THEATRICAL COLLOQUIA Hamlet's Theatre Lesson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tragedy of Hamlet

THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET THE WORKS OF SHAKESPEARE THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET EDITED BY EDWARD DOWDEN n METHUEN AND CO. 36 ESSEX STREET: STRAND LONDON 1899 9 5 7 7 95 —— CONTENTS PAGE Introduction ix The Tragedy of Hamlet i Appendix I. The "Travelling" of the Players. 229 Appendix II.— Some Passages from the Quarto of 1603 231 Appendix III. Addenda 235 INTRODUCTION This edition of Hamlet aims in the first place at giving a trustworthy text. Secondly, it attempts to exhibit the variations from that text which are found in the primary sources—the Quarto of 1604 and the Folio of 1623 — in so far as those variations are of importance towards the ascertainment of the text. Every variation is not recorded, but I have chosen to err on the side of excess rather than on that of defect. Readings from the Quarto of 1603 are occa- sionally given, and also from the later Quartos and Folios, but to record such readings is not a part of the design of this edition. 1 The letter Q means Quarto 604 ; F means Folio 1623. The dates of the later Quartos are as follows: —Q 3, 1605 161 1 undated 6, For ; Q 4, ; Q 5, ; Q 1637. my few references to these later Quartos I have trusted the Cambridge Shakespeare and Furness's edition of Hamlet. Thirdly, it gives explanatory notes. Here it is inevitable that my task should in the main be that of selection and condensation. But, gleaning after the gleaners, I have perhaps brought together a slender sheaf. -

Chapter 4: Acting

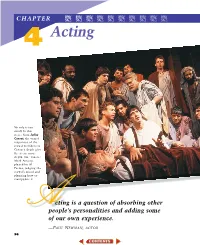

096-157 CH04-861627 12/4/03 12:01 AM Page 96 CHAPTER ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ ᪴ 4 Acting No role is too small. In this scene from Julius Caesar, the varied responses of the crowd members to Caesar’s death give the scene more depth. One can see Mark Antony, played by Al Pacino, judging the crowd’s mood and planning how to manipulate it. cting is a question of absorbing other Apeople’s personalities and adding some of our own experience. —PAUL NEWMAN, ACTOR 96 096-157 CH04-861627 12/4/03 12:02 AM Page 97 SETTING THE SCENE Focus Questions What special terminology is used in acting? What are the different types of roles? How do you create a character? What does it mean to act? Vocabulary emotional or straight parts master gesture subjective acting character parts inflection technical or objective acting characterization subtext leading roles primary source substitution protagonist secondary sources improvisation antagonist body language paraphrasing supporting roles So now you’re ready to act! For most students of drama, this is the moment you have been waiting for. You probably share the dream of every actor to create a role so convincing that the audience totally accepts your character as real, for- getting that you are only an actor playing a part. You must work hard to be an effective actor, but acting should never be so real that the audience loses the theatrical illu- sion of reality. Theater is not life, and acting is not life. Both are illusions that are larger than life. -

Ediţia a 24-A

Ediţia a 24-a Bucureşti 2014 FESTIVALUL NAŢIONAL DE TEATRU Ediţia a 24-a www.fnt.ro PROGRAMUL SPECTACOLELOR ŞI EVENIMENTELOR 24 octombrie - 2 noiembrie BUCUREŞTI2014 „Furtuna” 20.00 Teatrul Naţional LANSĂRI DE CARTE de William Shakespeare „I.L.Caragiale” din Bucureşti Regia: Alexander Morfov Sala Pictură Vineri, 24 octombrie 16.00 Ceainăria ARCUB Produs de: Teatrul Naţional „Noul Locatar” „Scrieri despre teatru” „I.L.Caragiale” din Bucureşti de Eugène Ionesco de Tadeusz Kantor Durata: 3h cu pauză Regia: Mihaela Panainte Editura Teatrul Azi DESCHIDERE Produs de: Teatrul Municipal Cu sprijinul Institutului OFICIALĂ 18.00 şi 20.30 Teatrul Odeon Baia Mare Polonez din Bucureşti Sala Majestic Durata: 55 min fără pauză şi al Editurii Cheiron / VERNISAJ „Viaţa-i mai frumoasă după Bucureşti, 2014 ce mori” 21.30 Teatrul Naţional Textul şi regia: Mihai Măniuţiu „Cetatea literară” (revista) „I.L.Caragiale” din Bucureşti Produs de: Teatrul „Tomcsa Colecţie completă Sâmbătă, 25 octombrie Sala Multimedia Sándor”, Odorheiu Secuiesc în ediţie anastatică Vernisajul expoziţiei Durata: 1h 10 min fără pauză Editura Teatrul Azi „Doina Levintza: Costumul de cu sprijinul Editurii Cheiron teatru – De la schiţă la miracol”* 19.00 Godot Café Teatru EXPOZIŢII Bucureşti, 2014 „Fă-mi loc!” Teatrul Naţional „I.L.Caragiale” Anthony Michineau „Comentarii şi delimitări de din Bucureşti, Sala Mică, foaier SPECTACOLE Regia: Radu Beligan în teatru” „Doina Levintza: Costumul de de Camil Petrescu Produs de: Asociaţia INSPIRA teatru – De la schiţă la miracol”* 18.00 Teatrul Naţional Bucureşti Editura Teatrul Azi „I.L.Caragiale” din Bucureşti Durata: 1h 30 min fără pauză Bucureşti, 2006 Sala Studio „Pe drumul gândirii axiologice” 19.00 Teatrul Metropolis 19.00 Teatrul Naţional Regia: Silviu Purcărete de Gheorghe Ceauşu „Lecţia de violoncel” „I.L. -

STUDY GUIDE Introductiontable of Contentspg

STUDY GUIDE IntroductionTABLE OF CONTENTSPg. 3 Pg. 4 Top Ten Things to Know About Going to the Theatre Cast and Creative Team Credits Pg. 5 Mysterious Shakespeare Pg. 6 Inside Vertigo Theatre- An Interview with Anna Cummer Pg. 8 Pre-Show Projects and Discussion Questions Pg. 10 Ghostly Appearances It's Time To Soliloquize Your Burning Questions Pre-Show Activities- To Get You Up On Your Feet Pg. 15 Making Up Meter The Dumbshow Post Show Discussion Questions Pg. 20 The Art of The Theatre Review Pg. 21 About Vertigo Theatre Pg.22 Vertigo Theatre is committed to creating a welcoming atmosphere for schools and to assisting teachers and parent chaperones with that process. It is our wish to foster and develop our relationship with our student audience members. It is our intention to create positive theatre experiences for young people by providing study guides and post-show talk backs with our actors and theatre personnel, in order to enrich students’ appreciation of theatre as an art form and enhance their enjoyment of our plays. IntroductionWelcome to the Study Guide for Vertigo Theatre's, The Shakespeare Company and Hit & Myth's production of Hamlet: A Ghost Story by William Shakespeare, adapted by Anna Cummer. In this guide you will find information about this new adaptation of Hamlet and Shakespeare’s connection to mystery theatre. It also includes information about the creative team and performers involved in the production, as well as a variety of activities to do with your class before and after the show. There are topics suitable for class discussion, individual writing projects, as well as games and exercises that get students moving around and learning on their feet. -

Speak the Speech: Lessons in Projection, Clarity and Performance

Otterbein University Digital Commons @ Otterbein Masters Theses/Capstone Projects Student Research & Creative Work Spring 5-1-2020 Speak the Speech: Lessons in Projection, Clarity and Performance James Hagerman Otterbein University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/stu_master Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Secondary Education Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hagerman, James, "Speak the Speech: Lessons in Projection, Clarity and Performance" (2020). Masters Theses/Capstone Projects. 47. https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/stu_master/47 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research & Creative Work at Digital Commons @ Otterbein. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses/Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Otterbein. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPEAK THE SPEECH: LESSONS IN PROJECTION, CLARITY AND PERFORMANCE James B. Hagerman Otterbein University MAE Program April 24, 2020 Submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for a Masters of Arts in Education degree. Dr. Dee Knoblauch ____________________________ _____________ Advisor Signature Date Dr. Susan Millsap ___________________________ ______________ Second Reader Signature Date Dr. Bethany Vosburg-Bluem ___________________________ ______________ Third Reader Signature Date SPEAK THE SPEECH Copyright By James B. Hagerman 2020 ii SPEAK THE SPEECH Acknowledgements I would like to offer my sincere thanks to those individuals who inspired and helped me with this study. My professors Dr. Dee Knoblauch, Dr. Susan Millsap, Dr. Bethany Vosburg-Bluem, Dr. Daniel Cho, Dr. Clare Kilbane, Dr. Kristen Bourdage, and my family: Lori and James for supporting me in this endeavor during this year of the coronavirus. -

