The Technique of Copperplate Calligraphy: a Manual and Model Book of the Pointed Pen Method Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dubrovnik Manuscripts and Fragments Written In

Rozana Vojvoda DALMATIAN ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPTS WRITTEN IN BENEVENTAN SCRIPT AND BENEDICTINE SCRIPTORIA IN ZADAR, DUBROVNIK AND TROGIR PhD Dissertation in Medieval Studies (Supervisor: Béla Zsolt Szakács) Department of Medieval Studies Central European University BUDAPEST April 2011 CEU eTD Collection TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 7 1.1. Studies of Beneventan script and accompanying illuminations: examples from North America, Canada, Italy, former Yugoslavia and Croatia .................................................................................. 7 1.2. Basic information on the Beneventan script - duration and geographical boundaries of the usage of the script, the origin and the development of the script, the Monte Cassino and Bari type of Beneventan script, dating the Beneventan manuscripts ................................................................... 15 1.3. The Beneventan script in Dalmatia - questions regarding the way the script was transmitted from Italy to Dalmatia ............................................................................................................................ 21 1.4. Dalmatian Benedictine scriptoria and the illumination of Dalmatian manuscripts written in Beneventan script – a proposed methodology for new research into the subject .............................. 24 2. ZADAR MANUSCRIPTS AND FRAGMENTS WRITTEN IN BENEVENTAN SCRIPT ............ 28 2.1. Introduction -

Paläographie Der Neuzeit

Paläographie der Neuzeit: (traditionellerweise oft „Schriftenkunde der Neuzeit“). Früher typisch im Kanon der archivischen Fächer situiert als reines Hilfsmittel (Vermittlung von Lesefähigkeiten für die Lektüre frühneuzeitlicher Archivalien). Grundlegendes Problem der Literatur: es existieren zwar viele Überblicke zu „nationalen“ Schriftentwicklungen in den europäischen Ländern, aber kaum eine Übersicht über die Gesamtperspektive. Späte Verwissenschaftlichung nach dem Vorbild der Paläographie des Mittelalters erst im 20. Jahrhundert, zuvor polemische metawissenschaftliche Diskussion etwa zur Fraktur-Antiqua-Debatte. „Zweischriftigkeit“: Deutschsprachige Texte werden bis zur Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts immer in Kurrent (auch: Deutsche Schreibschrift) geschrieben, fremdsprachige Texte und Einschübe in deutschen Texten dagegen in aus dem humanistischen Schriftbereich abgeleiteten Schreibschriften. Grundsätzlich findet überall in Europa die Entwicklung der frühneuzeitlichen Schriften in zwei parallelen Bereichen statt: einerseits eine Weiterführung älterer spätgotischer Kursiven (mit teilweise charakteristischen „nationalen“ Einzelmerkmalen), andererseits eine Weiterentwicklung der aus Italien importierten humanistischen Kanzleischriften. In den einzelnen Regionen Europas wird dabei der „gotische“ Schriftstrang unterschiedlich früh oder spät auslaufen; am spätesten im deutschen Sprachraum (Kurrent als Schulausgangsschrift bis 1941 gelehrt). In der Frühen Neuzeit zunehmend dichte Publikation von gedruckten Schreibmeisterbüchern; diese ermöglichen -

