14 the Tinggians of Abra Cellophil a Situation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NDCC Update Sitrep No. 19 Re TY Pepeng As of 10 Oct 12:00NN

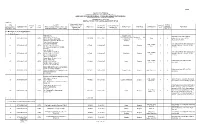

2 Pinili 1 139 695 Ilocos Sur 2 16 65 1 Marcos 2 16 65 La Union 35 1,902 9,164 1 Aringay 7 570 3,276 2 Bagullin 1 400 2,000 3 Bangar 3 226 1,249 4 Bauang 10 481 1,630 5 Caba 2 55 193 6 Luna 1 4 20 7 Pugo 3 49 212 8 Rosario 2 30 189 San 9 Fernand 2 10 43 o City San 10 1 14 48 Gabriel 11 San Juan 1 19 111 12 Sudipen 1 43 187 13 Tubao 1 1 6 Pangasinan 12 835 3,439 1 Asingan 5 114 458 2 Dagupan 1 96 356 3 Rosales 2 125 625 4 Tayug 4 500 2,000 • The figures above may continue to go up as reports are still coming from Regions I, II and III • There are now 299 reported casualties (Tab A) with the following breakdown: 184 Dead – 6 in Pangasinan, 1 in Ilocos Sur (drowned), 1 in Ilocos Norte (hypothermia), 34 in La Union, 133 in Benguet (landslide, suffocated secondary to encavement), 2 in Ifugao (landslide), 2 in Nueva Ecija, 1 in Quezon Province, and 4 in Camarines Sur 75 Injured - 1 in Kalinga, 73 in Benguet, and 1 in Ilocos Norte 40 Missing - 34 in Benguet, 1 in Ilocos Norte, and 5 in Pangasinan • A total of 20,263 houses were damaged with 1,794 totally and 18,469 partially damaged (Tab B) • There were reports of power outages/interruptions in Regions I, II, III and CAR. Government offices in Region I continue to be operational using generator sets. -

Income Classification Per DOF Order No. 23-08, Dated July 29, 2008 MUNICIPALITIES Classification NCR 1

Income Classification Per DOF Order No. 23-08, dated July 29, 2008 MUNICIPALITIES Classification NCR 1. Pateros 1st CAR ABRA 1 Baay-Licuan 5th 2 Bangued 1st 3 Boliney 5th 4 Bucay 5th 5 Bucloc 6th 6 Daguioman 5th 7 Danglas 5th 8 Dolores 5th 9 La Paz 5th 10 Lacub 5th 11 Lagangilang 5th 12 Lagayan 5th 13 Langiden 5th 14 Luba 5th 15 Malibcong 5th 16 Manabo 5th 17 Penarrubia 6th 18 Pidigan 5th 19 Pilar 5th 20 Sallapadan 5th 21 San Isidro 5th 22 San Juan 5th 23 San Quintin 5th 24 Tayum 5th 25 Tineg 2nd 26 Tubo 4th 27 Villaviciosa 5th APAYAO 1 Calanasan 1st 2 Conner 2nd 3 Flora 3rd 4 Kabugao 1st 5 Luna 2nd 6 Pudtol 4th 7 Sta. Marcela 4th BENGUET 1. Atok 4th 2. Bakun 3rd 3. Bokod 4th 4. Buguias 3rd 5. Itogon 1st 6. Kabayan 4th 7. Kapangan 4th 8. Kibungan 4th 9. La Trinidad 1st 10. Mankayan 1st 11. Sablan 5th 12. Tuba 1st blgf/ltod/updated 1 of 30 updated 4-27-16 Income Classification Per DOF Order No. 23-08, dated July 29, 2008 13. Tublay 5th IFUGAO 1 Aguinaldo 2nd 2 Alfonso Lista 3rd 3 Asipulo 5th 4 Banaue 4th 5 Hingyon 5th 6 Hungduan 4th 7 Kiangan 4th 8 Lagawe 4th 9 Lamut 4th 10 Mayoyao 4th 11 Tinoc 4th KALINGA 1. Balbalan 3rd 2. Lubuagan 4th 3. Pasil 5th 4. Pinukpuk 1st 5. Rizal 4th 6. Tanudan 4th 7. Tinglayan 4th MOUNTAIN PROVINCE 1. Barlig 5th 2. Bauko 4th 3. Besao 5th 4. -

