In Kenyan Athletics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

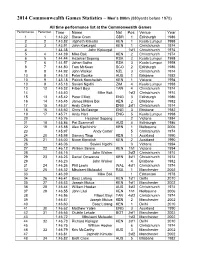

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics–Men's 5000M (3 Mi Before

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics –Men’s 5000m (3 mi before 1970) by K Ken Nakamura All time performance list at the Commonwealth Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 12:56.41 Augustine Choge KEN 1 Melbourne 2006 2 2 12:58.19 Craig Mottram AUS 2 Melbourne 2006 3 3 13:05.30 Benjamin Limo KEN 3 Melbourne 2006 4 4 13:05.89 Joseph Ebuya KEN 4 Melbourne 2006 5 5 13:12.76 Fabian Joseph TAN 5 Melbourne 2006 6 6 13:13.51 Sammy Kipketer KEN 1 Manchester 2002 7 13:13.57 Benjamin Limo 2 Manchester 2002 8 7 13:14.3 Ben Jipcho KEN 1 Christchurch 1974 9 8 13.14.6 Brendan Foster GBR 2 Christchurch 1974 10 9 13:18.02 Willy Kiptoo Kirui KEN 3 Manchester 2002 11 10 13:19.43 John Mayock ENG 4 Manchester 2002 12 11 13:19.45 Sam Haughian ENG 5 Manchester 2002 13 12 13:22.57 Daniel Komen KEN 1 Kuala Lumpur 1998 14 13 13:22.85 Ian Stewart SCO 1 Edinburgh 1970 15 14 13:23.00 Rob Denmark ENG 1 Victoria 1994 16 15 13:23.04 Henry Rono KEN 1 Edmonton 1978 17 16 13:23.20 Phillimon Hanneck ZIM 2 Victoria 1994 18 17 13:23.34 Ian McCafferty SCO 2 Edinburgh 1970 19 18 13:23.52 Dave Black ENG 3 Christchurch 1974 20 19 13:23.54 John Nuttall ENG 3 Victoria 1994 21 20 13:23.96 Jon Brown ENG 4 Victoria 1994 22 21 13:24.03 Damian Chopa TAN 6 Melbourne 2006 23 22 13:24.07 Philip Mosima KEN 5 Victoria 1994 24 23 13:24.11 Steve Ovett ENG 1 Edinburgh 1986 25 24 13:24.86 Andrew Lloyd AUS 1 Auckland 1990 26 25 13:24.94 John Ngugi KEN 2 Auckland 1990 27 26 13:25.06 Moses Kipsiro UGA 7 Melbourne 2006 28 13:25.21 Craig Mottram 6 Manchester 2002 29 27 13:25.63 -

Hansard Report Is for Information Purposes Only

November 24, 2020 NATIONAL ASSEMBLY DEBATES 1 PARLIAMENT OF KENYA THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY THE HANSARD Tuesday, 24th November 2020 The House met at 2.30 p.m. [The Speaker (Hon. Justin Muturi) in the Chair] PRAYERS PETITIONS NON-ALLOCATION OF HEALTH SERVICES CONDITIONAL GRANTS TO UASIN GISHU COUNTY GOVERNMENT Hon. Speaker: Hon. Members, pursuant to Standing Order 225(2)(b), I wish to report to the House that I have received a petition from the leadership of the County Government of Uasin Gishu regarding non-allocation of health services conditional grants to the County Government of Uasin Gishu. Hon. Members, the Petition, which is co-signed by among others the Governor of Uasin Gishu County, H.E. Jackson K. Arap Mandago, and his deputy, holds that the Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital has never received a conditional grant which is provided for under Article 202(2) of the Constitution. The petitioners aver that the elevation of the said hospital from Level 5 to Level 6 is the root cause of this funding stalemate that continues to deny county residents access to emergency, outpatient and inpatient services. Further, Hon. Members, the petitioners assert that the Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital perennially struggles with underfunding, neglect and budget cuts, and is set to miss out on the Kshs4.3 billion earmarked for Level 5 hospitals under the health services conditional grant as contained in the Division of Revenue Act, 2020. Hon. Members, the petitioners are additionally convinced that the criteria used by the Ministry of Health to determine Level 5 hospital status such as availability of facilities and bed capacity is improper since it ignores other critical factors including hospital patients’ attendance rates. -