Donald Jackson

Donald Jackson Calligrapher Artistic Director Donald Jackson was born in Lancashire, England in 1938 and is considered one of the world's foremost Western calligraphers. At the age of 13, he won a scholarship to art school where he spent six years studying drawing, painting, design and the traditional Western calligraphy and illuminating. He completed his post-graduate specialization in London. From an early age he sought to combine the use of the ancient techniques of the calligrapher's art with the imaginary and spontaneous letter forms of his own time. As a teenager his first ambition was to be "The Queen's Scribe" and a close second was to inscribe and illuminate the Bible. His talents were soon recognized. At the age of 20, while still a student himself, he was appointed a visiting lecturer (professor) at the Camberwell College of Art, London. Within six years he became the youngest artist calligrapher chosen to take part in the Victoria and Albert Museum's first International Calligraphy Show after the war and appointed a scribe to the Crown Office at the House of Lords. In other words, he became "The Queen's Scribe." Since then, in conjunction with a wide range of other calligraphic projects, he has continued to execute Historic Royal documents including Letters Patent under The Great Seal and Royal Charters. He was decorated by the Queen with the Medal of The Royal Victorian Order (MVO) which is awarded for personal services to the Sovereign in 1985. Jackson is an elected Fellow and past Chairman of the prestigious Society of Scribes and Illuminators, and in 1997, Master of 600-year-old Guild of Scriveners of the city of London. -

19Th Century Writing Activity: Pen &

Lesson Plan: #NoyesArtatHome 19th Century Writing Activity: Pen & Ink Activity based on letters on display in the Noyes Museum’s Estell Empire Exhibition For ages 12 & up Experience with cursive* writing not necessary Assistance from an adult would be helpful. Overview: Round Hand Script: This was the dominant cursive* writing style among 19th century writing “masters,” whose An account book from John Estell’s general store models were engraved on metal. Letters Circa 1836 – 1837 sloped to the right, and thick lines were © Collection of Stockton University produced on the downstrokes using a flexible, straight-edged (not pointed) pen nib (tip). Thin lines were made by using the corner of the nib. Round hand included decorative swirls referred to as “command of hand.” Copperplate: This type of writing was made with a flexible, pointed metal pen. Copperplate script differs from round hand in the gradual swelling of the broad strokes on curved forms and the narrowness of the backstrokes of b, e, and o. Definitions from Britannica.com: https://www.britannica.com/topic/black-letter Project Description: This lesson provides a brief overview of handwriting in the 19th century and a hands-on writing activity. First, paint with a teabag to make “old” looking paper. To write, use a quill** pen with black ink or watered-down paint, or a marker. Try to read and copy the example of 19th century writing. Can you write your own name, or a whole letter to a friend? Supplies: 8.5 x 11” piece of paper A tea bag; preferably a darker tea such as black tea (Lipton, Red Rose) A watercolor brush Your choice of: a quill** pen and black ink, watered-down black paint with a fine-tipped brush, or a black marker (for example: Crayola – “broad line” or Sharpie – “fine point,” the newer, the better) *Cursive writing is a style of writing in which all of the letters in a word are connected. -

Writing As Material Practice Substance, Surface and Medium

Writing as Material Practice Substance, surface and medium Edited by Kathryn E. Piquette and Ruth D. Whitehouse Writing as Material Practice: Substance, surface and medium Edited by Kathryn E. Piquette and Ruth D. Whitehouse ]u[ ubiquity press London Published by Ubiquity Press Ltd. Gordon House 29 Gordon Square London WC1H 0PP www.ubiquitypress.com Text © The Authors 2013 First published 2013 Front Cover Illustrations: Top row (from left to right): Flouda (Chapter 8): Mavrospelio ring made of gold. Courtesy Heraklion Archaelogical Museum; Pye (Chapter 16): A Greek and Latin lexicon (1738). Photograph Nick Balaam; Pye (Chapter 16): A silver decadrachm of Syracuse (5th century BC). © Trustees of the British Museum. Middle row (from left to right): Piquette (Chapter 11): A wooden label. Photograph Kathryn E. Piquette, courtesy Ashmolean Museum; Flouda (Chapter 8): Ceramic conical cup. Courtesy Heraklion Archaelogical Museum; Salomon (Chapter 2): Wrapped sticks, Peabody Museum, Harvard. Photograph courtesy of William Conklin. Bottom row (from left to right): Flouda (Chapter 8): Linear A clay tablet. Courtesy Heraklion Archaelogical Museum; Johnston (Chapter 10): Inscribed clay ball. Courtesy of Persepolis Fortification Archive Project, Oriental Institute, University of Chicago; Kidd (Chapter 12): P.Cairo 30961 recto. Photograph Ahmed Amin, Egyptian Museum, Cairo. Back Cover Illustration: Salomon (Chapter 2): 1590 de Murúa manuscript (de Murúa 2004: 124 verso) Printed in the UK by Lightning Source Ltd. ISBN (hardback): 978-1-909188-24-2 ISBN (EPUB): 978-1-909188-25-9 ISBN (PDF): 978-1-909188-26-6 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/bai This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. -

National Diploma in Calligraphy Helpful Hints for FOUNDATION Diploma Module A

National Diploma in Calligraphy Helpful hints for FOUNDATION Diploma Module A THE LETTERFORM ANALYSIS “In A4 format make an analysis of the letter-forms of an historical manuscript which reflects your chosen basic hand. Your analysis should include x-height, letter formation and construction, heights of ascenders and descenders, etc. This can be in the form of notes added to enlarged photocopies of a relevant historical manuscript, together with your own lettering studies” At this first level, you will be working with one basic hand only and its associated capitals. This will be either Foundational (Roundhand) in which case study the Ramsey Psalter, or Formal Italic, where you can study a hand by Arrighi or Francisco Lucas, or other fine Italian scribe. Find enlarged detailed illustrations from ‘Historical Scripts by Stan Knight, or A Book of Scripts, by A Fairbank, or search the internet. Stan Knight’s book is the ‘bible’ because the enlargements are clear and at least 5mm or larger body height – this is the ideal. Show by pencil lines & measurements on the enlargement how you have worked out the pen angle, nib-widths, ascender & descender heights and shape of O, arch formations etc, use a separate sheet to write down this information, perhaps as numbered or bullet points, such as: 1. Pen angle 2. 'x'height 3. 'o'form 4, 5,6 Number of strokes to each letter, their order, direction: - make a general observation, and then refer the reader to the alphabet (s) you will have written (see below), on which you will have added the stroke order and directions to each letter by numbered pencil arrows. -

Vaikuntha Children.) Methods from Each of These Large Categories Can Be Combined to Create Many Specific Ways to Teach

Please Read This First This book is for teachers, parents, ISKCON leaders, students, and anyone interested in conscious education. Here we are neither presenting a blueprint for a traditional gurukula nor what you probably feel a curriculum should be after reading Çréla Prabhupäda’s instructions. It is an adaptation for our present needs in Western countries. Certainly, what we suggest is not the only way but if you’re starting and don’t know what to do, we hope to be of help. For veteran educators, there are many ideas and resources which can enhance your service. Because we are now using mostly non- devotee teaching materials, the amount of Kåñëa consciousness being taught depends upon the individual teachers. Kåñëa consciousness is not intrinsic in these curriculum guidelines but we have tried to select the most efficient and least harmful methods and materials which should make the injection of spiritual principles easiest. By following the guidelines suggested here, you can be reasonably assured that you will meet all legal requirements, have a complete curriculum, and that the students will get a good education. Although this book follows a logical order from beginning to end, you can skip through and pick what is of most value to you. Additionally, a lot of important material can be found in the appendixes. New educational material is constantly being produced. Suppliers come and go. Therefore, some of this information is dated. Please update your copy of this guidebook regularly. We have included some quotes from Çréla Prabhupäda, called “drops of nectar,” at the beginning of most chapters. -

Detecting Forgery: Forensic Investigation of Documents

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Legal Studies Social and Behavioral Studies 1996 Detecting Forgery: Forensic Investigation of Documents Joe Nickell University of Kentucky Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Nickell, Joe, "Detecting Forgery: Forensic Investigation of Documents" (1996). Legal Studies. 1. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_legal_studies/1 Detecting Forgery Forensic Investigation of DOCUlllen ts .~. JOE NICKELL THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 1996 byThe Universiry Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2005 The Universiry Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine Universiry, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky Universiry, The Filson Historical Sociery, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Sociery, Kentucky State University, Morehead State Universiry, Transylvania Universiry, University of Kentucky, Universiry of Louisville, and Western Kentucky Universiry. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales qtJices:The Universiry Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows: Nickell,Joe. Detecting forgery : forensic investigation of documents I Joe Nickell. p. cm. ISBN 0-8131-1953-7 (alk. paper) 1. Writing-Identification. 2. Signatures (Writing). 3. -

