Climate Change in the Pacific: Tuvalu Case-Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Action Plan for Implementing the Convention on Biological Diversity's Programme of Work on Protected Areas

Action Plan for Implementing the Convention on Biological Diversity’s Programme of Work on Protected Areas (INSERT PHOTO OF COUNTRY) (TUVALU) Submitted to the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity October 6, 2011 Protected area information: PoWPA Focal Point: Mrs. Tilia Asau Assistant Environment officer-Biodiversity Department of Environment Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Trade, Tourism, Environment & Labour. Government of Tuvalu. Email:[email protected] Lead implementing agency: Department of Environment. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Trade, Tourism, Environment & Labour. Multi-stakeholder committee: Advisory Committee for Tuvalu NBSAP project Description of protected area system National Targets and Vision for Protected Areas Vission: “Keeping in line with the Aichi targets - By the year 2020, Tuvalu would have a clean and healthy environment, full of biological resources where the present and future generations of Tuvalu will continue to enjoy the equitable sharing benefits of Tuvalu’s abundant biological diversity” Mission: “We shall apply our traditional knowledge, together with innovations and best practices to protect our environment, conserve and sustainably use our biological resources for the sustainable benefit of present and future Tuvaluans” Targets: Below are the broad targets for Tuvalu as complemented in the Tuvalu National Biodiversity Action Plan and NSSD. To prevent air, land , and marine pollution To control and minimise invasive species To rehabilitate and restore degraded ecosystems To promote and strengthen the conservation and sustainable use of Tuvalu’s biological diversity To recognize, protect and apply traditional knowledge innovations and best practices in relation to the management, protection and utilization of biological resources To protect wildlife To protect seabed and control overharvesting in high seas and territorial waters Coverage According to World data base on Protected Areas, as on 2010, 0.4% of Tuvalu’s terrestrial surface and 0.2% territorial Waters are protected. -

Basic Design Study Report on the Project for Construction of the Inter-Island Vessel for Outer Island Fisheries Development

BASIC DESIGN STUDY REPORT ON THE PROJECT FOR CONSTRUCTION OF THE INTER-ISLAND VESSEL FOR OUTER ISLAND FISHERIES DEVELOPMENT IN TUVALU January, 2001 Japan International Cooperation Agency Fisheries Engineering Co., Ltd. PREFACE In response to a request from the Government of Tuvalu, the Government of Japan decided to conduct a basic design study on the Project for Construction of the Inter-Island Vessel for Outer Island Fisheries Development in Tuvalu and entrusted the study to the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). JICA sent to Tuvalu a study team from August 1 to August 28, 2000. The team held discussions with the officials concerned of the Government of Tuvalu, and conducted a field study at the study area. After the team returned to Japan, further studies were made. Then, a mission was sent to Tuvalu in order to discuss a draft basic design, and as this result, the present report was finalized. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of the project and to the enhancement of friendly relations between our two countries. I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of the Government of Tuvalu for their close cooperation extended to the teams. January, 2001 Kunihiko Saito President Japan International Cooperation Agency List of Tables and Figures Table 1 Nivaga II Domestic Cargo and Passengers in 1999 ....................................................8 Table 2 Average Passenger Demand by Island Based on Population Ratios .............................9 Table 3 Crew Composition on the Plan Vessel as Compared with the Nivaga II .................... 14 Table 4 Number of Containers Unloaded at Funafuti Port ................................................... -

![Sector Assessment (Summary): Transport (Water Transport [Nonurban])](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5336/sector-assessment-summary-transport-water-transport-nonurban-205336.webp)

Sector Assessment (Summary): Transport (Water Transport [Nonurban])