Landesrekorde Marathon Welt

Landesrekorde Stand: 20.12.2020 Landesrekorde Marathon der Männer Landesrekorde Marathon der Frauen Pl. Land Zeit Diff. Name Jahr Ort Pl. Land Zeit Diff. Name Jahr Ort 1. Kenia 2:01:39 Eliud Kipchoge 2018 Berlin 1. Kenia 2:14:04 Brigid Kosgei 2019 Chicago 2. Äthiopien 2:01:41 (0:00:02) Kenenisa Bekele 2019 Berlin 2. Großbritanien 2:15:25 (0:01:21) Paula Radcliffe 2003 London 3. Türkei 2:04:16 (0:02:37) Kaan Kigen Özbilen 2019 Valencia 3. Äthiopien 2:17:41 (0:03:37) Degefa Workneh 2019 Dubai 4. Bahrain 2:04:43 (0:03:04) El Hassan el-Abbassi 2018 Valencia 4. Israel 2:17:45 (0:03:41) Lonah Chematai Salpeter 2020 Tokio 5. Belgien 2:04:49 (0:03:10) Bashir Abdi 2020 Tokio 5. Japan 2:19:12 (0:05:08) Mizuki Noguchi 2005 Berlin 6. England 2:05:11 (0:03:32) Mo Farah 2018 Chicago 6. Deutschland 2:19:19 (0:05:15) Irina Mikitenko 2008 Berlin 7. Großbritanien 2:05:11 (0:03:32) Mo Farah 2018 Chicago 7. USA 2:19:36 (0:05:32) Deena Kastor 2006 London 8. Uganda 2:05:12 (0:03:33) Felix Chemonges 2019 Toronto 8. China 2:19:39 (0:05:35) Yingjie Sun 2003 Beijing 9. Marokko 2:05:26 (0:03:47) El Mahjoub Dazza 2018 Valencia 9. Namibia 2:19:52 (0:05:48) Helalia Johannes 2020 Valencia 10. Japan 2:05:29 (0:03:50) Suguru Osako 2020 Tokio 10. Rußland 2:20:47 (0:06:43) Galina Bogomolova 2006 Chicago 11. -

The Things Runners Have Built

The Things Runners Have Built Jackie Lebo takes us to Eldoret, Kenya where development is taking place thanks to the investment of earnings of Kenyan runners. On this hot Saturday in early June, it seems half of Eldoret has come to shop for groceries at Tusker Mattresses Supermarket. The parking lot across the road is full. People come out, from whole families laden with paper bags branded with the supermarket logo to lone women balancing bags on their heads braving the blistering sun on their long walk home. Tusker Mattresses Supermarket is located on two floors of the five-story Komora Centre, a large building in the middle of town that covers almost an entire city block. It is owned by Moses Kiptanui, the runner who dominated the 3000 m steeplechase races for about five years in the nineties. Kiptanui broke world records, won awards, and the only thing that eluded him was the Olympic gold, which he lost by a razor thin margin to fellow Kenyan Joseph Keter in the 1996 Atlanta games. The steeplechase is special. Even more than other middle and long distance races that have brought Kenyans fame, Kenyan steeplechasers have won all eight times they entered during the last ten Olympics. In 1976 and 1980 Kenya boycotted the Olympics. It is fitting that Kiptanui, one of Kenya’s most successful athletes, is now one of the largest athlete-investors in Eldoret. Eldoret is experiencing a property boom, with growth rates of almost 8%, three times the national average. The changing skyline shows the continuing investment of runners in commercial real estate. -

