Water Harvesting for Peacebuilding in South Sudan Acronyms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cholera in South Sudan Situation Report # 95 As at 23:59 Hours, 29 September to 5 October 2014

Republic of South Sudan Cholera in South Sudan Situation Report # 95 as at 23:59 Hours, 29 September to 5 October 2014 Situation Update As of 5 October 2014, a total of 6,139 cholera cases including 139 deaths (CFR 2%) had been reportedTable 1. Summary in South of Suda choleran as cases summarizedreported in in Juba Tables County 1 and, 23 2.April – 5 October 2014 New New New deaths Total cases Total Total admisions discharges Total Total cases Reporting Sites 29 Sept to currently facility community Total cases 29 Sept to 29 Sept to deaths discharged 5 Oct 2014 admitted deaths deaths 5 Oct 2014 5 Oct 2014 JTH CTC 0 0 0 0 16 0 16 1466 1482 Gurei CTC (changed to ORP) Closed 28 July 2 0 2 365 367 Tongping CTC 0 2 1 3 69 72 Closed August Jube 3/UN House CTC Closed August 0 0 0 0 97 97 Nyakuron West CTC Closed 15 July 0 0 0 18 18 Gumbo CTC Closed 5 July 0 0 0 48 48 Nyakuron ORP Closed 5 July 0 0 0 20 20 Munuki ORP Closed 5 July 0 0 0 8 8 Gumbo ORP Closed 15 July 0 3 3 67 70 Pager PHCU 0 0 0 0 1 5 6 42 48 Other sites 0 0 0 1 15 16 1 17 Total 0 0 0 0 22 24 46 2201 2247 N.B. To prevent double counting of patients, transferred cases from ORPs to CTCs are not counted in the ORPs. Table 2: Summary of cholera cases reported outside Juba County, 23 April – 5 October 2014 New New New Total cases Total Total admisions discharges deaths Total Total cases Total States Reporting Sites currently facility community 29 Sept to 29 Sept to 29 Sep to deaths discharged cases admitted deaths deaths 5 Oct 2014 5 Oct 2014 5 Oct 14 Kajo-Keji civil hospital 0 0 0 0 -

Ss 9303 Ee Kapoeta North Cou

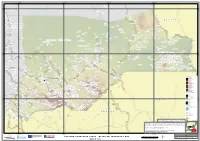

SOUTH SUDAN Kapoeta North County reference map SUDAN Pibor JONGLEI ETHIOPIA CAR DRC KENYA UGANDA EASTERN EQUATORIA Kenyi Lafon Kapoeta East Akitukomoi Kangitabok Lomokori Kapoeta North Ngigalingatun Kangibun Kalopedet Lokidangoai Nomogonjet Nawitapal Mogos Chokagiling Lorutuk Lokoges Nakwa Owetiani Nawabei Natatur Kamaliato Kanyowokol Karibungura Lokale Nagira Belengtobok Tuliabok Lokorechoke Kadapangolol Akoribok Nakwaparich Kalobeliang Wana Kachinga Lomus Lotiakara Pucwa Lopetet Nawao Lokorilam Naduket Tingayta Lodomei Kibak Nakatiti International boundary Nakapangiteng Napusiret Napulak State boundary Loriwo County boundary Kochoto Naminitotit Parpar Undetermined boundary Napusireit Nakwamoru Abyei region Kotak Kasotongor Napochorege Katiakin Nawayareng Riwoto Lokorumor Country capital Nangoletire Lokualem Lumeyen Logerain Lomidila Takankim Lobei Administrative centre/County capital Lokwamor Nacukut Naronyi Nakoret Lotiekar Namukeris Principal town Napotit Naoyatir Nakore Napureit Secondary town Lokwamiro Narubui Barach Lolepon Lotiri Paima Village Loregai Narongyet Lochuloit Kabuni Primary road Kudule Locheler Napusiria Napotpot Secondary road Nacholobo Tertiary road Budi Idong Main river Kapoeta South 0 5 10 km The administrative boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Final boundary between the Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet been determined. Final status of Abyei area is not yet determined. Created: March 2020 | Code: SS-9303 | Sources: OCHA, SSNBS | Feedback: [email protected] | unocha.org/south-sudan | reliefweb.int/country/ssd | southsudan.humanitarianresponse.info . -

