Rutland Record No. 14 1994

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

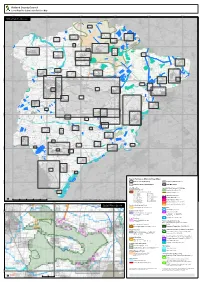

Rutland Main Map A0 Portrait

Rutland County Council Local Plan Pre-Submission Policies Map 480000 485000 490000 495000 500000 505000 Rutland County - Main map Thistleton Inset 53 Stretton (west) Clipsham Inset 51 Market Overton Inset 13 Inset 35 Teigh Inset 52 Stretton Inset 50 Barrow Greetham Inset 4 Inset 25 Cottesmore (north) 315000 Whissendine Inset 15 Inset 61 Greetham (east) Inset 26 Ashwell Cottesmore Inset 1 Inset 14 Pickworth Inset 40 Essendine Inset 20 Cottesmore (south) Inset 16 Ashwell (south) Langham Inset 2 Ryhall Exton Inset 30 Inset 45 Burley Inset 21 Inset 11 Oakham & Barleythorpe Belmesthorpe Inset 38 Little Casterton Inset 6 Rutland Water Inset 31 Inset 44 310000 Tickencote Great Inset 55 Casterton Oakham town centre & Toll Bar Inset 39 Empingham Inset 24 Whitwell Stamford North (Quarry Farm) Inset 19 Inset 62 Inset 48 Egleton Hambleton Ketton Inset 18 Inset 27 Inset 28 Braunston-in-Rutland Inset 9 Tinwell Inset 56 Brooke Inset 10 Edith Weston Inset 17 Ketton (central) Inset 29 305000 Manton Inset 34 Lyndon Inset 33 St. George's Garden Community Inset 64 North Luffenham Wing Inset 37 Inset 63 Pilton Ridlington Preston Inset 41 Inset 43 Inset 42 South Luffenham Inset 47 Belton-in-Rutland Inset 7 Ayston Inset 3 Morcott Wardley Uppingham Glaston Inset 36 Tixover Inset 60 Inset 58 Inset 23 Barrowden Inset 57 Inset 5 Uppingham town centre Inset 59 300000 Bisbrooke Inset 8 Seaton Inset 46 Eyebrook Reservoir Inset 22 Lyddington Inset 32 Stoke Dry Inset 49 Thorpe by Water Inset 54 Key to Policies on Main and Inset Maps Rutland County Boundary Adjoining -

BRONZE AGE SETTLEMENT at RIDLINGTON, RUTLAND Matthew Beamish

01 Ridlington - Beamish 30/9/05 3:19 pm Page 1 BRONZE AGE SETTLEMENT AT RIDLINGTON, RUTLAND Matthew Beamish with contributions from Lynden Cooper, Alan Hogg, Patrick Marsden, and Angela Monckton A post-ring roundhouse and adjacent structure were recorded by University of Leicester Archaeological Services, during archaeological recording preceding laying of the Wing to Whatborough Hill trunk main in 1996 by Anglian Water plc. The form of the roundhouse together with the radiocarbon dating of charred grains and finds of pottery and flint indicate that the remains stemmed from occupation toward the end of the second millennium B.C. The distribution of charred cereal remains within the postholes indicates that grain including barley was processed and stored on site. A pit containing a small quantity of Beaker style pottery was also recorded to the east, whilst a palaeolith was recovered from the infill of a cryogenic fissure. The remains were discovered on the northern edge of a flat plateau of Northamptonshire Sand Ironstone at between 176 and 177m ODSK832023). The plateau forms a widening of a west–east ridge, a natural route way, above northern slopes down into the Chater Valley, and abrupt escarpments above the parishes of Ayston and Belton to the south (illus. 2). Near to the site, springs issue from just below the 160m and 130m contours to the north and south east respectively and ponds exist to the east corresponding with a boulder clay cap. The area was targeted for investigation as it lay on the northern fringe of a substantial Mesolithic/Early Neolithic flint scatter (LE5661, 5662, 5663) (illus. -

The Best Place to Live ….. ….For Everyone?

