Bordering the Mainstream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1955-12-16

... Servillg The State Iliversity of Iowa Camp« arullowa City Established in 1868~f'lv e Cents a Copy ~em~r of Associated Pr Wire and Wirephoto Service Iowa City. Jowa. Friday. Decem~r 16. 1955 All Eyes and Ears ~ ' ATO Lays Plans ISU'I Keeps Core For ·Radar System PARIS (JP)-Western statesmen decided Thursday to construct a • lIolfiM air raid warn in, screen from Norway acro" Europe to Tur ke.Y. backed by a new jam-proof communications net. , The United States will pay for the beginnlnll of thl Installation. Tbe foreign, finance and defense ministers of thc North Atlantic C:otJ"rse Revi slon Treaty Organization tOQk this step on an urient report form U.S. ~retary o( State John Foster ----- Vulles that the Soviet Union has I ( reopenoci the cold war. owa Tested Plan NATO's own military manners I'ly The Weather blclled Dulles with a warnin, that the Russian military threat Ex-Mayor Inlo Eftecl Is greater now than ever before. , 'tclal I. T"~ Dalb 1..... , Clear Tbe Soviets now have speedy jet WILMINGTON, Del. - Du Pont Company thu"day nnouneed a IT nt of more th n S9oo,OOO to over 100 unlversitles Ind colL , bombers capable of blasting any DileS at 72 rOt ~he n xt IC demlc year. & In September ,art of the NATO area with tre- UI is on of 20 universltie to r ive $1,~0 to be awarded io JDendous nuclear explosives. youn . r taC! m mbers of the ehemSatry department for r B, GENE INGLE work durin the summer of 1956. -

^Sehorse Junior Awmg British Breeders

s 8 4 THE NEW YORK HERALD>, SUNDAY, JUNE 18, 1922. ! AMAZING RECORDS <CYLLENE'S PLACE ILatest News and Gossip ARMY TO COMPETE MORVICH'S RIVALS OF A8TOR RACERS AS RACING SIRE' About the Horse Shows FOR POLO HONORS> IN $60,000RACE <$, ...... r.* ' s and Owners of Snob and BLUE FRONTf Jl Expatriated American His Descendants Predominate Press Agent's Occupation Is I Running Meetings Horses Players Arriving Pillory, the Man of the Hour in Turf Glassies Gone as Promoter of n * I 1 t <a nnn on I*>n£ Island to Train for Others Hopeful of Winning SALES Horseman England's to De neia m i f $^sehorse Junior Awmg British Breeders. This Season. Exhibits. PublicityCovington, Ky June (i-July 8 Championships. Kentucky Special. STABLESI IkW AUCTIONS Muntrcul, ( tin June bo(4 LEXINGTON Aqurdurl, N. Y Juno 10-July 7 24 Street Ty TP THIRD AVE. llnmUtun, Cun .June SU-July 3 rACTGKs IN THiF The prominence of the blocH of By G. CHAPLIN. I. Curt Krir. Cnu July 4-U About fifty polo horses will be Need of such a turf test as the 150,000 OLASSTCix I tankers, N. Y luty H-3U at »ije Mlneola fair grounds assembledon Kentucky Special, a scale weight race of "The Recognized Eastern Disbributkig Centre for Horses" ti.e winners and contoiaderaCyl!nof Tho scarcity of show horses la leading i Windsor, Can July 13-80 Island this week 15 Hnniiltun, Can July 31-Aug. 7 Uong for the use of one mile and a quarter, to be run next i he classic races in England this season to some queer practices this season In United States Army officers who are Saratoga. -

