Danilo Dolci and the Case of Partinico 1955-19781 Peter Jones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orario Autolinea Extraurbana: Altavilla - Termini Imerese Stazione FS (696)

Allegato "C" Assessorato Regionale delle Infrastrutture e della Mobilità - Dipartimento delle Infrastrutture, della Mobilità e dei Trasporti Servizio 1 "Autotrasporto Persone" Contratto di Affidamento Provvisorio dei servizi Extraurbani di T.P.L. in autobus già in concessione regionale Impresa: Azienda Siciliana Trasporti - A.S.T. S.p.A. Codice 64 Orario Autolinea Extraurbana: Altavilla - Termini Imerese Stazione FS (696) C O R S E C O R S E 1A 4A 2A 3A 1R 2R 3R 5R KM STAZIONAMENTI KM FERIALE FERIALE FERIALE FERIALE FERIALE FERIALE FERIALE FERIALE SCOLASTICA SCOLASTICA SCOLASTICA SCOLASTICA 7.10 0,0 Capolinea 18,7 9.25 14.55 Altavilla - via Loreto 7.25 10.15 12.45 I Fermata intermedia 10,5 9.10 10.10 12.40 14.40 S.Nicola l'Arena - corso Umberto 7.35 7.50 10.25 12.55 I Fermata intermedia 6,2 9.00 10.00 12.30 14.30 Trabia - via la Masa 8.05 8.20 10.55 13.25 18,7 Capolinea 0 8.30 9.30 12.00 14.00 Termini I. - Scalo F.S. Prescrizioni d'Esercizio Divieto di servizio locale fra Termini Alta-Termini stazione f.s. e viceversa. Allegato "C" Assessorato Regionale delle Infrastrutture e della Mobilità - Dipartimento delle Infrastrutture, della Mobilità e dei Trasporti Servizio 1 "Autotrasporto Persone" Contratto di Affidamento Provvisorio dei servizi Extraurbani di T.P.L. in autobus già in concessione regionale Impresa: Azienda Siciliana Trasporti - A.S.T. S.p.A. Codice 64 Orario Autolinea Extraurbana: BAGHERIA - ALTAVILLA (cod. 722) C O R S E C O R S E 1A 6A 2A 7A 3A 8A 9A 4A 5A 1R 10R 8R 7R 2R 11R 9R 3R 6R 4R 5R KM KM feriale feriale feriale feriale -

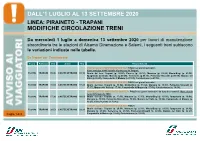

Dall'1 Luglio Al 13 Settembre 2020 Modifiche Circolazione

DALL’1 LUGLIO AL 13 SETTEMBRE 2020 LINEA: PIRAINETO - TRAPANI MODIFICHE CIRCOLAZIONE TRENI Da mercoledì 1 luglio a domenica 13 settembre 2020 per lavori di manutenzione straordinaria tra le stazioni di Alcamo Diramazione e Salemi, i seguenti treni subiscono le variazioni indicate nelle tabelle. Da Trapani per Castelvetrano Treno Partenza Ora Arrivo Ora Provvedimenti CANCELLATO E SOSTITUITO CON BUS PA202 nei giorni lavorativi. Il bus anticipa di 40’ l’orario di partenza da Trapani. R 26622 TRAPANI 05:46 CASTELVETRANO 07:18 Orario del bus: Trapani (p. 05:06), Paceco (p. 05.16), Marausa (p. 05:29) Mozia-Birgi (p. 05.36), Spagnuola (p.05:45), Marsala (p.05:59), Terrenove (p.06.11), Petrosino-Strasatti (p.06:19), Mazara del Vallo (p.06:40), Campobello di Mazara (p.07:01), Castelvetrano (a.07:18). CANCELLATO E SOSTITUITO CON BUS PA218 nei giorni lavorativi. R 26640 TRAPANI 16:04 CASTELVETRANO 17:24 Orario del bus: Trapani (p. 16:04), Mozia-Birgi (p. 16:34), Marsala (p. 16:57), Petrosino-Strasatti (p. 17:17), Mazara del Vallo (p. 17:38), Campobello di Mazara (p. 17:59), Castelvetrano (a. 18:16). CANCELLATO E SOSTITUITO CON BUS PA220 nei giorni lavorativi da lunedì a venerdì. Non circola venerdì 14 agosto 2020. R 26642 TRAPANI 17:30 CASTELVETRANO 18:53 Orario del bus: Trapani (p. 17:30), Marausa (p. 17:53), Mozia-Birgi (p. 18:00), Spagnuola (p. 18:09), Marsala (p. 18:23), Petrosino-Strasatti (p. 18:43), Mazara del Vallo (p. 19:04), Campobello di Mazara (p. 19:25), Castelvetrano (a. 19:42). -

