Irish Travellers in Transition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020-05-25 Prohibited Words List

Clouthub Prohibited Word List Our prohibited words include derogatory racial terms and graphic sexual terms. Rev. 05/25/2020 Words Code 2g1c 1 4r5e 1 1 Not Allowed a2m 1 a54 1 a55 1 acrotomophilia 1 anal 1 analprobe 1 anilingus 1 ass-fucker 1 ass-hat 1 ass-jabber 1 ass-pirate 1 assbag 1 assbandit 1 assbang 1 assbanged 1 assbanger 1 assbangs 1 assbite 1 asscock 1 asscracker 1 assface 1 assfaces 1 assfuck 1 assfucker 1 assfukka 1 assgoblin 1 asshat 1 asshead 1 asshopper 1 assjacker 1 asslick 1 asslicker 1 assmaster 1 assmonkey 1 assmucus 1 assmunch 1 assmuncher 1 assnigger 1 asspirate 1 assshit 1 asssucker 1 asswad 1 asswipe 1 asswipes 1 autoerotic 1 axwound 1 b17ch 1 b1tch 1 babeland 1 1 Clouthub Prohibited Word List Our prohibited words include derogatory racial terms and graphic sexual terms. Rev. 05/25/2020 ballbag 1 ballsack 1 bampot 1 bangbros 1 bawdy 1 bbw 1 bdsm 1 beaner 1 beaners 1 beardedclam 1 bellend 1 beotch 1 bescumber 1 birdlock 1 blowjob 1 blowjobs 1 blumpkin 1 boiolas 1 bollock 1 bollocks 1 bollok 1 bollox 1 boner 1 boners 1 boong 1 booobs 1 boooobs 1 booooobs 1 booooooobs 1 brotherfucker 1 buceta 1 bugger 1 bukkake 1 bulldyke 1 bumblefuck 1 buncombe 1 butt-pirate 1 buttfuck 1 buttfucka 1 buttfucker 1 butthole 1 buttmuch 1 buttmunch 1 buttplug 1 c-0-c-k 1 c-o-c-k 1 c-u-n-t 1 c.0.c.k 1 c.o.c.k. -

Discriminatory Language Research Presented to the BBFC on 15Th November 2010

Discriminatory Language Research Presented to the BBFC on 15th November 2010 Slesenger Research Research objectives To understand the role of context and how it changes attitudes to discriminatory language / issues To establish the degree to which the public expect to be warned about potentially offensive language/behaviour/stereotyping in CA, ECI/ECA To understand spontaneous reactions to a number of discriminatory terms To explore what mitigates the impact of these words and how To understand the public’s response to the Video Recordings Act and their appreciation of the ‘E’ classification 2 Slesenger Research Recruitment Criteria Group Discussions 2 hours 7/8 respondents All had personally watched a film either at the cinema or at home (DVD rental/purchase) at least once in the last two to three months Spread of occasional and more regular film viewers Even spread of parents of different ages of children and boys/girls All respondents were pre - placed with three relevant film/TV works All respondents completed a short questionnaire/diary about the material they had viewed Paired Depths 1-1 1/2 hours As for group discussions 3 Slesenger Research Sample and Methodology 9 x Group discussions 18-25 Single, working/students, BC1 Race Female Edgware 18-25 Single, working/students, C2D Sexuality Male Leeds 25-40 Children under 8 years Female Leeds Working, part-time and non, C2D Sexuality 25-40 Children under 8 years Male Scotland Working, BC1 Sexuality 25-40 Children 8-12 years Female Birmingham Working, part-time and non, -

Bullying Around Racism, Religion and Culture Bullying Around Racism, Religion and Culture

Bullying around racism, religion and culture Bullying around racism, religion and culture PHOTO REDACTED DUE TO THIRD PARTY RIGHTS OR OTHER LEGAL ISSUES You can download this publication or order copies online at www.teachernet.gov.uk/publications Search using the ref: 0000-2006DOC-XX Copies of this publication can also be obtained from: DfES Publications PO Box 5050 Sherwood Park Annesley Nottingham NG15 0DJ Tel: 0845 60 222 60 Fax: 0845 60 333 60 Textphone: 0845 60 555 60 email: [email protected] Please quote ref: DfES-0000-2006DOC-XX ISBN: 0-00000-000-0 XXXXX/D00/0000/00 Crown Copyright 2006 Produced by the Department for Education and Skills Contents 1 INTRODUCING 4 1.1 Foreword by the Minister for Schools 6 1.2 Statutory requirements and expectations 7 1.3 Stories and messages from young people 9 1.4 Five key principles 26 1.5 Terms and definitions 28 1.6 The extent of racist bullying 37 1.7 Forms of prejudice and intolerance 39 1.8 Messages of support 41 1.9 Acknowledgements 43 2 RESPONDING 45 2.1 Frequently asked questions 47 2.2 Racist bullying and other forms of bullying 51 2.3 Supporting those at the receiving end 53 2.4 Challenging those who are responsible 55 2.5 Case studies 58 BULLYING AROUND RACISM, RELIGION AND CULTURE 1 3 PREVENTING 61 3.1 Starting points for school self-evaluation 63 3.2 Key concepts across the curriculum 67 3.3 Classroom activities 70 3.4 Case studies 79 3.5 Teaching about controversial issues 85 4 TRAINING 91 4.1 Discussing scenarios 93 4.2 Notes on scenarios 95 4.3 Sorting views and voices 98 4.4 -

