Towards a Model of Group-Based Cyberbullying: Combining Verbal Aggression and Manipulation Approaches with Perception Data to In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Islamophobia Monitoring Month: December 2020

ORGANIZATION OF ISLAMIC COOPERATION Political Affairs Department Islamophobia Observatory Islamophobia Monitoring Month: December 2020 OIC Islamophobia Observatory Issue: December 2020 Islamophobia Status (DEC 20) Manifestation Positive Developments 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Asia Australia Europe International North America Organizations Manifestations Per Type/Continent (DEC 20) 9 8 7 Count of Discrimination 6 Count of Verbal & Physical Assault 5 Count of Hate Speech Count of Online Hate 4 Count of Hijab Incidents 3 Count of Mosque Incidents 2 Count of Policy Related 1 0 Asia Australia Europe North America 1 MANIFESTATION (DEC 20) Count of Discrimination 20% Count of Policy Related 44% Count of Verbal & Physical Assault 10% Count of Hate Speech 3% Count of Online Hate Count of Mosque Count of Hijab 7% Incidents Incidents 13% 3% Count of Positive Development on Count of Positive POSITIVE DEVELOPMENT Inter-Faiths Development on (DEC 20) 6% Hijab 3% Count of Public Policy 27% Count of Counter- balances on Far- Rights 27% Count of Police Arrests 10% Count of Positive Count of Court Views on Islam Decisions and Trials 10% 17% 2 MANIFESTATIONS OF ISLAMOPHOBIA NORTH AMERICA IsP140001-USA: New FBI Hate Crimes Report Spurs U.S. Muslims, Jews to Press for NO HATE Act Passage — On November 16, the USA’s Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), released its annual report on hate crime statistics for 2019. According to the Muslim-Jewish Advisory Council (MJAC), the report grossly underestimated the number of hate crimes, as participation by local law enforcement agencies in the FBI's hate crime data collection system was not mandatory. -

Aug – Julie Burchill

2004/August JULIE BURCHILL– Publishing News Julie Burchill. Where exactly do you start? Opinions differ wildly - she’s been described on the one hand as ‘the Queen of English journalism’, and also as ‘the hack from hell’ - but one thing is pretty constant, she is never, ever ignored. For last almost 30 years, from her punk days on the NME to her most recent move from the Guardian to the Times, she has delighted in outraging her detractors and surprising her fans. And now? Now she’s written a teenage novel. Burchill is no stranger to the world of publishing, having produced many books, including the definitive S&F novel Ambition, plus newspaper and magazine columns and works of non-fiction, so why a teen novel? “It doesn’t do me much credit – and I’m not putting myself down – but I didn’t think the world was exactly waiting for another adult novel from me,” replies Burchill. “I had a No. 1 novel in 1989 but since then it’s been pretty much downhill. Also, inside me there’s no angst and no problems, and I think to write a great adult novel, like Graham Greene or Zoe Heller, you have to have a bit of angst inside you and I’ve reached a place in my life where I’m very happy and contented.” When she thought about attempting a teenage novel, Burchill was, she admits, delighted when she found out they were half the size of adult novels, ergo she wouldn’t have to “bang on for so long” and she also says she’d realised she hadn’t properly grown up. -

