Translation Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sr. No. College Name University Name Taluka District JD Region

Non-Aided College List Sr. College Name University Name Taluka District JD Region Correspondence College No. Address Type 1 Shri. KGM Newaskar Sarvajanik Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune Pandit neheru Hindi Non-Aided Trust's K.G. College of Arts & Pune University, ar ar vidalaya campus,Near Commerece, Ahmednagar Pune LIC office,Kings Road Ahmednagrcampus,Near LIC office,Kings 2 Masumiya College of Education Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune wable Non-Aided Pune University, ar ar colony,Mukundnagar,Ah Pune mednagar.414001 3 Janata Arts & Science Collge Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune A/P:- Ruichhattishi ,Tal:- Non-Aided Pune University, ar ar Nagar, Dist;- Pune Ahmednagarpin;-414002 4 Gramin Vikas Shikshan Sanstha,Sant Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune At Post Akolner Tal Non-Aided Dasganu Arts, Commerce and Science Pune University, ar ar Nagar Dist Ahmednagar College,Akolenagar, Ahmednagar Pune 414005 5 Dr.N.J.Paulbudhe Arts, Commerce & Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune shaneshwar nagarvasant Non-Aided Science Women`s College, Pune University, ar ar tekadi savedi Ahmednagar Pune 6 Xavier Institute of Natural Resource Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune Behind Market Yard, Non-Aided Management, Ahmednagar Pune University, ar ar Social Centre, Pune Ahmednagar. 7 Shivajirao Kardile Arts, Commerce & Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune Jambjamb Non-Aided Science College, Jamb Kaudagav, Pune University, ar ar Ahmednagar-414002 Pune 8 A.J.M.V.P.S., Institute Of Hotel Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag -

Literatura Orientu W Piśmiennictwie Polskim XIX W

Recenzent dr hab. Kinga Paraskiewicz Projekt okładki Igor Stanisławski Na okładce wykorzystano fragment anonimowego obrazu w stylu kad żarskim „Kobieta trzymaj ąca diadem” (Iran, poł. XIX w.), ze zbiorów Państwowego Muzeum Ermita żu, nr kat. VP 1112 Ksi ąż ka finansowana w ramach programu Ministra Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wy ższego pod nazw ą „Narodowy Program Rozwoju Humanistyki” w latach 2013-2017 © Copyright by individual authors, 2016 ISBN 978-83-7638-926-4 KSI ĘGARNIA AKADEMICKA ul. św. Anny 6, 31-008 Kraków tel./faks 12-431-27-43, 12-421-13-87 e-mail: [email protected] Ksi ęgarnia internetowa www.akademicka.pl Spis tre ści Słowo wst ępne . 7 Ignacy Krasicki, O rymotwórstwie i rymotwórcach. Cz ęść dziewi ąta: o rymotwórcach wschodnich (fragmenty) . 9 § I. 11 § III. Pilpaj . 14 § IV. Ferduzy . 17 Assedy . 18 Saady . 20 Suzeni . 22 Katebi . 24 Hafiz . 26 § V. O rymotwórstwie chi ńskim . 27 Tou-fu . 30 Lipe . 31 Chaoyung . 32 Kien-Long . 34 Diwani Chod ża Hafyz Szirazi, zbiór poezji Chod ży Hafyza z Szyrazu, sławnego rymotwórcy perskiego przez Józefa S ękowskiego . 37 Wilhelm Münnich, O poezji perskiej . 63 Gazele perskiego poety Hafiza (wolny przekład z perskiego) przeło żył Jan Wiernikowski . 101 Józef Szujski, Rys dziejów pi śmiennictwa świata niechrze ścija ńskiego (fragmenty) . 115 Odczyt pierwszy: Świat ras niekaukaskich z Chinami na czele . 119 Odczyt drugi: Aryjczycy. Świat Hindusów. Wedy. Ksi ęgi Manu. Budaizm . 155 Odczyt trzeci: Epopeja indyjskie: Mahabharata i Ramajana . 183 Odczyt czwarty: Kalidasa i Dszajadewa [D źajadewa] . 211 Odczyt pi ąty: Aryjczycy. Lud Zendów – Zendawesta. Firduzi. Saadi. Hafis . 233 Piotr Chmielowski, Edward Grabowski, Obraz literatury powszechnej w streszczeniach i przekładach (fragmenty) . -