A New Look at Vietnamese Female Immigrant's Social

International Journal of Academic Research and Reflection Vol. 4, No. 7, 2016 ISSN 2309-0405 A NEW LOOK AT VIETNAMESE FEMALE IMMIGRANT’S SOCIAL ADAPTATION: INTEGRATED VIETNAM CULTURE AND ART WITHIN SCHOOLS Chou, Mei-Ju Assistant Professor, Early Childhood Education Department, National Pingtung University, TAIWAN, R. O. C. ABSTRACT With advent of internationalization, among the new immigrant groups, new immigrant females in Taiwan show a new pattern called “innovative adapters” by this research. This research aims to discuss the issues relative to a new Vietnamese immigrant female in order to further understand the new immigrant females who leave their hometown due to marriage relationship, and who experience the cultural adaptation following another life career in the immigrant country. This research adopted case study method, and started with representing the case’s life story through narrative method to focus on the issue for understanding her inner conflict in the process of cultural identity and social adaptation. Then, with guidance project supported by spiritual support from family members, activity design scaffold discussed by school teachers together, and resource assistance from juridical persons, the new immigrant female was encouraged to walk into the campus and classroom of her two children. She was also encouraged to share Vietnamese culture, art, music, and drama with children. In order to understand the activity process, problem solution strategy’s drawing up and retrospection, this research tackled with the original data, applied to videos and recordings, collected each detailed record and unstructured interview carefully with participant observation. Data gathered in the study is qualitative, and the tools were used systematically and properly to collect data, including surveys, interviews, documentation review, observation, and the collection of children’s art work. -

Paläographie Einzelne Schriftarten Neuzeitliche Schriften

Thomas Frenz: Bibliographie zur Diplomatik und verwandten Fachgebieten der Historischen Hilfswissenschaften mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Papsturkunden Paläographie einzelne Schriftarten neuzeitliche Schriften Atelier du Centre Généalogique de Touraine (Hg.): Introduction à la Paléographie, o.O.o.J. Bernhard Bischoff: Lettera mercantesca. In: Lexikon des gesamten Buchwesens, 2. Aufl., IV 506 Bernhard Bischoff: Mercantesca. In: Lexikon des gesamten Buchwesens, 2. Aufl., V 146 H. Buske: Deutsche Schrift. In: Lexikon des gesamten Buchwesens, 2. Aufl., II 263-265 H. Buske: Rounde hand. In: Lexikon des gesamten Buchwesens, 2. Aufl., VI 391 Lewis F. Day: Penmanship of the XVI, XVII, and XVIII Centuries T. N. Tacenko: U^cebniki pi^sma kak isto^cnik po istorii n^emeckogo kursiva XVI - XVII vv., Srednije veka 42()157-181 Th. Frenz: Secretary Hand. In: Lexikon des gesamten Buchwesens, 2. Aufl., VII 41 Thomas Frenz: Bollatica. In: Lexikon des gesamten Buchwesens, 2. Aufl., I 496 Thomas Frenz: Kanzleikurrent. In: Lexikon des gesamten Buchwesens, 2. Aufl., IV 152 Thomas Frenz: Kanzleischrift. In: Lexikon des gesamten Buchwesens, 2. Aufl., IV 152f. W. Milde: Retondilla (Redondilla). In: Lexikon des gesamten Buchwesens, 2. Aufl., VI 282 L. Strahlendorf: Die Entwicklung der Schrift und des Schreibunterichts in der neueren und neuesten Zeit, Berlin 1866 A. Bourmont: Manuel de paléographie des XVI - XVIII siècles, Caen 1881 Ficker, J. /Winckelmann: Handschriftenproben des sechzehnten Jahrhunderts nach Straßburger Originalen, Straßburg 1902 Stein, -