Rutland - the best place to live ….. ….for everyone? A Report on Poverty in Rutland 2016 Barbara Coulson BA., MA Cantab., MA Nottingham CONTENTS Executive Summary ........................................................................................... 2 Citizens Advice Rutland .................................................................................... 5 Why a Rutland rural poverty report? ........................................................... 6 IntroductiIntroductionononon .....................................................................................................6 Defining Poverty ..............................................................................................7 Rutland and Rural Poverty ..............................................................................9 Measuring PoPovertyverty and Deprivation in Rutland .......................................... 11 The Determinants of Poverty - Income Deprivation .............................. 13 The Determinants of Poverty - High Costs ................................................ 18 Housing and Associated Costs .....................................................................18 Fuel Costs and Fuel Poverty ..........................................................................24 Food Poverty .................................................................................................29 Transport and Poverty ..................................................................................32 Poverty as it affects people .......................................................................... -

Rutland County Council Electoral Review Submission on Warding Patterns

Rutland County Council Electoral Review Submission on Warding Patterns INTRODUCTION 1. The Council presented a Submission on Council Size to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England (LGBCE) on 11 July 2017 following approval at Full Council. On 25 July the LGBCE wrote to the Council advising that it was minded to recommend that 26 County Councillors should be elected to Rutland County Council in future in accordance with the Council’s submission. 2. The second stage of the review concerns warding arrangements. The Council size will be used to determine the average (optimum) number of Electors per councillor to be achieved across all wards of the authority. This number is reached by dividing the electorate by the number of Councillors on the authority. The LGBCE initial consultation on Warding Patterns takes place between 25 July 2017 and 2 October 2017. 3. The Constitution Review Working Group is Cross Party member group. The terms of reference for the Constitution Review Working Group (CRWG) (Agreed at Annual Council 8 May 2017) provide that the working group will review arrangements, reports and recommendations arising from Boundary and Community Governance reviews. Therefore, the CRWG undertook to develop a proposal on warding patterns which would then be presented to Full Council on 11 September 2017 for approval before submission to the LGBCE. BACKGROUND 4. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England technical guidance states that an electoral review will be required when there is a notable variance in representation across the authority. A review will be initiated when: • more than 30% of a council’s wards/divisions having an electoral imbalance of more than 10% from the average ratio for that authority; and/or • one or more wards/divisions with an electoral imbalance of more than 30%; and • the imbalance is unlikely to be corrected by foreseeable changes to the electorate within a reasonable period. -

Designated Rural Areas and Designated Regions) (England) Order 2004

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2004 No. 418 HOUSING, ENGLAND The Housing (Right to Buy) (Designated Rural Areas and Designated Regions) (England) Order 2004 Made - - - - 20th February 2004 Laid before Parliament 25th February 2004 Coming into force - - 17th March 2004 The First Secretary of State, in exercise of the powers conferred upon him by sections 157(1)(c) and 3(a) of the Housing Act 1985(1) hereby makes the following Order: Citation, commencement and interpretation 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the Housing (Right to Buy) (Designated Rural Areas and Designated Regions) (England) Order 2004 and shall come into force on 17th March 2004. (2) In this Order “the Act” means the Housing Act 1985. Designated rural areas 2. The areas specified in the Schedule are designated as rural areas for the purposes of section 157 of the Act. Designated regions 3.—(1) In relation to a dwelling-house which is situated in a rural area designated by article 2 and listed in Part 1 of the Schedule, the designated region for the purposes of section 157(3) of the Act shall be the district of Forest of Dean. (2) In relation to a dwelling-house which is situated in a rural area designated by article 2 and listed in Part 2 of the Schedule, the designated region for the purposes of section 157(3) of the Act shall be the district of Rochford. (1) 1985 c. -

Royal Forest Trail

Once there was a large forest on the borders of Rutland called the Royal Forest of Leighfield. Now only traces remain, like Prior’s Coppice, near Leighfield Lodge. The plentiful hedgerows and small fields in the area also give hints about the past vegetation cover. Villages, like Belton and Braunston, once deeply situated in the forest, are square shaped. This is considered to be due to their origin as enclosures within the forest where the first houses surrounded an open space into which animals could be driven for their protection and greater security - rather like the covered wagon circle in the American West. This eventually produced a ‘hollow-centred’ village later filled in by buildings. In Braunston the process of filling in the centre had been going on for many centuries. Ridlington betrays its forest proximity by its ‘dead-end’ road, continued only by farm tracks today. The forest blocked entry in this direction. Indeed, if you look at the 2 ½ inch O.S map you will notice that there are no through roads between Belton and Braunston due to the forest acting as a physical administrative barrier. To find out more about this area, follow this trail… You can start in Oakham, going west out of town on the Cold Overton Road, then 2nd left onto West Road towards Braunston. Going up the hill to Braunston. In Braunston, walk around to see the old buildings such as Cheseldyn Farm and Quaintree Hall; go down to the charming little bridge over the River Gwash (the stream flowing into Rutland Water). -

Sources of Langham Local History Information 11Th C > 19Th C

Langham in Rutland Local History Sources of Information Compiled by Nigel Webb Revision 2 - 11 November 2020 Contents Introduction 11th to 13th century 14th century 15th century 16th century 17th century 18th century 19th century Please select one of the above Introduction The intention of this list of possible sources is to provide starting points for researchers. Do not be put off by the length of the list: you will probably need only a fraction of it. For the primary sources – original documents or transcriptions of these – efforts have been made to include everything which might be productive. If you know of or find further such sources which should be on this list, please tell the Langham Village History Group archivist so that they can be added. If you find a source that we have given particularly productive, please tell us what needs it has satisfied; if you are convinced that it is a waste of time, please tell us this too! For the secondary sources – books, journals and internet sites – we have tried to include just enough useful ones, whatever aspect of Langham history that you might wish to investigate. However, we realise that there is then a danger of the list looking discouragingly long. Probably you will want to look at only a fraction of these. For many of the books, just a single chapter or a small section found from the index, or even a sentence, here and there, useful for quotation, is all that you may want. But, again, if you find or know of further especially useful sources, please tell us. -

Introduction 1

Notes Introduction 1. Thomas Ertman, Birth of the Leviathon. Building States and Regimes in Medieval and Early Modern Europe (Cambridge, 1997). The seventh and last volume to appear in the European Science Foundation Series was War and Competition between States, ed. Philippe Contamine (Ox- ford, 2000). It lists earlier works in the series. 2. Resistance, Representation, and Community, ed. Peter Blickle (Oxford, 1997). 3. Discontent with taxation is well illustrated in J. R. Maddicott, The En- glish Peasantry and the Demands of the Crown. Past & Present Supple- ment, no. 1 (Oxford, 1975). 4. Kathryn L. Reyerson, “Commerce and Communications” in The New Cambridge Medieval History, ed. David Abulafia (Cambridge, 1999), vol. 5, c.1198-c.1300, pp. 50–70; Peter Spufford, Power and Profit. The Merchant in Medieval Europe (London, 2002); John Langdon and James Masschaele, “Commercial Activity and Population Growth in Medieval England,” Past & Present 190 (2006): 35–81; James Mass- chaele, “Economic Takeoff and the Rise of Markets,” in Blackwell Com- panion to the Middle Ages, ed. Edward D. English and Carol L. Lansing (Oxford, forthcoming 2008). 5. Michael Clanchy, From Memory to Written Record: England 1066–1307, 2nd ed. (Oxford, 1993); Pragmatic Literacy East and West, 1200–1330, ed. Richard Britnell (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 1997). 6. James Scott, Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance (New Haven, 1987). 7. Susan Reynolds, Kingdoms and Communities in Western Europe, 900–1300 (Oxford, 1984); Alan Harding, Medieval Law and the Foun- dations of the State (Oxford, 2002). 8. Alfred B.White, Self-Government at the King’s Command (Minneapolis, 1933). -

LAA 2014 Final

Local Aggregates Assessment (Jan – Dec 2015) November 2016 Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 Data limitations .................................................................................................................. 2 2. Aggregate supply and demand ................................................................................... 3 Geology ............................................................................................................................. 3 Limestone .......................................................................................................................... 4 Rutland sales ..................................................................................................................... 7 Sand and gravel ................................................................................................................. 9 Ironstone .......................................................................................................................... 10 Clay ................................................................................................................................. 10 Recycled and secondary aggregates ............................................................................... 10 3. Future aggregate supply ........................................................................................... 13 Aggregate provision ........................................................................................................ -

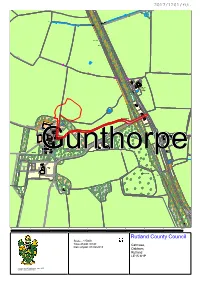

Rutland County Council Scale - 1:5000 Time of Plot: 09:49 Catmose, Date of Plot: 01/02/2018 Oakham, Rutland LE15 6HP