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics – Men's 800M

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics – Men’s 800m (880yards before 1970) All time performance list at the Commonwealth Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 1:43.22 Steve Cram GBR 1 Edinburgh 1986 2 2 1:43.82 Japheth Kimutai KEN 1 Kuala Lumpur 1998 3 3 1:43.91 John Kipkurgat KEN 1 Christchurch 1974 4 1:44.38 John Kipkurgat 1sf1 Christchurch 1974 5 4 1:44.39 Mike Boit KEN 2 Christchurch 1974 6 5 1:44.44 Hezekiel Sepeng RSA 2 Kuala Lumpur 1998 7 6 1:44.57 Johan Botha RSA 3 Kuala Lumpur 1998 8 7 1:44.80 Tom McKean SCO 2 Edinburgh 1986 9 8 1:44.92 John Walker NZL 3 Christchurch 1974 10 9 1:45.18 Peter Bourke AUS 1 Brisbane 1982 10 9 1:45.18 Patrick Konchellah KEN 1 Victoria 1994 10 9 1:45.18 Savieri Ngidhi ZIM 4 Kuala Lumpur 1998 13 12 1:45.32 Filbert Bayi TAN 4 Christchurch 1974 14 1:45.40 Mike Boit 1sf2 Christchurch 1974 15 13 1:45.42 Peter Elliott ENG 3 Edinburgh 1986 16 14 1:45.45 James Maina Boi KEN 2 Brisbane 1982 17 15 1:45.57 Andy Carter ENG 2sf1 Christchurch 1974 18 16 1:45.60 Chris McGeorge ENG 3 Brisbane 1982 19 17 1:45.71 Andy Hart ENG 5 Kuala Lumpur 1998 20 1:45.76 Hezekiel Sepeng 2 Victoria 1994 21 18 1:45.86 Pat Scammell AUS 4 Edinburgh 1986 22 19 1:45.88 Alex Kipchirchir KEN 1 Melbourne 2006 23 1:45.97 Andy Carter 5 Christchurch 1974 24 20 1:45.98 Sammy Tirop KEN 1 Auckland 1990 25 21 1:46.00 Nixon Kiprotich KEN 2 Auckland 1990 26 1:46.06 Savieri Ngidhi 3 Victoria 1994 27 22 1:46.12 William Serem KEN 1h1 Victoria 1994 28 1:46.15 John Walker 2sf2 Christchurch 1974 29 23 1:46.23 Daniel Omwanza KEN 3sf1 Christchurch -

Newsletter 2020

NEWSLETTER 2020 POOVAMMA ENJOYING TRANSITION TO SENIOR STATESMAN ROLE IN DYNAMIC RELAY SQUAD M R Poovamma has travelled a long way from being the baby of the Indian athletics contingent in the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing to being the elder FEATURED ATHLETE statesman in the 2018 Asian Games in Jakarta. She has experienced the transition, slipping into the new role MR Poovamma (Photo: 2014 Incheon Asian Games @Getty) effortlessly and enjoying the process, too. “It has been a different experience over the past couple of years. Till 2017, I was part of a squad that had runners who were either as old as me or a couple of years older. But now, most of the girls in the team are six or seven years younger than I am,” she says from Patiala. “On the track they see me as a competitor but outside, they look up to me like a member of their family.” The lockdown, forced by the Covid-19 outbreak, and the aftermath have given her the opportunity to don the leadership mantle. “For a couple of months, I managed the workout of the other girls. I enjoyed the role assigned to me,” says the 30-year-old. “We were able to maintain our fitness even during lockdown.” Poovamma reveals that the women’s relay squad trained in the lawn in the hostel premises. “It was a change off the track. We hung out together. It was not like it was a punishment, being forced to stay away from the track and the gym. Our coaches and Athletics Federation of India President Adille (Sumariwalla) sir and (Dr. -

Course Records Course Records

Course records Course records ....................................................................................................................................................................................202 Course record split times .............................................................................................................................................................203 Course record progressions ........................................................................................................................................................204 Margins of victory .............................................................................................................................................................................206 Fastest finishers by place .............................................................................................................................................................208 Closest finishes ..................................................................................................................................................................................209 Fastest cumulative races ..............................................................................................................................................................210 World, national and American records set in Chicago ................................................................................................211 Top 10 American performances in Chicago .....................................................................................................................213 -

List of All Olympics Winners in Kenya

Location Year Player Sport Medals Event Results London 2012 Sally Jepkosgei KIPYEGO Athletics Silver 10000m 30:26.4 London 2012 Vivian CHERUIYOT Athletics Bronze 10000m 30:30.4 London 2012 Abel Kiprop MUTAI Athletics Bronze 3000m steeplechase 08:19.7 London 2012 Ezekiel KEMBOI Athletics Gold 3000m steeplechase 08:18.6 London 2012 Vivian CHERUIYOT Athletics Silver 5000m 15:04.7 London 2012 Thomas Pkemei LONGOSIWA Athletics Bronze 5000m 13:42.4 London 2012 David Lekuta RUDISHA Athletics Gold 800m 1:40.91 London 2012 Timothy KITUM Athletics Bronze 800m 1:42.53 London 2012 Priscah JEPTOO Athletics Silver marathon 02:23:12 London 2012 Wilson Kipsang KIPROTICH Athletics Bronze marathon 02:09:37 London 2012 Abel KIRUI Athletics Silver marathon 02:08:27 Beijing 2008 Micah KOGO Athletics Bronze 10000m 27:04.11 Beijing 2008 Nancy Jebet LAGAT Athletics Gold 1500m 04:00.2 Beijing 2008 Asbel Kipruto KIPROP Athletics Gold 1500m 03:33.1 Beijing 2008 Eunice JEPKORIR Athletics Silver 3000m steeplechase 9:07.41 Beijing 2008 Brimin Kiprop KIPRUTO Athletics Gold 3000m steeplechase 08:10.3 Beijing 2008 Richard Kipkemboi MATEELONG Athletics Bronze 3000m steeplechase 08:11.0 Beijing 2008 Edwin Cheruiyot SOI Athletics Bronze 5000m 13:06.22 Beijing 2008 Eliud Kipchoge ROTICH Athletics Silver 5000m 13:02.80 Beijing 2008 Janeth Jepkosgei BUSIENEI Athletics Silver 800m 01:56.1 Beijing 2008 Wilfred BUNGEI Athletics Gold 800m 01:44.7 Beijing 2008 Pamela JELIMO Athletics Gold 800m 01:54.9 Beijing 2008 Alfred Kirwa YEGO Athletics Bronze 800m 01:44.8 Beijing 2008 Samuel -

Our Part in Four-Minute Mile History

Our part in four-minute mile history Bruce McAvaney addressed a dinner in Melbourne recently, to commemorate Australian John Landy's first sub-four-minute mile and world record, run 50 years ago, six weeks after Roger Bannister first went under four. This is the transcript of his speech. "Here is the result of event No.9, the one mile: No. 41, R G Bannister, of the Amateur Athletic Association and formerly of Exeter and Merton Colleges, with a time that is a new meeting and track record, and which, subject to ratification, with be a new English native, British National, British all-comers, European, British Empire and World Record. The time is 3…." That's arguably the most famous cue, let alone understated announcement in athletics history…3 Minutes, 59.4 seconds! He was a formidable character, the announcer. Norris McWhirter died earlier this year, unfortunately just before the 50th anniversary of the first sub-four minute mile. McWhirter apparently had rehearsed assiduously the night before, in his bath, and it was through him that the BBC, the newsreel camera and most of the print media were present that day. McWhirter, and his twin Ross, who was gunned down in 1975 by the IRA, were joint founders and editors of the Guinness Book of Records. McWhirter had a sense of humour. Here in Melbourne at the 1956 Olympics, he told the story of a middle-aged Australian woman who, observing distressing scenes at the finish of the marathon exclaimed, "Cripes, how many qualify for the final?"… Back to Bannister, and the race: is it the sport's finest achievement? How does the 3.59.4 stack up with other athletic landmarks? Classics such as our own Ron Clarke's 27:39.4 in Oslo in 1965, a 35 second improvement on the previous mark. -