IO SONO STATO a CORLEONE Texto Y Fotos Miquel Silvestre La Silueta De Una Costa Abrupta Se Recorta En El Atardecer

12 PALERMO IO SONO STATO A CORLEONE Texto y fotos Miquel Silvestre La silueta de una costa abrupta se recorta en el atardecer. Destaca el gran cono truncado del Etna. Casi es de noche sobre el Estrecho de Messina, vía marítima a un territorio de alborotada historia, arraigadas costumbres e inquebrantables códigos de honor. No soy del todo extranjero. Hasta bien mediado el XIX, Sicilia fue España desde que en 1282 quedó bajo dominio del aragonés Pedro el Grande. La lengua sicilia- na mezcla latín, italiano, berebere, castellano y catalán. El nombre del pueblo de Barcellona recuerda ese legado. Como aquellos jóvenes influidos por Goethe que recorrían Europa durante el Siglo de las Luces, yo sigo mi periplo motociclista en este extremo del Mediterráneo hecho de lava y de sangre. Palermo huele a sal y a pescado asado. La ciudad vive de cara al mar. El monumental casco antiguo goza de la decadencia más bella que haya visto antes. Callejones, humedad y revueltas. Tras la monu- mental Porta Felice aparece un sinuoso y barroco laberinto urbano con sorpresas escondidas tras cada recodo. En una plazoleta encuentro una chica armada de un bote de pintura en spray. Está tachando el 13 “Beatrice ti amo” rubricado en la pared. The abrupt coastline forms a stark silhouette against the sunset. Mount Etna Italia está llena de estas declaraciones stands out; a cone shape, flattened off at the top. It is almost night-time on the de amor escritas en muros, quitamiedos Strait of Messina, the sea route to a land with an eventful history, deep-rooted o sábanas extendidas. -

Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism

Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism Sophus A. Reinert Robert Fredona Working Paper 18-021 Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism Sophus A. Reinert Harvard Business School Robert Fredona Harvard Business School Working Paper 18-021 Copyright © 2017 by Sophus A. Reinert and Robert Fredona Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism Sophus A. Reinert and Robert Fredona ABSTRACT: N.S.B. Gras, the father of Business History in the United States, argued that the era of mercantile capitalism was defined by the figure of the “sedentary merchant,” who managed his business from home, using correspondence and intermediaries, in contrast to the earlier “traveling merchant,” who accompanied his own goods to trade fairs. Taking this concept as its point of departure, this essay focuses on the predominantly Italian merchants who controlled the long‐distance East‐West trade of the Mediterranean during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Until the opening of the Atlantic trade, the Mediterranean was Europe’s most important commercial zone and its trade enriched European civilization and its merchants developed the most important premodern mercantile innovations, from maritime insurance contracts and partnership agreements to the bill of exchange and double‐entry bookkeeping. Emerging from literate and numerate cultures, these merchants left behind an abundance of records that allows us to understand how their companies, especially the largest of them, were organized and managed. -

Ecovillaggi: Esperienze Comunitarie Tra Utopia E Realtà

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Archive - Università di Pisa UNIVERSITÀ DI PISA DIPARTIMENTO DI SCIENZE POLITICHE E SOCIALI CORSO DI DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN STORIA E SOCIOLOGIA DELLA MODERNITÀ Ecovillaggi: esperienze comunitarie tra utopia e realtà CANDIDATA Rossana Guidi TUTOR Prof. Mario Aldo Toscano Ciclo 2007-2009 1 L’utopia del futuro costruisce il presente. (Prigogine) 2 Indice: Introduzione…………………………………………………… p. 5. Parte I: Industrializzazione, capitalismo, modernità………...p. 12. 1.1 Nascita della società capitalistica moderna………………...p. 13. Parte II: Le avventure intellettuali e pratiche della comunità. ……………………………………………………………………p. 26. 2.2.1 Dissoluzione e resistenze della comunità………………... p. 26. 2.2.2 Tracce di comunità……………………………………..... p. 36. 2.2.3 Dalla comunità alla società: il pensiero degli autori classici della sociologia…………………………………..p. 41. Parte III: Il pensiero utopico e le sue realizzazioni……………p. 57 3.1 Socialisti utopisti……………………………………………..p. 57. 3.2 Comunitarismo americano…………………………………...p. 69. 3.3 Movimento Hippy……………………………………………p. 82. 3.4 Sviluppo sostenibile e nascita degli ecovillaggi…………….p. 86. Parte IV: Fenomenologia e geopolitica dell’ecovillaggio……p. 100. 4.1 Definizione di ecovillaggio…………………………… p. 100. 4.2 Ecovillaggi a confronto………………………………... p. 110. 4.2.1 Il metodo decisionale…………………………………...p. 113. 4.3.2 Organizzazione economica……………………………..p. 124. 4.3.3 Accorgimenti ecologici………………………………..p. 130. 3 4.3.4 Orientamento religioso………………………………...p. 138. 4.4 Ecovillaggi: tra utopia e realtà………………………....p. 140. 4.5 Contenuto razionalistico degli ecovillaggi…………….p. 151. 4.6 Breve quadro concettuale sulla disuguaglianza sociale..p. 168. Parte V: Punto applicativo e descrizione di un caso specifico: la comune di Bagnaia……………………………………….……p. -

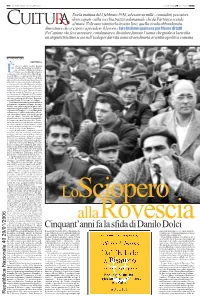

Cinquant'anni Fa La Sfida Di Danilo Dolci

40 LA DOMENICA DI REPUBBLICA DOMENICA 29 GENNAIO 2006 Era la mattina del 2 febbraio 1956, ed erano in mille - contadini, pescatori, disoccupati - sulla vecchia trazzera demaniale che da Partinico scende al mare. Volevano rimetterla in sesto loro, quella strada abbandonata, dimostrare che ci si poteva prendere il lavoro e fare insieme qualcosa per il bene di tutti. Fu l’azione che fece arrestare, condannare e diventare famoso l’uomo che guidava la rivolta: un utopista triestino sceso nell’isola per dar vita a una straordinaria avventura politica e umana ATTILIO BOLZONI PARTINICO ancora senza nome questa strada che dal paese scende fi- no al mare. Ripida nel primo Ètratto, poi va giù dolcemente con le sue curve che sfiorano alberi di pe- sco e di albicocco, passa sotto due ponti, scavalca la ferrovia. L’hanno asfaltata appena una decina di anni fa, prima era un sentiero, una delle tante regie trazze- re borboniche che attraversano la cam- pagna siciliana. È lunga otto chilometri, un giorno forse la chiameranno via dello Sciopero alla Rovescia. Siamo sul ciglio di questa strada di Partinico mezzo se- colo dopo quel 2 febbraio del ‘56, la stia- mo percorrendo sulle tracce di un uomo che sapeva inventare il futuro. Era un ir- regolare Danilo Dolci, uno di confine. Quella mattina erano quasi in mille qui sul sentiero e in mezzo al fango, inverno freddo, era caduta anche la neve sullo spuntone tagliente dello Jato. I pescatori venivano da Trappeto e i contadini dalle valli intorno, c’erano sindacalisti, alleva- tori, tanti disoccupati. E in fondo quegli altri, gli «sbirri» mandati da Palermo, pronti a caricare e a portarseli via quelli lì. -