Outer Island Maritime Infrastructure Project (RRP TUV 48484) SECTOR ASSESSMENT (SUMMARY): TRANSPORT (WATER TRANSPORT [NONURBAN]) Sector Road Map 1. Sector Performance, Problems, and Opportunities 1. Tuvalu is an independent constitutional monarchy in the southwest Pacific Ocean. Formerly known as the Ellice Islands, they separated from the Gilbert Islands after a referendum in 1975, and achieved independence from the United Kingdom on 1 October 1978. The population of 10,100 live on Tuvalu’s nine atolls, which have a total land area of 27 square kilometers. 1 The nine islands, from north to south, are Nanumea, Niutao, Nanumaga, Nui, Vaitupu, Nukufetau, Funafuti, Nukulaelae, and Niulakita. 2. About 43% of the population lives on the outer islands. The small land mass, combined with infertile soil, create a heavy reliance on the sea. The primary economic activities are fishing and subsistence farming, with copra being the main export. 3. The effectiveness and efficiency of maritime transport is highly correlated and integral to the economic development of Tuvalu. Government-owned ships are the only means of transport among the islands. The government fleet includes three passenger and cargo ships operated by the Ministry of Communication and Transport (MCT), a research boat under the Fishery Department, and a patrol boat. 2 The passenger and cargo ships travel from Funafuti to the outer islands and Fiji, so each island only has access to these ships once every 2–3 weeks. Table 1 shows the passengers and cargo carried by the ships in recent years. In addition to the regular services, these ships are used for medical evacuations. -

Questionnaire: Tuvalu 1. Description 1.1 Name(S) of Society, Language, and Language Family: Tuvalu, Tuvaluan, Tuvalu Is in the Austronesian Language Family (1)

Questionnaire: Tuvalu 1. Description 1.1 Name(s) of society, language, and language family: Tuvalu, Tuvaluan, Tuvalu is in the Austronesian language family (1) 1.2 ISO code (3 letter code from ethnologue.com): TVL (1) 1.3 Location (latitude/longitude): The latitude and longitude for Tuvalu are 8 00’S 178 00’E (2) 1.4 Brief history: “The first settlers were from Samoa and probably arrived in the 14th century ad. Niulakita, the smallest and southernmost island, was uninhabited before European contact; the other islands were settled by the 18th century, giving rise to the name Tuvalu, or “Cluster of Eight.” Europeans first discovered the islands in the 16th century through the voyages of Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira, but it was only from the 1820s, with visits by whalers and traders, that they were reliably placed on European charts. In 1863 labor recruiters from Peru kidnapped some 400 people, mostly from Nukulaelae and Funafuti, reducing the population of the group to less than 2,500. Concern over labor recruiting and a desire for protection helps to explain the enthusiastic response to Samoan pastors of the London Missionary Society who arrived in the 1860s. By 1900, Protestant Christianity was firmly established. With imperial expansion the group, then known as the Ellice Islands, became British protectorate in 1892 and part of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony in 1916. There was a gradual expansion of government services, but most administration was through island governments supervised by a single district officer based in Funafuti. Ellice Islanders sought education and employment at the colonial capital in the Gilbert group or in the phosphate industry at Banaba or Nauru. -

Regionalism, Security & Cooperation in Oceania

Regionalism, Security & Cooperation in Oceania Edited by Rouben Azizian and Carleton Cramer Regionalism, Security & Cooperation in Oceania Edited by Rouben Azizian and Carleton Cramer First published June 2015 Published by the Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies 2058 Maluhia Road Honolulu, HI 96815 www.apcss.org For reprint permissions, contact the editors via: [email protected] ISBN 978-0-9719416-7-0 Printed in the United States of America. Vanuatu Harbor Photo used with permission ©GlennCraig Group photo by: Philippe Metois Maps used with permission from: Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) Center for Pacific Island Studies (CPIS) University of Hawai’i at Manoa This book is dedicated to the people of Vanuatu who are recovering from the devastating impact of Cyclone Pam, which struck the country on March 13, 2015. 2 Regionalism, Security & Cooperation in Oceania Table of Contents Acknowledgments and Disclaimers .............................................. 4 List of Abbreviations and Glossary ............................................... 6 Introduction: Regionalism, Security and Cooperation in Oceania Rouben Azizian .............................................................................. 9 Regional Security Architecture in the Pacific 1 Islands Region: Rummaging through the Blueprints R.A. Herr .......................................................................... 17 Regional Security Environment and Architecture in the Pacific Islands Region 2 Michael Powles ............................................................... -