Studia Politica Nr. 42014

www.ssoar.info Ghiță Ionescu on the BBC Goșu, Armand Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Goșu, A. (2014). Ghiță Ionescu on the BBC. Studia Politica: Romanian Political Science Review, 14(4), 439-468. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-446573 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de Ghi ță Ionescu on the BBC ARMAND GO ŞU On 9 March 1947, Ghi ță Ionescu landed in London. He had a transit visa to “Belgium-France”, bearing the date 24 February 1947 1. He had obtained the visa at the General Consulate of Great Britain in Istanbul, Galata. The British clerk crossed out with his pen “valid for one day” and wrote “one month”. Ghi ță Ionescu had to hurry. On 22 March 1947, his diplomatic passport was set to expire 2. He had its validity extended by the chargé d'affaires at the Romanian legation in Ankara. He had just been recalled by Alexandru Cretzianu, Romania's Minister Plenipotentiary in Turkey. Shortly after, a new ambassador to Ankara was appointed, convenient to the Petru Groza government, which was dominated by communists. Most likely, his chances of carrying on as economic adviser at the Romanian legation in Turkey's capital, and therefore of having his passport renewed, were rather slim, and the political events in Bucharest did not inspire optimism, since Ghi ță Ionescu made meticulous preparations to head over the the West. -

Activity Pack #4: Hamlet

HAMLET | FOOD FOR THOUGHT Shakespeare’s language can seem scary, but give it a try! Go at your own pace, and have fun! The Shakespeare The Translation SHAKESPEARE IN PRISON Hamlet Hamlet Speak the speech, I pray you, as I pronounc’d it to you, Perform the speech just as DETROIT PUBLIC THEATRE'S trippingly on the tongue, but if you mouth it, as many I taught you, musically and SIGNATURE COMMUNITY PROGRAM of our players do, I had as lief the town-crier spoke my smoothly. If you exaggerate lines. Nor do not saw the air too much with your hand, the words the way some thus, but use all gently, for in the very torrent, tempest, actors do, I might as well have some newscaster read and, as I may say, whirlwind of your passion, you must the lines. Don’t use too many hand gestures; just do a acquire and beget a temperance that may give it few, gently, like this. When you get into a whirlwind of smoothness. O, it offends me to the soul to hear a passion on stage, remember to keep the emotion robustuous periwig-pated fellow tear a passion to moderate and smooth. I hate it when I hear a blustery totters, to very rags, to spleet the ears of the actor in a wig tear a passion to shreds, bursting everyone’s eardrums so as to impress the audience on groundlings, who for the most part are capable of the lower levels of the playhouse, who for the most part nothing but inexplicable dumb shows and noise. -