Prato and Montemurlo Tuscany That Points to the Future

Prato Area Prato and Montemurlo Tuscany that points to the future www.pratoturismo.it ENG Prato and Montemurlo Prato and Montemurlo one after discover treasures of the Etruscan the other, lying on a teeming and era, passing through the Middle busy plain, surrounded by moun- Ages and reaching the contempo- tains and hills in the heart of Tu- rary age. Their geographical posi- scany, united by a common destiny tion is strategic for visiting a large that has made them famous wor- part of Tuscany; a few kilometers ldwide for the production of pre- away you can find Unesco heritage cious and innovative fabrics, offer sites (the two Medici Villas of Pog- historical, artistic and landscape gio a Caiano and Artimino), pro- attractions of great importance. tected areas and cities of art among Going to these territories means the most famous in the world, such making a real journey through as Florence, Lucca, Pisa and Siena. time, through artistic itineraries to 2 3 Prato contemporary city between tradition and innovation PRATO CONTEMPORARY CITY BETWEEN TRADITION AND INNOVATION t is the second city in combination is in two highly repre- Tuscany and the third in sentative museums of the city: the central Italy for number Textile Museum and the Luigi Pec- of inhabitants, it is a ci Center for Contemporary Art. The contemporary city ca- city has written its history on the art pable of combining tradition and in- of reuse, wool regenerated from rags novation in a synthesis that is always has produced wealth, style, fashion; at the forefront, it is a real open-air the art of reuse has entered its DNA laboratory. -

Tv Shows, Feature Films & Documentaries

TV SHOWS, FEATURE FILMS & DOCUMENTARIES TITLES AVAILABLE DUBBED AND SUBTITLED IN SPANISH. INDEX INDEX TITLES AVAILABLE DUBBED ...And It’s Snowing Outside! 6 Grand Torino (The) 27 Storm (The) 14 Angel Of Sarajevo (The) 6 Hidden Vatican (The) 7 Terra Sancta: Guardians Of Salvation’s Source 25 Assault (The) 10 Imperium: Nero 19 Third Secret Of Fatima (The) 27 Bartali, The Iron Man 16 Imperium: Pompeii 19 Third Truth (The) 28 Borsellino, The 57 Days 12 Imperium: Saint Augustine 20 Turin’s Butterfly 11 Boss In The Kitchen (A) 9 Imperium: Saint Peter 20 Wannabe Widowed 12 Bright Flight 13 Lady Of The Camellias 21 Caravaggio 16 Long Lasting Youth 21 Claire & Francis 17 Maria Goretti 28 Countess Of Castiglione (The) 25 Marriage (A) 8 Curfew - Don Pappagallo (The) 26 Mearshes Intrique (The) 22 Displaced Child (The) 11 My House Is Full Of Mirrors 15 Don Zeno 17 Oro Di Scampia (L’) 7 Fear Of Loving 1, 2 9 Over The Shop 13 Francesco 22 Pompeii, Stories From An Eruption 23 Frederick Barbarossa 15 Resurrection 23 Giovanni Falcone, The Judge 18 Saint Bakhita 24 Girls Of San Frediano (The) 26 Scent Of Love 14 Giuseppe Moscati, 18 Song’e Napule 10 Good Season (A) 8 Star Of Bethlehem 24 Credits not contractual Credits INDEX TITLES AVAILABLE SUBTITLED Anija 36 Lonely Hero (A) 42 Away From Me 33 Smile Of The Leader (The) 35 Balancing Act (The) 37 Song’e Napule 34 Black Souls 31 Triplet (The) 39 Caesar Must Die 36 Viva La Libertà 35 Cardboard Village (The) 40 Chair Of Happiness (The) 34 Darker Than Midnight 31 Dinner (The) 32 Easy 40 Entrepreneur (The) 41 -

