Chapter One: Introduction: Definition of Myth and Myth in Indian Fiction In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

Samudra-Manthan

SAMUDRA-MANTHAN Swami Nirvikarananda Introduction The ancient story of Samudra-manthan of the Hindu tradition has got a deep spiritual meaning for all humanity, especially in this modern age. During the past four hundred years, man has been doing, what the myth refers to us as, samudra-manthan, ‘churning the ocean’, through his scientific discoveries, technological inventions, industrial developments, and socio-economic programmes. Man ‘churns’ the ‘oceans’ of his life and experience, churns the whole nature, to obtain the ‘nectar’ of happy, joyous, and fulfilled life—a churning that has become intensified in the modern period. The Ancient Myth and the Modern Reality The vigorous churning of the ocean by the gods and the demons produced both poison and nectar, along with many other good and useful and attractive things in between, says the myth. The modern churning also, similarly, has produced beneficent and harmful things in abundance. When the beneficent things emerge, men rush towards them to possess them and to enjoy them. When harmful things emerge, all run away in fear and consternation. The gods and demons in the myth also behaved similarly. Among the beneficent and attractive things that came out, according to the myth, are Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and welfare, and Dhanvantari, the god of health and longevity, bringing with him the pot of nectar capable of conferring immortality on the churning participants. That led to competition, strife, and bitter war between the two groups, in the struggle to obtain the nectar for oneself and deprive the other group of it. The harmful thing that came out was the terrible poison called halāhala or kālakūta. -

Wish You All a Very Happy Diwali Page 2

Hindu Samaj Temple of Minnesota Oct, 2012 President’s Note Dear Community Members, Namaste! Deepavali Greetings to You and Your Family! I am very happy to see that Samarpan, the Hindu Samaj Temple and Cultural Center’s Newslet- ter/magazine is being revived. Samarpan will help facilitate the accomplishment of the Temple and Cultural Center’s stated threefold goals: a) To enhance knowledge of Hindu Religion and Indian Cul- ture. b) To make the practice of Hindu Religion and Culture accessible to all in the community. c) To advance the appreciation of Indian culture in the larger community. We thank the team for taking up this important initiative and wish them and the magazine the Very Best! The coming year promises to be an exciting one for the Temple. We look forward to greater and expand- ed religious and cultural activities and most importantly, the prospect of buying land for building a for- mal Hindu Temple! Yes, we are very close to signing a purchase agreement with Bank to purchase ~8 acres of land in NE Rochester! It has required time, patience and perseverance, but we strongly believe it will be well worth the wait. As soon as we have the made the purchase we will call a meeting of the community to discuss our vision for future and how we can collectively get there. We would greatly welcome your feedback. So stay tuned… Best wishes for the festive season! Sincerely, Suresh Chari President, Hindu Samaj Temple Wish you all a Very Happy Diwali Page 2 Editor’s Note By Rajani Sohni Welcome back to all our readers! After a long hiatus, we are bringing Samarpan back to life. -

Mahabharata Tatparnirnaya

Mahabharatha Tatparya Nirnaya Chapter XIX The episodes of Lakshagriha, Bhimasena's marriage with Hidimba, Killing Bakasura, Draupadi svayamwara, Pandavas settling down in Indraprastha are described in this chapter. The details of these episodes are well-known. Therefore the special points of religious and moral conduct highlights in Tatparya Nirnaya and its commentaries will be briefly stated here. Kanika's wrong advice to Duryodhana This chapter starts with instructions of Kanika an expert in the evil policies of politics to Duryodhana. This Kanika was also known as Kalinga. Probably he hailed from Kalinga region. He was a person if Bharadvaja gotra and an adviser to Shatrujna the king of Sauvira. He told Duryodhana that when the close relatives like brothers, parents, teachers, and friends are our enemies, we should talk sweet outwardly and plan for destroying them. Heretics, robbers, theives and poor persons should be employed to kill them by poison. Outwardly we should pretend to be religiously.Rituals, sacrifices etc should be performed. Taking people into confidence by these means we should hit our enemy when the time is ripe. In this way Kanika secretly advised Duryodhana to plan against Pandavas. Duryodhana approached his father Dhritarashtra and appealed to him to send out Pandavas to some other place. Initially Dhritarashtra said Pandavas are also my sons, they are well behaved, brave, they will add to the wealth and the reputation of our kingdom, and therefore, it is not proper to send them out. However, Duryodhana insisted that they should be sent out. He said he has mastered one hundred and thirty powerful hymns that will protect him from the enemies. -

