The Best Place to Live ….. ….For Everyone?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rutland County Council Electoral Review Submission on Warding Patterns

Rutland County Council Electoral Review Submission on Warding Patterns INTRODUCTION 1. The Council presented a Submission on Council Size to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England (LGBCE) on 11 July 2017 following approval at Full Council. On 25 July the LGBCE wrote to the Council advising that it was minded to recommend that 26 County Councillors should be elected to Rutland County Council in future in accordance with the Council’s submission. 2. The second stage of the review concerns warding arrangements. The Council size will be used to determine the average (optimum) number of Electors per councillor to be achieved across all wards of the authority. This number is reached by dividing the electorate by the number of Councillors on the authority. The LGBCE initial consultation on Warding Patterns takes place between 25 July 2017 and 2 October 2017. 3. The Constitution Review Working Group is Cross Party member group. The terms of reference for the Constitution Review Working Group (CRWG) (Agreed at Annual Council 8 May 2017) provide that the working group will review arrangements, reports and recommendations arising from Boundary and Community Governance reviews. Therefore, the CRWG undertook to develop a proposal on warding patterns which would then be presented to Full Council on 11 September 2017 for approval before submission to the LGBCE. BACKGROUND 4. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England technical guidance states that an electoral review will be required when there is a notable variance in representation across the authority. A review will be initiated when: • more than 30% of a council’s wards/divisions having an electoral imbalance of more than 10% from the average ratio for that authority; and/or • one or more wards/divisions with an electoral imbalance of more than 30%; and • the imbalance is unlikely to be corrected by foreseeable changes to the electorate within a reasonable period. -

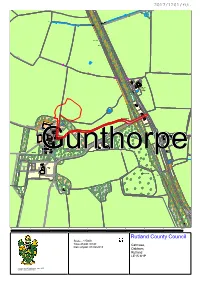

Rutland County Council Scale - 1:5000 Time of Plot: 09:49 Catmose, Date of Plot: 01/02/2018 Oakham, Rutland LE15 6HP

Issues Pond k c a r T H R m 2 .2 1 H R m 2 .2 1 y d B d r a W Farm Durham Ox Gunthorpe 98.8m MP Manton Bay Stables Pond 100.9m 98.8m AA 6600003 3 TCB LB y y galows Lay-by The Bun B B 2 2 2 y y 3 3 3 Pond a f a L L 1 1 e 1 D MP 91.75 Level Crossing 95.4m MP 91.5 SL MP 91.25 SL Level Pond Crossing Gunthorpe Bridge 900m H R m 2 .2 1 Pond Mast (Telecommunication) Issues 8 Colt Bungalow 4 4 4 5 5 5 7 6 Rutland County Council Pond Catmose, Oakham, H k T m 22 Rutland 1. LE15 6HP Sheep Dip Sheep Pens 5 n n n i i i a a a r r r D D D 6 7 k c k ra c T ra T 4 GunthorpeHall Cattle Grid Gunthorpe Cattle Grid Gunthorpe Cattle Grid Tennis CourtCourtCourt 3 Scale - 1:5000 Time of plot: 09:49 Date of plot: 01/02/2018 2 k c a r T CG CG 1 0 © Crown copyright and database rights [2013] Ordnance Survey [100018056] Application: 2017/1201/FUL ITEM 1 Proposal: New dwelling on land close to Gunthorpe Hall to facilitate enabling development for Martinsthorpe Farmhouse. Address: Gunthorpe Hall, Hall Drive, Gunthorpe, Rutland, LE15 8BE Applicant: Mr Tim Haywood Parish Gunthorpe Agent: Mr Mark Webber, Ward Martinsthorpe Nichols Brown Webber LLP Reason for presenting to Committee: Referred by Ward Member Date of Committee: 13 February 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This application for a detached single storey dwelling is intended to provide enabling development to fund the completion of restoration works at Martinsthorpe Farmhouse, an important heritage asset located on a Scheduled Monument, within the Gunthorpe Estate. -

Areas Designated As 'Rural' for Right to Buy Purposes

Areas designated as 'Rural' for right to buy purposes Region District Designated areas Date designated East Rutland the parishes of Ashwell, Ayston, Barleythorpe, Barrow, 17 March Midlands Barrowden, Beaumont Chase, Belton, Bisbrooke, Braunston, 2004 Brooke, Burley, Caldecott, Clipsham, Cottesmore, Edith SI 2004/418 Weston, Egleton, Empingham, Essendine, Exton, Glaston, Great Casterton, Greetham, Gunthorpe, Hambelton, Horn, Ketton, Langham, Leighfield, Little Casterton, Lyddington, Lyndon, Manton, Market Overton, Martinsthorpe, Morcott, Normanton, North Luffenham, Pickworth, Pilton, Preston, Ridlington, Ryhall, Seaton, South Luffenham, Stoke Dry, Stretton, Teigh, Thistleton, Thorpe by Water, Tickencote, Tinwell, Tixover, Wardley, Whissendine, Whitwell, Wing. East of North Norfolk the whole district, with the exception of the parishes of 15 February England Cromer, Fakenham, Holt, North Walsham and Sheringham 1982 SI 1982/21 East of Kings Lynn and the parishes of Anmer, Bagthorpe with Barmer, Barton 17 March England West Norfolk Bendish, Barwick, Bawsey, Bircham, Boughton, Brancaster, 2004 Burnham Market, Burnham Norton, Burnham Overy, SI 2004/418 Burnham Thorpe, Castle Acre, Castle Rising, Choseley, Clenchwarton, Congham, Crimplesham, Denver, Docking, Downham West, East Rudham, East Walton, East Winch, Emneth, Feltwell, Fincham, Flitcham cum Appleton, Fordham, Fring, Gayton, Great Massingham, Grimston, Harpley, Hilgay, Hillington, Hockwold-Cum-Wilton, Holme- Next-The-Sea, Houghton, Ingoldisthorpe, Leziate, Little Massingham, Marham, Marshland -

English Hundred-Names

l LUNDS UNIVERSITETS ARSSKRIFT. N. F. Avd. 1. Bd 30. Nr 1. ,~ ,j .11 . i ~ .l i THE jl; ENGLISH HUNDRED-NAMES BY oL 0 f S. AND ER SON , LUND PHINTED BY HAKAN DHLSSON I 934 The English Hundred-Names xvn It does not fall within the scope of the present study to enter on the details of the theories advanced; there are points that are still controversial, and some aspects of the question may repay further study. It is hoped that the etymological investigation of the hundred-names undertaken in the following pages will, Introduction. when completed, furnish a starting-point for the discussion of some of the problems connected with the origin of the hundred. 1. Scope and Aim. Terminology Discussed. The following chapters will be devoted to the discussion of some The local divisions known as hundreds though now practi aspects of the system as actually in existence, which have some cally obsolete played an important part in judicial administration bearing on the questions discussed in the etymological part, and in the Middle Ages. The hundredal system as a wbole is first to some general remarks on hundred-names and the like as shown in detail in Domesday - with the exception of some embodied in the material now collected. counties and smaller areas -- but is known to have existed about THE HUNDRED. a hundred and fifty years earlier. The hundred is mentioned in the laws of Edmund (940-6),' but no earlier evidence for its The hundred, it is generally admitted, is in theory at least a existence has been found. -

![OAKHAM. [RUTLAND.] and General Book Club and News Room, Furnished with Shoe from the Joot of One of His Horses, Which Upon His About 1,000 Volumes of Modern Works](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8157/oakham-rutland-and-general-book-club-and-news-room-furnished-with-shoe-from-the-joot-of-one-of-his-horses-which-upon-his-about-1-000-volumes-of-modern-works-1808157.webp)

OAKHAM. [RUTLAND.] and General Book Club and News Room, Furnished with Shoe from the Joot of One of His Horses, Which Upon His About 1,000 Volumes of Modern Works

DIRECTORY.] 519 OAKHAM. [RUTLAND.] and General Book Club and News Room, furnished with shoe from the Joot of one of his horses, which upon his about 1,000 volumes of modern works. refusal the bailiff of the lordship may take by force (or an The principal commercial inns are the Crown, in Hi~b equivalent sum of money for the purchase ot a horseshoe), street, the George, in the ~Iarket place, and the White to he nailed upon the Castle gate, or placed in some part of Lion, in Melton road. the building; among many of different sizes, in proportion Oakbam union comprises the following places :-Asbwel1, to the sum paid for the purchase, some of which are gilt :Barrow, Braunston, Brooke, Burley, Cold Overt on ( Leice'l and stamped with the donor's name, is one given by Queen ter), Cottesmore, Edith Weston, Egleton, Empingham, Elizabeth, a splendid one given by the late Duke of York~ Exton, Greetham, Gunthorpe, Hambleton, Horn, Knossing another by George IV., and one given by her Majesty when ton (Leicester), Langham, Leighfield Forest, Lyndon, Princess Victoria. Both courts, civil and criminal, are Manton, Market Overton, l\Iartinsthorpe, Normanton, held in the same hall, which is undivided, the Judges' seats Oakham-Deanshold with Barleythorpe, Oakham-Lords being at each end, over which are nailed some of the horse hold, Stretton, Teigh, Thistleton, Tickencote, Whissendine, shoes already mentioned. Whitwell. The Union Workhouse is a large brick building, Oakham has no incorporation, and is under the juris situated in the Ashwell road. diction of the county magistrates. -

