Authorial Anxiety in a Mass Media World: Four Modernists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why We Play: an Anthropological Study (Enlarged Edition)

ROBERTE HAMAYON WHY WE PLAY An Anthropological Study translated by damien simon foreword by michael puett ON KINGS DAVID GRAEBER & MARSHALL SAHLINS WHY WE PLAY Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Troop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com WHY WE PLAY AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL STUDY Roberte Hamayon Enlarged Edition Translated by Damien Simon Foreword by Michael Puett Hau Books Chicago English Translation © 2016 Hau Books and Roberte Hamayon Original French Edition, Jouer: Une Étude Anthropologique, © 2012 Éditions La Découverte Cover Image: Detail of M. C. Escher’s (1898–1972), “Te Encounter,” © May 1944, 13 7/16 x 18 5/16 in. (34.1 x 46.5 cm) sheet: 16 x 21 7/8 in. (40.6 x 55.6 cm), Lithograph. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9861325-6-8 LCCN: 2016902726 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by Te University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents Acknowledgments xiii Foreword: “In praise of play” by Michael Puett xv Introduction: “Playing”: A bundle of paradoxes 1 Chronicle of evidence 2 Outline of my approach 6 PART I: FROM GAMES TO PLAY 1. Can play be an object of research? 13 Contemporary anthropology’s curious lack of interest 15 Upstream and downstream 18 Transversal notions 18 First axis: Sport as a regulated activity 18 Second axis: Ritual as an interactional structure 20 Toward cognitive studies 23 From child psychology as a cognitive structure 24 . -

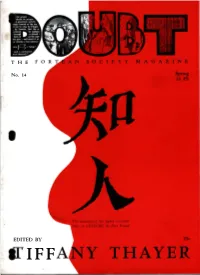

DOUBT Was Described "By Scientists" As Siderable Poet and Fire-Spouting Rebel

THE No. 14 EDITED BY IFF 202 203 PHILLY TARGET? made many forget that he was once a con observing their reactions. Funny - he never DOUBT was described "by scientists" as siderable poet and fire-spouting rebel. Early did see the similarity between himself and brilliant (bolide) in many years'' in life, he had sublime self-confidence and those monkeys. It never occurred to him T;h�· Fortean Society Magazine in the sky to the east of Philadel a grand ·impatience with all Philistines. that they had objections to being stuck with Because publishers could make no money Edited by TIFFANY THAYER phia "a few minutes after 3 o'clock thi� needles full of infection - for the good (10-21-45 from his books they rejected them, but of their jailors. But a beneficent god pass Secretary of tile old style) morning." Which re calls a similar occurrence on the morning of De Casseres had the courage to print them ing that way was not so blind as Dugan, FORTEAN SOCIETY 5-4-45 old style at 3:38. The May meteor himself, in the face of widespread popular and when he saw what the Conscientious Box 192 Grand Central Annex got much more publicity than this one in scorn for that practice. He employed no Objector was doing to the helpless monkey, "vanity publi�her", nor was his motive vain. New York City October, although judging from the above �e let a scratch admit the virus into Dugan's data it was the smaller of the two. Also - Read anything he wrote before 1925 to system - and kill him. -

Podolak Multifunctional Riverscapes

Multifunctional Riverscapes: Stream restoration, Capability Brown’s water features, and artificial whitewater By Kristen Nicole Podolak A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor G. Mathias Kondolf, Chair Professor Louise Mozingo Professor Vincent H. Resh Spring 2012 i Abstract Multifunctional Riverscapes by Kristen Nicole Podolak Doctor of Philosophy in Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning University of California, Berkeley Professor G. Mathias Kondolf, Chair Society is investing in river restoration and urban river revitalization as a solution for sustainable development. Many of these river projects adopt a multifunctional planning and design approach that strives to meld ecological, aesthetic, and recreational functions. However our understanding of how to accomplish multifunctionality and how the different functions work together is incomplete. Numerous ecologically justified river restoration projects may actually be driven by aesthetic and recreational preferences that are largely unexamined. At the same time river projects originally designed for aesthetics or recreation are now attempting to integrate habitat and environmental considerations to make the rivers more sustainable. Through in-depth study of a variety of constructed river landscapes - including dense historical river bend designs, artificial whitewater, and urban stream restoration this dissertation analyzes how aesthetic, ecological, and recreational functions intersect and potentially conflict. To explore how aesthetic and biophysical processes work together in riverscapes, I explored the relationship between one ideal of beauty, an s-curve illustrated by William Hogarth in the 18th century and two sets of river designs: 18th century river designs in England and late 20th century river restoration designs in North America. -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1955-12-16

... Servillg The State Iliversity of Iowa Camp« arullowa City Established in 1868~f'lv e Cents a Copy ~em~r of Associated Pr Wire and Wirephoto Service Iowa City. Jowa. Friday. Decem~r 16. 1955 All Eyes and Ears ~ ' ATO Lays Plans ISU'I Keeps Core For ·Radar System PARIS (JP)-Western statesmen decided Thursday to construct a • lIolfiM air raid warn in, screen from Norway acro" Europe to Tur ke.Y. backed by a new jam-proof communications net. , The United States will pay for the beginnlnll of thl Installation. Tbe foreign, finance and defense ministers of thc North Atlantic C:otJ"rse Revi slon Treaty Organization tOQk this step on an urient report form U.S. ~retary o( State John Foster ----- Vulles that the Soviet Union has I ( reopenoci the cold war. owa Tested Plan NATO's own military manners I'ly The Weather blclled Dulles with a warnin, that the Russian military threat Ex-Mayor Inlo Eftecl Is greater now than ever before. , 'tclal I. T"~ Dalb 1..... , Clear Tbe Soviets now have speedy jet WILMINGTON, Del. - Du Pont Company thu"day nnouneed a IT nt of more th n S9oo,OOO to over 100 unlversitles Ind colL , bombers capable of blasting any DileS at 72 rOt ~he n xt IC demlc year. & In September ,art of the NATO area with tre- UI is on of 20 universltie to r ive $1,~0 to be awarded io JDendous nuclear explosives. youn . r taC! m mbers of the ehemSatry department for r B, GENE INGLE work durin the summer of 1956. -

^Sehorse Junior Awmg British Breeders

s 8 4 THE NEW YORK HERALD>, SUNDAY, JUNE 18, 1922. ! AMAZING RECORDS <CYLLENE'S PLACE ILatest News and Gossip ARMY TO COMPETE MORVICH'S RIVALS OF A8TOR RACERS AS RACING SIRE' About the Horse Shows FOR POLO HONORS> IN $60,000RACE <$, ...... r.* ' s and Owners of Snob and BLUE FRONTf Jl Expatriated American His Descendants Predominate Press Agent's Occupation Is I Running Meetings Horses Players Arriving Pillory, the Man of the Hour in Turf Glassies Gone as Promoter of n * I 1 t <a nnn on I*>n£ Island to Train for Others Hopeful of Winning SALES Horseman England's to De neia m i f $^sehorse Junior Awmg British Breeders. This Season. Exhibits. PublicityCovington, Ky June (i-July 8 Championships. Kentucky Special. STABLESI IkW AUCTIONS Muntrcul, ( tin June bo(4 LEXINGTON Aqurdurl, N. Y Juno 10-July 7 24 Street Ty TP THIRD AVE. llnmUtun, Cun .June SU-July 3 rACTGKs IN THiF The prominence of the blocH of By G. CHAPLIN. I. Curt Krir. Cnu July 4-U About fifty polo horses will be Need of such a turf test as the 150,000 OLASSTCix I tankers, N. Y luty H-3U at »ije Mlneola fair grounds assembledon Kentucky Special, a scale weight race of "The Recognized Eastern Disbributkig Centre for Horses" ti.e winners and contoiaderaCyl!nof Tho scarcity of show horses la leading i Windsor, Can July 13-80 Island this week 15 Hnniiltun, Can July 31-Aug. 7 Uong for the use of one mile and a quarter, to be run next i he classic races in England this season to some queer practices this season In United States Army officers who are Saratoga. -

British Identity, the Masculine Ideal, and the Romanticization of the Royal Flying Corps Image

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2019 A Return to Camelot?: British Identity, The Masculine Ideal, and the Romanticization of the Royal Flying Corps Image Abby S. Whitlock College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Whitlock, Abby S., "A Return to Camelot?: British Identity, The Masculine Ideal, and the Romanticization of the Royal Flying Corps Image" (2019). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1276. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1276 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Return to Camelot?: British Identity, The Masculine Ideal, and the Romanticization of the Royal Flying Corps Image Abby Stapleton Whitlock Undergraduate Honors Thesis College of William and Mary Lyon G. Tyler Department of History 24 April 2019 Whitlock !2 Whitlock !3 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………….. 4 Introduction …………………………………….………………………………… 5 Chapter I: British Aviation and the Future of War: The Emergence of the Royal Flying Corps …………………………………….……………………………….. 13 Wartime Developments: Organization, Training, and Duties Uniting the Air Services: Wartime Exigencies and the Formation of the Royal Air Force Chapter II: The Cultural Image of the Royal Flying Corps .……….………… 25 Early Roots of the RFC Image: Public Imagination and Pre-War Attraction to Aviation Marketing the “Cult of the Air Fighter”: The Dissemination of the RFC Image in Government Sponsored Media Why the Fighter Pilot? Media Perceptions and Portrayals of the Fighter Ace Chapter III: Shaping the Ideal: The Early Years of Aviation Psychology .…. -

Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction

Andrew May Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction Editorial Board Mark Alpert Philip Ball Gregory Benford Michael Brotherton Victor Callaghan Amnon H Eden Nick Kanas Geoffrey Landis Rudi Rucker Dirk Schulze-Makuch Ru€diger Vaas Ulrich Walter Stephen Webb Science and Fiction – A Springer Series This collection of entertaining and thought-provoking books will appeal equally to science buffs, scientists and science-fiction fans. It was born out of the recognition that scientific discovery and the creation of plausible fictional scenarios are often two sides of the same coin. Each relies on an understanding of the way the world works, coupled with the imaginative ability to invent new or alternative explanations—and even other worlds. Authored by practicing scientists as well as writers of hard science fiction, these books explore and exploit the borderlands between accepted science and its fictional counterpart. Uncovering mutual influences, promoting fruitful interaction, narrating and analyzing fictional scenarios, together they serve as a reaction vessel for inspired new ideas in science, technology, and beyond. Whether fiction, fact, or forever undecidable: the Springer Series “Science and Fiction” intends to go where no one has gone before! Its largely non-technical books take several different approaches. Journey with their authors as they • Indulge in science speculation—describing intriguing, plausible yet unproven ideas; • Exploit science fiction for educational purposes and as a means of promoting critical thinking; • Explore the interplay of science and science fiction—throughout the history of the genre and looking ahead; • Delve into related topics including, but not limited to: science as a creative process, the limits of science, interplay of literature and knowledge; • Tell fictional short stories built around well-defined scientific ideas, with a supplement summarizing the science underlying the plot. -

1931 Article Titles and Notes Vol. III, No. 1, January 10, 19311

1931 article titles and notes Vol. III, No. 1, January 10, 19311 "'The Youngest' Proves Entertaining Production of Players' Club. Robert W. Graham Featured in Laugh Provoking Comedy; Unemployed to Benefit" (1 & 8 - AC, CO, CW, GD, and LA) - "Long ago it was decided that the chief aim of the Players' Club should be to entertain its members rather than to educate them or enlighten them on social questions or use them as an element in developing new ideas and methods in the Little Theatre movement."2 Philip Barry's "The Youngest" fit the bill very well. "Antiques, Subject of Woman's Club. Chippendale Furniture Discussed by Instructor at School of Industrial Art. Art Comm. Program" (1 - AE and WO) - Edward Warwick, an instructor at the Pennsylvania Museum School of Industrial Art, spoke to the Woman's Club on "The Chippendale Style in America." "Legion Charity Ball Jan. 14. Tickets Almost Sold Out for Benefit Next Friday Evening. Auxiliary Assisting" (1 & 4 - CW, LA, MO, SN, VM, and WO) - "What was begun as a Benefit Dance for the Unemployed has grown into a Charity Ball sponsored by the local America Legion Post with every indication of becoming Swarthmore's foremost social event of the year." The article listed the "patrons and patronesses" of the dance. Illustration by Frank N. Smith: "Proposed Plans for New School Gymnasium" with caption "Drawings of schematic plans for development of gymnasium and College avenue school buildings" (1 & 4 - BB, CE, and SC) - showed "how the 1.035 acres of ground just west of the College avenue school which was purchased from Swarthmore College last spring might be utilized for the enlargement of the present building into a single school plant." "Fortnightly to Meet on Monday" (1 - AE and WO) - At Mrs. -

Quentin Tarantino Retro

ISSUE 59 AFI SILVER THEATRE AND CULTURAL CENTER FEBRUARY 1– APRIL 18, 2013 ISSUE 60 Reel Estate: The American Home on Film Loretta Young Centennial Environmental Film Festival in the Nation's Capital New African Films Festival Korean Film Festival DC Mr. & Mrs. Hitchcock Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Howard Hawks, Part 1 QUENTIN TARANTINO RETRO The Roots of Django AFI.com/Silver Contents Howard Hawks, Part 1 Howard Hawks, Part 1 ..............................2 February 1—April 18 Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances ...5 Howard Hawks was one of Hollywood’s most consistently entertaining directors, and one of Quentin Tarantino Retro .............................6 the most versatile, directing exemplary comedies, melodramas, war pictures, gangster films, The Roots of Django ...................................7 films noir, Westerns, sci-fi thrillers and musicals, with several being landmark films in their genre. Reel Estate: The American Home on Film .....8 Korean Film Festival DC ............................9 Hawks never won an Oscar—in fact, he was nominated only once, as Best Director for 1941’s SERGEANT YORK (both he and Orson Welles lost to John Ford that year)—but his Mr. and Mrs. Hitchcock ..........................10 critical stature grew over the 1960s and '70s, even as his career was winding down, and in 1975 the Academy awarded him an honorary Oscar, declaring Hawks “a giant of the Environmental Film Festival ....................11 American cinema whose pictures, taken as a whole, represent one of the most consistent, Loretta Young Centennial .......................12 vivid and varied bodies of work in world cinema.” Howard Hawks, Part 2 continues in April. Special Engagements ....................13, 14 Courtesy of Everett Collection Calendar ...............................................15 “I consider Howard Hawks to be the greatest American director. -

Hunt, Stephen E. "'Free, Bold, Joyous': the Love of Seaweed in Margaret Gatty and Other Mid–Victorian Writers." Environment and History 11, No

The White Horse Press Full citation: Hunt, Stephen E. "'Free, Bold, Joyous': The Love of Seaweed in Margaret Gatty and Other Mid–Victorian Writers." Environment and History 11, no. 1 (February 2005): 5–34. http://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/3221. Rights: All rights reserved. © The White Horse Press 2005. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism or review, no part of this article may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, including photocopying or recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission from the publishers. For further information please see http://www.whpress.co.uk. ʻFree, Bold, Joyousʼ: The Love of Seaweed in Margaret Gatty and Other Mid-Victorian Writers STEPHEN E. HUNT Wesley House, 10 Milton Park, Redfield, Bristol, BS5 9HQ Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT With particular reference to Gattyʼs British Sea-Weeds and Eliotʼs ʻRecollections of Ilfracombeʼ, this article takes an ecocritical approach to popular writings about seaweed, thus illustrating the broader perception of the natural world in mid-Victorian literature. This is a discursive exploration of the way that the enthusiasm for seaweed reveals prevailing ideas about propriety, philanthropy and natural theology during the Victorian era, incorporating social history, gender issues and natural history in an interdisciplinary manner. Although unchaperoned wandering upon remote shorelines remained a questionable activity for women, ʻseaweedingʼ made for a direct aesthetic engagement with the specificity of place in a way that conforms to Barbara Gatesʼs notion of the ʻVictorian female sublimeʼ. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfihn master. UMI fihns the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter 6ce, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 A PEOPLE^S AIR FORCE: AIR POWER AND AMERICAN POPULAR CULTURE, 1945 -1965 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Steven Charles Call, M.A, M S. -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone.