University of California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dueling, Honor and Sensibility in Eighteenth-Century Spanish Sentimental Comedies

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 DUELING, HONOR AND SENSIBILITY IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SPANISH SENTIMENTAL COMEDIES Kristie Bulleit Niemeier University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Niemeier, Kristie Bulleit, "DUELING, HONOR AND SENSIBILITY IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SPANISH SENTIMENTAL COMEDIES" (2010). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 12. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/12 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Kristie Bulleit Niemeier The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2010 DUELING, HONOR AND SENSIBILITY IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SPANISH SENTIMENTAL COMEDIES _________________________________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION _________________________________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the University of Kentucky By Kristie Bulleit Niemeier Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Ana Rueda, Professor of Spanish Literature Lexington, Kentucky 2010 Copyright © Kristie Bulleit Niemeier 2010 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION DUELING, HONOR AND -

Don Juan Contra Don Juan: Apoteosis Del Romanticismo Español

DON JUAN CONTRA DON JUAN: APOTEOSIS DEL ROMANTICISMO ESPAÑOL La imaginación popular hizo de Zorrilla el poeta romántico por excelencia, y de su drama Don Juan Tenorio la encarnación misma del espíritu romántico. Aunque con ciertas vacilaciones, la crítica ha aceptado, al menos parcialmente, ese veredicto: está claro que Zorrilla debe incluirse en la reducida capilla de los dramaturgos ro- mánticos españoles, y su drama, el popularísimo Tenorio, entre las obras más representativas (si no la más representativa) de ese mo- vimiento.1 Pero lo que no está tan claro es el carácter del romanticis- mo zorrülesco —sus raíces, sus alcances, y su lugar dentro de las fronteras del movimiento romántico español. Creo que un estudio de la imaginería y la ideología de Don Juan Tenorio puede revelar- nos la manera en que Zorrilla juntó muchos de los hilos diferentes de la expresión romántica y así creó una obra que es, a la vez, la cima y el fin dramático del movimiento romántico en España.2 Edgar Allison Peers dividió el movimiento romántico en dos direcciones fundamentales: el Redescubrimiento Romántico, que con- tenía los elementos de la virtud caballeresca, el cristianismo, los va- leres medievales y la monarquía, y la Rebelión Romántica, que in- 1) Ver Narciso Alonso Cortés, Zorrilla, su vida y sus obras (Valladolid, Santa- rén, 1943); Luz Rubio Fernández, «Variaciones estilísticas del "Tenorio"», Revista de Literatura, 19 (1961), págs. 55-92; Luis Muñoz González, «Don Juan Tenorio, la personificación del mito», Estudios Filológicos, 10 (1974-1975), págs. 93-122; y el excelente estudio de Roberto G. Sánchez, « Between Maciías and Don Juan: Spa- nish Romantic Drama and the Mythology of Love», Hispanic Review, 44 (1976), págs. -

Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930S

Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930s Ariel Mae Lambe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Ariel Mae Lambe All rights reserved ABSTRACT Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930s Ariel Mae Lambe This dissertation shows that during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) diverse Cubans organized to support the Spanish Second Republic, overcoming differences to coalesce around a movement they defined as antifascism. Hundreds of Cuban volunteers—more than from any other Latin American country—traveled to Spain to fight for the Republic in both the International Brigades and the regular Republican forces, to provide medical care, and to serve in other support roles; children, women, and men back home worked together to raise substantial monetary and material aid for Spanish children during the war; and longstanding groups on the island including black associations, Freemasons, anarchists, and the Communist Party leveraged organizational and publishing resources to raise awareness, garner support, fund, and otherwise assist the cause. The dissertation studies Cuban antifascist individuals, campaigns, organizations, and networks operating transnationally to help the Spanish Republic, contextualizing these efforts in Cuba’s internal struggles of the 1930s. It argues that both transnational solidarity and domestic concerns defined Cuban antifascism. First, Cubans confronting crises of democracy at home and in Spain believed fascism threatened them directly. Citing examples in Ethiopia, China, Europe, and Latin America, Cuban antifascists—like many others—feared a worldwide menace posed by fascism’s spread. -