03 Reviews of Literature.Pdf

REVIEWS OF THE RELATED LITERATURE While reading thesis, books and journals I have got reviews from the other scholars who have worked on major Indian literature. Malik,(2013) from the centre for comparative study of Indian Languages and cultural, Aligahrdh Muslim University has presented a paper in Asian journal of social science and humanities under the title “Cultural and Linguistic issues in Translation of fiction with special reference to Amin Kamil‟s short story The Cock Fight. This paper is based on the translation of a collection of stories “ Kashmiri Short stories.” He has chosen story The Cock fight .It is translated by M.S. Beigh. He wants to focus that translation process of the linguistic and cultural issues encountered in the original and how they were resolved in translation. Tamilselvi,(2013) Assistant professor of English ,at SFR college at Tamilnadu has written a paper in Criterion journal under the title; “ Depiction of Parsi World –view in selected Short Stories of Rohinton Mistry‟s Tales from Firozha Baag”(2013) The paper focuses on Rohan Mistry‟s experiences as a minority status. She illustrates how Mistry has depicted the life of Parsis their customs in the stories. He also records Parsi‟s social circumstances ,sense of isolation and ruthlessness ,tie them to gather and make them forge a bond of understanding as they struggle to survive. Roy,(2012) assistant professor in Karim city College, Jameshedpur has written an article in Criterion Journal under the title Re- Inscribing the mother within motherhood : A Feminist Reading of Shauna Singh Baldwin‟s Short Story Naina The paper examines to look at Naina‟s experience of motherhood as a deconstruction of the patriarchal maternity narrative and attempt to reclaim the subject-position of the mother through Dependence/Independence of motherhood from the father paternal authority on the material subject Mother-daughter relationship and linking Gestation and creativity . -

Temple and Songs Links

TEMPLE AND SONGS LINKS This is a modest attempt to explore the famous temples of India and post songs composed in praise of each of them culled out form many sites . I've never come across a site that provides such information. Of course, there are close to 30000 temples in Tamil Nadu alone and it would take a long time to even cover 1% of these but it never hurts to start! I hope this information will be useful to carnatic music lovers of our group . I for one is a buffllo when it comes to carantic music ragas . but documented information is power hence this documentation . Meenakshi Sundareshwarar Temple (Madurai) The Meenakshi Amman Temple at Madurai is one of the most famous temples in South India as this is where, according to Hindu legends, Lord Shiva appeared on Earth in the form of Sundareshwarar to marry Pandya King Malayadwaja Pandya's daughter, Meenakshi (believed to be an incarnation of Hindu Goddess Parvati). A detailed article on this divine marriage can be found here http://templenet.com/Tamilnadu/Madurai/legend3.html. As mentioned in the article, the legend of Meenakshi Kalyanam brings together four of the six main streams in popular Hinduism - Shaiva, Shaktha, Vaishnava, and Skanda faiths. Before describing this beautiful temple in detail, I' d like to share a recording of a wonderful song composed by Sri Papanasam Sivan, in praise of the Goddess Meenakshi at Madurai. The song is 'Devi Neeye', rendered by the late M.S.Subbulakshmi. According to legend, Lord Sundareshwara (as Sundara Pandya) and his consort Goddess Meenakshi ruled over Madurai for a long period of time. -

A Study of Devdutt Pattanaik's the Pregnant King

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (JHSS) ISSN: 2279-0837, ISBN: 2279-0845. Volume 4, Issue 3 (Nov. - Dec. 2012), PP 22-25 www.Iosrjournals.Org Uncovering the Sexual/Gender Politics: a Study of Devdutt Pattanaik’s the Pregnant King Somrita Dey Vivekananda Mahavidyalaya, Burdwan, India Abstract: The concerned paper is an exploration of society’s repeated attempts to uphold the male/female and masculine/feminine binary by silencing those human conducts that deviate from the path of supposed normalcy, as presented in Devdutt Pattanaik’s novel. The affirmation of the non-existence of all forms of marginal sexualities, and those human tendencies that violate the gender stereotypes, is imperative to the preservation of the binary structure and hence their suppression. The paper attempts to delineate how even the slightest violation of sexual and gender norms are denied expression and ruthlessly silenced. Keywords: Gender roles, Marginal sexuality, Society, Suppression. I. Introduction …thou shalt not speak, thou shalt not show thyself… ultimately thou shalt not exist, except in darkness and secrecy…do not appear if you don’t want to disappear.[1] Society since time immemorial has endeavoured to suppress voices that refuse to subscribe to the existing social codes of conduct. Human beings perceive the world in dyads of binary opposition –good/bad, white/black, man/woman so on and so forth, and whatever fails to conform to this binary structure is relegated to the margins and in due course dexterously obliterated. Devdutt Pattanaik’s The Pregnant King is an exploration of society’s recurrent efforts to silence all human behaviours that register either an implicit or explicit violation of this structure vis-à-vis the binary of male/female and of masculinity/femininity, by default. -

Recruitment.Guru in Case of Any Guidance/Information/Clarification Regarding Their Applications, Candidature Etc

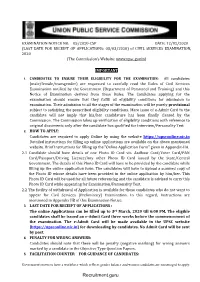

EXAMINATION NOTICE NO. 05/2020-CSP DATE: 12/02/2020 (LAST DATE FOR RECEIPT OF APPLICATIONS: 03/03/2020) of CIVIL SERVICES EXAMINATION, 2020 (The Commission’s Website: www.upsc.gov.in) IMPORTANT 1. CANDIDATES TO ENSURE THEIR ELIGIBILITY FOR THE EXAMINATION: All candidates (male/female/transgender) are requested to carefully read the Rules of Civil Services Examination notified by the Government (Department of Personnel and Training) and this Notice of Examination derived from these Rules. The Candidates applying for the examination should ensure that they fulfill all eligibility conditions for admission to examination. Their admission to all the stages of the examination will be purely provisional subject to satisfying the prescribed eligibility conditions. Mere issue of e-Admit Card to the candidate will not imply that his/her candidature has been finally cleared by the Commission. The Commission takes up verification of eligibility conditions with reference to original documents only after the candidate has qualified for Interview/Personality Test. 2. HOW TO APPLY: Candidates are required to apply Online by using the website https://upsconline.nic.in Detailed instructions for filling up online applications are available on the above mentioned website. Brief Instructions for filling up the "Online Application Form" given in Appendix-IIA. 2.1 Candidate should have details of one Photo ID Card viz. Aadhaar Card/Voter Card/PAN Card/Passport/Driving Licence/Any other Photo ID Card issued by the State/Central Government. The details of this Photo ID Card will have to be provided by the candidate while filling up the online application form. The candidates will have to upload a scanned copy of the Photo ID whose details have been provided in the online application by him/her. -

Rearticulations of Enmity and Belonging in Postwar Sri Lanka

BUDDHIST NATIONALISM AND CHRISTIAN EVANGELISM: REARTICULATIONS OF ENMITY AND BELONGING IN POSTWAR SRI LANKA by Neena Mahadev A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland October, 2013 © 2013 Neena Mahadev All Rights Reserved Abstract: Based on two years of fieldwork in Sri Lanka, this dissertation systematically examines the mutual skepticism that Buddhist nationalists and Christian evangelists express towards one another in the context of disputes over religious conversion. Focusing on the period from the mid-1990s until present, this ethnography elucidates the shifting politics of nationalist perception in Sri Lanka, and illustrates how Sinhala Buddhist populists have increasingly come to view conversion to Christianity as generating anti-national and anti-Buddhist subjects within the Sri Lankan citizenry. The author shows how the shift in the politics of identitarian perception has been contingent upon several critical events over the last decade: First, the death of a Buddhist monk, which Sinhala Buddhist populists have widely attributed to a broader Christian conspiracy to destroy Buddhism. Second, following the 2004 tsunami, massive influxes of humanitarian aid—most of which was secular, but some of which was connected to opportunistic efforts to evangelize—unsettled the lines between the interested religious charity and the disinterested secular giving. Third, the closure of 25 years of a brutal war between the Sri Lankan government forces and the ethnic minority insurgent group, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), has opened up a slew of humanitarian criticism from the international community, which Sinhala Buddhist populist activists surmise to be a product of Western, Christian, neo-colonial influences. -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

Retellings of the Indian Epics

(RJELAL) Research Journal of English Language and Literature Vol.4.Issue 2.2016 A Peer Reviewed (Refereed) International Journal (Apr-Jun) http://www.rjelal.com; Email:[email protected] REVIEW ARTICLE THE FASCINATING WORLD OF RETELLINGS: RETELLINGS OF THE INDIAN EPICS PRIYANKA P.S. KUMAR M A English Literature USHAMALARY, THEKKUMKARA, NEDUMANGAD P O. THIRUVANANTHAPURAM, KERALA ABSTRACT The Indian epics provide a good number of materials for the modern day writers to interpret and re-create. The web of retellings makes it possible that each creative writer can claim a new version of his own. The Indian epics are retold by many writers. These include indigenous as well as foreign versions. Many of these re- workings aim to bring out the ideologies of the age. These retellings were influenced by the predominant social, political and cultural tendencies. They helped in PRIYANKA P.S. surveying the epic from different angles and helped in reviving the various KUMAR characters that were thrown to the margins by main stream literature. Thus, we can say that the exploration through the various retellings of the epics is at the same time interesting, inspirational and thought provoking. Key Words: Retellings, Indian epics, Narrative tradition ©KY PUBLICATIONS Is there a single author or compiler? ….. epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata provide Is there a single text? ( www.mahabharatha many stories and sub stories which form the richest resources.org) treasure house of Indian narratology. Apart from Human beings always live in a social group providing infinite number of tales, they provide an interacting with each other, sharing their thoughts umbrella concept of fictional resources that appeal feelings and emotions.