Solomon Islands: Summary Report Educational Experience Survey Education, Language and Literacy Experience About Asia South Pacific Education Watch Initiative

Asia-South Pacific Education Watch Solomon Islands: Summary Report Educational Experience Survey Education, Language and Literacy Experience About Asia South Pacific Education Watch Initiative The critical state and ailing condition of education in many countries in Asia-South Pacific region compels serious and urgent attention from all education stakeholders. Centuries of neglect, underinvestment in education, corrup- tion, and inefficiency by successive governments in the countries of the region have left a grim toll in poor education performance marked by low school attendance and survival rates, high dropout and illiteracy rates, and substandard education quality. Moreover, there are glaring disparities in access to education and learning opportunities: hundreds of millions of impover- ished and disadvantaged groups which include out-of-school chil- dren and youth, child workers, children in conflict areas, women, ethnic minorities, persons with disabilities, dalit caste and other socially discriminated sectors, remain largely unreached and ex- cluded by the education system. Hence they are denied their fundamental human right to edu- cation and hindered from availing of the empowering and trans- formative tool of quality, life-long learning that could have equipped them to realize their full human potential, uplift their living conditions, and participate meaningfully in governance and in decisions that affect their lives. At Midway: Failing Grade in EFA In the year 2000, governments and the international commu- nity affirmed their commitment to quality Education for All (EFA) and Millenium Develoment Goals (MDGs). Midway to target year 2015, government assessments of EFA progress re- veal that education gaps and disparities persist, and education conditions may even be worsening as indicated by shortfalls and reversals in EFA achievement. -

Metronome Trip 1 to Nanumea, Nanumaga and Niutao, 18 June - 4 July 2016

Tuvalu Fisheries Department: Coastal Section: Trip Report Metronome Trip 1 to Nanumea, Nanumaga and Niutao, 18 June - 4 July 2016 Lale Petaia, Semese Alefaio, Tupulaga Poulasi, Viliamu Petaia, Filipo Makolo, Paeniu Lopati, Manuao Taufilo, Maani Petaia, Simeona Italeli, Leopold Paeniu, Tetiana Panapa, Aso Veu 9th August 2016 The mission After nearly a month of preparation, the mission to fulfil the first metronome trip under the NAPA II project was made to the three northern islands (Niutao, Nanumea & Nanumaga). The team mission includes several fisheries officers from both the coastal and the Operational and Development division, two NAPA II officers and three other staffs from other government departments. The full list of the team is provided on the appendix. Although, there were many target activities conducted during this mission, however, the focus of this report is to highlight specific activities that were undertaken specifically by the coastal division staffs during this trip. The overall objective of the mission is to implement fisheries related activities under component 1 of the NAPA II project. These are; I. House hold surveys on socio-economic data II. Collection of Ciguatera data III. Run creel survey trials IV. Canoe and boat survey V. LMMA work VI. Collection of fishery information and data The mission departed Funafuti on 18th June, and return on 4th July. The first island to visit was Niutao, where we stayed for 9 days. The visit to Niutao was the longest out of the three islands due to the unexpected problem we encounter during our stay on the island which will be mention later on this report. -

Pacific Community 2015 Results Report Sustainable Pacific Development Through Science, Knowledge and Innovation

Pacific Community 2015 Results Report Sustainable Pacific development through science, knowledge and innovation Pacific Community│[email protected]│www.spc.int Headquarters: Noumea, New Caledonia Pacific Community 2015 Results Report © Pacific Community (SPC) 2016 All rights for commercial/for profit reproduction or translation, in any form, reserved. SPC authorises the partial reproduction or translation of this material for scientific, educational or research purposes, provided that SPC and the source document are properly acknowledged. Permission to reproduce the document and/or translate in whole, in any form, whether for commercial/for profit or non-profit purposes, must be requested in writing. Original SPC artwork may not be altered or separately published without permission. Original text: English Pacific Community Cataloguing-in-publication data Pacific Community 2015 Results Report / Pacific Community 1. Pacific Community 2. Technical assistance — Oceania. 3. International organization — Oceania. I. Title II. Pacific Community 341.2460995 AACR2 ISBN : 978-982-00-1014-7 Prepared for publication and produced at the headquarters of the Pacific Community Noumea, New Caledonia www.spc.int 2016 Foreword On behalf of the Pacific Community, I am pleased to present this report on our results for 2015 – a year in which we supported our members in meeting some very real challenges. This is the second results report that SPC has produced. The inaugural report for 2013‒2014 launched our efforts to describe not only our scientific and technical work, but also how the results of this work contribute to our members’ achievement of their development goals. The report serves the key purpose of accountability to our members and development partners. -

