconformist divine of Virginia, has the following quaint allusion to our author “A constellation of great converts there Shone round him, and his heavenly glory were. -

Winslows: Pilgrims, Patrons, and Portraits

Copyright, The President and Trustees of Bowdoin College Brunswick, Maine 1974 PILGRIMS, PATRONS AND PORTRAITS A joint exhibition at Bowdoin College Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Organized by Bowdoin College Museum of Art Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/winslowspilgrimsOObowd Introduction Boston has patronized many painters. One of the earhest was Augustine Clemens, who began painting in Reading, England, in 1623. He came to Boston in 1638 and probably did the portrait of Dr. John Clarke, now at Harvard Medical School, about 1664.' His son, Samuel, was a member of the next generation of Boston painters which also included John Foster and Thomas Smith. Foster, a Harvard graduate and printer, may have painted the portraits of John Davenport, John Wheelwright and Increase Mather. Smith was commis- sioned to paint the President of Harvard in 1683.^ While this portrait has been lost, Smith's own self-portrait is still extant. When the eighteenth century opened, a substantial number of pictures were painted in Boston. The artists of this period practiced a more academic style and show foreign training but very few are recorded by name. Perhaps various English artists traveled here, painted for a time and returned without leaving a written record of their trips. These artists are known only by their pictures and their identity is defined by the names of the sitters. Two of the most notable in Boston are the Pierpont Limner and the Pollard Limner. These paint- ers worked at the same time the so-called Patroon painters of New York flourished. -

MASSACHUSETTS: Or the First Planters of New-England, the End and Manner of Their Coming Thither, and Abode There: in Several EPISTLES (1696)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Joshua Scottow Papers Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 1696 MASSACHUSETTS: or The first Planters of New-England, The End and Manner of their coming thither, and Abode there: In several EPISTLES (1696) John Winthrop Governor, Massachusetts Bay Colony Thomas Dudley Deputy Governor, Massachusetts Bay Colony John Allin Minister, Dedham, Massachusetts Thomas Shepard Minister, Cambridge, Massachusetts John Cotton Teaching Elder, Church of Boston, Massachusetts See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/scottow Part of the American Studies Commons Winthrop, John; Dudley, Thomas; Allin, John; Shepard, Thomas; Cotton, John; Scottow, Joshua; and Royster,, Paul Editor of the Online Electronic Edition, "MASSACHUSETTS: or The first Planters of New- England, The End and Manner of their coming thither, and Abode there: In several EPISTLES (1696)" (1696). Joshua Scottow Papers. 7. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/scottow/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Joshua Scottow Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors John Winthrop; Thomas Dudley; John Allin; Thomas Shepard; John Cotton; Joshua Scottow; and Paul Royster, Editor of the Online Electronic Edition This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ scottow/7 ABSTRACT CONTENTS In 1696 there appeared in Boston an anonymous 16mo volume of 56 pages containing four “epistles,” written from 66 to 50 years earlier, illustrating the early history of the colony of Massachusetts Bay. -

BIRTH of BOSTON PURITANS CREATE “CITY UPON a HILL” by Our Newssheet Writer in Boston September 8, 1630

BIRTH OF BOSTON PURITANS CREATE “CITY UPON A HILL” By our newssheet writer in Boston September 8, 1630 URITAN elders declared yesterday that the Shawmut Peninsula will be called P“Boston” in the future. The seat of government of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, which began two years ago, will also be in Boston. It follows a meeting between John Winthrop, the colony’s elected governor and clergyman William Blackstone, one of the first settlers to live in Trimount on the peninsula, so called because of its three “mountains.” Blackstone recommended its spring waters. Winthrop (pictured) left England earlier this year to lead ships across the Atlantic. Of the hundreds of passengers on board, many were Puritans seeking religious freedom, eager to start a new life in New England. They had prepared well, bringing many horses and cows with them. The new governor, a member of the English upper classes, brought the royal charter of the Massachusetts Bay Company with him. However, the company’s charter did not impose control from England—the colony would be effectively self-governing. Arriving in Cape Ann, the passengers went ashore and picked fresh strawberries—a welcome change from shipboard life! Colonists had previously settled in the area, but dwellings had been abandoned after many had died in drastically reduced by disease. But Winthrop the harsh winter or were starving. is taking few chances by spreading out One early colonist was Roger Conant, who settlements to make it difficult for potentially established Salem near the Native Naumkeag hostile groups to attack. people. But Winthrop and the other Puritan In time, Winthrop believes many more leaders chose not to settle there, but to continue Puritans will flock to his “City upon a Hill” to the search for their own Promised Land. -

