Slow-Moving and Far-Travelled Dense Pyroclastic Flows During the Peach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Source to Surface Model of Monogenetic Volcanism: a Critical Review

Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on September 28, 2021 Source to surface model of monogenetic volcanism: a critical review I. E. M. SMITH1 &K.NE´ METH2* 1School of Environment, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand 2Volcanic Risk Solutions, Massey University, Palmerston North 4442, New Zealand *Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Small-scale volcanic systems are the most widespread type of volcanism on Earth and occur in all of the main tectonic settings. Most commonly, these systems erupt basaltic magmas within a wide compositional range from strongly silica undersaturated to saturated and oversatu- rated; less commonly, the spectrum includes more siliceous compositions. Small-scale volcanic systems are commonly monogenetic in the sense that they are represented at the Earth’s surface by fields of small volcanoes, each the product of a temporally restricted eruption of a composition- ally distinct batch of magma, and this is in contrast to polygenetic systems characterized by rela- tively large edifices built by multiple eruptions over longer periods of time involving magmas with diverse origins. Eruption styles of small-scale volcanoes range from pyroclastic to effusive, and are strongly controlled by the relative influence of the characteristics of the magmatic system and the surface environment. Gold Open Access: This article is published under the terms of the CC-BY 3.0 license. Small-scale basaltic magmatic systems characteris- hazards associated with eruptions, and this is tically occur at the Earth’s surface as fields of small particularly true where volcanic fields are in close monogenetic volcanoes. These volcanoes are the proximity to population centres. -

Anatomy of a Volcanic Eruption: Case Study: Mt. St. Helens

Anatomy of a Volcanic Eruption: Case Study: Mt. St. Helens Materials Included in this Box: • Teacher Background Information • 3-D models of Mt. St. Helens (before and after eruption) • Examples of stratovolcano rock products: Tuff (pyroclastic flow), pumice, rhyolite/dacite, ash • Sandbox crater formation exercise • Laminated photos/diagrams Teacher Background There are several shapes and types of volcanoes around the world. Some volcanoes occur on the edges of tectonic plates, such as those along the ‘ring of fire’. But there are also volcanoes that occur in the middle of tectonic plates like the Yellowstone volcano and Kilauea volcano in Hawaii. When asked to draw a volcano most people will draw a steeply sided, conical mountain that has a depression (crater) at the top. This image of a 'typical' volcano is called a stratovolcano (a.k.a. composite volcano). While this is the often visualized image of a volcano, there are actually many different shapes volcanoes can be. A volcano's shape is mostly determined by the type of magma/lava that is created underneath it. Stratovolcanoes get their shape because of the thick, sticky (viscous) magma that forms at subduction zones. This magma/lava is layered between ash, pumice, and rock fragments. These layers of ash and magma will build into high elevation, steeply sided, conical shaped mountains and form a 'typical' volcano shape. Stratovolcanoes are also known for their explosive and destructive eruptions. Eruptions can cause clouds of gas, ash, dust, and rock fragments to eject into the atmosphere. These clouds of ash can become so dense and heavy that they quickly fall down the side of the volcanoes as a pyroclastic flow. -

Pyroclastic Flow Hazards

Pyroclastic Flow Hazards Lecture Objectives -definition and characteristics -generation of pyroclastic flows -impacts and hazards What are pyroclastic flows? Pyroclastic flows are high- density mixtures of hot, dry rock fragments and hot gases that move away from the vent that erupted them at high speeds. Generation Mechanisms: -explosive eruption of molten or solid rock fragments, or both. -non-explosive eruption of lava when parts of dome or a thick lava flow collapses down a steep slope. Most pyroclastic flows consist of two parts: a basal flow of coarse fragments that moves along the ground, and a turbulent cloud of ash that rises above the basal flow. Ash may fall from this cloud over a wide area downwind from the pyroclastic flow. Mt. St. Helens Effects of pyroclastic flows A pyroclastic flow will destroy nearly everything in its path. With rock fragments ranging in size from ash to boulders traveling across the ground at speeds typically greater than 80 km per hour, pyroclastic flows knock down, shatter, bury or carry away nearly all objects and structures in their way. The extreme temperatures of rocks and gas inside pyroclastic flows, generally between 200°C and 700°C, can cause combustible material to burn, especially petroleum products, wood, vegetation, and houses. Pyroclastic flows vary considerably in size and speed, but even relatively small flows that move <5 km from a volcano can destroy buildings, forests, and farmland. On the margins of pyroclastic flows, death and serious injury to people and animals may result from burns and inhalation of hot ash and gases. Pyroclastic flows generally follow valleys or other low-lying areas and, depending on the volume of rock debris carried by the flow, they can deposit layers of loose rock fragments to depths ranging from less than one meter to more than 200 m. -

The Science Behind Volcanoes

The Science Behind Volcanoes A volcano is an opening, or rupture, in a planet's surface or crust, which allows hot magma, volcanic ash and gases to escape from the magma chamber below the surface. Volcanoes are generally found where tectonic plates are diverging or converging. A mid-oceanic ridge, for example the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, has examples of volcanoes caused by divergent tectonic plates pulling apart; the Pacific Ring of Fire has examples of volcanoes caused by convergent tectonic plates coming together. By contrast, volcanoes are usually not created where two tectonic plates slide past one another. Volcanoes can also form where there is stretching and thinning of the Earth's crust in the interiors of plates, e.g., in the East African Rift, the Wells Gray-Clearwater volcanic field and the Rio Grande Rift in North America. This type of volcanism falls under the umbrella of "Plate hypothesis" volcanism. Volcanism away from plate boundaries has also been explained as mantle plumes. These so- called "hotspots", for example Hawaii, are postulated to arise from upwelling diapirs with magma from the core–mantle boundary, 3,000 km deep in the Earth. Erupting volcanoes can pose many hazards, not only in the immediate vicinity of the eruption. Volcanic ash can be a threat to aircraft, in particular those with jet engines where ash particles can be melted by the high operating temperature. Large eruptions can affect temperature as ash and droplets of sulfuric acid obscure the sun and cool the Earth's lower atmosphere or troposphere; however, they also absorb heat radiated up from the Earth, thereby warming the stratosphere. -

Preliminary Volcano-Hazard Assessment for Augustine Volcano, Alaska

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Preliminary Volcano-Hazard Assessment for Augustine Volcano, Alaska by Christopher F. Waythomas and Richard B. Waitt Open-File Report 98-106 This report is preliminary and subject to revision as new data become available. Any use of trade, product or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey Alaska Volcano Observatory Anchorage, Alaska 1998 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas J. Casadevall, Acting Director For additional information: Copies of this report may be purchased from: U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Alaska Volcano Observatory Branch of Information Services 4200 University Drive Box 25286 Anchorage, AK 99508 Denver, CO 80225-0286 CONTENTS Summary of hazards at Augustine Volcano....................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................... 3 Purposeandscope ...................................................... 3 Physical setting of Augustine Volcano ...................................... 4 Relation to previous studies on Augustine hazards ............................. 5 Prehistoric eruptive history ................................................... 5 Historical eruptions ......................................................... 8 Hazardous phenomena at Augustine Volcano ..................................... 8 Volcanic hazards ....................................................... 12 Volcanicashclouds -

Explosive Eruptions

Explosive Eruptions -What are considered explosive eruptions? Fire Fountains, Splatter, Eruption Columns, Pyroclastic Flows. Tephra – Any fragment of volcanic rock emitted during an eruption. Ash/Dust (Small) – Small particles of volcanic glass. Lapilli/Cinders (Medium) – Medium sized rocks formed from solidified lava. – Basaltic Cinders (Reticulite(rare) + Scoria) – Volcanic Glass that solidified around gas bubbles. – Accretionary Lapilli – Balls of ash – Intermediate/Felsic Cinders (Pumice) – Low density solidified ‘froth’, floats on water. Blocks (large) – Pre-existing rock blown apart by eruption. Bombs (large) – Solidified in air, before hitting ground Fire Fountaining – Gas-rich lava splatters, and then flows down slope. – Produces Cinder Cones + Splatter Cones – Cinder Cone – Often composed of scoria, and horseshoe shaped. – Splatter Cone – Lava less gassy, shape reflects that formed by splatter. Hydrovolcanic – Erupting underwater (Ocean or Ground) near the surface, causes violent eruption. Marr – Depression caused by steam eruption with little magma material. Tuff Ring – Type of Marr with tephra around depression. Intermediate Magmas/Lavas Stratovolcanoes/Composite Cone – 1-3 eruption types (A single eruption may include any or all 3) 1. Eruption Column – Ash cloud rises into the atmosphere. 2. Pyroclastic Flows Direct Blast + Landsides Ash Cloud – Once it reaches neutral buoyancy level, characteristic ‘umbrella cap’ forms, & debris fall. Larger ash is deposited closer to the volcano, fine particles are carried further. Pyroclastic Flow – Mixture of hot gas and ash to dense to rise (moves very quickly). – Dense flows restricted to valley bottoms, less dense flows may rise over ridges. Steam Eruptions – Small (relative) steam eruptions may occur up to a year before major eruption event. . -

Canadian Volcanoes, Based on Recent Seismic Activity; There Are Over 200 Geological Young Volcanic Centres

Volcanoes of Canada 1 V4 C.J. Hickson and M. Ulmi, Jan. 3, 2006 • Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics Where do volcanoes occur? Driving forces • Volcano chemistry and eruption types • Volcanic Hazards Pyroclastic flows and surges Lava flows Ash fall (tephra) Lahars/Debris Flows Debris Avalanches Volcanic Gases • Anatomy of an Eruption – Mt. St. Helens • Volcanoes of Canada Stikine volcanic belt Presentation Outline Anahim volcanic belt Wells Gray – Clearwater volcanic field 2 Garibaldi volcanic belt • USA volcanoes – Cascade Magmatic Arc V4 Volcanoes in Our Backyard Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics In Canada, British Columbia and Yukon are the host to a vast wealth of volcanic 3 landforms. V4 How many active volcanoes are there on Earth? • Erupting now about 20 • Each year 50-70 • Each decade about 160 • Historical eruptions about 550 Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics • Holocene eruptions (last 10,000 years) about 1500 Although none of Canada’s volcanoes are erupting now, they have been active as recently as a couple of 4 hundred years ago. V4 The Earth’s Beginning Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics 5 V4 The Earth’s Beginning These global forces have created, mountain Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics ranges, continents and oceans. 6 V4 continental crust ic ocean crust mantle Where do volcanoes occur? Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics 7 V4 Driving Forces: Moving Plates Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics 8 V4 Driving Forces: Subduction Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics 9 V4 Driving Forces: Hot Spots Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics 10 V4 Driving Forces: Rifting Global Volcanism and Plate tectonics Ocean plates moving apart create new crust. -

2. a Unique Volcanic Field in Tharsis, Mars: Pyroclastic Cones As Evidence for Explosive Eruptions

2. A unique volcanic field in Tharsis, Mars: Pyroclastic cones as evidence for explosive eruptions Petr Brož1,2 and Ernst Hauber3 1Institute of Geophysics ASCR, v.v.i., Prague, Czech Republic 2Institute of Petrology and Structural Geology, Faculty of Science, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic 3Institute of Planetary Research, DLR, Berlin, Germany Status: Published in Icarus 218(1), doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2011.11.030. 2.0. Abstract Based on theoretical grounds, explosive basaltic volcanism should be common on Mars, yet the available morphological evidence is sparse. We test this hypothesis by investigating a unique unnamed volcanic field north of the shield volcanoes Biblis Patera and Ulysses Patera on Mars, where we observe several small conical edifices and associated lava flows. Twenty-nine volcanic cones are identified and the morphometry of many of these edifices is determined using established morphometric parameters such as basal width, crater width, height, slope, and their respective ratios. Their morphology, morphometry, and a comparison to terrestrial analogs suggest that they are martian equivalents of terrestrial pyroclastic cones, the most common volcanoes on Earth. The cones are tentatively interpreted as monogenetic volcanoes. According to absolute model age determinations, they formed in the Amazonian period. Our results indicate that these pyroclastic cones were formed by explosive activity. The cone field is superposed on an old, elevated window of fractured crust which survived flooding by younger lava flows. It seems possible that a more explosive eruption style was common in the past, and that wide-spread effusive plain-style volcanism in the Late Amazonian has buried much of its morphological evidence in Tharsis. -

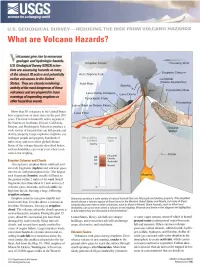

What Are Volcano Hazards?

USGS science for a changing world U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY REDUCING THE RISK FROM VOLCANO HAZARDS What are Volcano Hazards? \7olcanoes give rise to numerous T geologic and hydrologic hazards. Eruption Cloud Prevailing Wind U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) scien tists are assessing hazards at many Eruption Column of the almost 70 active and potentially Ash (Tephra) Fall active volcanoes in the United Landslide (Debris Avalanche) States. They are closely monitoring Acid Rain Bombs activity at the most dangerous of these Pyroclastic Flow volcanoes and are prepared to issue Lava Dome Collapse x Lava Dome warnings of impending eruptions or Pyroclastic Flow other hazardous events. Lahar (Mud or Debris Flow)jX More than 50 volcanoes in the United States Lava Flow have erupted one or more times in the past 200 years. The most volcanically active regions of the Nation are in Alaska, Hawaii, California, Oregon, and Washington. Volcanoes produce a wide variety of hazards that can kill people and destroy property. Large explosive eruptions can endanger people and property hundreds of miles away and even affect global climate. Some of the volcano hazards described below, such as landslides, can occur even when a vol cano is not erupting. Eruption Columns and Clouds An explosive eruption blasts solid and mol ten rock fragments (tephra) and volcanic gases into the air with tremendous force. The largest rock fragments (bombs) usually fall back to the ground within 2 miles of the vent. Small fragments (less than about 0.1 inch across) of volcanic glass, minerals, and rock (ash) rise high into the air, forming a huge, billowing eruption column. -