USATF Cross Country Championships Media Handbook

TABLE OF CONTENTS NATIONAL CHAMPIONS LIST..................................................................................................................... 2 NCAA DIVISION I CHAMPIONS LIST .......................................................................................................... 7 U.S. INTERNATIONAL CROSS COUNTRY TRIALS ........................................................................................ 9 HISTORY OF INTERNATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS ........................................................................................ 20 APPENDIX A – 2009 USATF CROSS COUNTRY CHAMPIONSHIPS RESULTS ............................................... 62 APPENDIX B –2009 USATF CLUB NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS RESULTS .................................................. 70 USATF MISSION STATEMENT The mission of USATF is to foster sustained competitive excellence, interest, and participation in the sports of track & field, long distance running, and race walking CREDITS The 30th annual U.S. Cross Country Handbook is an official publication of USA Track & Field. ©2011 USA Track & Field, 132 E. Washington St., Suite 800, Indianapolis, IN 46204 317-261-0500; www.usatf.org 2011 U.S. Cross Country Handbook • 1 HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS USA Track & Field MEN: Year Champion Team Champion-score 1954 Gordon McKenzie New York AC-45 1890 William Day Prospect Harriers-41 1955 Horace Ashenfelter New York AC-28 1891 M. Kennedy Prospect Harriers-21 1956 Horace Ashenfelter New York AC-46 1892 Edward Carter Suburban Harriers-41 1957 John Macy New York AC-45 1893-96 Not Contested 1958 John Macy New York AC-28 1897 George Orton Knickerbocker AC-31 1959 Al Lawrence Houston TFC-30 1898 George Orton Knickerbocker AC-42 1960 Al Lawrence Houston TFC-33 1899-1900 Not Contested 1961 Bruce Kidd Houston TFC-35 1901 Jerry Pierce Pastime AC-20 1962 Pete McArdle Los Angeles TC-40 1902 Not Contested 1963 Bruce Kidd Los Angeles TC-47 1903 John Joyce New York AC-21 1964 Dave Ellis Los Angeles TC-29 1904 Not Contested 1965 Ron Larrieu Toronto Olympic Club-40 1905 W.J. -

All Time Men's World Ranking Leader

All Time Men’s World Ranking Leader EVER WONDER WHO the overall best performers have been in our authoritative World Rankings for men, which began with the 1947 season? Stats Editor Jim Rorick has pulled together all kinds of numbers for you, scoring the annual Top 10s on a 10-9-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1 basis. First, in a by-event compilation, you’ll find the leaders in the categories of Most Points, Most Rankings, Most No. 1s and The Top U.S. Scorers (in the World Rankings, not the U.S. Rankings). Following that are the stats on an all-events basis. All the data is as of the end of the 2019 season, including a significant number of recastings based on the many retests that were carried out on old samples and resulted in doping positives. (as of April 13, 2020) Event-By-Event Tabulations 100 METERS Most Points 1. Carl Lewis 123; 2. Asafa Powell 98; 3. Linford Christie 93; 4. Justin Gatlin 90; 5. Usain Bolt 85; 6. Maurice Greene 69; 7. Dennis Mitchell 65; 8. Frank Fredericks 61; 9. Calvin Smith 58; 10. Valeriy Borzov 57. Most Rankings 1. Lewis 16; 2. Powell 13; 3. Christie 12; 4. tie, Fredericks, Gatlin, Mitchell & Smith 10. Consecutive—Lewis 15. Most No. 1s 1. Lewis 6; 2. tie, Bolt & Greene 5; 4. Gatlin 4; 5. tie, Bob Hayes & Bobby Morrow 3. Consecutive—Greene & Lewis 5. 200 METERS Most Points 1. Frank Fredericks 105; 2. Usain Bolt 103; 3. Pietro Mennea 87; 4. Michael Johnson 81; 5. -

1844 KMS Kenya Past and Present Issue 44

Kenya Past and Present Issue 44 Kenya Past and Present Editor Peta Meyer Editorial Board Marla Stone Kathy Vaughan Patricia Jentz Kenya Past and Present is a publication of the Kenya Museum Society, a not-for-profit organisation founded in 1971 to support and raise funds for the National Museums of Kenya. Correspondence should be addressed to: Kenya Museum Society, PO Box 40658, Nairobi 00100, Kenya. Email: [email protected] Website: www.KenyaMuseumSociety.org Statements of fact and opinion appearing in Kenya Past and Present are made on the responsibility of the author alone and do not imply the endorsement of the editor or publishers. Reproduction of the contents is permitted with acknowledgement given to its source. We encourage the contribution of articles, which may be sent to the editor at [email protected] No category exists for subscription to Kenya Past and Present; it is a benefit of membership in the Kenya Museum Society. Available back issues are for sale at the Society’s offices in the Nairobi National Museum and individual articles can be accessed online at the African Journal Archive: https://journals.co.za/content/collection/african-journal-archive/k Any organisation wishing to exchange journals should write to the Resource Centre Manager, National Museums of Kenya, PO Box 40658, Nairobi 00100, Kenya, or send an email to [email protected] Designed by Tara Consultants Ltd Printed by Kul Graphics Ltd ©Kenya Museum Society Nairobi, June 2017 Kenya Past and Present Issue 44, 2017 Contents The past year at KMS ..................................................................................... 3 Patricia Jentz The past year at the Museum .......................................................................