Our Part in Four-Minute Mile History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tricks of the Trade for Middle Distance, Distance & XC Running

//ÀVÃÊvÊÌ iÊ/À>`iÊvÀÊÀVÃÊvÊÌ iÊ/À>`iÊvÀÊ ``iÊ ÃÌ>Vi]ÊÊ``iÊ ÃÌ>Vi]ÊÊ ÃÌ>ViÊ>`ÊÊ ÃÌ>ViÊ>`ÊÊ ÀÃÃ ÕÌÀÞÊ,Õ} ÀÃÃ ÕÌÀÞÊ,Õ} Ê iVÌÊvÊÌ iÊÊ iÃÌÊ,Õ}ÊÀÌViÃÊvÀÊÊ * ÞÃV>Ê `ÕV>ÌÊ }iÃÌÊ>}>âi ÞÊ VÊÃÃ How to Navigate Within this EBook While the different versions of Acrobat Reader do vary slightly, the basic tools are as follows:. ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Make Page Print Back to Previous Actual Fit in Fit to Width Larger Page Page View Enlarge Size Page Window of Screen Reduce Drag to the left or right to increase width of pane. TOP OF PAGE Step 1: Click on “Bookmarks” Tab. This pane Click on any title in the Table of will open. Click any article to go directly to that Contents to go to that page. page. ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Double click then enter a number to go to that page. Advance 1 Page Go Back 1 Page BOTTOM OF PAGE ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Tricks of the Trade for MD, Distance & Cross-Country Tricks of the Trade for Middle Distance, Distance & Cross-Country Running By Dick Moss (All articles are written by the author, except where indicated) Copyright 2004. Published by Physical Education Digest. All rights reserved. ISBN#: 9735528-0-8 Published by Physical Education Digest. Head Office: PO Box 1385, Station B., Sudbury, Ontario, P3E 5K4, Canada Tel/Fax: 705-523-3331 Email: [email protected] www.pedigest.com U.S. Mailing Address Page 3 Box 128, Three Lakes, Wisconsin, 54562, USA ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Tricks of the Trade for MD, Distance & Cross-Country This book is dedicated to Bob Moss, Father, friend and founding partner. -

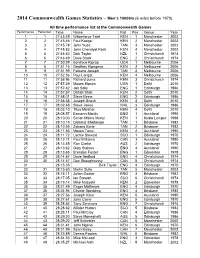

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics – Men's

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics – Men’s 10000m (6 miles before 1970) All time performance list at the Commonwealth Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 27:45.39 Wilberforce Talel KEN 1 Manchester 2002 2 2 27:45.46 Paul Kosgei KEN 2 Manchester 2002 3 3 27:45.78 John Yuda TAN 3 Manchester 2002 4 4 27:45.83 John Cheruiyot Korir KEN 4 Manchester 2002 5 5 27:46.40 Dick Taylor NZL 1 Christchurch 1974 6 6 27:48.49 Dave Black ENG 2 Christchurch 1974 7 7 27:50.99 Boniface Kiprop UGA 1 Melbourne 2006 8 8 27:51.16 Geoffrey Kipngeno KEN 2 Melbourne 2006 9 9 27:51.99 Fabiano Joseph TAN 3 Melbourne 2006 10 10 27:52.36 Paul Langat KEN 4 Melbourne 2006 11 11 27:56.96 Richard Juma KEN 3 Christchurch 1974 12 12 27:57.39 Moses Kipsiro UGA 1 Delhi 2010 13 13 27:57.42 Jon Solly ENG 1 Edinburgh 1986 14 14 27:57.57 Daniel Salel KEN 2 Delhi 2010 15 15 27:58.01 Steve Binns ENG 2 Edinburgh 1986 16 16 27:58.58 Joseph Birech KEN 3 Delhi 2010 17 17 28:02.48 Steve Jones WAL 3 Edinburgh 1986 18 18 28:03.10 Titus Mbishei KEN 4 Delhi 2010 19 19 28:08.57 Eamonn Martin ENG 1 Auckland 1990 20 20 28:10.00 Simon Maina Munyi KEN 1 Kuala Lumpur 1998 21 21 28:10.15 Gidamis Shahanga TAN 1 Brisbane 1982 22 22 28:10.55 Zakaria Barie TAN 2 Brisbane 1982 23 23 28:11.56 Moses Tanui KEN 2 Auckland 1990 24 24 28:11.72 Lachie Stewart SCO 1 Edinburgh 1970 25 25 28:12.71 Paul Williams CAN 3 Auckland 1990 25 26 28:13.45 Ron Clarke AUS 2 Edinburgh 1970 27 27 28:13.62 Gary Staines ENG 4 Auckland 1990 28 28 28:13.65 Brendan Foster ENG 1 Edmonton 1978 29 29 28:14.67 -

© 21St Century Math Projects

© 21st Century Math Projects Project Title: Mile Run Standard Focus: Data Analysis, Patterns, Algebra & Time Range: 3-4 Days Functions Supplies: TI Graphing Technology Topics of Focus: - Scatterplots - Creating and Applying Regression Functions - Interpolation & Extrapolation of Data Benchmarks: 4. For a function that models a relationship between two quantities, interpret key Interpreting F-IF features of graphs and tables in terms of the quantities, and sketch graphs showing key Functions features given a verbal description of the relationship. 6. Calculate and interpret the average rate of change of a function (presented Interpreting F-IF symbolically or as a table) over a specified interval. Estimate the rate of change from a Functions graph.★ Building Functions F-BF 1. Write a function that describes a relationship between two quantities.★ Interpreting 6a. Fit a function to the data; use functions fitted to data to solve problems in the Categorical and S-ID context of the data. Use given functions or choose a function suggested by the context. Quantitative Data Emphasize linear and exponential models. Interpreting Categorical and S-ID 6c. Fit a linear function for a scatter plot that suggests a linear association. Quantitative Data Procedures: A.) Students will use Graphing Calculator Technology to make scatterplots using data from the “Mile Run Chart”. (Graphing Calculator Instructions insert included) B.) Students will complete the three parts of the Mile Run Project. © 21st Century Math Projects The Mile Run In 1593, the English Parliament declared that 5,280 feet would equal 1 mile. Ever since, a mile run has become a staple fitness test everywhere -- from militaries to the high school gyms. -

Housing Problems Force

| PHH ia • THE VIUAMOVAN • Uftmtbw 10. ItTS Football '75 -CLASSIFIED ADS WANTED (Continuedfrom page 10) • > M Bedesem's only reason for a raised self quite capable of handling the rap- eyebrow when talking about the position. Senior Al Buchenauer Earn •xtra monay at homa Undargrad. atudant to HELP WANTED ground, game is to praise it for provides backup. In your apara tima, ad- raaant Qraytiound on cam- Mala or noteworthy improvement. The two linebacker positions draaalng and mailing an- Famala pua. LIbaral commlaalon Ralph Pasquariello is a retur- are in the expert hands of seniors Address envelopes at privllagaa. Datalla home. $800 -I- poaalbia vaiopaa. — lOo ning starter. The sophomore Steve Ramsey and Rick Aldrich. per month, possible. See ad under Contact Mr. Schuti at 568- atamp, Buah, 12240 Grand showed only glimpses of his poten- Business Opportunities. Triple - Ramsey, a co-captain, has seven 0633. < * ffUvar, DatroH, Ml. 48204. "S." tial because he was slowed down career interceptions (high for a I UNIVERSITY, VILLANOVA. PA September 17, 1975 I VILLANOVA by rib injury, which sidelined the LB) and is a definite All-East can- Vol. 51. No. 2 I son of Wildcat rushing • record didate. holder for three weeks. The defensive backfield lost . i . ALL JEWISH The two individuals, however, three starters, but has plenty of STUDENTS who have garnered the most praise candidates for the open positions. are newcomers. Tony Serge, a Steve Ebbecke, a senior co-captain Housing Problems Force Coma to our Hlliol mootlngs sophomore transfer from Army, noted for inspirational play, has •vory Tuosday at 12:30 In tho has impressed all with his speed the safety spot hands down while batomont of Sullivan Hall, and deceptiveness. -

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics–Men's 5000M (3 Mi Before

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics –Men’s 5000m (3 mi before 1970) by K Ken Nakamura All time performance list at the Commonwealth Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 12:56.41 Augustine Choge KEN 1 Melbourne 2006 2 2 12:58.19 Craig Mottram AUS 2 Melbourne 2006 3 3 13:05.30 Benjamin Limo KEN 3 Melbourne 2006 4 4 13:05.89 Joseph Ebuya KEN 4 Melbourne 2006 5 5 13:12.76 Fabian Joseph TAN 5 Melbourne 2006 6 6 13:13.51 Sammy Kipketer KEN 1 Manchester 2002 7 13:13.57 Benjamin Limo 2 Manchester 2002 8 7 13:14.3 Ben Jipcho KEN 1 Christchurch 1974 9 8 13.14.6 Brendan Foster GBR 2 Christchurch 1974 10 9 13:18.02 Willy Kiptoo Kirui KEN 3 Manchester 2002 11 10 13:19.43 John Mayock ENG 4 Manchester 2002 12 11 13:19.45 Sam Haughian ENG 5 Manchester 2002 13 12 13:22.57 Daniel Komen KEN 1 Kuala Lumpur 1998 14 13 13:22.85 Ian Stewart SCO 1 Edinburgh 1970 15 14 13:23.00 Rob Denmark ENG 1 Victoria 1994 16 15 13:23.04 Henry Rono KEN 1 Edmonton 1978 17 16 13:23.20 Phillimon Hanneck ZIM 2 Victoria 1994 18 17 13:23.34 Ian McCafferty SCO 2 Edinburgh 1970 19 18 13:23.52 Dave Black ENG 3 Christchurch 1974 20 19 13:23.54 John Nuttall ENG 3 Victoria 1994 21 20 13:23.96 Jon Brown ENG 4 Victoria 1994 22 21 13:24.03 Damian Chopa TAN 6 Melbourne 2006 23 22 13:24.07 Philip Mosima KEN 5 Victoria 1994 24 23 13:24.11 Steve Ovett ENG 1 Edinburgh 1986 25 24 13:24.86 Andrew Lloyd AUS 1 Auckland 1990 26 25 13:24.94 John Ngugi KEN 2 Auckland 1990 27 26 13:25.06 Moses Kipsiro UGA 7 Melbourne 2006 28 13:25.21 Craig Mottram 6 Manchester 2002 29 27 13:25.63 -

Athletics Records

Best Personal Counseling & Guidance about SSB Contact - R S Rathore @ 9001262627 visit us - www.targetssbinterview.com Athletics Records - 1. 100 Meters Usain Bolt, Jamaica, 9.58. Bolt, who was once a 200-meter specialist, broke the 100-meter world mark for the third time during a thrilling showdown with Tyson Gay at the World Outdoor Championships in Berlin on Aug. 16, 2009. The Jamaican pulled ahead of Gay early in the race and never let up, finishing in 9.58 seconds. The victory came exactly one year after Bolt broke the record for the second time, winning the 2008 Olympic gold medal in 9.69. 2. 200 Meters Usain Bolt, Jamaica, 19.19. Bolt broke his own world mark at the 2009 World Outdoor Track & Field Championships, where he finished in 19.19 seconds on Aug. 20. He first broke Michael Johnson's 12-year-old mark during the Olympic final exactly one year earlier, finishing in 19.30 seconds while running into a slight headwind (0.9 kilometers per hour). 3. 400 Meters Michael Johnson, USA, 43.18. Many expected Johnson to eventually break Butch Reynolds' mark of 43.29 seconds, set in 1988, but 1999 seemed an unlikely year for the record to fall. Johnson suffered from leg injuries that season, missed the U.S. Championships and ran only four 400-meter races before the World Championships (where he gained an automatic entry as the defending champ). By the day of the World final, however, it was apparent that Johnson was in top form and that Reynolds' record was in jeopardy. -

Olympic, World, European and Commonwealth Champion, Greg

Olympic, World, European and Commonwealth champion, Greg Rutherford is Great Britain’s most decorated long jumper and one of the country’s most successful Olympic athletes. After a successful junior career, Greg won gold at the London 2012 Olympics - changing his life forever and playing his part in the most successful night of British olympic sport in history. This iconic victory began a winning streak of gold medals; at the 2014 European Championships, 2014 Commonwealth Games and the 2015 World Championships. In 2015, Greg topped the long jump ranking in the IAAF Diamond League, the athletics equivalent of the Champions League. At the end of his 2015 season, he held every available elite outdoor title. In 2016 at the Rio Olympic’s, Greg backed up his 2012 Olympic success with a further Olympic medal - he also found himself on the Strictly Come Dancing ballroom floor shortly after! Greg is the British record holder, both indoors and outdoors, with bests of 8.26m (indoors) and 8.51m (outdoors). These sporting successes place Greg among the ranks of the British supreme athletics performers - simultaneously holding 4 major outdoors titles - he sits alongside legends such as, Linford Christie, Sally Gunnell, Johnathan Edwards & Daley Thompson. Greg’s route to the top was anything but smooth. From humble and often difficult beginnings, Greg rebelled during his teenage years and ended up dropping out of school, telling his teachers he was going to be a professional sportsman, no matter what - despite having no job, no money and little more than a firm belief in his own raw talent. -

Cor-07-00858

A Reporter’s Guide to Sports and Olympics Reporting Contents Preface 3 Reporting the Olympics 26 Introduction 5 Your role 26 Writing about sport 6 Preparations 26 Accuracy 8 The Games 29 The intro 8 Surviving the mixed zone 30 The match/race report 9 Olympic News Service 30 Quotes and interviews 11 Stars, personalities 32 Some tips on interviewing 15 Reporting the highlights 35 Adding human interest 16 Drugs at the Olympics 35 Features 16 Breaking news stories 36 There are many ways of leading a feature 18 Feature, off-beat, human interest, humorous stories 38 Sponsorship 23 Unusual sports and events 40 Drugs 23 Winter Olympics 40 Some useful websites 24 Tips for the Olympics reporter 42 General sites 24 Photo credits 43 © Reuters 2008. All rights reserved. Reuters and the sphere logo are the trademarks or registered trademarks of the Reuters group of companies around the world. COR-07-00964 Preface During the ancient Olympics, there was a moratorium on wars to allow people across the region to attend the Games. While it is probably too much to expect this to happen today, the ability of sport in general and the Olympic Games in particular to bring countries peacefully together is beyond question. After Cold War boycotts led by Soviet and U.S. teams during the 1980s, the Games have been largely free of political protests since 1988. And in Beijing in 2008, North and South Korea are due to field a joint team for the first time since the peninsula was divided 60 years ago. For journalists covering the Olympics, the task of following their home athletes through 302 different events in 28 sports is challenging enough. -

Welcome WHAT IS IT ABOUT GOLF? EX-GREENKEEPERS JOIN

EX-GREENKEEPERS JOIN HEADLAND James Watson and Steve Crosdale, both former side of the business, as well as the practical. greenkeepers with a total of 24 years experience in "This position provides the ideal opportunity to the industry behind them, join Headland Amenity concentrate on this area and help customers as Regional Technical Managers. achieve the best possible results from a technical Welcome James has responsibility for South East England, perspective," he said. including South London, Surrey, Sussex and Kent, James, whose father retired as a Course while Steve Crosdale takes East Anglia and North Manager in December, and who practised the London including Essex, profession himself for 14 years before moving into WHAT IS IT Hertfordshire and sales a year ago, says that he needed a new ABOUT GOLF? Cambridgeshire. challenge but wanted something where he could As I write the BBC are running a series of Andy Russell, use his experience built programmes in conjunction with the 50th Headland's Sales and up on golf courses anniversary of their Sports Personality of the Year Marketing Director said around Europe. Award with a view to identifying who is the Best of that the creation of these "This way I could the Best. two new posts is take a leap of faith but I Most sports are represented. Football by Bobby indicative of the way the didn't have to leap too Moore, Paul Gascoigne, Michael Owen and David company is growing. Beckham. Not, surprisingly, by George Best, who was James Watson far," he explains. "I'm beaten into second place by Princess Anne one year. -

T Put It Down

In his Foreword, Lord Sebastian Coe eloquently sums up the contents. 'The story Harry tells of Australia at the Olympic Games is as vast and as sweeping as the landscapes of the continent itself, and the world wide Olympic Movement with which Australia shares such a rich history and special bond.' From Athens with Pride chronicles Australia's proud Olympic odyssey from Athens 1896 until Sochi 2014. As Gordon said at the launch, that journey has been ‘laced with some wonderful acts of courage', both individual and collective, collective induding the courage shown by the then Australian Olympic Federation in defying Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser and sending a team of 124 to the boycott-affected Moscow Olympics in 198o. A former general editor of the Australian Dictionary of Biography, John Ritchie, once said of writing biographical material that besides authors thoroughly researching and getting to know their subjects they 'should learn to write like angels'. Harry Gordon has done this in abundance in From Athens with Harry Gordon Pride. Out of interest, during the From Athens w ith Pride writing of the book Gordon, who The Official History of the Australian Olympic first reported the Olympic Games at Movement 1894 to 2014 Helsinki 1952, was inducted into the Penguin Books, Melbourne 2014 336 p.; SA60.00 Melbourne Press Club's prestigious ISBN-13:9780702253348, ISBN-10:072253340 Media Hall of Fame. One of the hitherto untold stories Reviewed by Bruce Coe contained within the pages is that of Francis Gailey. In St. Louis in 1904, 'Once you pick up From Athens Gailey represented the Olympic with Pride you are engrossed, and Club of San Francisco in the swim you are rapt and you just can't put ming events in the man-made it down.' So proclaimed the 1960 lake in Forest Park. -