Issues Pond k c a r T H R m 2 .2 1 H R m 2 .2 1 y d B d r a W Farm Durham Ox Gunthorpe 98.8m MP Manton Bay Stables Pond 100.9m 98.8m AA 6600003 3 TCB LB y y galows Lay-by The Bun B B 2 2 2 y y 3 3 3 Pond a f a L L 1 1 e 1 D MP 91.75 Level Crossing 95.4m MP 91.5 SL MP 91.25 SL Level Pond Crossing Gunthorpe Bridge 900m H R m 2 .2 1 Pond Mast (Telecommunication) Issues 8 Colt Bungalow 4 4 4 5 5 5 7 6 Rutland County Council Pond Catmose, Oakham, H k T m 22 Rutland 1. LE15 6HP Sheep Dip Sheep Pens 5 n n n i i i a a a r r r D D D 6 7 k c k ra c T ra T 4 GunthorpeHall Cattle Grid Gunthorpe Cattle Grid Gunthorpe Cattle Grid Tennis CourtCourtCourt 3 Scale - 1:5000 Time of plot: 09:49 Date of plot: 01/02/2018 2 k c a r T CG CG 1 0 © Crown copyright and database rights [2013] Ordnance Survey [100018056] Application: 2017/1201/FUL ITEM 1 Proposal: New dwelling on land close to Gunthorpe Hall to facilitate enabling development for Martinsthorpe Farmhouse. Address: Gunthorpe Hall, Hall Drive, Gunthorpe, Rutland, LE15 8BE Applicant: Mr Tim Haywood Parish Gunthorpe Agent: Mr Mark Webber, Ward Martinsthorpe Nichols Brown Webber LLP Reason for presenting to Committee: Referred by Ward Member Date of Committee: 13 February 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This application for a detached single storey dwelling is intended to provide enabling development to fund the completion of restoration works at Martinsthorpe Farmhouse, an important heritage asset located on a Scheduled Monument, within the Gunthorpe Estate. -

Local Plan Review Issues and Options Consultation Document

1 Rutland Local Plan Review Issues and Options Consultation Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 3 How can sites for new housing and other development be put forward? ........................... 6 Neighbourhood Plans............................................................................................................ 8 What role should the Local Plan take in coordinating neighbourhood plans? .................... 8 The spatial portrait, vision and objectives .............................................................................. 9 Are changes to the spatial portrait, vision or objectives needed? ...................................... 9 The spatial strategy ............................................................................................................. 10 Are changes to the settlement hierarchy needed? ........................................................... 10 How much new housing will be needed? ......................................................................... 16 Will sites for employment, retail or other uses need to be allocated?............................... 18 What type of new housing is going to be needed? .......................................................... 19 How will new development be apportioned between the towns and villages? .................. 21 How will new growth be apportioned between Oakham and Uppingham? ....................... 23 Site allocations ................................................................................................................... -

Areas Designated As 'Rural' for Right to Buy Purposes

Areas designated as 'Rural' for right to buy purposes Region District Designated areas Date designated East Rutland the parishes of Ashwell, Ayston, Barleythorpe, Barrow, 17 March Midlands Barrowden, Beaumont Chase, Belton, Bisbrooke, Braunston, 2004 Brooke, Burley, Caldecott, Clipsham, Cottesmore, Edith SI 2004/418 Weston, Egleton, Empingham, Essendine, Exton, Glaston, Great Casterton, Greetham, Gunthorpe, Hambelton, Horn, Ketton, Langham, Leighfield, Little Casterton, Lyddington, Lyndon, Manton, Market Overton, Martinsthorpe, Morcott, Normanton, North Luffenham, Pickworth, Pilton, Preston, Ridlington, Ryhall, Seaton, South Luffenham, Stoke Dry, Stretton, Teigh, Thistleton, Thorpe by Water, Tickencote, Tinwell, Tixover, Wardley, Whissendine, Whitwell, Wing. East of North Norfolk the whole district, with the exception of the parishes of 15 February England Cromer, Fakenham, Holt, North Walsham and Sheringham 1982 SI 1982/21 East of Kings Lynn and the parishes of Anmer, Bagthorpe with Barmer, Barton 17 March England West Norfolk Bendish, Barwick, Bawsey, Bircham, Boughton, Brancaster, 2004 Burnham Market, Burnham Norton, Burnham Overy, SI 2004/418 Burnham Thorpe, Castle Acre, Castle Rising, Choseley, Clenchwarton, Congham, Crimplesham, Denver, Docking, Downham West, East Rudham, East Walton, East Winch, Emneth, Feltwell, Fincham, Flitcham cum Appleton, Fordham, Fring, Gayton, Great Massingham, Grimston, Harpley, Hilgay, Hillington, Hockwold-Cum-Wilton, Holme- Next-The-Sea, Houghton, Ingoldisthorpe, Leziate, Little Massingham, Marham, Marshland