Education in Rutland in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries Pp.38-48

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Church Wing Burley-On-The-Hill, Rutland

Church Wing Burley-on-the-Hill, Rutland Church Wing Burley-on-the-Hill, Rutland, LE15 7FH Oakham 2 miles, Stamford 11 miles, Peterborough 20 miles (London Kings Cross 50 minutes), Leicester 20 miles. (All distances and times are approximate) A Magnificent Wing within one of the Finest Grade I Listed, 18th Century Palladian Mansions in the Country • Hall • Cloakroom • The Long Room • Breakfast Kitchen • Principal Bedroom with En Suite Shower Room • Spiral Staircase to Dressing Room/Gym, Walk-in Wardrobe • Office • Church Passage • Stairs down to: • Sitting Room • Boot Room • 4 Bedrooms • 2 Bathrooms • Utility/Washing Room • Services Closet • Private South Facing Garden • Double Garage, Driveway and Parking Use of Approximately 67 Acres of Parkland, Gardens and Deer Park St Mary’s Street, Stamford 36 High Street, Oakham Lincolnshire, PE9 2DE Leicestershire, LE15 6AL Tel: 01780 484520 Tel: 01572 757979 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] www. kingwest .co.uk www. mooresestateagents .com Land & Estate Agents • Commercial • Town Planning & Development Consultants Offices – London • Market Harborough • Stamford These particulars are intended as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of facts. Your attention is drawn to the important notice at the back of this brochure. History The Domesday Book of 1086 mentions this splendid hilltop £25,000 and eventually spiraled to more than £80,000 and site, then held by Ulf, and a house has stood here for many necessitated the sale of Kensington House, the Earl’s centuries. In 1603 King James VI of Scotland stayed at Burley property in London, to King William III for £18,000. -

Hay Any Work for Cooper 1 ______

MARPRELATE TRACTS: HAY ANY WORK FOR COOPER 1 ________________________________________________________________________________ Hay Any Work For Cooper.1 Or a brief pistle directed by way of an hublication2 to the reverend bishops, counselling them if they will needs be barrelled up3 for fear of smelling in the nostrils of her Majesty and the state, that they would use the advice of reverend Martin for the providing of their cooper. Because the reverend T.C.4 (by which mystical5 letters is understood either the bouncing parson of East Meon,6 or Tom Cook's chaplain)7 hath showed himself in his late Admonition To The People Of England to be an unskilful and beceitful8 tub-trimmer.9 Wherein worthy Martin quits himself like a man, I warrant you, in the modest defence of his self and his learned pistles, and makes the Cooper's hoops10 to fly off and the bishops' tubs11 to leak out of all cry.12 Penned and compiled by Martin the metropolitan. Printed in Europe13 not far from some of the bouncing priests. 1 Cooper: A craftsman who makes and repairs wooden vessels formed of staves and hoops, as casks, buckets, tubs. (OED, p.421) The London street cry ‘Hay any work for cooper’ provided Martin with a pun on Thomas Cooper's surname, which Martin expands on in the next two paragraphs with references to hubs’, ‘barrelling up’, ‘tub-trimmer’, ‘hoops’, ‘leaking tubs’, etc. 2 Hub: The central solid part of a wheel; the nave. (OED, p.993) 3 A commodity commonly ‘barrelled-up’ in Elizabethan England was herring, which probably explains Martin's reference to ‘smelling in the nostrils of her Majesty and the state’. -