Introduction

1 Introduction A jackal who had fallen into a vat of indigo dye decided to exploit his mar- velous new appearance and declared himself king of the forest. He ap- pointed the lions and other animals as his vassals, but took the precaution of having all his fellow jackals driven into exile. One day, hearing the howls of the other jackals in the distance, the indigo jackal’s eyes filled with tears and he too began to howl. The lions and the others, realizing the jackal’s true nature, sprang on him and killed him. This is one of India’s most widely known fables, and it is hard to imagine that anyone growing up in an Indian cultural milieu would not have heard it. The indigo jackal is as familiar to Indian childhood as are Little Red Rid- ing Hood or Snow White in the English-speaking world. The story has been told and retold by parents, grandparents, and teachers for centuries in all the major Indian languages, both classical and vernacular. Versions of the collec- tion in which it first appeared, the Pañcatantra, are still for sale at street stalls and on railway platforms all over India. The indigo jackal and other narratives from the collection have successfully colonized the contemporary media of television, CD, DVD, and the Internet. I will begin by sketching the history and development of the various families of Pañcatantra texts where the story of the indigo jackal first ap- peared, starting with Pu–rnabhadra’s. recension, the version on which this inquiry is based. -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1869 , 01/10/2018 Class 32 1974588 03

Trade Marks Journal No: 1869 , 01/10/2018 Class 32 1974588 03/06/2010 JAYA WATEK INDUSTRIES trading as ;JAYA WATEK INDUSTRIES INDIRA GANDHI ROAD, MONGOLPUR, BALURGHAT,PIN 733103,W.B. MANUFACTURER & MERCHANT AN INDAIN COMPANY Used Since :02/04/2007 KOLKATA PACKGE DRINKING WATER, FRUIT DRINKS AND FRUIT JUICES, SOFT DRINKS, SYRUPSAND OTHER PREPARATIONS FOR MAKING BEVERAGES 5463 Trade Marks Journal No: 1869 , 01/10/2018 Class 32 BEY BLADER 2159631 14/06/2011 HECTOR BEVERAGES PVT. LTD B-82 SOUTH CITY -1 GURGAON 122001 SERVICE PROVIDER AN INCORPORATED COMPANY Address for service in India/Agents address: CHESTLAW H 2/4, MALVIYA NAGAR NEW DELHI-110017 Proposed to be Used DELHI BEVERAGES, NAMELY DRINKING WATERS, FLAVOURED WATERS, MINERAL AND AERATED WATERS AND OTHER NON-ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES, NAMELY SOFT DRINKS, ENERGY DRINKS, AND SPORTS DRINKS, FRUIT DRINKS AND JUICES, SYRUPS, CONCENTRATES AND POWDERS FOR MAKING BEVERAGES, NAMELY FLAVORED WATERS, MINERAL AND AERATED WATERS, SOFT DRINKS, ENERGY DRINKS, SPORTS DRINKS, FRUIT DRINKS AND JUICES; DE- ALCOHOLISED DRINKS AND BEER ETC. 5464 Trade Marks Journal No: 1869 , 01/10/2018 Class 32 PowerPop 2299749 15/03/2012 ESSEN FOODDIES INDIA PVT,LTD. trading as ;ESSEN FOODDIES INDIA PVT,LTD. KINFRA (FOOD) SPECIAL ECONOMIC ZONE, KAKKANCHERY,CHELEMBRA P.O., MALAPPURAM - 673634 KERALA MANUFACTURERS AND MERCHANTS - Address for service in India/Attorney address: ANUP JOACHIM.T CC43/ 1983, SRSRA-2, SANTHIPURAM ROAD, COCHIN-682025,KERALA Proposed to be Used CHENNAI MINERAL AND AERATED WATER, NUTRITION DRINKS, ENERGY DRINKS, PACKAGED DRINKING WATER, FRUIT DRINKS AND FRUIT JUICES, SYRUPS, OTHER NON-ALCOHOLIC DRINKS. 5465 Trade Marks Journal No: 1869 , 01/10/2018 Class 32 2441929 13/12/2012 HIMANSHU BHATT DHIREN BHARAD trading as ;J. -

Abstract 2005

Seminar on Subh¢¾hita, Pa®chatantra and Gnomic Literature in Ancient and Medieval India Saturday, 27th December 2008 ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS ‘Shivshakti’, Dr. Bedekar’s Hospital, Naupada, Thane 400 602 Phone: 2542 1438, 2542 3260 Fax: 2544 2525 e-mail: [email protected] URL : http://www.orientalthane.com 1 I am extremely happy to present the book of abstracts for the seminar “Subhashita, Panchatantra and Gnomic Literature in Ancient and Medieval India”. Institute for Oriental Study, Thane has been conducting seminars since 1982. Various scholars from India and abroad have contributed to the seminars. Thus, we have a rich collection of research papers in the Institute. Indian philosophy and religion has always been topics of interest to the west since opening of Sanskrit literature to the West from late 18th century. Eminent personalities both in Europe and American continents have further contributed to this literature from the way they perceived our philosophy and religion. The topic of this seminar is important from that point of view and almost all the participants have contributed something new to the dialogue. I am extremely thankful to all of them. Dr. Vijay V. Bedekar President Institute for Oriental Study, Thane 2 About Institute Sir/Madam, I am happy to inform you that the Institute for Oriental Study, Thane, founded in 1984 has entered into the 24th year of its existence. The Institute is a voluntary organization working for the promotion of Indian culture and Sanskrit language. The Institute is registered under the Societies Registration Act, 1860 (No.MAH/1124/Thane dated 31st Dec.,1983) and also under the Bombay Public Trusts Act 1950 (No.F/1034/Thane dated 14th March, 1984). -

OLD FLORIDA BOOK SHOP, INC. Rare Books, Antique Maps and Vintage Magazines Since 1978

William Chrisant & Sons' OLD FLORIDA BOOK SHOP, INC. Rare books, antique maps and vintage magazines since 1978. FABA, ABAA & ILAB Facebook | Twitter | Instagram oldfloridabookshop.com Catalogue of Sanskrit & related studies, primarily from the estate of Columbia & U. Pennsylvania Professor Royal W. Weiler. Please direct inquiries to [email protected] We accept major credit cards, checks and wire transfers*. Institutions billed upon request. We ship and insure all items through USPS Priority Mail. Postage varies by weight with a $10 threshold. William Chrisant & Sons' Old Florida Book Shop, Inc. Bank of America domestic wire routing number: 026 009 593 to account: 8981 0117 0656 International (SWIFT): BofAUS3N to account 8981 0117 0656 1. Travels from India to England Comprehending a Visit to the Burman Empire and Journey through Persia, Asia Minor, European Turkey, &c. James Edward Alexander. London: Parbury, Allen, and Co., 1827. 1st Edition. xv, [2], 301 pp. Wide margins; 2 maps; 14 lithographic plates 5 of which are hand-colored. Late nineteenth century rebacking in matching mauve morocco with wide cloth to gutters & gouge to front cover. Marbled edges and endpapers. A handsome copy in a sturdy binding. Bound without half title & errata. 4to (8.75 x 10.8 inches). 3168. $1,650.00 2. L'Inde. Maurice Percheron et M.-R. Percheron Teston. Paris: Fernand Nathan, 1947. 160 pp. Half red morocco over grey marbled paper. Gilt particulars to spine; gilt decorations and pronounced raised bands to spine. Decorative endpapers. Two stamps to rear pastedown, otherwise, a nice clean copy without further markings. 8vo. 3717. $60.00 3. -

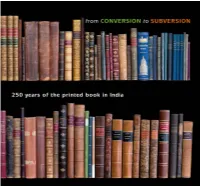

From Conversion to Subversion a Selection.Pdf

2014 FROM CONVERSION TO SUBVERSION: 250 years of the printed book in India 2014 From Conversion to Subversion: 250 years of the printed book in India. A catalogue by Graham Shaw and John Randall ©Graham Shaw and John Randall Produced and published in 2014 by John Randall (Books of Asia) G26, Atlas Business Park, Rye, East Sussex TN31 7TE, UK. Email: [email protected] All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without prior permission in writing of the publisher and copyright holder. Designed by [email protected], Devon Printed and bound by Healeys Print Group, Suffolk FROM CONVERSION TO SUBVERSION: 250 years of the printed book in India his catalogue features 125 works spanning While printing in southern India in the 18th the history of print in India and exemplify- century was almost exclusively Christian and Ting the vast range of published material produced evangelical, the first book to be printed in over 250 years. northern India was Halhed’s A Grammar of the The western technology of printing with Bengal Language (3), a product of the East India movable metal types was introduced into India Company’s Press at Hooghly in 1778. Thus by the Portuguese as early as 1556 and used inter- began a fertile period for publishing, fostered mittently until the late 17th century. The initial by Governor-General Warren Hastings and led output was meagre, the subject matter over- by Sir William Jones and his generation of great whelmingly religious, and distribution confined orientalists, who produced a number of superb to Portuguese enclaves. -

Modern-Baby-Names.Pdf

All about the best things on Hindu Names. BABY NAMES 2016 INDIAN HINDU BABY NAMES Share on Teweet on FACEBOOK TWITTER www.indianhindubaby.com Indian Hindu Baby Names 2016 www.indianhindubaby.com Table of Contents Baby boy names starting with A ............................................................................................................................... 4 Baby boy names starting with B ............................................................................................................................. 10 Baby boy names starting with C ............................................................................................................................. 12 Baby boy names starting with D ............................................................................................................................. 14 Baby boy names starting with E ............................................................................................................................. 18 Baby boy names starting with F .............................................................................................................................. 19 Baby boy names starting with G ............................................................................................................................. 19 Baby boy names starting with H ............................................................................................................................. 22 Baby boy names starting with I .............................................................................................................................. -

Gaudiya Math in Austria Keykey Elements of Cost for the Future, Based on the fi Nancial Support Received

Sriman Mahaprabhu and His Mission Who established the Sri Krishna Chaitanya Mission? audiya Vaishnavism is a spiritual move- e Modern Era he founder acharya of Sri After taking sannyas in 1940, He has started the Sri ment founded by Sri Krishna Chaitanya As time passed, the theology and practice of this Krishna Chaitanya Mission Krishna Chaitanya Mission in India. While preaching the Sri Sri Radha Govinda Gaudiya Math GMahaprabhu in India in the 15th century. pure devotional line were buried in ignorance and T is Om Vishnupada Srila message of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu he established 26 ‘Gaudiya’ refers to the Gaudiya region (present misconceptions. At this precarious time, in 1838 B.V. Puri Gosvami. He appeared in Gaudiya Maths in India, Italy, Spain, Mexico and Austria, day West Bengal/Bangladesh) with Vaishnavism Srila Bhaktivinoda akur was born in Birnagar in 1913 in a small village in Berham- additionally initiating thousands of disciples in the chant- NEW TEMPLE PROJECT meaning ‘ e worship of Vishnu (Krishna)’. Its the district of Nadia in West Bengal. After coming pur district, Orissa, India. After ing of the Holy Name. philosophical basis are Bhagavad Gita, Srimad in contact with the life and teachings of Sri Chait- completing his study of Ayurveda Bhagavatam as well as other puranic scriptures anya Mahaprabhu he focused all his activities on he opened a hospital and simul- Present Acharya in Austria and the Upanishads. Sri Krishna Chaitanya Ma- Sri Krishna Chaitanya the study and distribution of Mahaprabhu’s mes- taneously led Gandhi’s freedom Before he left this world he Mahaprabhu haprabhu (1486–1534) is the Yuga Avatar of Su- sage. -