Southern Medical and Surgical Journal

SOUTHERN MEDICAL AND SURGICAL JOURNAL. EDITED BY HENRY F. CAMPBELL, A.M., M. D., GEORGIA PROKES-OR OK BPECIAL AND COMPARATIVE ANATOMY IN TBI MEDICAL COLLEGK OF ROBERT CAMPBELL, A.M..M.D., DBMOSrtTRATOB OF ANATOMY IN THE MEDICAL COLLEGE MEPICAL COLLEGE OF GEORGIA. YOL. XIV.—1858.—NEW SERIES. AUGUSTA, G A: J. MORRIS, PRINTER AND PUBLISHER. 1858. SOUTHERN MEDICAL KM) SURGICAL JOURNAL. (NEW SERIES.) Vol. XIV.] AUGUSTA, GEORGIA, OCTOBER, 1838. [No. 10. ORIGINAL AXD ECLECTIC. ARTICLE XXII. Observations on Malarial Fever. By Joseph Joxes, A.M., M.D., Professor of Physics and Natural Theology in the University of Georgia, Athens; Professor of Chemistry and Pharmacy in the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta; formerly Professor of Medical Chemistry in the Medical College of Savannah. [Continued from page 601 of September Xo. 1858.] Case XXVIII.—Scotch seaman ; age 14 ; light hair, blue eyes, florid complexion; height 5 feet 2 inches; weight 95 lbs. From light ship, lying at the mouth of Savannah river. Was taken sick three days ago. September 16th, 7 o'clock P. M. Face as red as scarlet; skin in a profuse perspiration, which has saturated his thick flannel shirt and wet the bed-clothes. Pulse 100. Eespiration 24 : does not correspond with the flushed appearance of his face. Tem- perature of atmosphere, 88° F. ; temp, of hand, 102 ; temp, un- der tongue, 103.25. Tip and middle of tongue clean and of a bright red color; posterior portion (root) of tongue, coated with yellow fur; tongue rough and perfectly dry. When the finger is passed over the tongue, it feels as dry and harsh as a rough board. -

1835. EXECUTIVE. *L POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT

1835. EXECUTIVE. *l POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT. Persons employed in the General Post Office, with the annual compensation of each. Where Compen Names. Offices. Born. sation. Dol. cts. Amos Kendall..., Postmaster General.... Mass. 6000 00 Charles K. Gardner Ass't P. M. Gen. 1st Div. N. Jersey250 0 00 SelahR. Hobbie.. Ass't P. M. Gen. 2d Div. N. York. 2500 00 P. S. Loughborough Chief Clerk Kentucky 1700 00 Robert Johnson. ., Accountant, 3d Division Penn 1400 00 CLERKS. Thomas B. Dyer... Principal Book Keeper Maryland 1400 00 Joseph W. Hand... Solicitor Conn 1400 00 John Suter Principal Pay Clerk. Maryland 1400 00 John McLeod Register's Office Scotland. 1200 00 William G. Eliot.. .Chie f Examiner Mass 1200 00 Michael T. Simpson Sup't Dead Letter OfficePen n 1200 00 David Saunders Chief Register Virginia.. 1200 00 Arthur Nelson Principal Clerk, N. Div.Marylan d 1200 00 Richard Dement Second Book Keeper.. do.. 1200 00 Josiah F.Caldwell.. Register's Office N. Jersey 1200 00 George L. Douglass Principal Clerk, S. Div.Kentucky -1200 00 Nicholas Tastet Bank Accountant Spain. 1200 00 Thomas Arbuckle.. Register's Office Ireland 1100 00 Samuel Fitzhugh.., do Maryland 1000 00 Wm. C,Lipscomb. do : for) Virginia. 1000 00 Thos. B. Addison. f Record Clerk con-> Maryland 1000 00 < routes and v....) Matthias Ross f. tracts, N. Div, N. Jersey1000 00 David Koones Dead Letter Office Maryland 1000 00 Presley Simpson... Examiner's Office Virginia- 1000 00 Grafton D. Hanson. Solicitor's Office.. Maryland 1000 00 Walter D. Addison. Recorder, Div. of Acc'ts do.. -