Abraexecutivesummary.Pdf

Submitted to: Submitted by: DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES BERKMAN INTERNATIONAL,INC. DENR Main Building, Visayas Avenue 3/F, VAG Building, Ortigas Avenue Diliman, Quezon City Greenhills, San Juan City, Philippines Tel. Nos.: (632) 721-9123; 721-9129 Fax No.: (632) 721-4219 www.berkmaninternational.com JUNE 2015 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY VOLUME I Table of Contents I. Background ................................................................................................................................................ 1 II. Objectives of the Masterplan Project ....................................................................................................... 4 III. Development Trends and Plans in the basin............................................................................................ 5 The Abra and Tineg Rivers : A Situationer ................................................................................................ 5 Water-related Sectors - present situation .............................................................................................. 11 State of the Basin Watershed ................................................................................................................. 15 Biodiversity ............................................................................................................................................. 16 Climate Change Scenarios ....................................................................................................................... 16 Coastal -

Division-Memo-No.-247-S.-2017.Pdf

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Cordillera Administrative Region SCHOOLS DIVISION OF ABRA Bangued, Abra LIST OF ATHLETES, COACHES, AND CHAPERONE FOR 2018 CARAA I. ATHLETICS A. ELEMENTARY BOYS 1. BLAZA, JUSTINE LAWRENCE = BILABILA ES 2. DOMINGO, DENZEL MARK = NAGTIPULAN ES 3. BATOON, JOHN MARK = PACOC ES 4. MOLINA, JHOROS JAMES = LAYUGAN ES 5. BONILLA, JOROS ALVI = NAGTIPULAN ES 6. HERMOSO, JUNUEL = SAN RAMON ES 7. ZAPATA, LEBRON JAMES = DLORES CS 8. MONTERO, DENNIS KARLO = SAN ISIDRO ES 9. DACQUEL, JONATHAN = SAN RAMON ES 10. VILLAGANES,JOHN PAUL = PATOC ES 11. PECSON, JUSTIN JAMES = BAAY ES 12. BEROÑA, JAYLORD = TAPING ES 13. FONTANILLA, GREG ZANDER = PATOC ES 14. CABINTOY, CRISANTO = CARIDAD AZARES ES 15. VILLAMOR, JERALD = PAGANAO ES 16. DOMINGO, DENZEL MARK = NAGTIPULAN ES Coach: _______________ _________________ Co- Coach: _______________ _________________ B. ELEMENTARY GIRLS: 1. BLANES, KRIZELLE NAE = BAÑACAO ES 2. TUAZON, IZZY = DALALAGUISEN ES 3. ABOLI, JOVELYN. = AMTI ES 4. ROSARIO, HANA RAIAH = PACOC ES 5. MAPAOS, AREINE FAYE = DANAC ES 6. BLAZA, LEAH VENUS = DAIODAO ES 7. MOLINA, JONA MAE = SANTO TOMAS BARRIO SCHOOL 8. BILGERA SHARA MAE = DALAGUISEN ES 9. GABAN TRISHA MAE = LIGUIS ES 10. DIVINA, JONALYN = SAN RAMON ES 11. OYAY, ALTHEA = PAGANAO ES 12. ANAAS, CHARMEE KAYE = DILONG ES 13. MOLINA, MYKA LORINE = BUCAY CS 14. ALGARNE, REGINE = BAÑACAO ES 15. MARTINEZ, FENNY = SAN JUAN CENTRAL SCHOOL 16. BALAO-AS, PRINCESS = DANAC ES Coaches: __________________ = _____________________ Co-Coach: __________________ = _____________________ C. SECONDARY BOYS 1. CALIBUSO, JAMES = ASIST LAGANGILANG CAMPUS 2. PATUBO, JM = TAGODTOD NHS 3. BACAO, BREADEN = BOLINEY NHS 4. WACQUISAN, JANRAY = BAAY NHS – LACUB EXTENSION 5. -

Cordillera Administrative Region

` CORDILLERA ADMINISTRATIVE REGION I. REGIONAL OFFICE Room 111 Hall of Justice, Baguio City Telefax: (074) 244-2180 Email ADDress: [email protected] Janette S. Padua - Regional Officer-In-Charge (ROIC) Cosme D. Ibis, Jr. - CPPO/Special Assistant to the ROIC Anabelle T. Sab-it - Supervising Probation and Parole Officer/CSU Head Nely B. Wayagwag - Supervising Probation and Parole Officer/CMRU Head Kirk John S. Yapyapan - Administrative Officer IV/Acting Accountant Mur Lee C. Quezon - Administrative Officer II/BuDget Officer Redentor R. Ambanloc - Probation anD Parole Officer I/Assistant CMRU Ma. Christina R. Del Rosario - Administrative Officer I Kimberly O. Lopez - Administrative AiDe VI/Acting Property Officer Cleo B. Ballo - Job Order Personnel Aledehl Leslie P. Rivera - Job Order Personnel Ronabelle C. Sanoy - Job Order Personnel Monte Carlo P. Castillo - Job Order Personnel Karl Edrenne M. Rivera - Job Order Personnel II. CITY BAGUIO CITY PAROLE AND PROBATION OFFICE Room 109 Hall of Justice, Baguio City Telefax: (074) 244-8660 Email ADDress: [email protected] PERSONNEL COMPLEMENT Daisy Marie S. Villanueva - Chief Probation and Parole Officer Anabelle T. Sab-it - Supervising Probation and Parole Officer/CSU Head Nely B. Wayagwag - Supervising Probation and Parole Officer/CMRU Head Mary Ann A. Bunaguen - Senior Probation and Parole Officer Anniebeth B. TriniDad - Probation and Parole Officer II Romuella C. Quezon - Probation and Parole Officer II Maria Grace D. Delos Reyes - Probation and Parole Officer I Josefa V. Bilog - Job Order Personnel Kristopher Picpican - Job Order Personnel AREAS OF JURISDICTION 129 Barangays of Baguio City COURTS SERVED RTC Branches 3 to 7 - Baguio City Branches 59 to 61 - Baguio City MTCC Branches 1 to 4 - Baguio City III. -

Heirloom Recipes of the Cordillera

Heirloom Recipes of the Cordillera Partners for Indigenous Knowledge Philippines HEIRLOOM RECIPES OF THE CORDILLERA Philippine Copyright 2019 Philippine Task Force for Indigenous People’s Rights (TFIP) Partners for Indigenous Knowledge Philippines (PIKP) This work is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial License (CC BY-NC). Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purpose is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holders. Published by: Philippine Task Force for Indigenous People’s Rights (TFIP) #16 Loro Street, Dizon Subdivision, Baguio City, Philippines And Partners for Indigenous Knowledge Philippines (PIKP) #54 Evangelista Street, Leonila Hill, Baguio City, Philippines With support from: VOICE https://voice.global Editor: Judy Cariño-Fangloy Illustrations: Sixto Talastas & Edward Alejandro Balawag Cover: Edward Alejandro Balawag Book design and layout: Ana Kinja Tauli Project Team: Marciana Balusdan Jill Cariño Judy Cariño-Fangloy Anna Karla Himmiwat Maria Elena Regpala Sixto Talastas Ana Kinja Tauli ISBN: 978-621-96088-0-0 To the next generation, May they inherit the wisdom of their ancestors Contents Introduction 1 Rice 3 Roots 39 Vegetables 55 Fish, Snails and Crabs 89 Meat 105 Preserves 117 Drinks 137 Our Informants 153 Foreword This book introduces readers to foods eaten and shared among families and communities of indigenous peoples in the Cordillera region of the Philippines. Heirloom recipes were generously shared and demonstrated by key informants from Benguet, Ifugao, Mountain Province, Kalinga and Apayao during food and cooking workshops in Conner, Besao, Sagada, Bangued, Dalupirip and Baguio City. -

Survey and Documentation of the Isnags Traditional Farming Tools and Implements

Asia Pacific Journal of Education, Arts and Sciences | Vol. 1, No. 1 | March 2014 _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Survey and Documentation of the Isnags Traditional Farming Tools and Implements RONALD O. OCAMPO [email protected] Apayao State College, San Isidro Sur, Luna, Apayao PHILIPPINES Abstract - This study was conducted to document farming on the lower stream. The Immadayas occupy the town tools and implements of the Isnags of Apayao. The study made Calanasan while the Immalud occupy the towns of Kabugao used of the descriptive survey method of research with key and Lower Apayao. informant interview and documentation as primary data Very little is known about how the Isnags lived before the gathering tools. The Isnags are bounded with beliefs and Spaniards came to the Philippines. It is probable that they lived practices in all walks of their life. In the performance of these much as they do today — by hunting, fishing, and kaingin beliefs and practices, some of their farming tools are being farming/That there was direct or indirect trade with China is utilized. A popular festival featuring ethnic songs , dances and evidenced by the Chinese jars, plates, and beads that are prized rituals called the Say-am is being performed as a means of possession of many Isnag families. preserving their unique cultural traditions. The aliwa is used Agriculture has been their major occupation since time in the performance of a ritual as they cut the head of a dog or a immemorial. The Isnags brought with them their important pig to be used during say-am. After the say-am is the giving of material culture as evidenced in the towering palms in their food wrap in banana or “samak” leaves signifying the settlements. -