Prof. Dr. MĂNIUȚIU MIHAI PETRE

Universitatea „Babeș-Bolyai” Cluj Napoca Facultatea de Teatru și Televiziune Departamentul de Teatru Prof. dr. MĂNIUȚIU MIHAI PETRE Cărți: 10 volume de ficțiune (proză) și poezie Spectacole montate 2018 La ordin, Führer ! de Brigitte Schwaiger, regia Mihai Măniuțiu. Teatrul Evreiesc de Stat, București Burghezul gentilom de Molière, Teatrul Maghiar de Stat, Cluj 2017 – Cafeneaua Pirandello, după Luigi Pirandello, Teatrul Regina Maria, Oradea – Rambuku de Jon Fosse, Teatrul Național Timișoara - Jurnalul lui Robinson Crusoe, după Gellu Naum, Teatrul Odeon, București 2016 – Goldberg Show. Despre facerea lumii și alte întâmplări, după Variațiunile Goldberg de George Tabori. Tetrul național V. Alecsandri, Iași - Alcool, după Ion Mureșan. Scenariul și regia Mihai Măniuțiu. Teatrul Nottara, București - Iarna de Ion Fosse. Regia Mihai Măniuțiu. Teatrul Nottara, București - La ordin, Führer ! de Brigitte Schwaiger, regia Mihai Măniuțiu. Teatrul Municipal Aureliu Manea Turda. 2015 – Electra Project. Scenariu și regia de Mihai Măniuțiu după Sofocle și Euripide, Claire Trevor Theatre, Department of Drama, Claire Trevor School of the Arts, UC Irvine, SUA. - Vertij de Mihai Măniuțiu. Text, scenariu și regie: Mihai Măniuțiu. Teatrul Municipal Aureliu Manea Turda. - Recviem pentru un spion de George Tabori. Regia Mihai Măniuțiu. Teatrul Maghiar de Stat Cluj. - Meteorul de Friedrich Dürrenmatt, regia Mihai Măniuțiu. Teatrul Național M. Eminescu, Timișoara. - Trei ore după miezul nopții, regia Mihai Măniuțiu, Teatrul Tony Bulandra, Târgoviște. 2014 - Don Quijote, după Miguel de Cervantes, Teatrul Național Târgu-Mureș. - Viața e mai frumoasă dupa ce mori (Szeb az elet hallal utan) de Mihai Măniuțiu, Teatrul Municipal, Odorheiul Secuiesc. - Lecția de E. Ionesco, Teatrul Național Radu Stanca Sibiu. 2013 - Domnul Swedenborg vrea să viseze, text și regie de Mihai Măniuțiu, Teatrul Național Iași. -

Reflectarea Fenomenelor Literare În Presa Românească Între Anii 1990 � 2000

UNIVERSITATEA „DUNĂREA DE JOS” GALAłI FACULTATEA DE LITERE REFLECTAREA FENOMENELOR LITERARE ÎN PRESA ROMÂNEASCĂ ÎNTRE ANII 1990 - 2000 Teză de doctorat - rezumat - Conducător de doctorat, Prof. Univ. Dr. Nicolae IOANA Doctorand, Zanfir Ilie GalaŃi 20 octombrie 2012 CUPRINS 1. CONSIDERAłII GENERALE ASUPRA FENOMENULUI LITERAR ROMÂNESC LA MOMENTUL TRANZIłIEI 1.1. Preliminarii 4 1.2. Prefigurarea schimbării politice şi ideologice. Anticamera libertăŃii de exprimare 9 1.3. Mistificări auto-identitare în contextul schimbării 12 1.4. Literatura română şi presa literară în momentul „decembrie ’89” 16 1.5. Noua presă literară din România. Orientări şi paradigme 22 2. PRINCIPALELE REVISTE CULTURALE. MODELUL CAPITALEI 2.1. Presa literară de tranziŃie. Reviste, directori şi lideri 48 2.2. România literară . Nicolae Manolescu şi implicarea politică 54 2.3. Caiete critice . Eugen Simion şi autonomia esteticului 80 2.4. Contemporanul – Ideea europeană şi Nicolae Breban 97 2.5. Literatorul . Marin Sorescu şi Fănuş Neagu 113 2.6. Dilema şi Andrei Pleşu 132 3. PRESA LITERARĂ DIN PROVINCIE, DIN BASARABIA ŞI DIN NORDUL BUCOVINEI 3.1. EmergenŃa revistelor literare în Ńară 139 3.2. Abordarea literaturii în marile cotidiene 173 3.3. Reviste de limbă română din Chişinău şi din CernăuŃi 180 2 4. TEMELE MAJORE ALE DEZBATERII LITERARE POSTDECEMBRISTE 4.1. Între estetic şi politic. Controverse 191 4.2. GeneraŃii şi promoŃii literare 194 4.3. Critica de întâmpinare şi critica de sinteză 205 4.4. Revizuiri, reevaluări şi restructurări canonice 212 4.5. Spiritul polemic. Contestatari şi detractori 224 5. FENOMENOLOGIA LITERARĂ SUB SEMNUL GLOBALIZĂRII 5.1. Consumul cultural din perspectiva „satului global” 235 5.2. -