"In the Pilgrim Way" by Linda Ashley, A

In the Pilgrim Way The First Congregational Church, Marshfield, Massachusetts 1640-2000 Linda Ramsey Ashley Marshfield, Massachusetts 2001 BIBLIO-tec Cataloging in Publication Ashley, Linda Ramsey [1941-] In the pilgrim way: history of the First Congregational Church, Marshfield, MA. Bibliography Includes index. 1. Marshfield, Massachusetts – history – churches. I. Ashley, Linda R. F74. 2001 974.44 Manufactured in the United States. First Edition. © Linda R. Ashley, Marshfield, MA 2001 Printing and binding by Powderhorn Press, Plymouth, MA ii Table of Contents The 1600’s 1 Plimoth Colony 3 Establishment of Green’s Harbor 4 Establishment of First Parish Church 5 Ministry of Richard Blinman 8 Ministry of Edward Bulkley 10 Ministry of Samuel Arnold 14 Ministry of Edward Tompson 20 The 1700’s 27 Ministry of James Gardner 27 Ministry of Samuel Hill 29 Ministry of Joseph Green 31 Ministry of Thomas Brown 34 Ministry of William Shaw 37 The 1800’s 43 Ministry of Martin Parris 43 Ministry of Seneca White 46 Ministry of Ebenezer Alden 54 Ministry of Richard Whidden 61 Ministry of Isaac Prior 63 Ministry of Frederic Manning 64 The 1900’s 67 Ministry of Burton Lucas 67 Ministry of Daniel Gross 68 Ministry of Charles Peck 69 Ministry of Walter Squires 71 Ministry of J. Sherman Gove 72 Ministry of George W. Zartman 73 Ministry of William L. Halladay 74 Ministry of J. Stanley Bellinger 75 Ministry of Edwin C. Field 76 Ministry of George D. Hallowell 77 Ministry of Vaughn Shedd 82 Ministry of William J. Cox 85 Ministry of Robert H. Jackson 87 Other Topics Colonial Churches of New England 92 United Church of Christ 93 Church Buildings or Meetinghouses 96 The Parsonages 114 Organizations 123 Sunday School and Youth 129 Music 134 Current Officers, Board, & Committees 139 Gifts to the Church 141 Memorial Funds 143 iii The Centuries The centuries look down from snowy heights Upon the plains below, While man looks upward toward those beacon lights Of long ago. -

(King Philip's War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial

Connecticut Unscathed: Victory in The Great Narragansett War (King Philip’s War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Major Jason W. Warren, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin Jr., Advisor Alan Gallay, Kristen Gremillion Peter Mansoor, Geoffrey Parker Copyright by Jason W. Warren 2011 Abstract King Philip’s War (1675-1676) was one of the bloodiest per capita in American history. Although hostile native groups damaged much of New England, Connecticut emerged unscathed from the conflict. Connecticut’s role has been obscured by historians’ focus on the disasters in the other colonies as well as a misplaced emphasis on “King Philip,” a chief sachem of the Wampanoag groups. Although Philip formed the initial hostile coalition and served as an important leader, he was later overshadowed by other sachems of stronger native groups such as the Narragansetts. Viewing the conflict through the lens of a ‘Great Narragansett War’ brings Connecticut’s role more clearly into focus, and indeed enables a more accurate narrative for the conflict. Connecticut achieved success where other colonies failed by establishing a policy of moderation towards the native groups living within its borders. This relationship set the stage for successful military operations. Local native groups, whether allied or neutral did not assist hostile Indians, denying them the critical intelligence necessary to coordinate attacks on Connecticut towns. The English colonists convinced allied Mohegan, Pequot, and Western Niantic warriors to support their military operations, giving Connecticut forces a decisive advantage in the field. -

The Legacies of King Philip's War in the Massachusetts Bay Colony

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1987 The legacies of King Philip's War in the Massachusetts Bay Colony Michael J. Puglisi College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Puglisi, Michael J., "The legacies of King Philip's War in the Massachusetts Bay Colony" (1987). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623769. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-f5eh-p644 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: • Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. • Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is also filmed as one exposure and is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or as a 17”x 23” black and white photographic print.