Giant Swamp Taro, a Little-Known Asian-Pacific Food Crop Donald L

36 TROPICAL ROOT CROPS SYMPOSIUM Martin, F. W., Jones, A., and Ruberte, R. M. A improvement of yams, Dioscorea rotundata. wild Ipomoea species closely related to the Nature, 254, 1975, 134-135. sweet potato. Ec. Bot. 28, 1974,287-292. Sastrapradja, S. Inventory, evaluation and mainte Mauny, R. Notes historiques autour des princi nance of the genetic stocks at Bogor. Trop. pales plantes cultiVl!es d'Afrique occidentale. Root and Tuber Crops Tomorrow, 2, 1970, Bull. Inst. Franc. Afrique Noir 15, 1953, 684- 87-89. 730. Sauer, C. O. Agricultural origins and dispersals. Mukerjee, I., and Khoshoo, T. N. V. Genetic The American Geogr. Society, New York, 1952. evolutionary studies in starch yielding Canna Sharma, A. K., and de Deepesh, N. Polyploidy in edulis. Gen. Iber. 23, 1971,35-42. Dioscorea. Genetica, 28, 1956, 112-120. Nishiyama. I. Evolution and domestication of the Simmonds, N. W. Potatoes, Solanum tuberosum sweet potato. Bot. Mag. Tokyo, 84, 1971, 377- (Solanaceae). In Simmonds, N. W., ed., Evolu 387. tion of crop plants. Longmans, London, 279- 283, 1976. Nishiyama, I., Miyazaki, T., and Sakamoto, S. Stutervant, W. C. History and ethnography of Evolutionary autoploidy in the sweetpotato some West Indian starches. In Ucko, J. J., and (Ipomea batatas (L). Lam.) and its preogenitors. Dimsley, G. W., eds., The domestication of Euphytica 24, 1975, 197-208. plants and animals. Duckworth, London, 177- Plucknett, D. L. Edible aroids, A locasia, Colo 199, 1969. casia, Cyrtosperma, Xanthosoma (Araceae). In Subramanyan, K. N., Kishore, H., and Misra, P. Simmonds, N. W., ed., Evolution of crop plants. Hybridization of haploids of potato in the plains London, 10-12, 1976. -

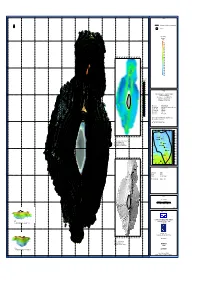

Nanumanga Tuvalu Bathymetry

414000 E 416000 E 418000 E 420000 E 422000 E 424000 E 426000 E 428000 E 430000 E 432000 E 434000 E LEGEND 150 Bathymetric contours shown at 20 metre intervals Land area Colour Banding Bathymetry Metres 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 420000 421000 422000 423000 424000 425000 426000 427000 428000 429000 1000 1100 1200 1300 1400 1500 1600 1700 1800 1900 2000 2100 Slope angle (degrees) 80 75 70 65 60 NOTES 55 Observed soundings have been reduced to Chart Datum 50 defined as 0.7859 m below LAT, 45 1.985 m below mean sea level (MSL 1993-1994), 40 and 4.0123 m below the fixed height of Benchmark 22 on Funafuti, Tuvalu 35 30 25 Date of Survey 08/09 to 24/10/2004 20 Acquisition system Reson SeaBat 8160 multibeam echosounder Collection software Hypack 4.3 15 Processing software Hypack 4.3A 10 Data presentation Surfer 8.03 5 Survey vessel M.V. Turagalevu 0 Backdrop image is a 2003 IKONOS satellite image rectified using differential GPS ground control points. NOT TO BE USED FOR NAVIGATION LOCATION 0 m 4° S 500 m 1000 m 9298000 9299000 9300000 9301000 9302000 9303000 9304000 9305000 9306000 9307000 9308000420000 9309000 9310000 9311000 9312000 9313000 421000 422000 423000 424000 425000 426000 427000 428000 429000 9298000 9299000 9300000 9301000 9302000 9303000 9304000 9305000 9306000 9307000 9308000 9309000 9310000 9311000 9312000 9313000 Nanumea 6° S 1500 m INSET Nanumanga Niutao Gradient slope angle map generated from 20 m 2000 m gridded multibeam bathymetry. Nui Red indicates higher slope angles. -