Groundwater in Jurassic Carbonates

Groundwater in Jurassic carbonates Field Excursion to the Lincolnshire Limestone: Karst development, source protection and landscape history 25 June 2015 Tim Atkinson (University College London) with contributions from Andrew Farrant (British Geological Survey) Introduction 1 The Lincolnshire Limestone is an important regional aquifer. Pumping stations at Bourne and other locations along the eastern edge of the Fens supply water to a large population in South Lincolnshire. Karst permeability development and rapid groundwater flow raise issues of groundwater source protection, one of themes of this excursion. A second theme concerns the influence of landscape development on the present hydrogeology. Glacial erosion during the Middle Pleistocene re-oriented river patterns and changed the aquifer’s boundary conditions. Some elements of the modern groundwater flow pattern may be controlled by karstic permeability inherited from pre-glacial conditions, whereas other flow directions are a response to the aquifer’s current boundary conditions. Extremely high permeability is an important feature in part of the confined zone of the present-day aquifer and the processes that may have produced this are a third theme of the excursion. The sites to be visited will demonstrate the rapid groundwater flow paths that have been proved by water tracing, whereas the topography and landscape history will be illustrated by views during a circular tour from the aquifer outcrop to the edge of the Fenland basin and back. Quarry exposures will be used to show the karstification of the limestone, both at outcrop and beneath a cover of mudrock. Geology and Topography The Middle Jurassic Lincolnshire Limestone attains 30 m thickness in the area between Colsterworth and Bourne and dips very gently eastwards. -

Listado De Internados En Inglaterra

INGLATERRA COLEGIOS INTERNADOS PRECIOS POR TERM (4 MESES) MÁS DE 350 COLEGIOS Tarifas oficiales de los colegios internados añadiendo servicio de tutela en Inglaterra registrado en AEGIS a partir de £550 por term cumpliendo así con la legislación inglesa actual y con el estricto código de buenas prácticas de estudiantes internacionales Precio 1 Term Ranking Precio 1 Term Ranking Abbey DLD College London £8,350 * Boundary Oak School £7,090 * Abbots Bromley School £9,435 290 Bournemouth Collegiate £9,100 382 Abbotsholme School £10,395 * Box Hill School £10,800 414 Abingdon School £12,875 50 Bradfield College £11,760 194 Ackworth School £8,335 395 Brandeston Hall £7,154 * ACS Cobham £12,840 * Bredon School £9,630 * Adcote School £9,032 356 Brentwood School £11,378 195 Aldenham School £10,482 * Brighton College £13,350 6 Aldro School £7,695 * Bromsgrove School £11,285 121 Alexanders College £9,250 0 Brooke House College £9,900 * Ampleforth College £11,130 240 Bruton School for Girls £9,695 305 Ardingly College £10,710 145 Bryanston School £11,882 283 Ashbourne College £8,250 0 Burgess Hill School for Girls £10,150 112 Ashford School £11,250 254 Canford School £11,171 101 Ashville College £9,250 355 Casterton Sedbergh Prep £7,483 * Badminton School £11,750 71 Caterham School £10,954 65 Barnard Castle School £8,885 376 Catteral Hall £7,400 * Barnardiston Hall Prep £6,525 * Cheltenham College £11,865 185 Battle Abbey School £9,987 348 Chigwell School £9,310 91 Bede's £11,087 296 Christ College Brecon £8,994 250 Bede's Prep School £8,035 * Christ's -

Clipsham Farm, Clipsham, Rutland Clipsham Farm, Clipsham, Planing Consent Has Been Obtained for a New Grain Store in Field Number 8345

Clipsham Farm, Clipsham, Rutland Clipsham Farm, Clipsham, Planing consent has been obtained for a new grain store in field number 8345. This can be Rutland viewed on South Kesteven District Council’s website under planning reference: S17/2084. An attractive and undulating arable Further information is available from the farm with an opportunity to develop a vendor’s agent. range of traditional buildings. Barn conversion Stamford 7 miles, Oakham 11 miles, Grantham 15 Planning consent has been granted for the miles conversion of existing agricultural buildings into a four bedroom dwelling and a one bedroom Planning consent for a four bedroom barn annex. The barns are located in the centre of conversion and a seperate annex | 391.31 acres the property and benefit from views across the of arable land | 117.46 acres of pasture farm. This can be viewed on Rutland County 37.66 acres of woodland | Exciting sporting Council's website under planning reference: opportunities with a well-established shoot 2020/0674/FUL. About 554.27 acres (224 hectares) in total For Sporting sale as a whole Clipsham Farm benefits from rolling landscape, mature woodland and strategically placed game Situation covers which produce an enjoyable and exciting Clipsham Farm is located on the border partridge and pheasant shoot. There are also of Rutland and Lincolnshire about 7 miles muntjac and fallow deer on the farm which offer north of the market town of Stamford. There interesting stalking opportunities. is good shopping, recreational and leisure facilities locally in Stamford, Peterborough and General Grantham. The property is well connected with Method of sale Peterborough and Grantham both providing Clipsham Farm is offered for sale with vacant excellent regular direct rail links to London. -

The Best Place to Live ….. ….For Everyone?

Rutland - the best place to live ….. ….for everyone? A Report on Poverty in Rutland 2016 Barbara Coulson BA., MA Cantab., MA Nottingham CONTENTS Executive Summary ........................................................................................... 2 Citizens Advice Rutland .................................................................................... 5 Why a Rutland rural poverty report? ........................................................... 6 IntroductiIntroductionononon .....................................................................................................6 Defining Poverty ..............................................................................................7 Rutland and Rural Poverty ..............................................................................9 Measuring PoPovertyverty and Deprivation in Rutland .......................................... 11 The Determinants of Poverty - Income Deprivation .............................. 13 The Determinants of Poverty - High Costs ................................................ 18 Housing and Associated Costs .....................................................................18 Fuel Costs and Fuel Poverty ..........................................................................24 Food Poverty .................................................................................................29 Transport and Poverty ..................................................................................32 Poverty as it affects people .......................................................................... -

Rutland County Council Electoral Review Submission on Warding Patterns

Rutland County Council Electoral Review Submission on Warding Patterns INTRODUCTION 1. The Council presented a Submission on Council Size to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England (LGBCE) on 11 July 2017 following approval at Full Council. On 25 July the LGBCE wrote to the Council advising that it was minded to recommend that 26 County Councillors should be elected to Rutland County Council in future in accordance with the Council’s submission. 2. The second stage of the review concerns warding arrangements. The Council size will be used to determine the average (optimum) number of Electors per councillor to be achieved across all wards of the authority. This number is reached by dividing the electorate by the number of Councillors on the authority. The LGBCE initial consultation on Warding Patterns takes place between 25 July 2017 and 2 October 2017. 3. The Constitution Review Working Group is Cross Party member group. The terms of reference for the Constitution Review Working Group (CRWG) (Agreed at Annual Council 8 May 2017) provide that the working group will review arrangements, reports and recommendations arising from Boundary and Community Governance reviews. Therefore, the CRWG undertook to develop a proposal on warding patterns which would then be presented to Full Council on 11 September 2017 for approval before submission to the LGBCE. BACKGROUND 4. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England technical guidance states that an electoral review will be required when there is a notable variance in representation across the authority. A review will be initiated when: • more than 30% of a council’s wards/divisions having an electoral imbalance of more than 10% from the average ratio for that authority; and/or • one or more wards/divisions with an electoral imbalance of more than 30%; and • the imbalance is unlikely to be corrected by foreseeable changes to the electorate within a reasonable period. -

Guide Michelin Eating out in Pubs 2013

INFORMATION PRESSE Boulogne, le 1 er novembre 2012 GUIDE MICHELIN EATING OUT IN PUBS 2013 L’édition 2013 du guide MICHELIN Eating Out in Pubs sera disponible en librairie et en ligne dès le vendredi 2 novembre au prix de 13,99 livres (16,99 euros en Irlande). Cette année, le guide recense plus de 550 pubs, dont 81 nouveaux établissements, situés dans tout le Royaume-Uni, depuis Kylesku en Écosse jusqu'à Perranuthnoe et Southwolt en Angleterre en passant par Cahersiveen en Irlande. Sous la direction de Michael Ellis, Directeur du guide MICHELIN, cette sélection montre que la qualité de la cuisine proposée dans les pubs ne cesse de s’améliorer, et que de plus en plus d'établissements choisissent de servir en priorité des produits régionaux. De nombreux pubs parviennent à relever le défi du rapport qualité-prix : « Les chefs n'hésitent plus à utiliser des pièces moins nobles afin de composer des menus à des prix plus abordables, notamment pour le déjeuner, souligne la rédactrice en chef du guide Rebecca Burr. Ils se montrent aussi plus souples que par le passé et acceptent plus facilement d'échanger les menus du bar et du restaurant. Certains établissements commencent même à proposer des petits-déjeuners, des brunchs et des pauses goûter l’après-midi.» Preuve de l’amélioration permanente de la qualité, deux nouveaux pubs se voient attribuer des étoiles MICHELIN cette année : le Hinds Head de Heston Blumenthal à Bray et le Red Lion Freehouse dirigé par Guy et Britt Manning, à East Chisenbury. Ces récompenses confirment que le Royaume-Uni dispose non seulement d'un solide patrimoine culinaire, mais compte également un grand nombre de chefs très talentueux et créatifs, qu’ils soient aux fourneaux ou propriétaires de pubs. -

Speaker Information 2019 WLSA Global Educators Conference

Speaker information 2019 WLSA Global Educators Conference Page | 1 Gail BERSON Title: Director of College Counseling Institution: Lycée Français de New York Biography: Gail Berson is the Director of College Counseling at the Lycée Français de New York. She has more than 40 years of experience in college admission, student financial services, and counseling. A magna cum laude graduate of Bowdoin College, she earned her master’s degree at Emerson College. She served as Vice President for Enrollment/Dean of Admissions. n and Financial Aid at Mount Holyoke and Wheaton Colleges, as Director of Admission at Mills College (CA), interim college counselor at Rocky Hill School (RI), and has consulted broadly at a variety of colleges and independent schools. Ms. Berson, who has been a frequent speaker on college admission, is a former trustee of the College Board and currently volunteers for the World Leading Schools Theresa BLAKE Association (WLSA) where she presented sessions at their summer programs in Shanghai, China and on Jeju Island and in Seoul, Korea. She also served as a past president of the Bowdoin Alumni Council and in leadership roles for her class reunions. During vacations, she enjoys spending time with family and friends at her home on Nantucket. Title: Director of Social and Emotional Learning Institution: Appleby College Biography: Theresa Blake, M.Ed. CAPP, is the Director of Positive Education at Appleby College and is responsible for increasing faculty capacity to foster student wellbeing through theory and practice of Positive Education. Throughout her very successful teaching career, she has taught Mathematics, Sciences and French as a Second Language, and has served in multiple leadership capacities including Department Head of Languages, Director of Senior School and Director of Social and Emotional Learning (SEL). -

UK IB School Ranking (By Cohort Size)

UK IB School Ranking (by Cohort Size) Avg. Name Day/Board Boy/Girl Day £ Board £ Cohort Points Sevenoaks School Both Co-ed 24,516 37,404 205 39.6 United World College of the Atlantic Both Co-ed 168 35 St Clare's - Oxford Both Co-ed 17,967 37,052 115 35.9 King Edward's School (Boys) - Birmingham Day Boys 12,375 111 39.2 ACS Cobham International School Both Co-ed 25,680 44,360 97 29.9 Wellington College - Berkshire Both Co-ed 27,120 37,110 91 38.9 King's College - Wimbledon Day Co-ed 20,400 72 41.5 Oakham School - Rutland Both Co-ed 19,350 31,575 60 37.2 Haileybury - Hertford Both Co-ed 23,802 31,674 58 37.4 Southbank Intl School - Westminster Annexe Day Co-ed 27,660 55 35 St Leonards School - Fife Both Co-ed 13,137 32,040 54 34 King Edward's Witley Both Co-ed 19,950 29,595 51 33.4 TASIS - The American School in England Both Co-ed 22,510 39,500 50 33.9 King William's College - Castletown Both Co-ed 21,036 30,435 49 32.2 Ardingly College - Haywards Heath Both Co-ed 23,160 32,130 47 39 Marymount International School Both Girls 22,035 37,360 44 36.3 Christ's Hospital - Horsham Both Co-ed 20,490 31,500 39 36.6 ACS Hillingdon International School Day Co-ed 23,110 39 31.9 ACS Egham International School Day Co-ed 24,020 38 35.5 Felsted School - Essex Both Co-ed 22,125 32,985 37 33.9 Cheltenham Ladies' College Both Girls 26,220 38,670 36 40 Scarborough College - N. -

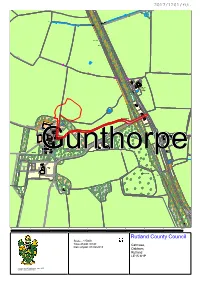

Rutland County Council Scale - 1:5000 Time of Plot: 09:49 Catmose, Date of Plot: 01/02/2018 Oakham, Rutland LE15 6HP

Issues Pond k c a r T H R m 2 .2 1 H R m 2 .2 1 y d B d r a W Farm Durham Ox Gunthorpe 98.8m MP Manton Bay Stables Pond 100.9m 98.8m AA 6600003 3 TCB LB y y galows Lay-by The Bun B B 2 2 2 y y 3 3 3 Pond a f a L L 1 1 e 1 D MP 91.75 Level Crossing 95.4m MP 91.5 SL MP 91.25 SL Level Pond Crossing Gunthorpe Bridge 900m H R m 2 .2 1 Pond Mast (Telecommunication) Issues 8 Colt Bungalow 4 4 4 5 5 5 7 6 Rutland County Council Pond Catmose, Oakham, H k T m 22 Rutland 1. LE15 6HP Sheep Dip Sheep Pens 5 n n n i i i a a a r r r D D D 6 7 k c k ra c T ra T 4 GunthorpeHall Cattle Grid Gunthorpe Cattle Grid Gunthorpe Cattle Grid Tennis CourtCourtCourt 3 Scale - 1:5000 Time of plot: 09:49 Date of plot: 01/02/2018 2 k c a r T CG CG 1 0 © Crown copyright and database rights [2013] Ordnance Survey [100018056] Application: 2017/1201/FUL ITEM 1 Proposal: New dwelling on land close to Gunthorpe Hall to facilitate enabling development for Martinsthorpe Farmhouse. Address: Gunthorpe Hall, Hall Drive, Gunthorpe, Rutland, LE15 8BE Applicant: Mr Tim Haywood Parish Gunthorpe Agent: Mr Mark Webber, Ward Martinsthorpe Nichols Brown Webber LLP Reason for presenting to Committee: Referred by Ward Member Date of Committee: 13 February 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This application for a detached single storey dwelling is intended to provide enabling development to fund the completion of restoration works at Martinsthorpe Farmhouse, an important heritage asset located on a Scheduled Monument, within the Gunthorpe Estate. -

The Clarendon Building Conservation Plan

The Clarendon Building The Clarendon Building, OxfordBuilding No. 1 144 ConservationConservation Plan, April Plan 2013 April 2013 Estates Services University of Oxford April 2013 The Clarendon Building, Oxford 2 Conservation Plan, April 2013 THE CLARENDON BUILDING, OXFORD CONSERVATION PLAN CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 7 1.1 Purpose of the Conservation Plan 7 1.2 Scope of the Conservation Plan 8 1.3 Existing Information 9 1.4 Methodology 9 1.5 Constraints 9 2 UNDERSTANDING THE SITE 13 2.1 History of the Site and University 13 2.1.1 History of the Bodleian Library complex 14 2.2 History of the Clarendon Building 16 3 SIGNIFICANCE OF THE CLARENDON BUILDING 33 3.1 Significance as part of the City Centre, Broad Street, Catte Street, and the 33 Central (City and University) Conservation Area 3.2 Significance as a constituent element of the Bodleian Library complex 35 3.3 Architectural Significance 36 3.3.1 Exterior Elevations 36 3.3.2 Internal Spaces 39 3.3.2.1 The Delegates’ Room 39 3.3.2.2 Reception 40 3.3.2.3 Admissions Office 41 The Clarendon Building, Oxford 3 Conservation Plan, April 2013 3.3.2.4 The Vice-Chancellor’s Office 41 3.3.2.5 Personnel Offices 43 3.3.2.6 Staircases 44 3.3.2.7 First-Floor Spaces 45 3.3.2.8 Second-Floor Spaces 47 3.3.2.9 Basement Spaces 48 3.4 Archaeological Significance 48 3.5 Historical and Cultural Significance 49 3.6 Significance of a functioning library administration building 49 4 VULNERABILITIES 53 4.1 Accessibility 53 4.2 Maintenance 54 4.2.1 Exterior Elevations and Setting 54 4.2.2 Interior Spaces 55 5 CONSERVATION