DISP. II GRADO PER GAE.Pdf

Disponibilità Disponibilità Residue su Residue su Cattedre Cattedre PR Codice Scuola Denominazione Scuola Denominazione Comune CDC Interne Esterne Completamento cattedre esterne PA PAIS01600G IS "MAJORANA" PALERMO A010 1 0 PA PAIS01400X DON CALOGERO DI VINCENTI BISACQUINO A011 1 1 12+6 DON COLLETTO CORLEONE PAIS00900C PA PAIS01700B "G. SALERNO" GANGI A011 1 0 PA PAIS018007 I.I.S. P. DOMINA PETRALIA SOTTANA PETRALIA SOTTANA A011 1 0 PA PAPS16000X I.C. DI II GRADO "SAVERIA PROFETA" USTICA A011 1 0 PA PAIS00900C IS DON G. COLLETTO CORLEONE A013 1 0 PA PAIS01100C I.I.S.S. LERCARA FRIDDI LERCARA FRIDDI A013 2 0 PA PAIS01100C I.I.S.S. LERCARA FRIDDI LERCARA FRIDDI A018 0 1 12+6 DON CALOGERO DI VINCENTI BISACQUINO PAIS01400X PA PAIS01700B "G. SALERNO" GANGI A018 1 0 PA PAIS00900C IS DON G. COLLETTO CORLEONE A019 0 1 14+4 DON CALOGERO DI VINCENTI BISACQUINO PAIS01400X PA PAIS01100C I.I.S.S. LERCARA FRIDDI LERCARA FRIDDI A019 2 0 PA PAIS039008 I.I.S. G. D'ALESSANDRO BAGHERIA A019 2 1 9+9 SCADUTO BAGHERIA PAPC01000V PA PAIS004009 UGO MURSIA CARINI A021 0 1 12+6 ABRUZZI - GRASSI PAIS02900N PA PARI010007 S.D'ACQUISTO BAGHERIA BAGHERIA A026 0 1 15+3 FERRARA PAIS02300P PA PARI02802E IPIA SEZ. CAR.PAGLIARELLI ASCIONE PALERMO A026 0 1 13+6 PIAZZA PARH02050Q PA PATF03050P I.T.I.V.E.III SERALE PALERMO A026 0 1 15+4 CASCINO PARH050006 PA PAIS021003 ISTITUTO SUPERIORE DANILO DOLCI PARTINICO A031 1 0 PA PAIS01600G IS "MAJORANA" PALERMO A037 1 0 PA PAIS02200V JACOPO DEL DUCA - DIEGO BIANCA AMATO CEFALU' A037 0 1 16+2 GIOENI TRABIA PAIS03600R PA PAIS01100C I.I.S.S. -