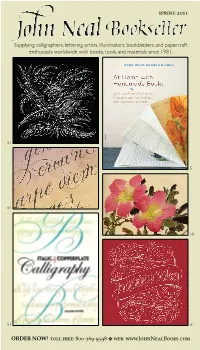

Spring 2011 Supplying Calligraphers, Lettering Artists, Illuminators

spring 2011 Supplying calligraphers, lettering artists, illuminators, bookbinders and papercraft enthusiasts worldwide with books, tools, and materials since 1981. 61 5 64 50 61 61 ORDER NOW! toll free: 800-369-9598 v web: www.JohnNealBooks.com Julie Eastman. B&L 8.2 “...an informative, engaging, Bill Waddington. B&L 8.2 and valued resource.” Need something new to inspire you? –Ed Hutchins Subscribe to Bound & Lettered and have each issue – filled with practical information on artists’ books, bookbinding, calligraphy and papercraft – delivered to your mailbox. Bound & Lettered features: how-to articles with helpful step-by-step instructions and illustrations, artist galleries featuring the works of accomplished calligraphers & book artists, useful articles on tools & materials, and book & exhibit reviews. You will find each issue filled with wonderful ideas and projects. Subscribe today! Annie Cicale. B&L 8.3 Every issue of Bound & Lettered has articles full of practical information for calligraphers, bookbinders and book artists. Fran Watson. B&L 8.3 Founded by Shereen LaPlantz, Bound & Lettered is a quarterly magazine of calligraphy, bookbinding and papercraft. Published by John Neal, Bookseller. Now with 18 color pages! Subscription prices: USA Canada Others Four issues (1 year) $26 $34 USD $40 USD Eight issues (2 years) $47 $63 USD $75 USD 12 issues (3 years) $63 $87 USD $105 USD mail to: Bound & Lettered, 1833 Spring Garden St., First Floor, Sue Bleiwess. B&L 8.2 Greensboro, NC 27403 b SUBSCRIBE ONLINE AT WWW .JOHNNEALBOOKS .COM B3310. Alphabeasties and Other Amazing Types by Sharon Werner and Sarah Forss. 2009. 56pp. 9"x11.5". -

George Bickhams Penmanship Made Easy Or the Young Clerks Assistant Pdf, Epub, Ebook

GEORGE BICKHAMS PENMANSHIP MADE EASY OR THE YOUNG CLERKS ASSISTANT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK George Bickham | 64 pages | 21 Jan 1998 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486297798 | English | New York, United States George Bickhams Penmanship Made Easy or the Young Clerks Assistant PDF Book Illustration Art. Add links. Learning to write Spencerian script. George Bickham the Elder was born near the end of the seventeenth century. July 13, at am. For what was meant to be a practical form of business handwriting, the round-hand scripts displayed in The Universal Penman feature a surprising number of flamboyant flourishes and decorative extensions. A complete volume of The Universal Penman published in London in might cost a few thousand dollars or more. Folio , detail. Prints and Multiples. American Fine Art. This was the work of George Bickham, a calligrapher and engraver who in took on the task of inviting the best scribes of his day to contribute examples of their finest handwriting, which would be engraved, published, and sold to subscribers as a series of 52 parts over a period of eight years. Collecting The specimen illustrates the beautiful flowing shaded letterforms based on ovals that typify this style of script. In the 18th century, writing masters taught handwriting to educated men and women, especially to men who would be expected to use it on a daily basis in commerce. Kelchner, He is Director of the Scripta Typographic Institute. A wonderful example of this script, penned by master penman HP Behrensmeyer is shown in Sample 4. Studio handbook : lettering : over pages, lettering, design and layouts, new alphabets.