Top 100 Most Requested Latin Songs

Top 100 Most Requested Latin Songs Based on millions of requests played and tracked through the DJ Intelligence® music request system at weddings & parties throughout 201 9 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Luis Fonsi & Daddy Yankee Feat. Justin Bieber Despacito 2 Pitbull Feat. John Ryan Fireball 3 Jennifer Lopez Feat. Pitbull On The Floor 4 Cardi B Feat. Bad Bunny & J Balvin I Like It 5 Pitbull Feat. Ne-Yo, Afrojack & Nayer Give Me Everything 6 Marc Anthony Vivir Mi Vida 7 Elvis Crespo Suavemente 8 Bad Bunny Feat. Drake Mia 9 Pitbull Feat. Ne-Yo Time Of Our Lives 10 DJ Snake Feat. Cardi B, Ozuna & Selena Gomez Taki Taki 11 Gente De Zona Feat. Marc Anthony La Gozadera 12 Daddy Yankee Gasolina 13 Prince Royce Corazon Sin Cara 14 Daddy Yankee Dura 15 Shakira Feat. Maluma Chantaje 16 Celia Cruz La Vida Es Un Carnaval 17 Prince Royce Stand By Me 18 Daddy Yankee Limbo 19 Nicky Jam & J Balvin X 20 Carlos Vives & Shakira La Bicicleta 21 Daddy Yankee & Katy Perry Feat. Snow Con Calma 22 Luis Fonsi & Demi Lovato Echame La Culpa 23 J Balvin Ginza 24 Becky G Feat. Bad Bunny Mayores 25 Ricky Martin Feat. Maluma Vente Pa' Ca 26 Nicky Jam Hasta El Amanecer 27 Prince Royce Darte Un Beso 28 Romeo Santos Feat. Usher Promise 29 Romeo Santos Propuesta Indecente 30 Pitbull Feat. Chris Brown International Love 31 Maluma Felices Los 4 32 Pitbull Feat. Christina Aguilera Feel This Moment 33 Alexandra Stan Mr. Saxobeat 34 Daddy Yankee Shaky Shaky 35 Marc Anthony Valio La Pena 36 Azul Azul La Bomba 37 Carlos Vives Volvi A Nacer 38 Maluma Feat. -

Emergence of the State Constitution Is the Duty of All Citizens of Myanmar Naing-Ngan

Established 1914 Volume XII, Number 354 12th Waning of Taboung 1366 ME Tuesday, 5 April 2005 Four political objectives Four economic objectives Four social objectives * Stability of the State, community peace * Development of agriculture as the base and all-round * Uplift of the morale and morality of and tranquillity, prevalence of law and development of other sectors of the economy as well the entire nation order * Proper evolution of the market-oriented economic * Uplift of national prestige and integ- * National reconsolidation system rity and preservation and safeguard- * Emergence of a new enduring State * Development of the economy inviting participation in ing of cultural heritage and national Constitution terms of technical know-how and investments from character * Building of a new modern developed sources inside the country and abroad * Uplift of dynamism of patriotic spirit nation in accord with the new State * The initiative to shape the national economy must be kept * Uplift of health, fitness and education Constitution in the hands of the State and the national peoples standards of the entire nation Senior General Than Shwe Excerpts from Senior General Than Shwe’s speech sends message of condolence * The population of Myeik has been on the increase with the emergence of oil palm and rubber growing undertakings and to Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger fish and meat industry in the region. * Arrangements are to be made for developing a new town from YANGON, 4 April— Senior General Than Shwe, Chairman of now on for serving long-term interest. the State Peace and Development Council of the Union of * The government on its part will provide all the necessary aids Myanmar, has sent a message of condolence to His Eminence for the emergence of a new town complete with health, social Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, Dean of the Sacred College, Congre- and transport sectors of higher standard. -

The Specter of Franco

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2014 The Specter of Franco Alexandra L. Jones University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Alexandra L., "The Specter of Franco" (2014). Honors Theses. 27. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/27 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SPECTER OF FRANCO ©2014 Alexandra Leigh Jones A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies Croft Institute for International Studies Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi May 2014 Approved by Advisor: Dr. Manuel Sosa-Ramirez Reader: Dr. William Schenck Reader: Professor Melissa Graves ABSTRACT Human rights violations that occurred almost seventy years ago are still a social issue in Spain today. This project analyzed five post- Franco films that dealt with the issue of the Spanish Civil War or Franco regime to determine if they were a counter to official political discourse on the subject. In addition to analyzing the films themselves, research was also done on a variety of official discourse pertaining to the recovery of memory in Spain. Upon examination it became clear that the overarching discourse in Spain is a refusal to address the issues of the past. -

E08bff68148321589893341.Pdf

Brevard Live January 2017- 1 2 - Brevard Live January 2017 Brevard Live January 2017- 3 4 - Brevard Live January 2017 Brevard Live January 2017- 5 6 - Brevard Live January 2017 Contents January 2017 FEATURES SEAFOOD & MUSIC FESTIVAL PETER YARROW Now held at Shepard Park in Cocoa Columns Beach, the festival features the freshest Peter Yarrow found fame with the 1960s Charles Van Riper folk music trio Peter, Paul and Mary. seafood along with some amazing live entertainment: mega-star, singer- and 22 Political Satire Yarrow co-wrote (with Leonard Lipton) “The Column” one of the group’s greatest hits, “Puff, songwriter, legend John McLean and the Magic Dragon”. reggae legends, The Original Wailers. Page 17 Calendars Page 11 25 Live Entertainment, Concerts, Festivals TRAVIS DAIGLE IRELAND The next generation of “guitar heroes Take yourself to another time and place Local Download in the making” has arrived. Meet Travis and drink in the history of the enchant- by Andy Harrington Daigle who has recently recorded an EP 33 ing Emerald Isle. You haven’t been to Local Music Scene with the help of rock legends David Pas- Ireland until you’ve experienced all the torius and Kenny “Rhino” Earl. They are drunk, the loud, and the wild there is to In The Spotlight featured on our cover this month. offer. John Leach was among them. 35 by Matt Bretz Page 13 Page 17 Flori-duh! TITUSVILLE MARDI GRAS ANDY STANFIELD 36 by Charles Knight Historic downtown Titusville will trans- We first met Andy in 2012 when he ap- form into a New Orleans style French peared with his band Pipes of Pan during The Dope Doctor Quarter during the Titusville Mardi Gras the Original Music Series. -

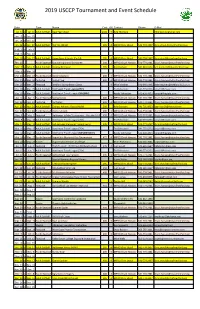

2019 USCCP Tournament and Event Schedule

2019 USCCP Tournament and Event Schedule Date Type Name Cost GG Contact Phone E-Mail Jan. 5 to Jan. 6 Adult Softball New Year's Bash $300 4 Kyle Thomson [email protected] Jan. 12 to Jan. 13 Jan. 19 to Jan. 20 Jan. 26 to Jan. 27 Adult Softball The Yeti (M/W) 295 4 MPRD/Chris Shaull 541-774-2407 [email protected] Feb. 2 to Feb. 3 Feb. 9 to Feb. 10 Feb. 16 to Feb. 17 Adult Softball Home Runs 4 Hearts (Co-Ed) 295 4 MPRD/Chris Shaull 541-774-2407 [email protected] Feb. 23 Youth Baseball Groundhog Grand Slamboree 200 2 MPRD/Chuck Hanson 541-774-2481 [email protected] Mar. 2 to Mar. 3 Adult Softball Holiday RV Classic 295 Ken Parducci 541-840-6534 [email protected] Mar. 9 to Mar. 10 Mar. 16 to Mar. 17 Youth Baseball March Mayhem 400 3 MPRD/Chuck Hanson 541-774-2481 [email protected] Mar. 23 to Mar. 24 Fastpitch Spring Fling 400 4 MPRD/Chuck Hanson 541-774-2481 [email protected] Mar. 25 to Mar. 26 Fastpitch Medford Spring Break Classic 4 Mike Mayben 541-646-0405 [email protected] Mar. 28 to Mar. 29 Adult Softball Northwest Travel League (70+) Ted Schroeder 541-773-6226 [email protected]@charter.net Mar. 30 to Mar. 31 Adult Softball Northwest Travel League (50+)(63+) Randy Schmelzer 541-690-4813 [email protected] Apr. 6 to Apr. 7 Youth Baseball Spring Classic 400 3 MPRD/Chuck Hanson 541-774-2481 [email protected] Apr. -

The Politics of Bulls and Bullfights in Contemporary Spain

SOCIAL THOUGHT & COMMENTARY Torophies and Torphobes: The Politics of Bulls and Bullfights in Contemporary Spain Stanley Brandes University of California, Berkeley Abstract Although the bullfight as a public spectacle extends throughout southwestern Europe and much of Latin America, it attains greatest political, cultural, and symbolic salience in Spain. Yet within Spain today, the bullfight has come under serious attack, from at least three sources: (1) Catalan nationalists, (2) Spaniards who identify with the new Europe, and (3) increasingly vocal animal rights advocates. This article explores the current debate—cultural, political, and ethical—on bulls and bullfighting within the Spanish state, and explores the sources of recent controversy on this issue. [Keywords: Spain, bullfighting, Catalonia, animal rights, public spectacle, nationalism, European Union] 779 Torophies and Torphobes: The Politics of Bulls and Bullfights in Contemporary Spain s is well known, the bullfight as a public spectacle extends through- A out southwestern Europe (e.g., Campbell 1932, Colomb and Thorel 2005, Saumade 1994), particularly southern France, Portugal, and Spain. It is in Spain alone, however, that this custom has attained notable polit- ical, cultural, and symbolic salience. For many Spaniards, the bull is a quasi-sacred creature (Pérez Álvarez 2004), the bullfight a display of exceptional artistry. Tourists consider bullfights virtually synonymous with Spain and flock to these events as a source of exotic entertainment. My impression, in fact, is that bullfighting is even more closely associated with Spanish national identity than baseball is to that of the United States. Garry Marvin puts the matter well when he writes that the cultur- al significance of the bullfight is “suggested by its general popular image as something quintessentially Spanish, by the considerable attention paid to it within Spain, and because of its status as an elaborate and spectacu- lar ritual drama which is staged as an essential part of many important celebrations” (Marvin 1988:xv). -

The Grottesche Part 1. Fragment to Field

CHAPTER 11 The Grottesche Part 1. Fragment to Field We touched on the grottesche as a mode of aggregating decorative fragments into structures which could display the artist’s mastery of design and imagi- native invention.1 The grottesche show the far-reaching transformation which had occurred in the conception and handling of ornament, with the exaltation of antiquity and the growth of ideas of artistic style, fed by a confluence of rhe- torical and Aristotelian thought.2 They exhibit a decorative style which spreads through painted façades, church and palace decoration, frames, furnishings, intermediary spaces and areas of ‘licence’ such as gardens.3 Such proliferation shows the flexibility of candelabra, peopled acanthus or arabesque ornament, which can be readily adapted to various shapes and registers; the grottesche also illustrate the kind of ornament which flourished under printing. With their lack of narrative, end or occasion, they can be used throughout a context, and so achieve a unifying decorative mode. In this ease of application lies a reason for their prolific success as the characteristic form of Renaissance ornament, and their centrality to later historicist readings of ornament as period style. This appears in their success in Neo-Renaissance style and nineteenth century 1 The extant drawings of antique ornament by Giuliano da Sangallo, Amico Aspertini, Jacopo Ripanda, Bambaia and the artists of the Codex Escurialensis are contemporary with—or reflect—the exploration of the Domus Aurea. On the influence of the Domus Aurea in the formation of the grottesche, see Nicole Dacos, La Découverte de la Domus Aurea et la Formation des grotesques à la Renaissance (London: Warburg Institute, Leiden: Brill, 1969); idem, “Ghirlandaio et l’antique”, Bulletin de l’Institut Historique Belge de Rome 39 (1962), 419– 55; idem, Le Logge di Raffaello: Maestro e bottega di fronte all’antica (Rome: Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato, 1977, 2nd ed. -

Don Juan Tenorio

José Zorrilla Don Juan Tenorio Colección Averroes Colección Averroes Consejería de Educación y Ciencia Junta de Andalucía ÍNDICE Parte primera ......................................................................... 9 Acto primero ..................................................................... 9 Escena I......................................................................... 9 Escena II.......................................................................12 Escena III .....................................................................15 Escena IV .....................................................................16 Escena V ......................................................................16 Escena VI .....................................................................19 Escena VII....................................................................19 Escena VIII...................................................................21 Escena IX .....................................................................23 Escena X ......................................................................24 Escena XI .....................................................................25 Escena XII....................................................................28 Escena XIII...................................................................44 Escena XIV ..................................................................45 Escena XV....................................................................46 Acto segundo....................................................................48 -

La Vida Secreta De Las Palabras, Galardonada Con El XI Premio Cinematográfico José María Forqué

EGEDA BOLETIN 42-43 8/6/06 11:44 Página 1 No 42-43. 2006 Entidad autorizada por el Ministerio de Cultura para la representación, protección y defensa de los intereses de los productores audiovisuales, y de sus derechos de propiedad intelectual. (Orden de 29-10-1990 - B.O.E., 2 de Noviembre de 1990) La vida secreta de las palabras, galardonada con el XI Premio Cinematográfico José María Forqué Una historia de soledad e incomunicación, La vida secreta de las palabras, producida por El Deseo y Mediapro y dirigida por Isabel Coixet, ha sido galardonada con el Premio José María Forqué, que este año ha llegado a su undécima edición. En la gala, celebrada en el Teatro Real el 9 de mayo, La vida secreta de las palabras compartió homenaje con el documental El cielo gira, que se llevó el IV Premio Especial EGEDA, y con el productor Andrés Vicente Gómez, galardonado con la Medalla de Oro (Foto: Pipo Fernández) (Foto: de EGEDA por el conjunto de su carrera. La gala tuvo como maestros de ceremo- cida por Maestranza Films, ICAIC y Pyra- vertirán a los creadores españoles en los nias a Concha Velasco y Jorge Sanz, y con- mide Productions, y dirigida por Benito más protegidos de Europa. tó con la actuación musical del Grupo Sil- Zambrano; Obaba, producida por Oria ver Tones, que interpretó temas de rock Films, Pandora Film y Neue Impuls Film, y Por su parte, el presidente de EGEDA, En- and roll de los años 50 y 60. Esto supone dirigida por Montxo Armendáriz, y Prince- rique Cerezo, entregó la Medalla de Oro una novedad en el escenario del Teatro sas, producida por Reposado PC y Media- de la entidad al veterano productor An- Real, pues es la primera vez que acoge este pro, y dirigida por Fernando León de Ara- drés Vicente Gómez en reconocimiento “a género musical.