Shakespeare in Gujarati: a Translation History

Shakespeare in Gujarati: A Translation History SUNIL SAGAR Abstract Translation history has emerged as one of the most significant enterprises within Translation Studies. Translation history in Gujarati per se is more or less an uncharted terrain. Exploring translation history pertaining to landmark authors such as Shakespeare and translation of his works into Gujarati could open up new vistas of research. It could also throw new light on the cultural and historical context and provide new insights. The paper proposes to investigate different aspects of translation history pertaining to Shakespeare’s plays into Gujarati spanning nearly 150 years. Keywords: Translation History, Methodology, Patronage, Poetics. Introduction As Anthony Pym rightly (1998: 01) said that the history of translation is “an important intercultural activity about which there is still much to learn”. This is why history of translation has emerged as one of the key areas of research all over the world. India has also taken cognizance of this and initiated efforts in this direction. Reputed organizations such as Indian Institute of Advanced Study (IIAS) and Central Institute of Indian Languages (CIIL) have initiated discussion and discourse on this area with their various initiatives. Translation history has been explored for some time now and it’s not a new area per se. However, there has been a paradigm shift in the way translation history is approached in the recent times. As Georges L. Bastin and Paul F. Bandia (2006: 11) argue in Charting the Future of Translation History: Translation Today, Volume 13, Issue 2 Sunil Sagar While much of the earlier work was descriptive, recounting events and historical facts, there has been a shift in recent years to research based on the interpretation of these events and facts, with the development of a methodology grounded in historiography. -

Three Women Sants of Maharashtra: Muktabai, Janabai, Bahinabai

Three Women Sants of Maharashtra Muktabai, Janabai, Bahinabai by Ruth Vanita Page from a handwritten manuscript of Sant Bahina’s poems at Sheor f”kÅj ;sFkhy gLrfyf[kukP;k ,dk i~’Bkpk QksVks NUMBER 50-51-52 (January-June 1989) An ant flew to the sky and swallowed the sun Another wonder - a barren woman had a son. A scorpion went to the underworld, set its foot on the Shesh Nag’s head. A fly gave birth to a kite. Looking on, Muktabai laughed. -Muktabai- 46 MANUSHI THE main trends in bhakti in Maharashtra is the Varkari tradition which brick towards Krishna for him to stand on. Maharashtra took the form of a number of still has the largest mass following. Krishna stood on the brick and was so sant traditions which developed between Founded in the late thirteenth and early lost in Pundalik’s devotion that he forgot the thirteenth and the seventeenth fourteenth centuries1 by Namdev (a sant to return to heaven. His wife Rukmani had centuries. The sants in Maharashtra were of the tailor community, and Jnaneshwar, to come and join him in Pandharpur where men and women from different castes and son of a socially outcasted Brahman) who she stands as Rakhumai beside Krishna in communities, including Brahmans, wrote the famous Jnaneshwari, a versified the form of Vitthal (said to be derived from Vaishyas, Shudras and Muslims, who commentary in Marathi on the Bhagwad vitha or brick). emphasised devotion to god’s name, to Gita, the Varkari (pilgrim) tradition, like the The Maharashtrian sants’ relationship the guru, and to satsang, the company of Mahanubhav, practises nonviolence and to Vitthal is one of tender and intimate love. -

The Evolution of the Printed Bengali Character

The Evolution of the Printed Bengali Character from 1778 to 1978 by Fiona Georgina Elisabeth Ross School of Oriental and African Studies University of London Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1988 ProQuest Number: 10731406 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ProQuest 10731406 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 20618054 2 The Evolution of the Printed Bengali Character from 1778 to 1978 Abstract The thesis traces the evolution of the printed image of the Bengali script from its inception in movable metal type to its current status in digital photocomposition. It is concerned with identifying the factors that influenced the shaping of the Bengali character by examining the most significant Bengali type designs in their historical context, and by analyzing the composing techniques employed during the past two centuries for printing the script. Introduction: The thesis is divided into three parts according to the different methods of type manufacture and composition: 1. The Development of Movable Metal Types for the Bengali Script Particular emphasis is placed on the early founts which lay the foundations of Bengali typography.