Società E Cultura 65

Società e Cultura Collana promossa dalla Fondazione di studi storici “Filippo Turati” diretta da Maurizio Degl’Innocenti 65 1 Manica.indd 1 19-11-2010 12:16:48 2 Manica.indd 2 19-11-2010 12:16:48 Giustina Manica 3 Manica.indd 3 19-11-2010 12:16:53 Questo volume è stato pubblicato grazie al contributo di fondi di ricerca del Dipartimento di studi sullo stato dell’Università de- gli Studi di Firenze. © Piero Lacaita Editore - Manduria-Bari-Roma - 2010 Sede legale: Manduria - Vico degli Albanesi, 4 - Tel.-Fax 099/9711124 www.lacaita.com - [email protected] 4 Manica.indd 4 19-11-2010 12:16:54 La mafia non è affatto invincibile; è un fatto uma- no e come tutti i fatti umani ha un inizio e avrà anche una fine. Piuttosto, bisogna rendersi conto che è un fe- nomeno terribilmente serio e molto grave; e che si può vincere non pretendendo l’eroismo da inermi cittadini, ma impegnando in questa battaglia tutte le forze mi- gliori delle istituzioni. Giovanni Falcone La lotta alla mafia deve essere innanzitutto un mo- vimento culturale che abitui tutti a sentire la bellezza del fresco profumo della libertà che si oppone al puzzo del compromesso, dell’indifferenza, della contiguità e quindi della complicità… Paolo Borsellino 5 Manica.indd 5 19-11-2010 12:16:54 6 Manica.indd 6 19-11-2010 12:16:54 Alla mia famiglia 7 Manica.indd 7 19-11-2010 12:16:54 Leggenda Archivio centrale dello stato: Acs Archivio di stato di Palermo: Asp Public record office, Foreign office: Pro, Fo Gabinetto prefettura: Gab. -

Recycled Wool in Prato, Italy: Between History and Modernity

2018 Textile Sustainability Conference | Texcursion | Updated April 27, 2018 Recycled Wool in Prato, Italy: Between History and Modernity Hosts: Confindustria Toscana Nord and ICEA Location: Prato, Italy: Tuscany Region When: Thursday, October 25, 2018 COST: $50 USD Travel: Milano Centrale train station to Florence, Italy and then local train to Prato porta al Serraglio Station. Attendee is responsible for arriving/departing to/from Milano Centrale train station on their own. This cost is NOT included. ARRIVAL: The tour begins at 11am. Recommended departure times from Milano Centrale could be at 7:20am (arrival at Prato at 09:29am) or 8:20am (arrival at 10:41am). DEPARTURE: Return to Milano Centrale by taking the 17:42 train from Prato to Florence and then arrive at Milano Centrale at 20:29 Included costs: Transport around Prato, lunch, entrance at the Textile Museum of Prato Maximum attendees: 30 Agenda (subject to change): 11:00am: Museo del Tessuto, which is at 10-minutes by walk from Prato porta al Serraglio Station. A representative from Condindustria Toscana Nord will be at the train station and will walk with you to the Museo del Tessuto. - Welcome meeting and presentation of Prato industrial cluster and of the specificities of carded (recycled) wool industry - Visit of the museum - Light lunch served in the Museo venues - After Lunch: (13:30 – 17:00) Visit of 2 companies specialised in different processes that will offer a comprehensive overview of all the manufacturing processes related to carded (recycled) wool Return to Milano Centrale by taking the 17:42 train from Prato to Florence and then arrive at Milano Centrale at 20:29 Additional Information about tour and hosts: Museo Del Tessuto Di Prato ( http://www.museodeltessuto.it/?lang=en ) The Museum was founded in 1975 within the "Tullio Buzzi" Industrial Technical Textile Institute, as the result of an initial donation of approximately 600 historical textile fragments. -

Aldo Capitini on Opposition and Liberation

Aldo Capitini on Opposition and Liberation Aldo Capitini on Opposition and Liberation: A Life in Nonviolence Edited by Piergiorgio Giacchè Translated by Jodi L. Sandford Aldo Capitini on Opposition and Liberation: A Life in Nonviolence Edited by Piergiorgio Giacchè Translated by Jodi L. Sandford This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Piergiorgio Giacchè and Jodi L. Sandford All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-4846-5 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-4846-6 This book is dedicated to all people who have furthered the concept of inclusion, peace, and nonviolence; opposing fascism, prevarication, and prejudice of any sort. TABLE OF CONTENTS Premise ...................................................................................................... ix Giuseppe Moscati Introductory Note to the Translation ......................................................... xi Jodi L. Sandford Translation Once Again with Capitini ........................................................................... 2 Goffredo Fofi Introduction ...............................................................................................