Socio-Cultural Determinants Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wahu Kaara of Kenya

THE STRENGTH OF MOTHERS: The Life and Work of Wahu Kaara of Kenya By Alison Morse, Peace Writer Edited by Kaitlin Barker Davis 2011 Women PeaceMakers Program Made possible by the Fred J. Hansen Foundation *This material is copyrighted by the Joan B. Kroc Institute for Peace & Justice. For permission to cite, contact [email protected], with “Women PeaceMakers – Narrative Permissions” in the subject line. THE STRENGTH OF MOTHERS WAHU – KENYA TABLE OF CONTENTS I. A Note to the Reader ……………………………………………………….. 3 II. About the Women PeaceMakers Program ………………………………… 3 III. Biography of a Woman PeaceMaker – Wahu Kaara ….…………………… 4 IV. Conflict History – Kenya …………………………………………………… 5 V. Map – Kenya …………………………………………………………………. 10 VI. Integrated Timeline – Political Developments and Personal History ……….. 11 VII. Narrative Stories of the Life and Work of Wahu Kaara a. The Path………………………………………………………………….. 18 b. Squatters …………………………………………………………………. 20 c. The Dignity of the Family ………………………………………………... 23 d. Namesake ………………………………………………………………… 25 e. Political Awakening……………………………………………..………… 27 f. Exile ……………………………………………………………………… 32 g. The Transfer ……………………………………………………………… 39 h. Freedom Corner ………………………………………………………….. 49 i. Reaffirmation …………………….………………………………………. 56 j. A New Network………………….………………………………………. 61 k. The People, Leading ……………….…………………………………….. 68 VIII. A Conversation with Wahu Kaara ….……………………………………… 74 IX. Best Practices in Peacebuilding …………………………………………... 81 X. Further Reading – Kenya ………………………………………………….. 87 XI. Biography of a Peace Writer -

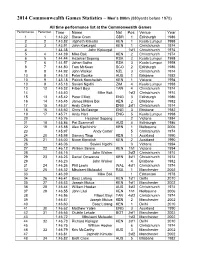

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics – Men's 800M

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics – Men’s 800m (880yards before 1970) All time performance list at the Commonwealth Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 1:43.22 Steve Cram GBR 1 Edinburgh 1986 2 2 1:43.82 Japheth Kimutai KEN 1 Kuala Lumpur 1998 3 3 1:43.91 John Kipkurgat KEN 1 Christchurch 1974 4 1:44.38 John Kipkurgat 1sf1 Christchurch 1974 5 4 1:44.39 Mike Boit KEN 2 Christchurch 1974 6 5 1:44.44 Hezekiel Sepeng RSA 2 Kuala Lumpur 1998 7 6 1:44.57 Johan Botha RSA 3 Kuala Lumpur 1998 8 7 1:44.80 Tom McKean SCO 2 Edinburgh 1986 9 8 1:44.92 John Walker NZL 3 Christchurch 1974 10 9 1:45.18 Peter Bourke AUS 1 Brisbane 1982 10 9 1:45.18 Patrick Konchellah KEN 1 Victoria 1994 10 9 1:45.18 Savieri Ngidhi ZIM 4 Kuala Lumpur 1998 13 12 1:45.32 Filbert Bayi TAN 4 Christchurch 1974 14 1:45.40 Mike Boit 1sf2 Christchurch 1974 15 13 1:45.42 Peter Elliott ENG 3 Edinburgh 1986 16 14 1:45.45 James Maina Boi KEN 2 Brisbane 1982 17 15 1:45.57 Andy Carter ENG 2sf1 Christchurch 1974 18 16 1:45.60 Chris McGeorge ENG 3 Brisbane 1982 19 17 1:45.71 Andy Hart ENG 5 Kuala Lumpur 1998 20 1:45.76 Hezekiel Sepeng 2 Victoria 1994 21 18 1:45.86 Pat Scammell AUS 4 Edinburgh 1986 22 19 1:45.88 Alex Kipchirchir KEN 1 Melbourne 2006 23 1:45.97 Andy Carter 5 Christchurch 1974 24 20 1:45.98 Sammy Tirop KEN 1 Auckland 1990 25 21 1:46.00 Nixon Kiprotich KEN 2 Auckland 1990 26 1:46.06 Savieri Ngidhi 3 Victoria 1994 27 22 1:46.12 William Serem KEN 1h1 Victoria 1994 28 1:46.15 John Walker 2sf2 Christchurch 1974 29 23 1:46.23 Daniel Omwanza KEN 3sf1 Christchurch -

English Version

Diaspora Voting and Ethnic Politics in Kenya Beth Elise Whitaker and Salma Inyanji To cite this article: Beth Elise Whitaker, Salma Inyanji, “Vote de la diaspora et ethnicité au Kenya,” Afrique contemporaine 4/2015 (n° 256), p. 73-89. URL : www.cairn.info/revue-afrique-contemporaine-2015-4-page-73.htm. ABSTRACT: Many African governments have extended voting rights to nationals living abroad, but little is known about the political behavior of diaspora populations. In the context of Kenya, where the 2010 constitution authorized diaspora voting, we ask whether nationals living abroad are as likely to vote along ethnic lines as their counterparts at home. Using data from public opinion polls prior to the March 2013 presidential election, we compare levels of support for presumed ethnic candidates among Kenyans surveyed in the diaspora and those surveyed in the country. Overall, diaspora respondents were significantly less likely than in-country respondents to support the presumed ethnic candidate from their home province. The results provide preliminary support for our hypothesis that diaspora Africans are less likely to vote along ethnic lines than their in-country counterparts, and thus are less reliable for the construction of ethnic coalitions. More survey data are needed from Kenyans and other Africans living abroad to further examine the relationship between diaspora voting and ethnicity in African politics. As migration patterns have become increasingly global, African diaspora populations have emerged as an important political consideration (Akyeampong 2000). The African Union has held a series of conferences to engage the diaspora with a view toward recognizing it as the continent’s “sixth region.” African governments have been reaching out to nationals living abroad to seek their economic and political participation at home. -

List of All Olympics Winners in Kenya

Location Year Player Sport Medals Event Results London 2012 Sally Jepkosgei KIPYEGO Athletics Silver 10000m 30:26.4 London 2012 Vivian CHERUIYOT Athletics Bronze 10000m 30:30.4 London 2012 Abel Kiprop MUTAI Athletics Bronze 3000m steeplechase 08:19.7 London 2012 Ezekiel KEMBOI Athletics Gold 3000m steeplechase 08:18.6 London 2012 Vivian CHERUIYOT Athletics Silver 5000m 15:04.7 London 2012 Thomas Pkemei LONGOSIWA Athletics Bronze 5000m 13:42.4 London 2012 David Lekuta RUDISHA Athletics Gold 800m 1:40.91 London 2012 Timothy KITUM Athletics Bronze 800m 1:42.53 London 2012 Priscah JEPTOO Athletics Silver marathon 02:23:12 London 2012 Wilson Kipsang KIPROTICH Athletics Bronze marathon 02:09:37 London 2012 Abel KIRUI Athletics Silver marathon 02:08:27 Beijing 2008 Micah KOGO Athletics Bronze 10000m 27:04.11 Beijing 2008 Nancy Jebet LAGAT Athletics Gold 1500m 04:00.2 Beijing 2008 Asbel Kipruto KIPROP Athletics Gold 1500m 03:33.1 Beijing 2008 Eunice JEPKORIR Athletics Silver 3000m steeplechase 9:07.41 Beijing 2008 Brimin Kiprop KIPRUTO Athletics Gold 3000m steeplechase 08:10.3 Beijing 2008 Richard Kipkemboi MATEELONG Athletics Bronze 3000m steeplechase 08:11.0 Beijing 2008 Edwin Cheruiyot SOI Athletics Bronze 5000m 13:06.22 Beijing 2008 Eliud Kipchoge ROTICH Athletics Silver 5000m 13:02.80 Beijing 2008 Janeth Jepkosgei BUSIENEI Athletics Silver 800m 01:56.1 Beijing 2008 Wilfred BUNGEI Athletics Gold 800m 01:44.7 Beijing 2008 Pamela JELIMO Athletics Gold 800m 01:54.9 Beijing 2008 Alfred Kirwa YEGO Athletics Bronze 800m 01:44.8 Beijing 2008 Samuel -

Mygov Issue 5 AUGUST 04, 2020

FOR FREE CIRCULATION www.mygov.go.ke August 4, 2020 The best prevention YOUR WEEKLY REVIEW against the coronavirus is still washing your hands and keeping safe social distance For FINAL Issue No. 5/2020-2021 +254 020 4920000 [email protected] Kenya to remove roadblocks The Week In numbers along the Northern Corridor NEC Main line Sh1.7b SOUTH SUDAN The cost of a floating NEC Branch line PS says inland Juba pedestrian bridge to be constructed at container the Liwatoni area of depots to be Mombasa Island. upgraded as well as KENYA 3,000 Tororo UGANDA Number of teachers constructing from private and Kampala educational facilities Kisumu refurbishing Nairobi in Nakuru in need of Kigali food of port and oil RWANDA pipelines to TANZANIA Bujumbura 552,000 promote trade BURUNDI Mombasa Kenyans living with Diabetes according BY BERNADETTE KHADULI/ to International HILARY MONGERA said Dr. Mwakima. Transport Coordination Au- Diabetes Federation thority Executive Commit- (IDF) data enya is set to remove tee was speaking during the all roadblocks along opening of the virtual meet- Kthe Northern Cor- ing. Kampala –Uganda. But since She said the involvement 612 ridor, as well as expand and In a press statement to the outbreak of coronavirus of the public sector can be Cases of child upgrade transport infra- newsrooms, Dr. Mwakima pandemic in the region and achieved if the countries for- labour that have structure in order to promote said Kenya also intends to containment measures put mulate policies, regulatory been captured by trade in the East African extend the Standard Gauge in place to curb COVID-19 and institutional frameworks Child Protection Community region. -

Rethinking Mau Mau in Colonial Kenya This Page Intentionally Left Blank Pal-Alam-00Fm.Qxd 6/14/07 6:00 PM Page Iii

pal-alam-00fm.qxd 6/14/07 6:00 PM Page i Rethinking Mau Mau in Colonial Kenya This page intentionally left blank pal-alam-00fm.qxd 6/14/07 6:00 PM Page iii Rethinking Mau Mau in Colonial Kenya S. M. Shamsul Alam, PhD pal-alam-00fm.qxd 6/14/07 6:00 PM Page iv Rethinking Mau Mau in Colonial Kenya Copyright © S. M. Shamsul Alam, PhD, 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quo- tations embodied in critical articles or reviews. First published in 2007 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN™ 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 and Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England RG21 6XS. Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN-13: 978-1-4039-8374-9 ISBN-10: 1-4039-8374-7 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Alam, S. M. Shamsul, 1956– Rethinking Mau Mau in colonial Kenya / S. M. Shamsul Alam. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-4039-8374-7 (alk. paper) 1. Kenya—History—Mau Mau Emergency, 1952–1960. 2. Mau Mau History. I. Title. DT433.577A43 2007 967.62’03—dc22 2006103210 A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library. -

The Kenya General Election

AAFFRRIICCAA NNOOTTEESS Number 14 January 2003 The Kenya General Election: senior ministerial positions from 1963 to 1991; new Minister December 27, 2002 of Education George Saitoti and Foreign Minister Kalonzo Musyoka are also experienced hands; and the new David Throup administration includes several able technocrats who have held “shadow ministerial positions.” The new government will be The Kenya African National Union (KANU), which has ruled more self-confident and less suspicious of the United States Kenya since independence in December 1963, suffered a than was the Moi regime. Several members know the United disastrous defeat in the country’s general election on December States well, and most of them recognize the crucial role that it 27, 2002, winning less than one-third of the seats in the new has played in sustaining both opposition political parties and National Assembly. The National Alliance Rainbow Coalition Kenyan civil society over the last decade. (NARC), which brought together the former ethnically based opposition parties with dissidents from KANU only in The new Kibaki government will be as reliable an ally of the October, emerged with a secure overall majority, winning no United States in the war against terrorism as President Moi’s, fewer than 126 seats, while the former ruling party won only and a more active and constructive partner in NEPAD and 63. Mwai Kibaki, leader of the Democratic Party (DP) and of bilateral economic discussions. It will continue the former the NARC opposition coalition, was sworn in as Kenya’s third government’s valuable mediating role in the Sudanese peace president on December 30. -

All Time Men's World Ranking Leader

All Time Men’s World Ranking Leader EVER WONDER WHO the overall best performers have been in our authoritative World Rankings for men, which began with the 1947 season? Stats Editor Jim Rorick has pulled together all kinds of numbers for you, scoring the annual Top 10s on a 10-9-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1 basis. First, in a by-event compilation, you’ll find the leaders in the categories of Most Points, Most Rankings, Most No. 1s and The Top U.S. Scorers (in the World Rankings, not the U.S. Rankings). Following that are the stats on an all-events basis. All the data is as of the end of the 2019 season, including a significant number of recastings based on the many retests that were carried out on old samples and resulted in doping positives. (as of April 13, 2020) Event-By-Event Tabulations 100 METERS Most Points 1. Carl Lewis 123; 2. Asafa Powell 98; 3. Linford Christie 93; 4. Justin Gatlin 90; 5. Usain Bolt 85; 6. Maurice Greene 69; 7. Dennis Mitchell 65; 8. Frank Fredericks 61; 9. Calvin Smith 58; 10. Valeriy Borzov 57. Most Rankings 1. Lewis 16; 2. Powell 13; 3. Christie 12; 4. tie, Fredericks, Gatlin, Mitchell & Smith 10. Consecutive—Lewis 15. Most No. 1s 1. Lewis 6; 2. tie, Bolt & Greene 5; 4. Gatlin 4; 5. tie, Bob Hayes & Bobby Morrow 3. Consecutive—Greene & Lewis 5. 200 METERS Most Points 1. Frank Fredericks 105; 2. Usain Bolt 103; 3. Pietro Mennea 87; 4. Michael Johnson 81; 5. -

Table of Contents

A Column By Len Johnson TABLE OF CONTENTS TOM KELLY................................................................................................5 A RELAY BIG SHOW ..................................................................................8 IS THIS THE COMMONWEALTH GAMES FINEST MOMENT? .................11 HALF A GLASS TO FILL ..........................................................................14 TOMMY A MAN FOR ALL SEASONS ........................................................17 NO LIGHTNING BOLT, JUST A WARM SURPRISE ................................. 20 A BEAUTIFUL SET OF NUMBERS ...........................................................23 CLASSIC DISTANCE CONTESTS FOR GLASGOW ...................................26 RISELEY FINALLY GETS HIS RECORD ...................................................29 TRIALS AND VERDICTS ..........................................................................32 KIRANI JAMES FIRST FOR GRENADA ....................................................35 DEEK STILL WEARS AN INDELIBLE STAMP ..........................................38 MICHAEL, ELOISE DO IT THEIR WAY .................................................... 40 20 SECONDS OF BOLT BEATS 20 MINUTES SUNSHINE ........................43 ROWE EQUAL TO DOUBELL, NOT DOUBELL’S EQUAL ..........................46 MOROCCO BOUND ..................................................................................49 ASBEL KIPROP ........................................................................................52 JENNY SIMPSON .....................................................................................55 -

Prof. Mike Boit

Prof. Mike Boit Position: Associate Professor Department/Unit/Section: Department of Recreation Management and Exercise Science Area of Specialization: Education in Curriculum Instruction and Physical Education Contact Address: P.O. Box 43844-00100 Nairobi – Kenya Telephone: +254 020 8710901-12 Ext 57284 E-Mail: [email protected] Areas of Interest: Curriculum Development Classroom Supervision Sports Nutrition, Human Anatomy Sports Sociology and Psychology Statistics and Research Methods Physical Education Administration Exercise Physiology Physical Fitness. National and International Appointments 2007 Board of Trustees, Member of Mathare United Sports Association 2005 Director, International Association of Athletics Federations ( IAAF) Athletics Academy at Kenyatta University to serve the Anglophone African Continent. 2003 Chairman of the Stakeholders’ Transitional Committee, a Body Charged with the responsibilities of Streamlining the Running and Management of the Kenyan National Football Federation Between March and June 2004. 2002 Part Time Coach for the Program of Coaching Excellence and Training Seminars for Elite Coaches at the International Sports Training Institute at Life, University, Atlanta, Georgia. 1989-'99 Member of the International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF) Athletes' Commission by the IAAF Council to Represent Anglophone Africa. Member, International Special Olympics Board - Special Olympics International Sports Rules Committee, African Representative. The Committee Reviewed and Published Rules for Special Olympics Summer and Winter Games. Other Appointments 2001Chairman, Department of Exercise and Sport Science, Kenyatta University 1989 Chairman of the Organizing Committee for the First Inter-University Games Held at Kenyatta University 1989 Elected Public Relations Officer for the National Athletic Federation. 1988 Chairman, Department of Physical Education and Games. Honours and Achievements 1996 Honoured by the Special Olympics International for Contributions as Member of the International Rules Committee. -

Mäestikutreening

Mäestikutreening Harry Lemberg Tartu Ülikool Jõulumäe 2013 Siit see algas..... Hapniku hulk õhus Hapniku hulk mere tasapinnal õhus mäestikus 1968 Olympic 1500m Final Ajalugu … Early studies reported improved running performance and increased aerobic capacity at sea-level (SL) after training at altitude Balke, 1964; Balke et. al 1965; & Faulkner et. al 1967 Effects attributed to significant training adaptations that occurred during the experimentation Faulkner et. al 1968 Effects of equivalent sea-level and altitude training on VO2max and running performance Adams WC, Bernauer EM, Dill DB, & Bomar JB, 1975. Aklimatiseerumine Aklimatiseerumine tähendab harjumuspärastest erinevate kliima – ja keskkonnatingimustega kohanemist. Temperatuur Niiskus Ajavahe Kõrgus merepinnast Hapnik! Vastupidavuse tähtsaim mõõt hapniku tarbimisvõime, mis on seotud organismi hingamise – ja vereringeelundite seisundiga. Hapniku tarbimisvõime koosneb kolmest tegurist: Südame löögivõimest (löögisagedus X löögimaht) Kopsumahust Lihaste võimest kasutada hapnikku Hapnik liigub kehas, mis on heas vormis....... Hapniku kaskaad J. Verhošanski 1988 O2 Adsorbtsioon Kopsude ventilatsioon Hematoloogilised Hemodünaamilised O Transport faktorid 2 faktorid HB kont- Tsirkuleeriva Vere Südame Verevoolu sentratsioon vere maht viskoossus minutimaht ümberjaotus O2 Utilisatsioon Mitokondrite Mitokondrite Energeetiliste Müoglobiini tihedus fermentatiivne substraatide sisaldus lihasrakus aktiivsus kontsentratsioon Mäestik ja hapnik Hapnikuvaegus - hapniku osarõhu langus -

1 Birthing Radical Selves

1 Birthing Radical Selves The Making of a Scholar-Activist This chapter chronicles Wangari Muta Maathai’s experiential his- tory with the topics engaged in the rest of the book—environmental management and justice, critical feminisms, democratic spaces, and globalization and global governance systems. It is my hope that the reader will gain a degree of appreciation for the events and journeys that molded Maathai and shaped her politics and critical thinking. Through the seasons of her life, I recount the advent of her activist and scholarly identities, selves, and roles. I draw her narrative primar- ily from her memoir, interviews, and media reports and meld it with Kenyan and global histories of the different seasons of her scholarship and activism. Wangari Muta was born on April 1, 1940, in the village of Ihithe, Nyeri, in the central highlands of what was then British Kenya, to peasant farmers Muta Njugi and Wanjiru Muta, who were members of the Gikuyu ethnic group (Maathai 2007a, 3–4). She was the third of six children and the first daughter of her biological mother. Her earli- est memories on record are mostly connected to experiences with her mother, with whom she was very close. Growing up in a polygamous family, she remembered the four mothers living mostly in harmony and being supportive of each other, although she acknowledged the existence of some dissonance in the family and that her father beat his wives (19). Nevertheless, she reflected on her childhood with un- mistakable nostalgia. Her earliest memories place her family resid- ing and working on a farm in Nakuru belonging to a settler named Mr.