Scenario-Based Pyroclastic Density Current Invasion Maps at Poorly Known Volcanoes: a Case Study from Changbaishan (China/North Korea)

applied sciences Article Scenario-Based Pyroclastic Density Current Invasion Maps at Poorly Known Volcanoes: A Case Study from Changbaishan (China/North Korea) Anna Maria Lombardi 1, Pierdomenico Del Gaudio 1, Zhengfu Guo 2, Maoliang Zhang 2,3, Guoming Liu 4,5, Vincenzo Sepe 1 , Jiaqi Liu 2 and Guido Ventura 1,* 1 Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, 00143 Roma, Italy; [email protected] (A.M.L.); [email protected] (P.D.G.); [email protected] (V.S.) 2 Key Laboratory of Cenozoic Geology and Environment, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100029, China; [email protected] (Z.G.); [email protected] (M.Z.); [email protected] (J.L.) 3 Institute of Surface-Earth System Science, Tianjin University, Tianjin 300072, China 4 Earthquake Administration of Jilin Province, Changchun 130022, China; [email protected] 5 Changbaishan Volcano Observatory, Antu 133613, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 6 March 2020; Accepted: 7 April 2020; Published: 10 April 2020 Featured Application: Volcanic hazard evaluation, Urban Planning. Abstract: Changbaishan volcano (China/North Korea; last eruption in 1903 AD) was responsible for a Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) 7 eruption in 946 AD. Approximately 186,000 people live around Changbaishan and 2,000,000 tourists/year visit the volcano. An unrest occurred between 2002 and 2006. Despite the relevant hazard, the eruptive history is poorly known, a condition common to many volcanoes worldwide. Here, we investigate the extension of the areas potentially affected by pyroclastic density currents (PDCs) in case of future eruptions following a scenario-based approach. -

Blue-Sky Eruptions, Do They Exist? Implications for Monitoring New

Blue‐sky eruptions, do they exist? Implications for monitoring New Zealand’s volcanoes. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Disaster and Hazard Management at the University of Canterbury by Angela Louise Doherty University of Canterbury 2009 Frontispiece “What are the odds, right?” “Before it happened it would have said slim, but since it did happen I would say 100%...” Dr Ray Langston replying to Catherine Willows (played by Lawrence Fishburne and Marg Helgenberger – CSI: Crime Scene Investigation). Lahar following the September 2007 eruption of Ruapehu (photo: GNS Science). Abstract The term “blue‐sky eruption” (BSE) can be used to describe eruptions which are unexpected or have no detected precursory activity. Case study analyses indicate that they have a diverse range of characteristics and magnitudes, providing both direct and indirect hazards and occur in both under‐developed and developed countries. BSEs can be a result of physical triggers (e.g. the lack of physically detectable precursors or a lack of understanding of the eruption model of the volcano), social triggers (such as an inadequate monitoring network), or a combination of the two. As the science of eruption forecasting is still relatively young, and the variations between individual volcanoes and individual eruptions are so great, there is no effective general model and none should be applied in the absence of a site‐specific model. Similarly, as methods vary between monitoring agencies, there are no monitoring benchmarks for effective BSE forecasting. However a combination of seismic and gas emission monitoring may be the most effective. -

A Database of the Economic Impacts of Historical Volcanic Eruptions M Goujon, Hajare El Hadri, Raphael Paris

A database of the economic impacts of historical volcanic eruptions M Goujon, Hajare El Hadri, Raphael Paris To cite this version: M Goujon, Hajare El Hadri, Raphael Paris. A database of the economic impacts of historical volcanic eruptions. 2021. hal-03186803 HAL Id: hal-03186803 https://hal.uca.fr/hal-03186803 Preprint submitted on 31 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. C E N T R E D 'ÉTUDES ET DE RECHERCHES SUR LE DEVELOPPEMENT INTERNATIONAL SÉRIE ÉTUDES ET DOCUMENTS A database of the economic impacts of historical volcanic eruptions Hajare El Hadri Michaël Goujon Raphaël Paris Études et Documents n° 14 March 2021 To cite this document: El Hadri H., Goujon M., Paris R. (2021) “A database of the economic impacts of historical volcanic eruptions ”, Études et Documents, n°14, CERDI. CERDI POLE TERTIAIRE 26 AVENUE LÉON BLUM F- 63000 CLERMONT FERRAND TEL. + 33 4 73 17 74 00 FAX + 33 4 73 17 74 28 http://cerdi.uca.fr/ Études et Documents n°14, CERDI, 2021 The authors Hajare El Hadri Post-doctoral researcher, Université Clermont