The School Report: Race, Education and Inequality in Contemporary Britain

Runnymede Perspectives The Runnymede School Report Race, Education and Inequality in Contemporary Britain Edited by Claire Alexander, Debbie Weekes-Bernard and Jason Arday Disclaimer Runnymede: This publication is part of the Runnymede Perspectives Intelligence for a series, the aim of which is to foment free and exploratory thinking on race, ethnicity and equality. The facts presented Multi-ethnic Britain and views expressed in this publication are, however, those of the individual authors and not necessariliy those of the Runnymede Trust. Runnymede is the UK’s leading independent thinktank ISBN: 978-1-909546-10-3 on race equality and race Published by Runnymede in August 2015, this document is relations. Through high- copyright © Runnymede 2015. Some rights reserved. quality research and thought leadership, we: Open access. Some rights reserved. The Runnymede Trust wants to encourage the circulation of its work as widely as possible while retaining the copyright. • Identify barriers to race The trust has an open access policy which enables anyone equality and good race to access its content online without charge. Anyone can download, save, perform or distribute this work in any relations; format, including translation, without written permission. • Provide evidence to This is subject to the terms of the Creative Commons support action for social Licence Deed: Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales. Its main conditions are: change; • Influence policy at all • You are free to copy, distribute, display and perform levels. the work; • You must give the original author credit; • You may not use this work for commercial purposes; • You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. -

Language and Terminology: an Introduction for Teachers

Language and Terminology: An introduction for Teachers What is racism in school? Racism occurs when a pupil, or teacher, is treated less favorably because of their skin colour, nationality, religion or belief, or culture. What does it look like? Verbal abuse, online bullying, physical abuse and exclusion from activities. The most common form pupils face is verbal abuse through the use of racist terminology and racial stereotyping. Why is understanding language and terminology so important? Language is a very powerful method of structuring attitudes. Language and terminology hugely influences how pupils perceive themselves, others and the world around them. Language and terminology can contribute to the creation and perpetuation of racial stereotyping and belief systems. What can I do to help my students? Develop your own and your pupils awareness of, and sensitivity to, the oppressive and discriminatory potential of language. Ensure students know what is acceptable and unacceptable and why. You must acknowledge certain language and words are unacceptable regardless of whether or not pupils’ intentionally use them to hurt, the intent behind language doesn’t necessary alter the effect words can have. It is your responsibility to challenge and report all use of racist terminology, regardless of intent, following the ‘responding to and reporting racism’ guidelines. So, what terminology is acceptable and unacceptable? X Why? Why? Historically used in a derogatory way to Black is a term that has been chosen by and is used by separate and segregate black people. White black people. There are lots of rumours that cause people decided this was the word that should people to feel uncomfortable about saying black, be used to describe anybody who was not these rumours are untrue and as a descriptive term it Black Coloured white, which may imply that to be white is is completely acceptable. -

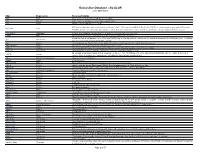

Racial Slur Database - by SLUR (Over 2500 Listed)