Factor Analysis of Orld Record Holders in Athletic Decathlon Sport Science 10

Paloić, R. et al.: Factor analysis of orld record holders in athletic decathlon Sport Science 10 (2017) Issue 1: 109-116 FACTOR ANALYSIS OF WORLD RECORD HOLDERS IN ATHLETIC DECATHLON Ratko Pavlović¹ and Kemal Idrizović² University of East Sarajevo, Faculty of Physical Education and Sport, Bosnia and Herzegovina University of Nikšić, Faculty for Sport and Physical Education, Montenegro Original scientific paper Abstract All-around competition is the only competition in which it does not matter whether the athlete is the first, the second or the last in a discipline. What matters is the total number of points, and a rounder competes against his/her personal capabilities and standards. Athletic all-around competitions are a series of consecutive athletic competitions divided in two days. Success is calculated by the sum score of all disciplines that are pointed due to the international athletic tables. The research included ten (10) is currently the world's best decathlete of all time until 2016. Aim of research was to carry out a factor analysis of the athletic decathlon world record holder in order to define factors (latent dimensions) that would determine the type of decathlon, or the so participation technical or motor discipline overall. Applying factor analysis in a defined area is extracted with a total of three factors explained about 75% of the common variance of. The first factor has exhausted 35.24% (pole vault, high jump, discus throw, 400m) and a set of common variance is defined as a type of jumper-thrower-runner. The second factor has exhausted 22.21% (100m; 110m hurdle) analyzed set and is defined as runners (sprinters) type athletes. -

List of All Olympics Winners in Kenya

Location Year Player Sport Medals Event Results London 2012 Sally Jepkosgei KIPYEGO Athletics Silver 10000m 30:26.4 London 2012 Vivian CHERUIYOT Athletics Bronze 10000m 30:30.4 London 2012 Abel Kiprop MUTAI Athletics Bronze 3000m steeplechase 08:19.7 London 2012 Ezekiel KEMBOI Athletics Gold 3000m steeplechase 08:18.6 London 2012 Vivian CHERUIYOT Athletics Silver 5000m 15:04.7 London 2012 Thomas Pkemei LONGOSIWA Athletics Bronze 5000m 13:42.4 London 2012 David Lekuta RUDISHA Athletics Gold 800m 1:40.91 London 2012 Timothy KITUM Athletics Bronze 800m 1:42.53 London 2012 Priscah JEPTOO Athletics Silver marathon 02:23:12 London 2012 Wilson Kipsang KIPROTICH Athletics Bronze marathon 02:09:37 London 2012 Abel KIRUI Athletics Silver marathon 02:08:27 Beijing 2008 Micah KOGO Athletics Bronze 10000m 27:04.11 Beijing 2008 Nancy Jebet LAGAT Athletics Gold 1500m 04:00.2 Beijing 2008 Asbel Kipruto KIPROP Athletics Gold 1500m 03:33.1 Beijing 2008 Eunice JEPKORIR Athletics Silver 3000m steeplechase 9:07.41 Beijing 2008 Brimin Kiprop KIPRUTO Athletics Gold 3000m steeplechase 08:10.3 Beijing 2008 Richard Kipkemboi MATEELONG Athletics Bronze 3000m steeplechase 08:11.0 Beijing 2008 Edwin Cheruiyot SOI Athletics Bronze 5000m 13:06.22 Beijing 2008 Eliud Kipchoge ROTICH Athletics Silver 5000m 13:02.80 Beijing 2008 Janeth Jepkosgei BUSIENEI Athletics Silver 800m 01:56.1 Beijing 2008 Wilfred BUNGEI Athletics Gold 800m 01:44.7 Beijing 2008 Pamela JELIMO Athletics Gold 800m 01:54.9 Beijing 2008 Alfred Kirwa YEGO Athletics Bronze 800m 01:44.8 Beijing 2008 Samuel