020.001: Collection of the Sisters of Our Lady of the Christian Doctrine

Guide to the Sisters of Our Lady of Christian Doctrine Collection Number 020.001 Guide to the Sisters of Our Lady of Christian Doctrine Collection Archives of the Archdiocese of New York Collection 020.001 Finding Aid Prepared by Ryan Frick Archives of the Archdiocese of New York St. Joseph’s Seminary 201 Seminary Avenue Yonkers, NY 10704 [email protected] 914-968-3200 x.8365 1 Last updated 11/03/17 Guide to the Sisters of Our Lady of Christian Doctrine Collection Number 020.001 Summary Information ____________________________________________________________________________ Creator: Sisters of Our Lady of Christian Doctrine Title: Sisters of Our Lady of Christian Doctrine Collection Date: 1849 - 2017 Extent: ____ linear feet (in # Hollinger box and # Paige box) Language: English, Italian, Latin Access Restrictions: Collection is open to researchers at the Archives of the Archdiocese of New York. Advance appointments are required for the use of archival materials. Preferred Citation: Published citations should take the following form: Identification of item, date (if known); Collection title, Collection Number; box number, folder number. Archives of the Archdiocese of New York, St. Joseph’s Seminary, Dunwoodie. Location of Related Materials: 2 Last updated 11/03/17 Guide to the Sisters of Our Lady of Christian Doctrine Collection Number 020.001 Biographical/Historical Note ____________________________________________________________________________ The Sisters of Our Lady of Christian Doctrine (RCD) were founded in 1910 by Mother Marianne of Jesus. The organization was founded with the primary goal of reaching European immigrants living in the Lower East Side of Manhattan. By the 1930s, the community had expanded to the Bronx, establishing a second settlement house called Ave Maria House. -

2020 International List of Protected Names

INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (only available on IFHA Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 03/06/21 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne-Billancourt, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org The list of Protected Names includes the names of : Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally renowned, either as main stallions and broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or jump) From 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf Since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf The main stallions and broodmares, registered on request of the International Stud Book Committee (ISBC). Updates made on the IFHA website The horses whose name has been protected on request of a Horseracing Authority. Updates made on the IFHA website * 2 03/06/2021 In 2020, the list of Protected -

Forest Glen Community

Engaging Chicago’s Diverse Communities in the Chicago Climate Action Plan COMMUNITY #7: FOREST GLEN Research Report Submitted by: Environment, Culture, and Conservation (ECCo), a Division of Science at The Field Museum To: The City of Chicago Department of Environment City of Chicago Richard M. Daley, Mayor Department of Environment 1 PROJECT OVERVIEW 22 COMMUNICATION AND DISSEMINATION 3 COMMUNITY OVERVIEW 25 CREATIVE MODELS FOR COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT 5 STAKEHOLDERS, PARTNERSHIPS, AND RELATIONSHIP-BUILDING 29 CONCLUSION CONTENTS 8 AWARENESS OF CLIMATE 30 COMMUNITY ASSET MAP CHANGE AND INTEREST IN ADDRESSING IT 32 REGIONAL ASSET MAP OF 13 COMMUNITY CONCERNS: SPRINGBOARDS FOR 34 OUR TEAM CLIMATE ACTION CITATIONS 19 ENVIRONMENTALLY-FRIENDLY TABLE PRACTICES, VALUES, AND TRADITIONS PARTICIPATING ORGANIZATIONS This research was commissioned by the Visit our Web site to download the Community and Regional Asset Maps, City of Chicago Department of Environment. and reports about other communities: http://fieldmuseum.org/climateaction Research was conducted by: Environment, Culture, and Conservation (ECCo), a Division of Science at The Field Museum with our partners: Sponsored by City of Chicago Department of Environment Sauganash Chamber of Commerce Sauganash Community Association November 2011 PROJECT OVERVIEW Engaging Chicago Communities in the Chicago Climate Action Plan - contrast racially and economically with most of the other research areas to date. Community #7: Forest Glen is the seventh community study commissioned Finally, the large proportion of single-family homes makes it a good area in by the City of Chicago Department of Environment (DOE) to identify strategies which to consider questions of homeowner participation in climate action, from for effectively engaging diverse communities throughout the city in the landscaping practices to energy retrofits. -

HEADLINE NEWS • 8/10/09 • PAGE 2 of 14

HEADLINE NEWS For information about TDN, call 732-747-8060. www.thoroughbreddailynews.com MONDAY, AUGUST 10, 2009 DOZEN-YATTA; CHAMP STILL PERFECT THE NEW SARATOGA Zenyatta (Street Cry {Ire}) had the closest scare of With a push for a stronger catalog and a renewed her perfect racing career, but came out on top to earn emphasis on customer service, Fasig-Tipton hopes to her 12th straight victory in yesterday=s GI Clement L further elevate the status of its Saratoga Selected Year- Hirsch H. at Del Mar. The magnificent dark bay mare ling Sale, which kicks off a two-night stand this eve- took up her usual position at the back of the seven- ning at 6 p.m. The fruits of its labors will soon be evi- horse field, well off the dent, but by all accounts, there has been a feeling of dawdling pace set by optimism and excitement in the days leading up to to- longshot Lethal Heat (Un- night=s opener. In the last few weeks, buyers com- usual Heat). Zenyatta was mented on the strength of the catalog on paper, and still last after six furlongs after perusing the wares over the weekend, several in 1:13.64 and fans who have confirmed that the individuals have lived up to came to see the champ their page. AAcross the roll to a 12th straight win board, I=ve heard nothing began to think jockey Mike but rave reviews,@ said Benoit Smith had left Zenyatta Taylor Made=s Mark Taylor. too much to do in the 1 1/16-mile race. -

To Consignors Hip Color & No

Index to Consignors Hip Color & No. Sex Sire Dam Dam's Sire Barn 46 Property of Adena Springs 4110 b. f. North Light (IRE) Rigorous Grand Slam 4115 b. f. North Light (IRE) Rocket Royale Roy 4128 ch. c. Alphabet Soup Scatter Buy Relaunch 4131 dk. b./br. c. Smart Strike Search the Church Holy Bull 4145 gr/ro. f. Giacomo Silent Majority Real Quiet 4149 ch. c. Golden Missile Siphonette Siphon (BRZ) 4166 ch. f. Macho Uno Sundown Delight Wild Rush 4188 dk. b./br. f. Ghostzapper Tina Dynamite Dynaformer 4190 gr/ro. c. Giacomo Tizprecious Jade Hunter 4217 ch. f. Awesome Again Winning Chance Alphabet Soup 4222 b. c. North Light (IRE) Worldly Pleasure Devil His Due 4241 b. f. North Light (IRE) Auburn Beauty Siphon (BRZ) 4249 b. f. Alphabet Soup Belle's Appeal Valid Appeal 4279 b. c. North Light (IRE) Cherry Brandy Golden Missile 4284 ch. c. Orientate Classy Cara General Meeting 4325 ch. f. Touch Gold Etamine Gone West 4326 gr/ro. f. Red Bullet Extra Holy Exploit 4343 dk. b./br. c. Milwaukee Brew Gist Cherokee Run 4346 b. c. Orientate Golden Candle King of Kings (IRE) 4384 b. c. Touch Gold Jade Eyed Friendly Lover 4394 dk. b./br. c. North Light (IRE) Lady Shari Judge T C 4395 gr/ro. f. Giacomo La Glitter Swain (IRE) 4411 dk. b./br. c. Fusaichi Pegasus Love and Marry Known Fact 4469 gr/ro. c. El Prado (IRE) Oxford Scholar Seeking the Gold 4474 dk. b./br. c. Touch Gold Party Maker Smart Strike Barn 2 Consigned by Ashview Farm LLC (Mr. -

OF PORTO RICO Jft.;

TJ. SUGAR-- 96 Degree 3. WEATHE2 EUESAU, MAY 30. Last 24 hours' rainfall, trace. Test Centrifugals, 3.45c.; Ter Ton, $63.00. 8S Temperature, Max. 82; Min. 73. Weather, fair. , Analysis Beets, 7s lQd; Per Ton, $73.60. ESTABLISHED JULV ?. 1356, VOL. XLIII., NO. 7429. HONOLULU, HAWAII TERRITORY. THURSDAY, MAY 31, 1906. PRICE FIVE CENTS. MEMORY OF UGAR R4 I PLANTERS BRAVE ftIE : !C VV - ;.V OF PORTO RICO Jft.;. --- ..nwV'v :x.i;'; vv . ) FACE V BIG STRIK DEAD ' m f Decoration Day Fittingly Several Cane Fields Are Burned, and the Situ- Observed by People ation Is Grave Because the American of Honolulu. Federation of Labor Aids the Strikers. - i" ftt-t- . fit i Veterans of the Civil "War. comrades Jr. r.? iA t tr' tSii George Y. i)e Long Post No. 45, (Associated Press Cablegrams.) Department of California anl Nevada, 1 ! .t-s- -I , Ik V I showing rank wearing badges their SAN JUAN, Porto Rico, May 31. Strikes of field workers are ind former army corps, gathered in l . having a sencus effect upon the sugar plantations, the situation be the little G. A. E. burial plot in Xuu-nt- i ing the more grave because the American Federation of Labor is Cemetery yesterday afternoon and i openly aiding the strikers. !id honor to the memory of their com- Several cane fields have been burned. rades turned under the little flower and ? " flag-bedeck- mounds. At the foot of I - is not Hawaii alone- - Wa?: - ? I It that has trouble with plantation laborers, but in the flagstaff", from which hung the rA these islands at least there has been no interference of the mainland labor organizations in troubles and Strines at half-mas- t, an old the that have arisen between the planters and their ritars iaborers. -

2008 International List of Protected Names

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities _________________________________________________________________________________ _ 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Avril / April 2008 Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : ) des gagnants des 33 courses suivantes depuis leur ) the winners of the 33 following races since their création jusqu’en 1995 first running to 1995 inclus : included : Preis der Diana, Deutsches Derby, Preis von Europa (Allemagne/Deutschland) Kentucky Derby, Preakness Stakes, Belmont Stakes, Jockey Club Gold Cup, Breeders’ Cup Turf, Breeders’ Cup Classic (Etats Unis d’Amérique/United States of America) Poule d’Essai des Poulains, Poule d’Essai des Pouliches, Prix du Jockey Club, Prix de Diane, Grand Prix de Paris, Prix Vermeille, Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe (France) 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Oaks, Derby, Ascot Gold Cup, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, St Leger, Grand National (Grande Bretagne/Great Britain) Irish 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Derby, Oaks, Saint Leger (Irlande/Ireland) Premio Regina Elena, Premio Parioli, Derby Italiano, Oaks (Italie/Italia) -

Enticed: a Special Addition to the Darley Stallion Roster

SATURDAY, DECEMBER 14, 2019 NEW PET SCAN UNVEILED AT SANTA ANITA ENTICED: A SPECIAL by Dan Ross "I think when we're done here, Santa Anita's going to have the ADDITION TO THE DARLEY most advanced and comprehensive availability of tools in the imaging realm of anywhere in the world." STALLION ROSTER These approbatory words, spoken by Craig Fravel, the freshly minted Chief Executive Officer, Racing Operations, at The Stronach Group (TSG), kicked off Friday's press conference heralding the recent arrival at Santa Anita of the Longmile Positron Emission Tomography (MILE-PET) Scan machine--a newly developed piece of equipment with two important burdens to shoulder. The first? Improve the early detection and diagnosis of potentially catastrophic injuries in racehorses. The other? Help rehabilitate the public image of a racetrack that has endured an Annus horribilis by any stretch of the imagination. Indeed, it was back in May, during the height of the welfare crisis, TSG announced that it had invested $500,000 to purchase by Katie Ritz the machine. Cont. p4 Medaglia d'Oro is the definitive flag-bearer at Darley's Jonabell Farm as their top-priced headliner since 2014. The Darley elite IN TDN EUROPE TODAY sire has 25 Grade I/Group 1 winners to his credit. This year, Darley welcomes a special new addition to the stallion barn. MARE OF THE MOMENT: REACTION Dual graded stakes winner Enticed is the first son of Medaglia Emma Berry profiles Reaction, the TDN Mare of the Moment, and dam of several successful hurdlers in Europe, including Envoi d'Oro bred and raced by Godolphin to stand at Darley. -

FEI 2016 Olympic Athlete-Horse Combination Ranking

FEI 2016 Olympic Athlete-Horse Combination Ranking - Jumping Final : Include events from 1.1.2015 to 06.03.2016 15 best results to count over the period of 1.1.2015 to 6.3.2016 Individual athletes (VEN, COL,PER,URU, TPE) or Athletes of nations already qualified (BRA, NED, FRA, USA, GER, SWE, CAN, ARG, QAT, UKR, JPN, AUS, SUI, GBR,ESP), are not included. NF Legend: Qualified / NOC already qualified with two Individuals or Individual has already qualified the NOC with another horse Rank Rider NFHorse Points 2 Luciana DINIZ POR B FIT FOR FUN 13 1450.00 7 Gregory WATHELET BEL B CONRAD DE HUS 1285.50 9 Abdelkebir OUADDAR MAR F QUICKLY DE KREISKER 1269.00 10 Emanuele GAUDIANO ITA B ADMARA 2 1245.00 12 Jérôme GUERY BEL B PAPILLON Z 1215.00 15 Bertram ALLEN IRL A MOLLY MALONE V 1187.69 26 Karim ELZOGHBY EGY F AMELIA 1104.00 27 Denis LYNCH IRL A ALL STAR 5 1092.50 32 Luciana DINIZ POR B WINNINGMOOD 1067.00 33 Bertram ALLEN IRL A ROMANOV 1065.00 53 Kamal Abdullah BAHAMDAN KSA F NOBLESSE DES TESS 936.50 55 Omer KARAEVLI TUR C DADJAK TER PUTTENEN 927.25 57 Piergiorgio BUCCI ITA B CASALLO Z 910.00 63 Ales OPATRNY CZE C ACOVARO 892.75 69 Bertram ALLEN IRL A QUIET EASY 4 855.00 73 Roberto TERAN TAFUR COL E WOKLAHOMA 844.75 76 Abdullah ALSHARBATLY KSA F DOMINGO 841.00 81 Gregory WATHELET BEL B EGANO VAN HET SLOGENHOF 821.00 86 Samuel PAROT CHI E ATLANTIS 802.75 87 Conor SWAIL IRL A VIVA COLOMBIA 802.50 90 Denis LYNCH IRL A ABBERVAIL VAN HET DINGESHOF 795.00 91 Emanuele GAUDIANO ITA B CASPAR 232 794.50 93 Carlos LOPEZ COL E PRINCE DE LA MARE 785.00 97 -

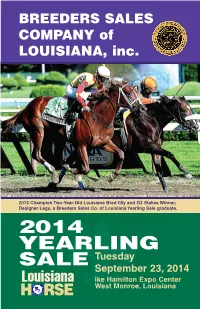

2014 Yearling

BREEDERS SALES COMPANY of LOUISIANA, inc. 2013 Champion Two-Year-Old Louisiana Bred filly and G2 Stakes Winner, Designer Legs, a Breeders Sales Co. of Louisiana Yearling Sale graduate. 2014 YEARLING SALE Tuesday September 23, 2014 Louisiana Ike Hamilton Expo Center HORSE West Monroe, Louisiana Designer Legs, a ‘12 Clear Creek Stud Consignment, wins the G2 Adirondack Stakes! PROVEN SUCCESS The Leading Louisiana YearLing Consignor ranked 1st an amazing 22 times in thirty years! Clear Creek stud has been the Leading Louisiana Yearling Consignor for the majority of the past thirty years, ranking either 1st or 2nd since 1984. The Clear Creek Stud Consignment has produced Stakes Winners of over $2.2 million in recent years, including G2SW Designer Legs, a 2012 sale graduate Our 2014 Consignment represents another outstanding group of individuals with excellent pedigrees and conformation. Visit us in person or at our web- site to see what we have to offer. With Yearlings by Clear Clear Stud Stallions B.J.’s Mark • CusToM for CarLos • haLf ours ide • Lion TaMer • oLe reBeL As well as Courageous Cat Majestic Warrior Paddy O’Prado Drosselmeyer Musket Man Parading High Cascade Porto Foricos Hold Me Back Northern Afleet Sidney’s Candy Lookin At Lucky Old Fashioned Tenpins Breeding • Boarding • Foaling & Mare Care • Breaking & Training • Sales Prep & Representation 11591 Hwy. 1078, Folsom, Louisiana 70437 985-796-5563 • Fax 985-796-3630 www.clearcreekstudllc.com e-mail: [email protected] spendthrift “The South’s Finest in Horse Transportation” A shipping agent is available for your convenience 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.