In Vivo Screening of Salinity Tolerance in Giant Swamp Taro (Cyrtosperma Merkusii)

CSIRO PUBLISHING The South Pacific Journal of Natural and Applied Sciences, 32, 33-36, 2014 www.publish.csiro.au/journals/spjnas 10.1071/SP14005 In vivo screening of salinity tolerance in Giant Swamp Taro (Cyrtosperma merkusii) Shiwangni Rao1, Mary Taylor2 and Anjeela Jokhan1 1Faculty of Science, Technology & Environment, The University of the South Pacific, Suva, Fiji. 2Centre for Pacific Crops & Trees, Secretariat of the Pacific Community, Suva, Fiji. Abstract Giant Swamp Taro (Cyrtosperma merkusii) is a staple food crop in the Pacific, especially in the low lying atoll islands such as Tuvalu and Kiribati. This is owing to its ability to survive under poor soil conditions and harsh environments. However, as a result of the effects of climate change such as sea water inundation and intrusion into the fresh ground water lens, this crop is now under threat. To address this issue an adaption approach was taken whereby, Cyrtosperma merkusii was screened in vivo for salt tolerance. The epistemology followed random selection of two cultivars Ikaraoi and Katutu. These two cultivars were subjected to 0% (0 parts per trillion), 0.5% (5 ppt), 1% (10 ppt), 1.5% (15 ppt) and 2% (20 ppt) of salt in Yates’s advance seedling common potting mix. Both cultivars were able to tolerate salinity levels up-to 5ppt which is significantly more than the salt tolerance in glycophytes of 2.83 ppt. This research provides an insight into the variation of salt tolerance that may exist in C.merkusii gene pool, which can be used to adapt to natural disasters and buffer its impacts. -

Tuvalu Tropical Cyclone Pam Situation Report No. 3.Pdf

Tuvalu: Tropical Cyclone Pam Situation Report No. 3 (as of 9 April 2015) This report is produced by the OCHA Regional Office for the Pacific (ROP) in collaboration with the Government of Tuvalu and the Pacific Humanitarian Team. It covers the period from 27 to 31 March 2015. Highlights The highlights below are based on the information from the central, northern and southern islands for the period 27-31 March 2015. The report includes new information from the agriculture and health teams that visited the northern and southern islands and public works team in Nui. • A total of 39 homes were totally destroyed (12 in Nui Island, 15 in Nanumea, and 12 in Nanumanga). • The Nanumanga clinic suffered severe infrastructure damage. • The clinic in Niutao Island was partially damaged. • Eleven graves in Nanumea Island were damaged, resulting in human remains being brought to the surface. • There are reports of increased mosquito and fly breeding and a strong stench from decaying organic matter in all six affected islands. • The Aedes Egypti mosquito, a known carrier of Dengue fever, was identified in the northern islands of Nanumea, Nanumanga and Niutao. • Communities are depending on canned food as home food production has been compromised by saltwater intrusion. • DFAT and MFAT have committed resources (funds) to support crop replanting and fisheries in the outer islands. • The state of emergency for TC Pam has been lifted. • A French military plane delivered emergency supplies including the school back packs from UNICEF that were awaiting delivery in Nadi, Fiji. • Teams of Red Cross Volunteers have been on the forefront of emergency response in the affected islands distributing emergency supplies and creating awareness on public health and hygiene as well as clean-up operations.