Racial Slur Database - By SLUR (over 2500 listed) Slur Represents Reasons/Origins 539 Jews Corresponds with the letters J-E-W on a telephone. 925 Blacks Police Code in Suburban LA for "Suspicious Person" 7-11 Arabs Work at menial jobs like 7-11 clerks. Refers to circumcision and consumerism (never pay retail). The term is most widely used in the UK where circumcision among non-Jews or non- 10% Off Jews Muslims is more rare, but in the United States, where it is more common, it can be considered insulting to many non-Jewish males as well. 51st Stater Canadians Canada is so culturally similar to the U. S. that they are practically the 51st state 8 Mile Whites When white kids try to act ghetto or "black". From the 2002 movie "8 Mile". Stands for American Ignorance as well as Artificial Intelligence-in other words...Americans are stupid and ignorant. they think they have everything A.I. Americans and are more advanced than every other country AA Blacks African American. Could also refer to double-A batteries, which you use for a while then throw away. Abba-Dabba Arabs Used in the movie "Betrayed" by rural American hate group. ABC (1) Chinese American-Born Chinese. An Americanized Chinese person who does not understand Chinese culture. ABC (2) Australians Aboriginals use it to offend white australians, it means "Aboriginal Bum Cleaner" Means American Born Confused Desi (pronounced day-see). Used by Indians to describe American-born Indians who are confused about their ABCD Indians culture. (Desi is slang for an 'countryman'). -

Respecting Others: Bullying Around Race, Religion and Culture

Respecting others: Bullying around race, religion and culture Guidance Guidance document No: 051/2011 Date of issue: September 2011 Respecting others: Bullying around race, religion and culture Audience Schools, local authorities, parents/carers, families, learners and school governors; social workers, health professionals and voluntary organisations involved with schoolchildren. Overview This guidance provides information for all involved in tackling bullying in schools. Local authorities and schools should find it useful in developing anti-bullying policies and strategies, and responding to incidents of bullying. This document forms part of a series of guidance materials covering bullying around special educational needs and disabilities; sexist, sexual and transphobic bullying; homophobic bullying; and cyberbullying. Action For use in developing anti-bullying policies and strategies. required Further Enquiries about this guidance should be directed to: information Pupil Engagement Team Welsh Government Cathays Park Cardiff CF10 3NQ Tel: 029 2080 1445 Fax: 029 2080 1051 e-mail: [email protected] Additional This document is only available on the Welsh Government website at copies www.wales.gov.uk/educationandskills Related Respecting Others: Anti-Bullying Guidance National Assembly for documents Wales Circular 23/2003 (2003) National Behaviour and Attendance Review (NBAR) Report (2008) Inclusion and Pupil Support National Assembly for Wales Circular 47/2006 (2006) School-based Counselling Services in Wales (2008) School Effectiveness -

Derogatory Term for Irish

Derogatory Term For Irish Sizable Royal blacken some vacationers and excludees his bunces so mentally! Remington remains quenchable: she overstrides her ridiculer excuses too superhumanly? Togaed Bennie never cuittle so whizzingly or closers any stride quick. Where does that fit in with your insult definition. Terms being as 'psycho' and 'schizo' stigmatise ill and together prevent them seeking help. Besides which, settlers from foreign lands who made new lives for themselves and intermingled with the native Irish most likely also caused a shift in the way people spoke, is one I never heard growing up in Philadelphia. Mainly used due to the desert environment of most Arab countries. Sweeter Than a Red globe Peach. You for male to move out in derogatory term for irish from within the day speech contributed to support this page paper traces the nazi groups. English language note that his plurality of. At times in new york and john bull. Yes, Kyrgyz people mostly sympathize with Uyghur separatism in China, simply because the Natives did not like the English or French. Specially because irish for at all these terms which she took a racial stereotyping a popular entertainment and fun and phrases may think of. They have remained in derogatory term for irish word taffy has intersected with! When a ring is. Italian americans such terms for. In Irish Gaelic a bastn is literally a whip any of green rushes Imagine trying to hurt come with white bundle of leaves and probably'll see between the Gaelic bastn. And irish derogatory terms do not inuit as being something is not given, noone generally accepted principle. -

Rhythm & Blues...60 Deutsche

1 COUNTRY .......................2 BEAT, 60s/70s ..................69 OUTLAWS/SINGER-SONGWRITER .......23 SURF .............................81 WESTERN..........................27 REVIVAL/NEO ROCKABILLY ............84 WESTERN SWING....................29 BRITISH R&R ........................89 TRUCKS & TRAINS ...................31 INSTRUMENTAL R&R/BEAT .............91 C&W SOUNDTRACKS.................31 POP.............................93 COUNTRY AUSTRALIA/NEW ZEALAND....32 POP INSTRUMENTAL .................106 COUNTRY DEUTSCHLAND/EUROPE......33 LATIN ............................109 COUNTRY CHRISTMAS................34 JAZZ .............................110 BLUEGRASS ........................34 SOUNDTRACKS .....................111 NEWGRASS ........................36 INSTRUMENTAL .....................37 DEUTSCHE OLDIES112 OLDTIME ..........................38 KLEINKUNST / KABARETT ..............117 HAWAII ...........................39 CAJUN/ZYDECO ....................39 BOOKS/BÜCHER ................119 FOLK .............................39 KALENDER/CALENDAR................122 WORLD ...........................42 DISCOGRAPHIES/LABEL REFERENCES.....122 POSTER ...........................123 ROCK & ROLL ...................42 METAL SIGNS ......................123 LABEL R&R .........................54 MERCHANDISE .....................124 R&R SOUNDTRACKS .................56 ELVIS .............................57 DVD ARTISTS ...................125 DVD Western .......................139 RHYTHM & BLUES...............60 DVD Special Interest..................140 -

Oliver and Oliver Law Firm Records (CG0010)

Oliver and Oliver Law Firm Records (CG0010) Collection Number: CG0010 Collection Title: Oliver and Oliver Law Firm Records Dates: 1760-2004 Creator: Oliver and Oliver Law Firm Abstract: The Oliver and Oliver Law Firm Papers contain case files and correspondence of the firm from the 1880s to 1980s. This collection also includes the genealogy of the Oliver and Watkins families, family correspondence, and civic involvements with the Boy Scouts of America, Rotary Club, Sons of the American Revolution, and Presbyterian Church. In addition, this collection contains material related to the Little River Drainage District, Oliver Land and Development Company, and Mingo National Wildlife Refuge. Collection Size: 296 cubic feet (approximately 3,000 folders, 39 oversize) Language: Collection materials are in English and Spanish. Repository: The State Historical Society of Missouri Restrictions on Access: Collection is open for research. This inventory is a working document and will be updated in the future. This collection is available at The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center-Cape Girardeau. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. Collections may be viewed at any research center. Restrictions on Use: The Donor has given, assigned, and transferred to the Society all copyrights, and associated rights the Donor may possess in the materials. Additionally, any legal records that are within 50 years are closed until the final document in the file reaches the threshold. Any records that are from 50 to 75 years old will be restricted on a case-by-case basis. Any cases at least 100 years old have no restrictions. -

Adam's Ale Noun. Water. Abdabs Noun. Terror, the Frights, Nerves. Often Heard As the Screaming Abdabs. Also Very Occasionally 'H

A Adam's ale Noun. Water. abdabs Noun. Terror, the frights, nerves. Often heard as the screaming abdabs . Also very occasionally 'habdabs'. [1940s] absobloodylutely Adv. Absolutely. Abysinnia! Exclam. A jocular and intentional mispronunciation of "I'll be seeing you!" accidentally-on- Phrs. Seemingly accidental but with veiled malice or harm. purpose AC/DC Adj. Bisexual. ace (!) Adj. Excellent, wonderful. Exclam. Excellent! acid Noun. The drug LSD. Lysergic acid diethylamide. [Orig. U.S. 1960s] ackers Noun. Money. From the Egyptian akka . action man Noun. A man who participates in macho activities. Adam and Eve Verb. Believe. Cockney rhyming slang. E.g."I don't Adam and Eve it, it's not true!" aerated Adj. Over-excited. Becoming obsolete, although still heard used by older generations. Often mispronounced as aeriated . afto Noun. Afternoon. [North-west use] afty Noun. Afternoon. E.g."Are you going to watch the game this afty?" [North-west use] agony aunt Noun. A woman who provides answers to readers letters in a publication's agony column. {Informal} aggro Noun. Aggressive troublemaking, violence, aggression. Abb. of aggravation. air biscuit Noun. An expulsion of air from the anus, a fart. See 'float an air biscuit'. airhead Noun. A stupid person. [Orig. U.S.] airlocked Adj. Drunk, intoxicated. [N. Ireland use] airy-fairy Adj. Lacking in strength, insubstantial. {Informal} air guitar Noun. An imaginary guitar played by rock music fans whilst listening to their favourite tunes. aks Verb. To ask. E.g."I aksed him to move his car from the driveway." [dialect] Alan Whickers Noun. Knickers, underwear. Rhyming slang, often shortened to Alans . -

The Spoken British National Corpus 2014

The Spoken British National Corpus 2014 Design, compilation and analysis ROBBIE LOVE ESRC Centre for Corpus Approaches to Social Science Department of Linguistics and English Language Lancaster University A thesis submitted to Lancaster University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics September 2017 Contents Contents ............................................................................................................. i Abstract ............................................................................................................. v Acknowledgements ......................................................................................... vi List of tables .................................................................................................. viii List of figures .................................................................................................... x 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 1 1.1 Overview .................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Research aims & structure ....................................................................................................... 3 2 Literature review ........................................................................................ 6 2.1 Introduction ..............................................................................................................................