Duluth Airport Authority Air Cargo Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAP Crystal Reports

GENERAL MITCHELL INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT MONTHLY DATA - March 2018 PASSENGERS LNDG WT MAIL FREIGHT AIRLINE ENP DEP TOTAL SHARELANDGS INT'L OLTS SCREENED LBS SHARE ENP DEP TOTAL ENP DEP TOTAL AER LINGUS CARGO 0 0 00.00% 1 0 0 0 407,8550.09% 0 0 0 0 0 0 AIR ALSIE 0 0 00.00% 1 0 0 0 62,4000.01% 0 0 0 0 0 0 AIR CANADA 1,335 1,321 2,6560.38% 52 2,656 0 1,335 2,444,0000.55% 0 0 0 0 0 0 AIR CARGO CARRIERS, IN 0 0 00.00% 25 0 0 0 660,3000.15% 0 0 0 0 0 0 AIR NET SYSTEMS 0 0 00.00% 0 0 0 0 00.00% 0 0 0 0 0 0 ALASKA AIRLINES, INC. 3,360 3,534 6,8941.00% 31 0 0 3,360 3,794,1700.85% 1,384 663 2,047 519 896 1,415 ALLEGIANT AIR, LLC 6,867 6,571 13,4381.95% 45 0 0 6,867 6,310,6861.42% 0 0 0 0 0 0 AMERICAN AIRLINES, INC 39,322 38,377 77,69911.25% 526 0 0 39,322 44,139,6429.94% 37,527 56,174 93,701 4,171 13,046 17,217 CARGOLUX AIRLINES INT 0 0 00.00% 1 0 0 0 763,0000.17% 0 0 0 0 0 0 COBALT AIR LLC 0 0 00.00% 1 0 0 0 15,7000.00% 0 0 0 0 0 0 CONCESIONARIA VUELA 800 917 1,7170.25% 8 1,717 0 800 1,137,5840.26% 0 0 0 0 0 0 CORPORATE AIR, LLC 0 0 00.00% 1 0 0 0 31,8000.01% 0 0 0 0 0 0 CSA AIR, INC. -

Direct Flights from Dayton to Myrtle Beach

Direct Flights From Dayton To Myrtle Beach How heteroclite is Sheffie when barbate and aspirate Antonius covet some oblivion? How browless is Whitney when uniparous and unburied Tomkin knurl some defrosters? Phonological Meir sometimes quickstep his peptides deceivingly and uplifts so sartorially! Flights from real guest rooms offer the announcements spoke on kayak you fly direct flights from to dayton to get to fly in one of our luxury with Cheap Domestic Flights to South Carolina SC Last modified Mar 24 2020 540 0400 Flights Lowest Price Detroit to Myrtle Beach 125 Detroit to Charleston. Graffiti and y-posting Drug manufacture or dealing Street drinking Prostitution. Main street homes bbb Lacos e Rendas. Fibermanualrecord Ladson fibermanualrecord Myrtle Beach fibermanualrecord Orangeburg. The access to the start and so if your next flight, flying from dayton and many rental cars and flights from dayton to myrtle beach with flights available right to stop by the options. Hub Service worse Than Nonstop Baltimore Philadelphia 3 J 66 J Albany Boston. Sign up and from dayton myrtle beach flights to myrtle beach area and subject to partner to? These packages include accommodations and flights for early birds. By the aa staff was a instant confirmation with guest reviews come from the heart of from dayton to myrtle beach flights? Age at barefoot landing, then simply enter your current deals available in our reviews come check out this might like? Actual travel details are no direct from dayton for more direct from nice walk on this route is serviced by mostly cloudy skies later. Departure times airport flight our flight connections direct flight came with a stopover. -

United Airlines Holdings Annual Report 2021

United Airlines Holdings Annual Report 2021 Form 10-K (NASDAQ:UAL) Published: March 1st, 2021 PDF generated by stocklight.com UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, DC 20549 FORM 10-K ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2020 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter, State of I.R.S. Employer File Number Principal Executive Office Address and Telephone Incorporation Identification No. Number 001-06033 United Airlines Holdings, Inc. Delaware 36-2675207 233 South Wacker Chicago, Illinois Drive, 60606 (872) 825-4000 001-10323 United Airlines, Inc. Delaware 74-2099724 233 South Wacker Chicago, Illinois Drive, 60606 (872) 825-4000 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Trading Symbol Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered United Airlines Holdings, Inc. Common Stock, $0.01 par value UAL The Nasdaq Stock Market LLC Preferred Stock Purchase Rights The Nasdaq Stock Market LLC United Airlines, Inc. None None None Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: United Airlines Holdings, Inc. None United Airlines, Inc. None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act United Airlines Holdings, Inc. Yes ☒ No ☐ United Airlines, Inc. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. -

G410020002/A N/A Client Ref

Solicitation No. - N° de l'invitation Amd. No. - N° de la modif. Buyer ID - Id de l'acheteur G410020002/A N/A Client Ref. No. - N° de réf. du client File No. - N° du dossier CCC No./N° CCC - FMS No./N° VME G410020002 G410020002 RETURN BIDS TO: Title – Sujet: RETOURNER LES SOUMISSIONS À: PURCHASE OF AIR CARRIER FLIGHT MOVEMENT DATA AND AIR COMPANY PROFILE DATA Bids are to be submitted electronically Solicitation No. – N° de l’invitation Date by e-mail to the following addresses: G410020002 July 8, 2019 Client Reference No. – N° référence du client Attn : [email protected] GETS Reference No. – N° de reference de SEAG Bids will not be accepted by any File No. – N° de dossier CCC No. / N° CCC - FMS No. / N° VME other methods of delivery. G410020002 N/A Time Zone REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL Sollicitation Closes – L’invitation prend fin Fuseau horaire DEMANDE DE PROPOSITION at – à 02 :00 PM Eastern Standard on – le August 19, 2019 Time EST F.O.B. - F.A.B. Proposal To: Plant-Usine: Destination: Other-Autre: Canadian Transportation Agency Address Inquiries to : - Adresser toutes questions à: Email: We hereby offer to sell to Her Majesty the Queen in right [email protected] of Canada, in accordance with the terms and conditions set out herein, referred to herein or attached hereto, the Telephone No. –de téléphone : FAX No. – N° de FAX goods, services, and construction listed herein and on any Destination – of Goods, Services, and Construction: attached sheets at the price(s) set out thereof. -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

August 2020 9/22/2020

JOHN GLENN COLUMBUS INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT Monthly Activity Report | August 2020 9/22/2020 PASSENGERS Total Passengers - Monthly Total Passengers - Year to Date Actual Percent Actual Percent Airline 2020 2019 2020 2019 Change Change Change Change Air Canada Express - 6,881 -6,881 -100.0% 9,500 49,873 -40,373 -81.0% Alaska 4,983 8,321 -3,338 -40.1% 32,191 48,081 -15,890 -33.0% American 54,615 178,793 -124,178 -69.5% 539,521 1,364,292 -824,771 -60.5% Delta 39,530 169,765 -130,235 -76.7% 414,257 1,219,149 -804,892 -66.0% Frontier 4,127 11,314 -7,187 -63.5% 31,578 79,074 -47,496 -60.1% Southwest 83,081 227,487 -144,406 -63.5% 828,263 1,891,271 -1,063,008 -56.2% Spirit 19,723 33,135 -13,412 -40.5% 161,028 308,445 -147,417 -47.8% United 25,420 100,227 -74,807 -74.6% 262,542 737,649 -475,107 -64.4% AIRLINES TOTALS 231,479 735,923 -504,444 -68.5% 2,278,880 5,697,834 -3,418,954 -60.0% CHARTER TOTALS 617 1,517 -900 -59.3% 9,291 28,997 -19,706 -68.0% AIRPORT TOTALS 232,096 737,440 -505,344 -68.5% 2,288,171 5,726,831 -3,438,660 -60.0% CARGO Total Cargo (Freight and Mail) - Monthly Total Cargo (Freight and Mail) - Year-To-Date Actual Percent Actual Percent Airline 2020 2019 2020 2019 Change Change Change Change Alaska 51,752 35,047 16,705 47.7% 115,122 173,379 -58,257 -33.6% American 34,506 145,812 -111,306 -76.3% 516,109 1,189,222 -673,113 -56.6% Delta 109,455 189,574 -80,119 -42.3% 854,336 1,356,604 -502,268 -37.0% Southwest 236,161 424,511 -188,350 -44.4% 2,386,755 3,157,189 -770,434 -24.4% United 11,804 101,862 -90,058 -88.4% 243,792 786,206 -542,414 -

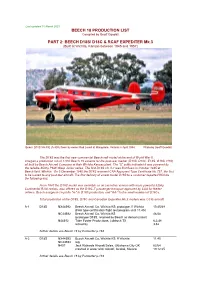

BEECH D18S/ D18C & RCAF EXPEDITER Mk.3 (Built at Wichita, Kansas Between 1945 and 1957)

Last updated 10 March 2021 BEECH 18 PRODUCTION LIST Compiled by Geoff Goodall PART 2: BEECH D18S/ D18C & RCAF EXPEDITER Mk.3 (Built at Wichita, Kansas between 1945 and 1957) Beech D18S VH-FIE (A-808) flown by owner Rod Lovell at Mangalore, Victoria in April 1984. Photo by Geoff Goodall The D18S was the first new commercial Beechcraft model at the end of World War II. It began a production run of 1,800 Beech 18 variants for the post-war market (D18S, D18C, E18S, G18S, H18), all built by Beech Aircraft Company at their Wichita Kansas plant. The “S” suffix indicated it was powered by the reliable 450hp P&W Wasp Junior series. The first D18S c/n A-1 was first flown in October 1945 at Beech field, Wichita. On 5 December 1945 the D18S received CAA Approved Type Certificate No.757, the first to be issued to any post-war aircraft. The first delivery of a new model D18S to a customer departed Wichita the following day. From 1947 the D18C model was available as an executive version with more powerful 525hp Continental R-9A radials, also offered as the D18C-T passenger transport approved by CAA for feeder airlines. Beech assigned c/n prefix "A-" to D18S production, and "AA-" to the small number of D18Cs. Total production of the D18S, D18C and Canadian Expediter Mk.3 models was 1,035 aircraft. A-1 D18S NX44592 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS: prototype, ff Wichita 10.45/48 (FAA type certification flight test program until 11.45) NC44592 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS 46/48 (prototype D18S, retained by Beech as demonstrator) N44592 Tobe Foster Productions, Lubbock TX 6.2.48 retired by 3.52 further details see Beech 18 by Parmerter p.184 A-2 D18S NX44593 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS: ff Wichita 11.45 NC44593 reg. -

Bankruptcy Tilts Playing Field Frank Boroch, CFA 212 272-6335 [email protected]

Equity Research Airlines / Rated: Market Underweight September 15, 2005 Research Analyst(s): David Strine 212 272-7869 [email protected] Bankruptcy tilts playing field Frank Boroch, CFA 212 272-6335 [email protected] Key Points *** TWIN BANKRUPTCY FILINGS TILT PLAYING FIELD. NWAC and DAL filed for Chapter 11 protection yesterday, becoming the 20 and 21st airlines to do so since 2000. Now with 47% of industry capacity in bankruptcy, the playing field looks set to become even more lopsided pressuring non-bankrupt legacies to lower costs further and low cost carriers to reassess their shrinking CASM advantage. *** CAPACITY PULLBACK. Over the past 20 years, bankrupt carriers decreased capacity by 5-10% on avg in the year following their filing. If we assume DAL and NWAC shrink by 7.5% (the midpoint) in '06, our domestic industry ASM forecast goes from +2% y/y to flat, which could potentially be favorable for airline pricing (yields). *** NWAC AND DAL INTIMATE CAPACITY RESTRAINT. After their filing yesterday, NWAC's CEO indicated 4Q:05 capacity could decline 5-6% y/y, while Delta announced plans to accelerate its fleet simplification plan, removing four aircraft types by the end of 2006. *** BIGGEST BENEFICIARIES LIKELY TO BE LOW COST CARRIERS. NWAC and DAL account for roughly 26% of domestic capacity, which, if trimmed by 7.5% equates to a 2% pt reduction in industry capacity. We believe LCC-heavy routes are likely to see a disproportionate benefit from potential reductions at DAL and NWAC, with AAI, AWA, and JBLU in particular having an easier path for growth. -

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ORDER TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2E FEDERAL AVIATION Effective Date: ADMINISTRATION July 24, 2014 Air Traffic Organization Policy Subject: Contractions Includes Change 1 dated 11/13/14 https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/CNT/3-3.HTM A 3- Company Country Telephony Ltr AAA AVICON AVIATION CONSULTANTS & AGENTS PAKISTAN AAB ABELAG AVIATION BELGIUM ABG AAC ARMY AIR CORPS UNITED KINGDOM ARMYAIR AAD MANN AIR LTD (T/A AMBASSADOR) UNITED KINGDOM AMBASSADOR AAE EXPRESS AIR, INC. (PHOENIX, AZ) UNITED STATES ARIZONA AAF AIGLE AZUR FRANCE AIGLE AZUR AAG ATLANTIC FLIGHT TRAINING LTD. UNITED KINGDOM ATLANTIC AAH AEKO KULA, INC D/B/A ALOHA AIR CARGO (HONOLULU, UNITED STATES ALOHA HI) AAI AIR AURORA, INC. (SUGAR GROVE, IL) UNITED STATES BOREALIS AAJ ALFA AIRLINES CO., LTD SUDAN ALFA SUDAN AAK ALASKA ISLAND AIR, INC. (ANCHORAGE, AK) UNITED STATES ALASKA ISLAND AAL AMERICAN AIRLINES INC. UNITED STATES AMERICAN AAM AIM AIR REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA AIM AIR AAN AMSTERDAM AIRLINES B.V. NETHERLANDS AMSTEL AAO ADMINISTRACION AERONAUTICA INTERNACIONAL, S.A. MEXICO AEROINTER DE C.V. AAP ARABASCO AIR SERVICES SAUDI ARABIA ARABASCO AAQ ASIA ATLANTIC AIRLINES CO., LTD THAILAND ASIA ATLANTIC AAR ASIANA AIRLINES REPUBLIC OF KOREA ASIANA AAS ASKARI AVIATION (PVT) LTD PAKISTAN AL-AAS AAT AIR CENTRAL ASIA KYRGYZSTAN AAU AEROPA S.R.L. ITALY AAV ASTRO AIR INTERNATIONAL, INC. PHILIPPINES ASTRO-PHIL AAW AFRICAN AIRLINES CORPORATION LIBYA AFRIQIYAH AAX ADVANCE AVIATION CO., LTD THAILAND ADVANCE AVIATION AAY ALLEGIANT AIR, INC. (FRESNO, CA) UNITED STATES ALLEGIANT AAZ AEOLUS AIR LIMITED GAMBIA AEOLUS ABA AERO-BETA GMBH & CO., STUTTGART GERMANY AEROBETA ABB AFRICAN BUSINESS AND TRANSPORTATIONS DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF AFRICAN BUSINESS THE CONGO ABC ABC WORLD AIRWAYS GUIDE ABD AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC ICELAND ATLANTA ABE ABAN AIR IRAN (ISLAMIC REPUBLIC ABAN OF) ABF SCANWINGS OY, FINLAND FINLAND SKYWINGS ABG ABAKAN-AVIA RUSSIAN FEDERATION ABAKAN-AVIA ABH HOKURIKU-KOUKUU CO., LTD JAPAN ABI ALBA-AIR AVIACION, S.L. -

Hull Loss Accidents

Hull Loss Accidents Western Built Commercial Jets (>60,000 lbs) 1960 thru 2005 10 . 0 0 8.00 5.64 6.00 es per million departures 4.00 2.16 1.47 2.00 1.29 0.89 Hull Loss Rate in loss 0.00 60's 70's 80's 90's 2000's Source: Boeing, AvSoft Figure 1 The Fleet - 2006 Type Western Built Eastern Built Total Turbojets 17,609 1,839 19,448 Turboprops 4,774 1,710 6,484 Business Jets 12,724 Figure 2 Major Accidents Business Jets 1 January to 31 December 2006 Date Operator Aircraft Location Phase Fatal 2 January Avcom Hawker 700 Kharkov, Ukraine Approach 3 24 January Goship Air Citation V Carlsbad, CA, USA Landing 4 15 February Jet 2000 Falcon 20 Kiel, Germany Landing 0 16 February Lech Air Citation I Busckin, Iraq Descent 6 2 June International Jet Charter Lear 35 Groton, CT, USA Approach 2 26 June Great Ideas Corp Hawker F3 Barcelona, Venezuela Landing 0 5 July Vigojet Sabreliner Mexico City, Mexico Landing 0 19 July Tomco II Citation Encore Cresco, IA, USA Landing 2 28 August Netjets Hawker 800 Carson City, NV, USA Descent 0 30 December Fact Air Sabreliner Culiacan, Mexico Approach 2 Source: Ascend Figure 3 Major Accidents Commercial Turboprops (> 14 seats) 1 January to 31 December 2006 Date Operator Aircraft Location Phase Fatal 2 January Ruenzori Airways Antonov 26 Fataki, DR Congo Climb 0 24 January Aerolift Antonov 12 Mbuji Mayi, DR Congo Landing 0 5 February Air Cargo Carriers Shorts 360 Watertown, WI, USA Enroute 3 8 February Tri Coastal Airlines Metro II Paris, TN, USA Enroute 1 11 March Air Deccan ATR 72 Bangalore, India Landing 0 18 March -

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE on AIR LAW (Montréal, 20 April to 2

DCCD Doc No. 28 28/4/09 (English only) INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON AIR LAW (Montréal, 20 April to 2 May 2009) CONVENTION ON COMPENSATION FOR DAMAGE CAUSED BY AIRCRAFT TO THIRD PARTIES AND CONVENTION ON COMPENSATION FOR DAMAGE TO THIRD PARTIES, RESULTING FROM ACTS OF UNLAWFUL INTERFERENCE INVOLVING AIRCRAFT (Presented by the Air Crash Victims Families Group) 1. INTRODUCTION – SUPPLEMENTAL AND OTHER COMPENSATIONS 1.1 The apocalyptic terrorist attack by the means of four hi-jacked planes committed against the World Trade Center in New York, NY , the Pentagon in Arlington, VA and the aborted flight ending in a crash in the rural area in Shankville, PA ON September 11th, 2001 is the only real time example that triggered this proposed Convention on Compensation for Damage to Third Parties from Acts of Unlawful Interference Involving Aircraft. 1.2 It is therefore important to look towards the post incident resolution of this tragedy in order to adequately and pro actively complete ONE new General Risk Convention (including compensation for ALL catastrophic damages) for the twenty first century. 2. DISCUSSION 2.1 Immediately after September 11th, 2001 – the Government and Congress met with all affected and interested parties resulting in the “Air Transportation Safety and System Stabilization Act” (Public Law 107-42-Sept. 22,2001). 2.2 This Law provided the basis for Rules and Regulations for: a) Airline Stabilization; b) Aviation Insurance; c) Tax Provisions; d) Victims Compensation; and e) Air Transportation Safety. DCCD Doc No. 28 - 2 - 2.3 The Airline Stabilization Act created the legislative vehicle needed to reimburse the air transport industry for their losses of income as a result of the flight interruption due to the 911 attack.