Upper Nile State, South Sudan June 2017

Situation Overview: Upper Nile State, South Sudan June 2017 SUDAN Introduction previous REACH assessments of hard-to- presence returned to the averages from April reach areas of Upper Nile State. (22% June, 42% May, 28% April).1 This may Despite a potential respite in fighting in lower MANYO be indicative of the slowing of movement due This Situation Overview outlines displacement counties along the western bank, dispersed to the rainy season. Although fighting that took RENK and access to basic services in Upper Nile fighting and widespread displacements trends place in Panyikang and Fashoda appeared to in June 2017. The first section analyses continued into June and impeded the provision subside, clashes between armed groups armed displacement trends in Upper Nile State. of primary needs and access to basic services groups reportedly commenced in Manyo and The second section outlines the population for assessed settlements. Only 45% of assessed Renk Counties, causing the local population to MELUT dynamics in the assessed settlements, as well settlements reported adequate access to food flee across the border as well as to Renk Town.2 and half reported access to healthcare facilities as access to food and basic services for both FASHODA These clashes may have also contributed to across Upper Nile State, while the malnutrition, MABAN IDP and non-displaced communities. MALAKAL a lack of IDPs, with no assessed settlement malaria and cholera concerns reported in May PANYIKANG BALIET Baliet, Maban, Melut and Renk Counties had in Manyo reporting an IDP presence in June, continued into June. LONGOCHUK less than 5% settlement coverage (Map 1), compared to 50% in May. -

The Crisis in South Sudan

Conflict in South Sudan and the Challenges Ahead Lauren Ploch Blanchard Specialist in African Affairs September 22, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43344 Conflict in South Sudan and the Challenges Ahead Summary South Sudan, which separated from Sudan in 2011 after almost 40 years of civil war, was drawn into a devastating new conflict in late 2013, when a political dispute that overlapped with preexisting ethnic and political fault lines turned violent. Civilians have been routinely targeted in the conflict, often along ethnic lines, and the warring parties have been accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity. The war and resulting humanitarian crisis have displaced more than 2.7 million people, including roughly 200,000 who are sheltering at U.N. peacekeeping bases in the country. Over 1 million South Sudanese have fled as refugees to neighboring countries. No reliable death count exists. U.N. agencies report that the humanitarian situation, already dire with over 40% of the population facing life-threatening hunger, is worsening, as continued conflict spurs a sharp increase in food prices. Famine may be on the horizon. Aid workers, among them hundreds of U.S. citizens, are increasingly under threat—South Sudan overtook Afghanistan as the country with the highest reported number of major attacks on humanitarians in 2015. At least 62 aid workers have been killed during the conflict, and U.N. experts warn that threats are increasing in scope and brutality. In August 2015, the international community welcomed a peace agreement signed by the warring parties, but it did not end the conflict. -

The Criminalization of South Sudan's Gold Sector

The Criminalization of South Sudan’s Gold Sector Kleptocratic Networks and the Gold Trade in Kapoeta By the Enough Project April 2020* A Precious Resource in an Arid Land Within the area historically known as the state of Eastern Equatoria, Kapoeta is a semi-arid rangeland of clay soil dotted with short, thorny shrubs and other vegetation.1 Precious resources lie below this desolate landscape. Eastern Equatoria, along with the region historically known as Central Equatoria, contains some of the most important and best-known sites for artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASM). Some estimates put the number of miners at 60,000 working at 80 different locations in the area, including Nanaknak, Lauro (Didinga Hills), Napotpot, and Namurnyang. Locals primarily use traditional mining techniques, panning for gold from seasonal streams in various villages. The work provides miners’ families resources to support their basic needs.2 Kapoeta’s increasingly coveted gold resources are being smuggled across the border into Kenya with the active complicity of local and national governments. This smuggling network, which involves international mining interests, has contributed to increased militarization.3 Armed actors and corrupt networks are fueling low-intensity conflicts over land, particularly over the ownership of mining sites, and causing the militarization of gold mining in the area. Poor oversight and conflicts over the control of resources between the Kapoeta government and the national government in Juba enrich opportunistic actors both inside and outside South Sudan. Inefficient regulation and poor gold outflows have helped make ASM an ideal target for capture by those who seek to finance armed groups, perpetrate violence, exploit mining communities, and exacerbate divisions. -

South Sudan Humanitarian Situation Report Issue # 23

Bi-Weekly Humanitarian Situation Report Emergency type: Humanitarian crises Issue #: 23 Reporting Weeks: 26 & 27 Dr. Guracha, WHO OIC giving remarks during official launch of MDA by MOH in Juba Date: 24 June – 7 July 2019 .Photo: WHO JuPhoto information & photo credit Humanitarian Situation Update in South Sudan 7.1 M Need 1.9 M Internally 2.3M South Sudanese in Humanitarian Displaced Persons other countries Assistance with 0.2M living in PoC’s 6.96 M 860K 596K Malnourished Severely Food Malnourished Women Insecure Children Key Bi-Weekly Highlights Acute malnutrition 860,000 Acutely Malnourished 1 case of EVD was confirmed in Ariwara in Ituri Province of the DRC, 70 Kms from South 57 Stabilization Centers Sudan’s Kaya border in Yei River State. Cumulative vaccination WHO Rapid Response Team deployed to 182, 223 vaccinated with OPV Vaccine Nimule & Yei to strengthen EVD 167, 363 Vaccinated with Measles preparedness following confirmation of EVD case, 70 KMs from South Sudan’s Border. 7, 783 vaccinated against meningitis MOH & WHO in collaboration with the Ministry of Education jointly launched Public health threats country wide Mass Drug Administration in Juba targeting 1.5 million children. 02 EVD Alerts reported in Yei on 5 & 6 July 2019. MOH, WHO & partners conduct Training of Trainers on Severe Acute Malnutrition with 01 Suspected Cholera case reported in Juba Medical Complication. Protection of Civilians Site (POC3). PCR machine installed at the National Public Health Laboratory in Juba. Sample tested invalid -sent to UVRI for confirmation. 1 Virus Disease Overview of the Humanitarian Situation: humanitarian crises Almost 7 million people facing critical lack of food: 6.96 million (61% of population) people face acute food insecurity in South Sudan– according to UN sources. -

Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan's Equatoria

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 493 | APRIL 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan’s Equatoria By Alan Boswell Contents Introduction ...................................3 Descent into War ..........................4 Key Actors and Interests ............ 9 Conclusion and Recommendations ...................... 16 Thomas Cirillo, leader of the Equatoria-based National Salvation Front militia, addresses the media in Rome on November 2, 2019. (Photo by Andrew Medichini/AP) Summary • In 2016, South Sudan’s war expand- Equatorians—a collection of diverse South Sudan’s transitional period. ed explosively into the country’s minority ethnic groups—are fighting • On a national level, conflict resolu- southern region, Equatoria, trig- for more autonomy, local or regional, tion should pursue shared sover- gering a major refugee crisis. Even and a remedy to what is perceived eignty among South Sudan’s con- after the 2018 peace deal, parts of as (primarily) Dinka hegemony. stituencies and regions, beyond Equatoria continue to be active hot • Equatorian elites lack the external power sharing among elites. To spots for national conflict. support to viably pursue their ob- resolve underlying grievances, the • The war in Equatoria does not fit jectives through violence. The gov- political process should be expand- neatly into the simplified narratives ernment in Juba, meanwhile, lacks ed to include consultations with of South Sudan’s war as a power the capacity and local legitimacy to local community leaders. The con- struggle for the center; nor will it be definitively stamp out the rebellion. stitutional reform process of South addressed by peacebuilding strate- Both sides should pursue a nego- Sudan’s current transitional period gies built off those precepts. -

The Greater Pibor Administrative Area

35 Real but Fragile: The Greater Pibor Administrative Area By Claudio Todisco Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2015 First published in March 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Maison de la Paix, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Copy-edited by Alex Potter ([email protected]) Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Cartography by Jillian Luff (www.mapgrafix.com) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-940548-09-5 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 35 Contents List of abbreviations and acronyms .................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Introduction and key findings .............................................................................................................................................. -

The Role of Indigenous Languages in Southern Sudan: Educational Language Policy and Planning

The Role of Indigenous Languages in Southern Sudan: Educational Language Policy and Planning H. Wani Rondyang A thesis submitted to the Institute of Education, University of London, for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2007 Abstract This thesis aims to questions the language policy of Sudan's central government since independence in 1956. An investigation of the root causes of educational problems, which are seemingly linked to the current language policy, is examined throughout the thesis from Chapter 1 through 9. In specific terms, Chapter 1 foregrounds the discussion of the methods and methodology for this research purposely because the study is based, among other things, on the analysis of historical documents pertaining to events and processes of sociolinguistic significance for this study. The factors and sociolinguistic conditions behind the central government's Arabicisation policy which discourages multilingual development, relate the historical analysis in Chapter 3 to the actual language situation in the country described in Chapter 4. However, both chapters are viewed in the context of theoretical understanding of language situation within multilingualism in Chapter 2. The thesis argues that an accommodating language policy would accord a role for the indigenous Sudanese languages. By extension, it would encourage the development and promotion of those languages and cultures in an essentially linguistically and culturally diverse and multilingual country. Recommendations for such an alternative educational language policy are based on the historical and sociolinguistic findings in chapters 3 and 4 as well as in the subsequent discussions on language policy and planning proper in Chapters 5, where theoretical frameworks for examining such issues are explained, and Chapters 6 through 8, where Sudan's post-independence language policy is discussed. -

LC SS 706 A1 EEQ 20130301.Pdf

pp p ! ! p ! p (! ! !( 32°0'0"E 33°0'0"E 34°0'0"E 35°0'0"E Gwalla Awan KolnyangAluk Katanich Titong Munini Beru ! R . K Wowa ang en Logoda N Rigl Chilimun N " " 0 0 p' Bor South County ' 0 Pibor County Lowelli Katchikan River Bellel Kichepo 0 ° Maktiweng J O N G L E I ° 6 Kaigo 6 Lochiret R. Naro Kenamuke Swamp R Ngechele . S Neria u p Kanopir Natibok Kabalatigo i r i ( B Moru Kimod a Rongada h r Yebisak e g l- n Tombi J o e b b l Shogle e a l) Buka h C . Gwojo-Adung Kassangor R Baro ! E T H I O P I A Moru Kerri KURON Kuron Gigging p Bojo-Ajut Gemmaiza ! Karn Ethi Kerkeng Moru Ethi Nakadocwa Poko Wani Terekeka County Kobowen Swamp Borichadi Bokuna Poko Kassengo Selemani Pagar Nabwel Wani Mika Chabong Tukara C E N T R A L p River Nakua p Kenyi E Q U A T O R I A Moru Angbin Mukajo Gali Owiyabong Kursomba Lotimor Bulu Koli Kalaruz Awakot Katima Waha ! Akitukomoi River Gera Tumu Nanyangachor Nyabongi Napalap ! Namoropus Natilup Swamp ) it Wanyang Kangitabok Lomokori le Eyata Moru Kolinyagkopil il ! Terakeka ri Lozut Lomongole t iti o (! S L Magara p R. ( n Umm Gura Mwanyakapin a p y l Abuilingakine Lomareng Plateau a Dogora R Ngigalingatun k o . L Jelli L o p Rambo Djie Navi . Lokodopotok Nyaginei Kangeleng p R Biyara Nai A o Kworijik Kangibun Lomuleye Katirima t o Simsima Badigeru Swamp River Lokuja Losagam k Musha Lukwatuk Pass Doinyoro East p o p l Balala Legeri Buboli Kalopedet Pongo River Lokorowa Watha Peth Hills Bume E A S T E R N E Q U A T O R I A Lokidangoai Nawitapal Lopokori Lokomarukest Kolobeleng Yakara Dogatwan Nomogonjet Kagethi ! Mogos Bala Pool Lapon County Lotakawa Kanyabu Moru Ethi Donyiro West Donyiro Cliff Kedowa Kothokan a l l i Chokagiling t Karakamuge o Mangalla Bwoda L Mediket Kaliapus Nyangatom !( . -