WBFSH Eventing Breeder 2020 (Final).Xlsx

LONGINES WBFSH WORLD RANKING LIST - BREEDERS OF EVENTING HORSES (includes validated FEI results from 01/10/2019 to 30/09/2020 WBFSH member studbook validated horses) RANK BREEDER POINTS HORSE (CURRENT NAME / BIRTH NAME) FEI ID BIRTH GENDER STUDBOOK SIRE DAM SIRE 1 J.M SCHURINK, WIJHE (NED) 172 SCUDERIA 1918 DON QUIDAM / DON QUIDAM 105EI33 2008 GELDING KWPN QUIDAM AMETHIST 2 W.H. VAN HOOF, NETERSEL (NED) 142 HERBY / HERBY 106LI67 2012 GELDING KWPN VDL ZIROCCO BLUE OLYMPIC FERRO 3 BUTT FRIEDRICH 134 FRH BUTTS AVEDON / FRH BUTTS AVEDON GER45658 2003 GELDING HANN HERALDIK XX KRONENKRANICH XX 4 PATRICK J KEARNS 131 HORSEWARE WOODCOURT GARRISON / WOODCOURT GARRISON104TB94 2009 MALE ISH GARRISON ROYAL FURISTO 5 ZG MEYER-KULENKAMPFF 129 FISCHERCHIPMUNK FRH / CHIPMUNK FRH 104LS84 2008 GELDING HANN CONTENDRO I HERALDIK XX 6 CAROLYN LANIGAN O'KEEFE 128 IMPERIAL SKY / IMPERIAL SKY 103SD39 2006 MALE ISH PUISSANCE HOROS 7 MME SOPHIE PELISSIER COUTUREAU, GONNEVILLE SUR127 MER TRITON(FRA) FONTAINE / TRITON FONTAINE 104LX44 2007 GELDING SF GENTLEMAN IV NIGHTKO 8 DR.V NATACHA GIMENEZ,M. SEBASTIEN MONTEIL, CRETEIL124 (FRA)TZINGA D'AUZAY / TZINGA D'AUZAY 104CS60 2007 MARE SF NOUMA D'AUZAY MASQUERADER 9 S.C.E.A. DE BELIARD 92410 VILLE D AVRAY (FRA) 122 BIRMANE / BIRMANE 105TP50 2011 MARE SF VARGAS DE STE HERMELLE DIAMANT DE SEMILLY 10 BEZOUW VAN A M.C.M. 116 Z / ALBANO Z 104FF03 2008 GELDING ZANG ASCA BABOUCHE VH GEHUCHT Z 11 A. RIJPMA, LIEVEREN (NED) 112 HAPPY BOY / HAPPY BOY 106CI15 2012 GELDING KWPN INDOCTRO ODERMUS R 12 KERSTIN DREVET 111 TOLEDO DE KERSER -

FROM BLOOD LIBEL to Boycott

FROM BLOOD LIBEL TO BOYCOTT CHANGING FACES OF BRITISH ANTISEMITISM Robert Wistrich he self-congratulatory and somewhat sanitized story of Anglo-Jewry since the mid- T 17th century “return” of the Jews to Britain traditionally depicted this history as a triumphal passage from servitude to freedom or from darkness to light. Great Britain— mother of parliaments, land of religious and civic toleration, cradle of the Industrial Revolution, and possessor of a great overseas empire had graciously extended its liberties to the Jewish community which had every reason to love Britain precisely because it was British. So if things had always been so good, how could they became so bad? Why are there so many dark clouds building up on the horizon? Why is Anglo-Jewry the only important ethnic or religious minority in contemporary Britain that has to provide a permanent system of guards and surveillance for its communal institutions, schools, synagogues, and cultural centers? Antisemitism in the British Isles is certainly not a new phenomenon. It has a long history which should surprise only those who naively think of the English as being a uniquely tolerant, fair-minded, and freedom-loving nation. There were periods like the 12th century, as the historian Anthony Julius recently noted, when Anglo-Jews were being injured or murdered without pity or conscience—at times in an atmosphere of public revelry. Over 150 people were killed in March 1190 during the massacre of the Jews of York. This nasty wave of violent persecution (which included the first anti-Jewish blood libel in Christian Europe) culminated in the unceremonious expulsion of Jewry in 1290. -

Online Questionnaires

Online Questionnaires Re-thinking Transgenderism The Trans Research Review • Understanding online trans communities. • Comprehending present-day transvestism. • Inconsistent definitions of ‘transgenderism’ and the connected terms. • !Information regarding • Transphobia. • Family matters with trans people. • Employment issues concerning trans people. • Presentations of trans people within media. The Questionnaires • ‘Male-To-Female’ (‘MTF’) transsexual people [84 questions] ! • ‘MTF’ transvestites/crossdressers/transgenderists [83 questions] ! • ‘Significant Others’ (Partners of trans people) [49 questions] ! • ‘Female To Male’ (‘FTM’) transsexual people [80 questions] ! • ‘FTM’ transvestites/crossdressers/transgenderists [75 questions] ! • ‘Trans Admirers’ (Individuals attracted to trans people) • [50 questions] The Questionnaires 2nd Jan. 2007 to ~ 12th Dec. 2010 on the international Gender Society website and gained 390,227 inputs worldwide ‘Male-To-Female’ transvestites/crossdressers/transgenderists: Being 'In the closet' - transgendered only in private or Being 'Out of the closet' - transgendered in (some) public places 204 ‘Female-To-Male’ transvestites/crossdressers/transgenderists: Being 'In the closet' - transgendered only in private or Being 'Out of the closet' - transgendered in (some) public places 0.58 1 - Understanding online trans communities. Transgender Support/Help Websites ‘Male-To-Female’ transvestites/crossdressers/transgenderists: (679 responses) Always 41 Often 206 Sometimes 365 Never 67 0 100 200 300 400 1 - Understanding -

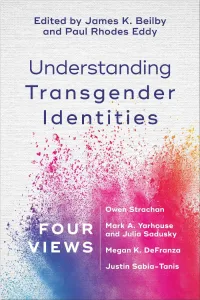

Understanding Transgender Identities

Understanding Transgender Identities FOUR VIEWS Edited by James K. Beilby and Paul Rhodes Eddy K James K. Beilby and Paul Rhodes Eddy, Understanding Transgender Identities Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2019. Used by permission. _Beilby_UnderstandingTransgender_BB_bb.indd 3 9/11/19 8:21 AM Contents Acknowledgments ix Understanding Transgender Experiences and Identities: An Introduction Paul Rhodes Eddy and James K. Beilby 1 Transgender Experiences and Identities: A History 3 Transgender Experiences and Identities Today: Some Issues and Controversies 13 Transgender Experiences and Identities in Christian Perspective 44 Introducing Our Conversation 53 1. Transition or Transformation? A Moral- Theological Exploration of Christianity and Gender Dysphoria Owen Strachan 55 Response by Mark A. Yarhouse and Julia Sadusky 84 Response by Megan K. DeFranza 90 Response by Justin Sabia- Tanis 95 2. The Complexities of Gender Identity: Toward a More Nuanced Response to the Transgender Experience Mark A. Yarhouse and Julia Sadusky 101 Response by Owen Strachan 131 Response by Megan K. DeFranza 136 Response by Justin Sabia- Tanis 142 3. Good News for Gender Minorities Megan K. DeFranza 147 Response by Owen Strachan 179 Response by Mark A. Yarhouse and Julia Sadusky 184 Response by Justin Sabia- Tanis 190 vii James K. Beilby and Paul Rhodes Eddy, Understanding Transgender Identities Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2019. Used by permission. _Beilby_UnderstandingTransgender_BB_bb.indd 7 9/11/19 8:21 AM viii Contents 4. Holy Creation, Wholly Creative: God’s Intention for Gender Diversity Justin Sabia- Tanis 195 Response by Owen Strachan 223 Response by Mark A. Yarhouse and Julia Sadusky 228 Response by Megan K. -

Terminology Packet

This symbol recognizes that the term is a caution term. This term may be a derogatory term or should be used with caution. Terminology Packet This is a packet full of LGBTQIA+ terminology. This packet was composed from multiple sources and can be found at the end of the packet. *Please note: This is not an exhaustive list of terms. This is a living terminology packet, as it will continue to grow as language expands. This symbol recognizes that the term is a caution term. This term may be a derogatory term or should be used with caution. A/Ace: The abbreviation for asexual. Aesthetic Attraction: Attraction to someone’s appearance without it being romantic or sexual. AFAB/AMAB: Abbreviation for “Assigned Female at Birth/Assigned Male at Birth” Affectionional Orientation: Refers to variations in object of emotional and sexual attraction. The term is preferred by some over "sexual orientation" because it indicates that the feelings and commitments involved are not solely (or even primarily, for some people) sexual. The term stresses the affective emotional component of attractions and relationships, including heterosexual as well as LGBT orientation. Can also be referred to as romantic orientation. AG/Aggressive: See “Stud” Agender: Some agender people would define their identity as not being a man or a woman and other agender people may define their identity as having no gender. Ally: A person who supports and honors sexual diversity, acts accordingly to challenge homophobic, transphobic, heteronormative, and heterosexist remarks and behaviors, and is willing to explore and understand these forms of bias within themself. -

Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Undergraduate Engineering Students: Perspectives, Resiliency, and Suggestions for Improving Engineering Education

AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF Andrea Evelyn Haverkamp for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Engineering presented on January 22, 2021. Title: Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Undergraduate Engineering Students: Perspectives, Resiliency, and Suggestions for Improving Engineering Education Abstract approved: ______________________________________________________ Michelle K. Bothwell Gender has been the subject of study in engineering education and science social research for decades. However, little attention has been given to transgender and gender nonconforming (TGNC) experiences or perspectives. The role of cisgender or gender conforming status has not been investigated nor considered in prevailing frameworks of gender dynamics in engineering. The overwhelming majority of literature in the field remains within a reductive gender binary. TGNC students and professionals are largely invisible in engineering education research and theory and this exclusion causes harm to individuals as well as our community as a whole. Such exclusion is not limited to engineering contexts but is found to be a central component of systemic TGNC marginalization in higher education and in the United States. This dissertation presents literature analysis and results from a national research project which uses queer theory and community collaborative feminist methodologies to record, examine, and share the diversity of experiences within the TGNC undergraduate engineering student community, and to further generate community-informed suggestions for increased support and inclusion within engineering education programs. Transgender and gender nonconforming participants and researchers were involved at every phase of the study. An online questionnaire, follow-up interviews, and virtual community input provided insight into TGNC experiences in engineering contexts, with relationships between race, gender, ability, and region identified. -

Book Stylebook on LGBTQ Terminology

nlgja: the association of lgbtq journalists stylestylebook onLGBTQterminology book NLGJA: The Association of LGBTQ Journalists is a journalist-led association working within the news media to advance fair and accurate coverage of LGBTQ communities and issues. We promote diverse and inclusive workplaces by holding the industry accountable and providing education, professional development and mentoring. Since its founding in 1990, the organization has grown to include more than 800 members and 25 chapter organizations, including 10 student chapters, in the United States. The NLGJA Stylebook on LGBTQ Terminology is intended to complement the prose stylebooks of individual publications, as well as The Associated Press Stylebook, the leading stylebook in U.S. newsrooms. It reflects the association’s mission of inclusive coverage of LGBTQ people, includes entries on words and phrases that have become common and features greater detail for earlier entries. The Stylebook will be continually updated and the latest version will always be available at www.nlgja.org/stylebook. 2120 L Street NW | Suite 850 | Washington, DC 20037 www.nlgja.org | [email protected] nlgja: the association of lgbtq journalists stylebook on LGBTQ terminology updated December 2020 stylebook Editors: Jeff McMillan and Sarah Blazucki Introduction This stylebook seeks to be a guide on language and terminology to help journalists cover LGBTQ subjects and issues with sensitivity and fairness, without bias or judgment. Because language is always changing, this guide is not definitive or fully inclusive. When covering the LGBTQ community, we encourage you to use the language and terminology your subjects use. They are the best source for how they would like to be identified. -

Slut Life , Exalted DLC/TCM

Slut Life , Exalted DLC/TCM "SFW" text-only edition You are an average mortal human, simply trying to carve yourself a place in Creation, same as everybody else. Well, you might not be all that average. Could you be a scavenger lord, sifting through the ruins of the First Age for magical Artifacts? Perhaps you’re an adventurer, experiencing as much of the beauty and danger of Creation as you can? Maybe you’re a simple Child of Earth after all, scratching a living from the soil, such as it is, and aspiring to nothing more than a good, simple, life. However exciting, or otherwise, you may be, you find yourself in Interesting times, indeed: Essence courses through your form, tearing apart your body, your mind, your very soul, and remaking you into something… else. You do not have the knowledge to describe what’s happening to you, even scavenger lords seldom know many secrets of the mystical wonders they unearth, but you can feel what the magic is turning you into: A sexual plaything, a living toy. There’s a glimmer of hope for you, though. The magic is powerful, true, but barely controlled. With a surge of willpower you somehow grasp the whipcord tendrils of uncontrolled energy, entering into a contest of wills over control over the spell. You might be able to mitigate the worst of the damage. Alternatively, you could try to claim the loosed magics and make them your own; at the cost of letting it work its way with you mind and body. Below are a series of options, some awarding influence, while others come at a cost. -

Child Sex Rings: a Behavioral Analysis for Criminal Justice Professionals Handling Cases of Child Sexual ~ Exploitation

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. NATIONAL CENTER FOR MISt.f9IN(. 1~"I"j('lrl'l~I) -----1.---' CHI L D R E N Child Sex Rings: A Behavioral Analysis For Criminal Justice Professionals Handling Cases of Child Sexual ~ Exploitation In cooperation with the Federal Bureau of Investigation ------------------ 149214 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been grantedNaElona1 by • center f'or Mlsslng . & Exploited Chi1dren/DOJ/FBI to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission of the copyright owner. Child Sex Rings: A Behavioral Analysis For Criminal Justice Professionals Handling Cases of Child Sexual Exploitation April 1992 Second Edition Kenneth V. Lanning Supervisory Special Agent Behavioral Science Unit Federal Bureau of Investigation FBI Academy Quantico, Virginia © National Center for Missing & Exploited Children Dedication This book is dedicated to the victims of child sex rings and to the memory of two FBI agents who devoted their professional lives to helping sexually exploited children. Leo E. Brunnick FBI Boston, Massachusetts Alan V. MacDonald FBI Boston, Massachusetts Contents Author's Preface v 1. Historical Overview 1 "Stranger Danger" 1 Intrafamilial Child Sexual Abuse 2 Return to "Stranger Danger" 2 The Acquaintance Molester 3 Satanism: A "New" Form of "Stranger Danger" 3 2. -

Comic Trans Presenting and Representing the Other in Stand-Up Comedy

2018 THESIS Comic Trans Presenting and Representing the Other in Stand-up Comedy JAMES LÓ RIEN MACDONALD LIVE ART AND PERFORMANCE STUDIES (LAPS) LIVE ART AND PERFORMANCE STUDIES (LAPS) 2018 THESIS Comic Trans Presenting and Representing the Other in Stand-up Comedy JAMES LÓ RIEN MACDONALD ABSTRACT Date: 22.09.2018 AUTHOR MASTER’S OR OTHER DEGREE PROGRAMME James Lórien MacDonald Live Art and Performance Studies (LAPS) NUMBER OF PAGES + APPENDICES IN THE TITLE OF THE WRITTEN SECTION/THESIS WRITTEN SECTION Comic Trans: Presenting and Representing the Other in 99 pages Stand- up Comedy TITLE OF THE ARTISTIC/ ARTISTIC AND PEDAGOGICAL SECTION Title of the artistic section. Please also complete a separate description form (for dvd cover). The artistic section is produced by the Theatre Academy. The artistic section is not produced by the Theatre Academy (copyright issues have been resolved). The final project can be The abstract of the final project can published online. This Yes be published online. This Yes permission is granted for an No permission is granted for an No unlimited duration. unlimited duration. This thesis is a companion to my artistic work in stand-up comedy, comprising artistic-based research and approaches comedy from a performance studies perspective. The question addressed in the paper and the work is “How is the body of the comedian part of the joke?” The first section outlines dominant theories about humour—superiority, relief, and incongruity—as a background the discussion. It touches on the role of the comedian both as untrustworthy, playful trickster, and parrhesiastes who speaks directly to power, backed by the truth of her lived experience.