Resistance Through Literature in Romania (1945-1989)

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 11-2015 Resistance through literature in Romania (1945-1989) Olimpia I. Tudor Depaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Tudor, Olimpia I., "Resistance through literature in Romania (1945-1989)" (2015). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 199. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/199 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Resistance through Literature in Romania (1945-1989) A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts October, 2015 BY Olimpia I. Tudor Department of International Studies College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences DePaul University Chicago, Illinois Acknowledgements I am sincerely grateful to my thesis adviser, Dr. Shailja Sharma, PhD, for her endless patience and support during the development of this research. I wish to thank her for kindness and generosity in sharing her immense knowledge with me. Without her unconditional support, this thesis would not have been completed. Besides my adviser, I would like to extend my gratitude to Dr. Nila Ginger Hofman, PhD, and Professor Ted Anton who kindly agreed to be part of this project, encouraged and offered me different perspectives that helped me find my own way. -

Download PDF File

18-27 octombrie F NT F NT F NT F NT F NT F NT F NT 2019bucuresti, editia, a 29-a ROMÂNIA Ediţie desfășurată sub Înaltul Patronaj al Președintelui României PREŞEDINTELE ROMÂNIEI 2 F NT F NT F NT F NT F NT F NT F NT Ediţie dedicată celor 30 de ani de la momentul Decembrie 1989 Edition dedicated to the 30 years after December 1989 Teatrul, clipa magicA a istoriei unt treizeci de ani de când România a intrat în pot măsura prin dramele pe care societăţile le pot trăi pe termen libertate și în democraţie. În toţi aceşti ani s-au scurt sau pe termen lung. întâmplat multe lucruri. Ne putem exprima liber, putem crea liber, putem gândi liber, iar noi, Selecţia din acest an urmărește aceleași lucruri care m-au oamenii de cultură, putem fi o forţă și un reper interesat de când am în grijă acest festival. Este pentru a noua pentru societatea noastră. Cultura este, indiferent oară de când fac programul evenimentelor, selecţia spectacolelor S românești și celor străine, și mă îngrijesc de obţinerea finanţărilor de momentele mai bune sau mai grele pe care o societate le traversează, reperul absolut. Ca şi educaţia. Este ceea ce ne duce pentru realizarea proiectului meu. Festivalul îşi propune să arate întotdeauna înainte și mult mai profund în interiorul nostru. ce este semnificativ, nou şi normal într-un interval de timp. În cazul de faţă, stagiunea 2018-2019. Sper ca artiștii să se bucure că În acești treizeci de ani s-au întâmplat și lucruri groaznice. sunt văzuţi pe scenele teatrelor din Capitală. -

The Tragedy of Hamlet by William Shakespeare

The Tragedy of Hamlet By William Shakespeare Act 3, Scene 2 The Tragedy of Hamlet: Act 3, Scene 2 by William Shakespeare SCENE. A hall in the castle. (Enter HAMLET and Players) HAMLET Speak the speech, I pray you, as I pronounced it to you, trippingly on the tongue: but if you mouth it, as many of your players do, I had as lief the town-crier spoke my lines. Nor do not saw the air too much with your hand, thus, but use all gently; for in the very torrent, tempest, and, as I may say, the whirlwind of passion, you must acquire and beget a temperance that may give it smoothness. O, it offends me to the soul to hear a robustious periwig-pated fellow tear a passion to tatters, to very rags, to split the ears of the groundlings, who for the most part are capable of nothing but inexplicable dumbshows and noise: I would have such a fellow whipped for o'erdoing Termagant; it out-herods Herod: pray you, avoid it. First Player I warrant your honour. HAMLET Be not too tame neither, but let your own discretion be your tutor: suit the action to the word, the word to the action; with this special o'erstep not the modesty of nature: for any thing so overdone is from the purpose of playing, whose end, both at the first and now, was and is, to hold, as 'twere, the mirror up to nature; to show virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure.