2020 Mythological Studies Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tolkien As a Child of <I>The Green Fairy Book</I>

Volume 26 Number 1 Article 9 10-15-2007 Tolkien as a Child of The Green Fairy Book Ruth Berman Independent Scholar Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Berman, Ruth (2007) "Tolkien as a Child of The Green Fairy Book," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 26 : No. 1 , Article 9. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol26/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Considers the influence of some of olkienT ’s earliest childhood reading, the Andrew Lang fairy books, and the opinions he expressed about these books in “On Fairy-stories.” Examines the series for possible influences on olkienT ’s fiction in its portrayal of fairy queens, dragons, and other fantasy tropes. -

Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister

Reading Guide Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister By Gregory Maguire ISBN: 9780060987527 Summary We have all heard the story of Cinderella, the beautiful child cast out to slave among the ashes. But what of her stepsisters, the homely pair exiled into ignominy by the fame of their lovely sibling? What fate befell those untouched by beauty...and what curses accompanied Cinderella's exquisite looks? Set against the rich backdrop of seventeenth-century Holland, Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister tells the story of Iris, an unlikely heroine who finds herself swept from the lowly streets of Haarlem to a strange world of wealth, artifice, and ambition. Iris's path quickly becomes intertwined with that of Clara, the mysterious and unnaturally beautiful girl destined to become her sister. Far more than a mere fairy-tale, Confessions is a novel of beauty and betrayal, illusion and understanding, reminding us that deception can be unearthed -- and love unveiled -- in the most unexpected of places. Questions for Discussion 1. While versions of the Cinderella story go back at least a thousand years, most Americans are familiar with the tale of the glass slippers, the pumpkin coach, and the fairy godmother. In what ways does Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister contain the magical echo of this tale, and in what ways does it embrace the traditions of a straight historical novel? 2. Confessions is, in part, about the difficulty and the value of seeing-seeing paintings, seeing beauty, seeing the truth. Each character in Confessions has blinkers or blinders on about one thing or another. What do the characters overlook, in themselves and in one another? 3. -

A Philosophical Inquiry Into the Development of the Notion of Kalos Kagathos from Homer to Aristotle

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2006 A philosophical inquiry into the development of the notion of kalos kagathos from Homer to Aristotle Geoffrey Coad University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Philosophy Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Coad, G. (2006). A philosophical inquiry into the development of the notion of kalos kagathos from Homer to Aristotle (Master of Philosophy (MPhil)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/13 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PHILOSOPHICAL INQUIRY INTO THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE NOTION OF KALOS KAGATHOS FROM HOMER TO ARISTOTLE Dissertation submitted for the Degree of Master of Philosophy Geoffrey John Coad School of Philosophy and Theology University of Notre Dame, Australia December 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract iv Declaration v Acknowledgements vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: The Fish Hook and Some Other Examples 6 The Sun – The Source of Beauty 7 Some Instances of Lack of Beauty: Adolf Hitler and Sharp Practices in Court 9 The Kitchen Knife and the Samurai Sword 10 CHAPTER 2: Homer 17 An Historical Analysis of the Phrase Kalos Kagathos 17 Herman Wankel 17 Felix Bourriott 18 Walter Donlan 19 An Analysis of the Terms Agathos, Arete and Other Related Terms of Value in Homer 19 Homer’s Purpose in Writing the Iliad 22 Alasdair MacIntyre 23 E. -

Abstract Rereading Female Bodies in Little Snow-White

ABSTRACT REREADING FEMALE BODIES IN LITTLE SNOW-WHITE: INDEPENDENCE AND AUTONOMY VERSUS SUBJUGATION AND INVISIBILITY By Dianne Graf In this thesis, the circumstances and events that motivate the Queen to murder Snow-White are reexamined. Instead of confirming the Queen as wicked, she becomes the protagonist. The Queen’s actions reveal her intent to protect her physical autonomy in a patriarchal controlled society, as well as attempting to prevent patriarchy from using Snow-White as their reproductive property. REREADING FEMALE BODIES IN LITTLE SNOW-WHITE: INDEPENDENCE AND AUTONOMY VERSUS SUBJUGATION AND INVISffiILITY by Dianne Graf A Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts-English at The University of Wisconsin Oshkosh Oshkosh WI 54901-8621 December 2008 INTERIM PROVOST AND VICE CHANCELLOR t:::;:;:::.'-H.~"""-"k.. Ad visor t 1.. - )' - i Date Approved Date Approved CCLs~ Member FORMAT APPROVAL 1~-05~ Date Approved ~~ I • ~&1L Member Date Approved _ ......1 .1::>.2,-·_5,",--' ...L.O.LJ?~__ Date Approved To Amanda Dianne Graf, my daughter. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you Dr. Loren PQ Baybrook, Dr. Karl Boehler, Dr. Christine Roth, Dr. Alan Lareau, and Amelia Winslow Crane for your interest and support in my quest to explore and challenge the fairy tale world. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………… 1 CHAPTER I – BRIEF OVERVIEW OF THE LITERARY FAIRY TALE AND THE TRADITIONAL ANALYSIS OF THE FEMALE CHARACTERS………………..………………………. 3 CHAPTER II – THE QUEEN STEP/MOTHER………………………………….. 19 CHAPTER III – THE OLD PEDDLER WOMAN…………..…………………… 34 CHAPTER IV – SNOW-WHITE…………………………………………….…… 41 CHAPTER V – THE QUEEN’S LAST DANCE…………………………....….... 60 CHAPTER VI – CONCLUSION……………………………………………..…… 67 WORKS CONSULTED………..…………………………….………………..…… 70 iv 1 INTRODUCTION In this thesis, the design, framing, and behaviors of female bodies in Little Snow- White, as recorded by Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm will be analyzed. -

Eris and Epos Composition, Competition, and the Domestication of Strife

Eris and Epos Composition, Competition, and the Domestication of Strife Joel P. Christensen Brandeis University [email protected] Abstract This article examines the development of the theme of eris in Hesiod and Homer. Start- ing from the relationship between the destructive strife in the Theogony (225) and the two versions invoked in the Works and Days (11–12), I argue that considering the two forms of strife as echoing zero and positive sum games helps us to identify the cultural and compositional force of eris as cooperative competition. After establishing eris as a compositional theme from the perspective of oral poetics, I then argue that it develops from the perspective of cosmic history, that is, from the creation of the universe in Hes- iod’s Theogony through the Homeric epics and into its double definition in the Works and Days.To explore and emphasize how this complementarity is itself a manifestation of eris, I survey its deployment in our major extant epic poems. Keywords eris – competition – conflict – poetics – rivalry In Cypria fr. 1, Zeus fans “the flames of the great strife of the Trojan war / to lighten the [earth’s] burden with death” (ῥιπίσσας πολέμου μεγάλην ἔριν Ἰλιακοῖο, 5).* Similarly, in Hesiod (fr. 204 M-W), when strife divides the gods at the birth of Hermione—“all the gods were of two minds / because of the strife” (πάν- τες δὲ θεοὶ δίχα θυμὸν ἔθεντο / ἐξ ἔριδος, 94–95)—Zeus hastens the destruction of the Heroes: “And then he hastened to extinguish the great race of human * A version of this article was given at the Heartland Graduate Conference in Ancient Stud- ies at the University of Missouri in 2015. -

“100% Sanctification – Guaranteed” – Part 2 100% Sanctification

THE SECOND EPISTLE OF PETER TO THE CHURCH OF THE DISPERSION THROUGHOUT THE WORLD 2 PETER CHAPTER 1:5-9 MEDIA REFERENCE NUMBER SMX995 OCTOBER 27, 2019 THE TITLE OF THE MESSAGE: “100% Sanctification – Guaranteed” – Part 2 SUBJECT TOPICALLY REFERENCED UNDER: Faithfulness, Finishing, Church, Christianity, Discipleship 2 Peter 1:5-9 But also for this very reason, giving all diligence, add to your faith virtue, to virtue knowledge, 6 to knowledge self-control, to self-control perseverance, to perseverance godliness, 7 to godliness brotherly kindness, and to brotherly kindness love. 8 For if these things are yours and abound, you will be neither barren nor unfruitful in the knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ. 9 For he who lacks these things is shortsighted, even to blindness, and has forgotten that he was cleansed from his old sins. 100% Sanctification – Guaranteed! We have read throughout the Old Testament that God called His people to be set apart from this world and to be set apart for Him That Old Testament Requirement is Fulfilled in the New Testament Relationship And in Peter’s Day - The Early Church was Increasingly Thankful for that. It’s success / It’s effect / It’s influence / It’s earthly calling / From its heavenly position. 1 Thessalonians 5:23-24 Now may the God of peace Himself sanctify you completely; and may your whole spirit, soul, and body be preserved blameless at the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ. 24 He who calls you is faithful, who also will do it. Reviewing Part 1 of Our Previous Teaching 100% Sanctification – Guaranteed! 1.) Means that we co-operate with God vs. -

Cinderella – Beautiful Girl

Cinderella – Beautiful Girl Once upon a time, there was a beautiful girl named Cinderella. She lived with her wicked stepmother and two stepsisters. They treated Cinderella very badly. One day, they were invited for a grand ball in the king’s palace. But Cinderella’s stepmother would not let her go. Cinderella was made to sew new party gowns for her stepmother and stepsisters, and curl their hair. They then went to the ball, leaving Cinderella alone at home. Cinderella felt very sad and began to cry. Suddenly, a fairy godmother appeared and said, “Don’t cry, Cinderella! I will send you to the ball!” But Cinderella was sad. She said, “I don’t have a gown to wear for the ball!” The fairy godmother waved her magic wand and changed Cinderella’s old clothes into a beautiful new gown! The fairy godmother then touched Cinderella’s feet with the magic wand. And lo! She had beautiful glass slippers! “How will I go to the grand ball?” asked Cinderella. The fairy godmother found six mice playing near a pumpkin, in the kitchen. She touched them with her magic wand and the mice became four shiny black horses and two coachmen and the pumpkin turned into a golden coach. Cinderella was overjoyed and set off for the ball in the coach drawn by the six black horses. Before leaving. the fairy godmother said, “Cinderella, this magic will only last until midnight! You must reach home by then!” When Cinderella entered the palace, everybody was struck by her beauty. Nobody, not even Cinderella’s stepmother or stepsisters, knew who she really was in her pretty clothes and shoes. -

Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films Through Grotesque Aesthetics

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 9-10-2015 12:00 AM Who's the Fairest of Them All? Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films through Grotesque Aesthetics Leah Persaud The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Angela Borchert The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Leah Persaud 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Persaud, Leah, "Who's the Fairest of Them All? Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films through Grotesque Aesthetics" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3244. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3244 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHO’S THE FAIREST OF THEM ALL? DEFINING AND SUBVERTING THE FEMALE BEAUTY IDEAL IN FAIRY TALE NARRATIVES AND FILMS THROUGH GROTESQUE AESTHETICS (Thesis format: Monograph) by Leah Persaud Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Leah Persaud 2015 Abstract This thesis seeks to explore the ways in which women and beauty are depicted in the fairy tales of Giambattista Basile, the Grimm Brothers, and 21st century fairy tale films. -

Knowledge 3 Teacher Guide Grade 1 Different Lands, Similar Stories Grade 1 Knowledge 3 Different Lands, Similar Stories

¬CKLA FLORIDA Knowledge 3 Teacher Guide Grade 1 Different Lands, Similar Stories Grade 1 Knowledge 3 Different Lands, Similar Stories Teacher Guide ISBN 978-1-68391-612-3 © 2015 The Core Knowledge Foundation and its licensors www.coreknowledge.org © 2021 Amplify Education, Inc. and its licensors www.amplify.com All Rights Reserved. Core Knowledge Language Arts and CKLA are trademarks of the Core Knowledge Foundation. Trademarks and trade names are shown in this book strictly for illustrative and educational purposes and are the property of their respective owners. References herein should not be regarded as affecting the validity of said trademarks and trade names. Printed in the USA 01 BR 2020 Grade 1 | Knowledge 3 Contents DIFFERENT LANDS, SIMILAR STORIES Introduction 1 Lesson 1 Cinderella 6 Introducing the Read-Aloud (10 min) Read-Aloud (30 min) Application (20 min) • Core Connections/Domain • Purpose for Listening • Vocabulary Instructional Activity: Introduction Instructions • “Cinderella” • Where Are We? • Somebody Wanted But So Then • Comprehension Questions • Word Work: Worthy Lesson 2 The Girl with the Red Slippers 22 Introducing the Read-Aloud (10 min) Read-Aloud (30 min) Application (20 min) • What Have We Already Learned? • Purpose for Listening • Drawing the Read-Aloud • Where Are We? • “The Girl with the Red Slippers” • Comprehension Questions • Word Work: Cautiously Lesson 3 Billy Beg 36 Introducing the Read-Aloud (10 min) Read-Aloud (30 min) Application (20 min) • What Have We Already Learned? • Purpose for Listening • -

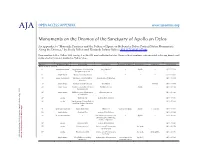

Supplemental Content: Monuments on the Dromos of the Sanctuary Of

AJA OPEN ACCESS: APPENDIX www.ajaonline.org Monuments on the Dromos of the Sanctuary of Apollo on Delos An appendix to “Honorific Practices and the Politics of Space on Hellenistic Delos: Portrait Statue Monuments Along the Dromos,” by Sheila Dillon and Elizabeth Palmer Baltes (AJA 117 [2013] 207–46). Base numbers follow Vallois 1923 (see fig. 3 in the AJA print-published article). Bases without numbers were recorded as having been found in the area but were not marked on Vallois’ plan. Base No. Monument Type Honorand(s) Dedicator(s) Reason(s) for Honor Dedicated to Sculptor(s) Reference(s) Bases set up ca. 250–200 5 equestrian statue Epigenes, son of Andron, the King Attalos I – Apollo – IG 11 4 1109 Pergamene general 8 single statue Donax, son of Apollonios – – – – IG 11 4 1202 16 group monument Aischylo(. .) and his father, Mennis, son of Nikarchos – – – IG 11 4 1168 Nikarchos 19 single statue female, Hellenistic queen? the Delians – – Thoinias IG 11 4 1088 20 single statue Autokles, son of Ainesidemos, Autokles, his son – Apollo – IG 11 4 1194 from Chalcidia 117.2) 25 single statue Phildemos, son of Pythermos Eumedes, his son – – – IG 11 4 1193 of Chalcedon 27 exedra family group demos of the Delians – – – IG 11 4 1090 33 exedra family group of Jason, Eukleia, – – – – IG 11 4 1203 Timokleia, Straton, Timokleia, Sillis 41 victory monument Gallic dedication Attalos I(?) victory over Gauls Apollo (. .)epoiei IG 11 4 1110 50c single statue Aichmokritos demos of the Delians – – – IG 11 4 1094 American Journal of Archaeology American 53 -

Issun Boshi: One-Inch

IIssunssun BBoshi:oshi: OOne-Inchne-Inch BBoyoy 6 Lesson Objectives Core Content Objectives Students will: Explain that f ctional stories come from the author’s imagination Identify folktales as a type of f ction Explain that stories have a beginning, middle, and end Describe the characters, plot, and setting of “Issun Boshi: One- Inch Boy” Explain that people from different lands tell similar stories Language Arts Objectives The following language arts objectives are addressed in this lesson. Objectives aligning with the Common Core State Standards are noted with the corresponding standard in parentheses. Refer to the Alignment Chart for additional standards addressed in all lessons in this domain. Students will: Demonstrate understanding of the central message or lesson in “Issun Boshi: One-Inch Boy” (RL.1.2) Recount and identify the lesson in folktales from diverse cultures, such as “Issun Boshi: One-Inch Boy” (RL.1.2) Orally compare and contrast similar stories from different cultures, such as “Tom Thumb,” “Thumbelina,” and “Issun Boshi: One-Inch Boy” (RL.1.9) Draw and describe one of the scenes from “Issun Boshi: One- Inch Boy” (W.1.2) Describe characters, settings, and events as depicted in drawings of one of the scenes from “Issun Boshi: One-Inch Boy” (SL.1.4) Different Lands, Similar Stories 6 | Issun Boshi: One-Inch Boy 79 © 2013 Core Knowledge Foundation Add suff cient detail to a drawing of a scene from “Issun Boshi: One-Inch Boy” (SL.1.5) Prior to listening to “Issun Boshi: One-Inch Boy,” identify orally what they know and have learned about folktales, “Tom Thumb” and “Thumbelina” Core Vocabulary astonished, adj. -

CTG Resume Theatre Only No TV

Clear Talent Group 264 West 40th St. #203 New York, NY 10018 212 840-4100 (o) 212 967-4567 (f) Marjorie Failoni AEA Broadway Escape to Margaritaville. Swing/u/s Tammy/Dance Captain Marquis Theatre (La Jolla and Tour cast as well) Dir: Christopher Ashley Chor: Kelly Devine National Tours 9 to 5 Assoc Chor/Swing/Dance Captain 1st National Tour Dir: Jeff Calhoun Chor: Lisa Stevens High School Musical Swing/u/s Mrs. Wilson/Dance Captain 1st Natl., Disney Theatricals Dir: Jeff Calhoun Chop: Lisa Stevens Theatre Oklahoma! Ellen/u/s Laurey/Dance Captain North Shore Music Theatre Dir: Charles Repole Chor: Mara Newbery Greer Elf Waitress/Ensemble Ogunquit Playhouse Dir/Chor: Connor Gallagher A Christmas Story Swing/Dance Captain Paper Mill Playhouse Dir: Brandon Ivie Chor: Mara Newbery Greer Kris Kringle: the Musical Dance Captain/Ensemble Proctors Theatre Dir: Frank Galgano How to Succeed In Business…. Miss Krumholtz/Dance Captain Flat Rock Playhouse Dir/Chor: Richard J Hinds The Witches of Eastwick Marge/Dance Capt/Flight Capt Ogunquit Playhouse Dir: Shaun Kerrison Chor: Lisa Stevens The Little Mermaid Allana/Ensemble TUTS/Dallas/La Mirada Dir: Glenn Casale Chor: John MacInnis 42nd Street Phyllis Dale Maine State Music Theatre Dir: Charles Repole Chor: Michael Lichtefeld Shrek Fairy Godmother/Fiona Double The MUNY Dir: John Tartaglia Hairspray LouAnn The Cape Playhouse Dir: Mark Martino Chor: Dennis Jones Special Events Target Fashion Week. Performer Armory NY Chor: Sarah O’Gleby Samsung Unpacked 2013 Performer Radio City Music Hall Dir: Jeff Calhoun Spring Gala 2010 Performer The Kennedy Center Chor: Josh Prince Training BFA in Musical Theatre – The University of Michigan Special Skills 2 point harness flying (Fly by Foy), Tap, Pointe, Pas de Deux/Partnering, Jazz, Hip-Hop, Basic Skateboarding, Piano, Basic French.