Political Repression in Sudan

Sudan Page 1 of 243 BEHIND THE RED LINE Political Repression in Sudan Human Rights Watch/Africa Human Rights Watch Copyright © May 1996 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 96-75962 ISBN 1-56432-164-9 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was researched and written by Human Rights Watch Counsel Jemera Rone. Human Rights Watch Leonard H. Sandler Fellow Brian Owsley also conducted research with Ms. Rone during a mission to Khartoum, Sudan, from May 1-June 13, 1995, at the invitation of the Sudanese government. Interviews in Khartoum with nongovernment people and agencies were conducted in private, as agreed with the government before the mission began. Private individuals and groups requested anonymity because of fear of government reprisals. Interviews in Juba, the largest town in the south, were not private and were controlled by Sudan Security, which terminated the visit prematurely. Other interviews were conducted in the United States, Cairo, London and elsewhere after the end of the mission. Ms. Rone conducted further research in Kenya and southern Sudan from March 5-20, 1995. The report was edited by Deputy Program Director Michael McClintock and Human Rights Watch/Africa Executive Director Peter Takirambudde. Acting Counsel Dinah PoKempner reviewed sections of the manuscript and Associate Kerry McArthur provided production assistance. This report could not have been written without the assistance of many Sudanese whose names cannot be disclosed. CONTENTS -

Mining in South Sudan: Opportunities and Risks for Local Communities

» REPORT JANUARY 2016 MINING IN SOUTH SUDAN: OPPORTUNITIES AND RISKS FOR LOCAL COMMUNITIES BASELINE ASSESSMENT OF SMALL-SCALE AND ARTISANAL GOLD MINING IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EQUATORIA STATES, SOUTH SUDAN MINING IN SOUTH SUDAN FOREWORD We are delighted to present you the findings of an assessment conducted between February and May 2015 in two states of South Sudan. With this report, based on dozens of interviews, focus group discussions and community meetings, a multi-disciplinary team of civil society and government representatives from South Sudan are for the first time shedding light on the country’s artisanal and small-scale mining sector. The picture that emerges is a remarkable one: artisanal gold mining in South Sudan ‘employs’ more than 60,000 people and might indirectly benefit almost half a million people. The vast majority of those involved in artisanal mining are poor rural families for whom alluvial gold mining provides critical income to supplement their subsistence livelihood of farming and cattle rearing. Ostensibly to boost income for the cash-strapped government, artisanal mining was formalized under the Mining Act and subsequent Mineral Regulations. However, owing to inadequate information-sharing and a lack of government mining sector staff at local level, artisanal miners and local communities are not aware of these rules. In reality there is almost no official monitoring of artisanal or even small-scale mining activities. Despite the significant positive impact on rural families’ income, the current form of artisanal mining does have negative impacts on health, the environment and social practices. With most artisanal, small-scale and exploration mining taking place in rural areas with abundant small arms and limited presence of government security forces, disputes over land access and ownership exacerbate existing conflicts.