Proactive London Partnerships Workforce Development Plans

Rutland County Council Review of Outdoor Sport and Recreation Facilities in Rutland Audit and Needs Assessment Report from Sport Structures Ltd Sport Structures Ltd, Company Number 4492940 PO Box 10710, Sutton Coldfield, B75 5YG (t): 0845 241 7195 (m): 07766 768 474 (f): 0845 241 7197 (e): [email protected] (w): www.sportstructures.com A report from Sport Structures Ltd Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 3 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 6 2 Sport and recreation context .......................................................................................... 6 Adult participation (16+) in sport and active recreation ........................................................... 8 Young people (14-25) in sport and active recreation ............................................................. 12 3 Assessment and audit approach ................................................................................... 14 4 Quantity and quality of outdoor sports facilities ............................................................. 16 Accessibility and demand from users ................................................................................... 18 5 Current Standards Summary ........................................................................................ 33 6 Conclusions and recommendations .............................................................................. -

RUTLAND. [KELLY's Oakham Has No Incorporation, and Is Under the Juris Acres; but Under the "Local Government Act, 1894,''' Diction of the County Magistrates

392 OAKHAM. RUTLAND. [KELLY'S Oakham has no incorporation, and is under the juris acres; but under the "Local Government Act, 1894,''' diction of the county magistrates. Courts-Ieet are held the parish of Deanshold with Barleythorpe was divided; annually by the lord of the manor of Lordshold, George the latter is now a separate parish, and! Deanshold and 'Henry Finch esq. M.P. of Burley-on-the-Hill, and trien Lordshold f\Jrm the parish of Oakham. The area of nially for the manor of Deanshold with Barleythorpe, of Oakham is 2,047 acres; assessable value, £12,3.t;3. The which the Dean and Chapter of Westminster are lords. popUlation of Oakham Deanshold with Barleythorpe in The chief landowners are the Earl of Gainsborough, 1891 was 1,146 and of Oakham Lordshold 2,396, including the Earl of Ancaster P. C. the Right Hon. Gerard J ames 65 officers and inmates in the workhouse. Noel P.C. the Earl of Lunsdale and George Henry Finch Gunthorpe is a township, 2 miles south; area, 476 esq. M.P. acres; assessable value, £1,328; the population in IB9I The area of Oakham Lordshold was formerly 2,010 was 24. acres; Oakham Deanshold with Barleythorpe, 1,235 Parish Clerk, George Faulks. OFFICIAL ESTABLISHMENTS, LOCAL INSTlTUTIO NS, &c. Post, M. O. &I T. 0., T. M. 0., Express Delivery, Oakham Fire Brigade, Mill street, William Ellicott, capt. ; Parcel Post,. S. B. & Annuitv & Insurance Office, William Munton, sub-capt. &; 10 men High street.--Henry George Huckman, postmaster. Oakham Institute, High street, G. H. -

Rutland Parish and Ward Boundary

SHEET 1, MAP 1 THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND ELECTORAL REVIEW OF RUTLAND Final recommendations for ward boundaries in the county of Rutland April 2018 Sheet 1 of 1 KEY TO PARISH WARDS Boundary alignment and names shown on the mapping background may not be up to date. They may differ from the latest boundary information applied as part of this review. OAKHAM CP A BARLEYTHORPE ROAD B OAKHAM NORTH EAST This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey C OAKHAM NORTH WEST on behalf of the Keeper of Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. D OAKHAM SOUTH Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and database right. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England GD100049926 2018. THISTLETON CP MARKET STRETTON OVERTON CP CP CLIPSHAM TEIGH CP CP BARROW GREETHAM WHISSENDINE CP COTTESMORE GREETHAM WHISSENDINE CP CP COTTESMORE CP ASHWELL PICKWORTH CP CP ESSENDINE CP LANGHAM RYHALL & RYHALL LANGHAM CASTERTON CP CP EXTON AND BURLEY GREAT HORN CP CP CASTERTON CP TICKENCOTE BARLEYTHORPE OAKHAM B CP NORTH EXTON BARLEYTHORPE EAST CP LITTLE A EMPINGHAM CASTERTON CP CP WHITWELL CP OAKHAM C NORTH OAKHAM WEST CP OAKHAM SOUTH D TINWELL CP EGLETON CP HAMBLETON BRAUNSTON-IN-RUTLAND CP CP NORMANTON CP GUNTHORPE BROOKE CP EDITH CP WESTON CP NORMANTON KETTON CP MARTINSTHORPE MANTON CP CP LYNDON CP LEIGHFIELD CP NORTH BRAUNSTON & LUFFENHAM CP MARTINSTHORPE PILTON CP PRESTON WING CP RIDLINGTON CP CP KETTON SOUTH LUFFENHAM CP BELTON-IN-RUTLAND MORCOTT CP AYSTON CP CP TIXOVER CP GLASTON CP WARDLEY BARROWDEN CP CP UPPINGHAM P BISBROOKE C CP CP E S A H UPPINGHAM C T N O M U A E B SEATON CP LYDDINGTON LYDDINGTON STOKE CP DRY CP THORPE BY WATER CP CALDECOTT CP KEY 00.75 1.5 3 COUNTY COUNCIL BOUNDARY PARISH BOUNDARY PROPOSED WARD BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH PARISH BOUNDARY PROPOSED WARD BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH PROPOSED PARISH WARD BOUNDARY Kilometres UPPINGHAM PROPOSED WARD NAME 1 cm = 0.3328 km TINWELL CP PARISH NAME. -

Polling Station Postal Address

Polling place addresses Parishes voting at station Ridlington Village Hall Ayston Main Street Ridlington Ridlington Oakham Rutland LE15 9AU Belton Village Hall Belton-in-Rutland Main Street Belton-in-Rutland LE15 9LB Braunston Village Hall Braunston-in-Rutland Wood Lane Brooke Braunston-in-Rutland Leighfield Oakham Rutland LE15 8QZ Preston Village Hall Preston Main Street Preston Oakham Rutland LE15 9NJ Cottesmore Village Hall The Community Centre Barrow 23 Main Street Cottesmore Cottesmore Oakham Rutland LE15 7DH Market Overton Village Hall Market Overton 52 Main Street Market Overton Oakham Rutland LE15 7PL Ashwell Village Hall Ashwell Brookdene Burley Ashwell Oakahm Rutland LE15 7LQ Egleton Village Hall Egleton Church Lane Hambleton Oakham Rutland LE15 8AD Exton Village Hall Exton & Horn The Green Whitwell Exton Oakham Rutland LE15 8AP The Olive Branch, Clipsham Clipsham Pickworth Main Street Clipsham Oakham Rutland LE15 7SH Greetham Community Centre Greetham Great Lane Greetham Oakham Rutland LE15 7NG Jackson Stops, Stretton Stretton Rookery Lane Thistleton Stretton Oakham Rutland LE15 7RA Barrowden Village Hall Barrowden Wakerley Road Barrowden Oakham Rutland LE15 8EP Ketton Library Ketton High Street Tixover Ketton Stamford Lincs PE9 3TE Tinwell Village Hall Tinwell Rear of All Saints Church Off Crown Lane Tinwell Nr Stamford Lincs PE9 3UD Langham Village Hall Langham Church Street Langham Oakham Rutland LE15 7HY St John The Baptist Church Bisbrooke Church Lane Bisbrooke Uppingham LE15 9EL Caldecott Village Hall Caldecott Church -

The Historic Country Houses of Leicestershire and Rutland

31 PART TWO The Historic Country Houses of Leicestershire And Rutland: A Gazetteer books from Belvoir Castle to Home Page Lockington Melton Hall Goadby Marwood Hall Donington Whatton House Park Buckminster Park Ragdale Staunton Prestwold Hall Old Hall Harold Hall Garendon Cotes Hall MELTON Hall Kirby MOWBRAY Coleorton LOUGHBOROUGH Edmondthorpe Bellars Hall Hall Grace Dieu Burleigh Hall Hall Stapleford Ashby Manor Quorn Hall Castle ASHBY Park Clipsham Hall -DE-LA-ZOUCH Beaumanor Park Quorn House Brooksby Hall Swithland Hall Charnwood Gaddesby Hall Rutland N. W. Leics. Ashby Folville Manor Cottesmore Hall Rothley Court Baggrave Cold Langham Exton Hall Tolethorpe Birstall Barkby Hall Overton Old Hall Exton Hall Bradgate Park Lowesby Burley-on- Old Hall the Hill Belgrave Hall Withcote OAKHAM Tickencote Hall Hall Humberstone Hall Gopsall Hambleton Old Hall Kirby Muxloe Castle Danets Scraptoft Quenby Hall Brooke Hambleton Hall Park Hall Osbaston Cavendish House Hall Ingarsby Old Launde Priory Normanton Hall Westcotes Thurnby Hall Lyndon Hall Skeffington Abbey Hall Braunstone Hall Court North Market Bosworth Hall Hall Hall Keythorpe Martinsthorpe LeicesterStoughton Hall Luffenham Hall Grange Hall Shenton Hall Ayston Hall Oadby Stretton Noseley Hall South Luffenham Hall Hinckley & Hall & Wigston Carlton Curlieu Hall Bosworth Elmesthorpe Hall Wistow Hall Nevill Blaby Holt HINCKLEY Langton Hall Hall Harborough Peatling Gumley Hall Parva Hall Papillon Country Houses Hall MARKET HARBOROUGH Mentioned in this Book Husbands N KILOMETRES Bosworth Hall Existing Country Houses 0246810 Country Houses we have lost 0246 MILES Stanford Hall 32 Leicestershire ASHBY FOLVILLE MANOR ituated eight miles north-east of SLeicester, the original manor house was built in the mid-seventeenth century on an H-plan. -

LESOPS 25 Lott Et Al

2 A Provisional Atlas of the Carabidae of Leicestershire & Rutland Derek Lott, Graham Finch & Gareth Price LESOPS 25 (2011) ISSN 0957 - 1019 A collaborative publication from The Leicestershire & Rutland Environmental Resources Centre and The Leicestershire Entomological Society 3 FOREWORD In the spring of 2009, Derek Lott, Graham Finch & Gareth Price embarked on the production of this atlas. The idea of the atlas was the brainchild of Graham Finch, who had attended a ground beetle training course and became well aware of the need for a VC55 distribution atlas. In July 2009 a very simple first draft was produced. Derek Lott and Graham Finch scrutinized the first draft. A number of important issues needed consideration, such as taxonomic changes, the classification of sites, obtaining accurate grid references and the removal of invalid species records falsely recorded in Leicestershire and Rutland. Derek Lott provided Carabidae context to some sites in the gazetteer as well as providing species context. The production of this atlas was made much easier by the life-long work of Derek Lott, who had already accumulated vast amounts of ground beetle data and local knowledge, without which this atlas would not have been possible. Special thanks go the Carabidae recorders who have sent in records. We have endeavoured to reference and acknowledge the people and sources that have helped in the production of this atlas but often with natural history publications there are too many people to thank over a very long period of time. Our apologies go to the people or sources that have been inadvertently omitted. The gazetteer obtained information from a number of sources, in particular the Flora of Leicestershire (Primavesi & Evans, 1988) and the Flora of Rutland (Messenger, 1971). -

The Oakham Survey Research Group

THE OAKHAMSURVEY OF 1305 A Translation with Commentaries by The Oakham Survey Research Group Rutland Record Society 1988 1989 Published by Rutland Record Society, Rutland County Museum, Oakham, LE15 6HW © Rutland Record Society and Oakham Survey Research Group ISBN 0-907464-07-6 Membership oftbe Oakham Survey Research Group A. D. Adams; O. R. Adams; G. A. Chinnery (co-ordinator); E. B. Dean; B. T. Finch; G. S. Finch; M. N. Gavins; P. N. Lane; D. A. Parkin; M. F. Parkin. Printed in Great Britain by Woolnough Bookbinding Ltd., Church Street, Irthlingborough, Northants, England. CONTENTS Page The origin and progress of the project 5 A description of the survey 7 Its dating and purpose 9 Working methods and conventions 10 Contents list of the survey 11 Translation of the survey 13 The property roll, inconsistencies and duplications 37 Notes on the knight's fee and holdings in Rutland 39 The feudal services 41 Names, bye names and trades 42 The placenames in the survey 43 Glossary 46 Bibliography 48 Index of places 49 Index of names 52 An Extract from the Oakham Survey, Line 154, marked by an asterisk above, reads as follows: J ohes' de Braunderston tenet j mess' & viij virg' t're et r' p' an' ixs ad iiij t'ios Et fac' sect' cur' Translation John de Braundeston holds one messuage and eight uirgates of land and pays yearly 9s at the four terms and does suit of court The Origin and Progress of the Project In 1984 the Oakham branch of the Worker's Educa heading 'Okeham' at the beginning it had no titling tional Association responded to the requests of a or introduction.