August 2018 PECI Activities

Republic of the Philippines Office of the President PHILIPPINE DRUG ENFORCEMENT AGENCY Regional Office CAR Camp Bado Dangwa, La Trinidad 2601, Benguet [email protected] (074) 422-5544 August 2018 PECI Activities a. Consultative Meeting with MLGOO, Tayum, ABRA On August 6, 2018, Atty. Joseph Calulut together with IAV Julius Paderes, PO, PDEA-Abra attended the meeting with MLGOO at Tayum, Abra. b. Guest Speakership On August 6, 2018, IAV Julius Paderes PO, PDEA-Abra attended the Graduation Rites and served as the Guest Speaker to the 56 clients who underwent the six (6) months Community Based Drug Rehabilitation held at Langiden, Abra. c. Lecture on RA 9165 On August 6, 2018, Atty. Joseph Calulut, PIO, PDEA-CAR conducted lecture on RA 9165 to 311 participants including 56 members who graduated in the six (6) months Community Based Drug Rehabilitation held at Langiden, Abra. Page 1 of 8 d. Graduation Rites On August 6, 2018, Atty. Joseph Calulut, PIO, PDEA-CAR together with IAV Julius Paderes PO, PDEA-Abra attended the Graduation Rites of the 56 clients who underwent the Community Based Drug Rehabilation in Langiden, Abra. The said activity was attended by 255 participants from different LGU’s of Abra Province. e. Dialogue at Tayum, Abra On August 6, 2018, Atty. Joseph Calulut together with IAV Julius Paderes, PO, PDEA-Abra attended a meeting held at Tayum, Abra. The said meeting was attended by 33 participants from different Barangays in Abra. f. Consultative Meeting with DILG Provincial Director On August 6, 2018, Atty. Joseph Calulut together with IAV Julius Paderes, PO, PDEA ABRA attended the Consultative meeting with Director Millicent Cariño, DILG-ABRA, Provincial Director held at DILG-ABRA Office. -

A. Mining Tenement Applications 1

MPSA Republic of the Philippines Department of Environment and Natural Resources MINES AND GEOSCIENCES BUREAU - CORDILLERA ADMINISTRATIVE REGION MINING TENEMENTS STATISTICS REPORT FOR MONTH OF JULY 2021 MINERAL PRODUCTION SHARING AGREEMENT (MPSA) ANNEX-B %Ownership of Major SEQ HOLDER WITHIN PARCEL TEN Filipino and Foreign DATE FILED DATE APPROVED APPRVD (Integer no. of TENEMENT NO (Name, Authorized Representative with AREA (has.) MUNICIPALITY PROVINCE COMMODITY MINERAL REMARKS No. TYPE Person(s) with (mm/dd/yyyy) (mm/dd/yyyy) (T/F) TENEMENT NO) designation, Address, Contact details) RES. (T/F) Nationality A. Mining Tenement Applications 1. Under Process Shipside, Inc., Buguias, Beng.; With MAB - Case with Cordillera Atty. Pablo T. Ayson, Jr., Tinoc, Ifugao; Bauko Benguet & Mt. 49 APSA-0049-CAR APSA 4,131.0000 22-Dec-1994 Gold F F Exploration, Inc. formerly NPI Atty in fact, BA-Lepanto Bldg., & Tadian, Mt. Province (MGB Case No. 013) 8747 Paseo de Roxas, Makati City Province Jaime Paul Panganiban Wrenolph Panaganiban Case with EXPA No. 085 - with Court of Gold, Copper, 63 APSA-0063-CAR APSA Authorized Representative 85.7200 11-Aug-1997 Mankayan Benguet F F Appeals (Case No. C.A.-G.R. SP No. Silver AC 152, East Buyagan, La Trinidad, 127172) Benguet June Prill Brett James Wallace P. Brett, Jr. Case with EXPA No. 085 - with Court of Gold, Copper, 64 APSA-0064-CAR APSA Authorized Representative. 98.7200 11-Aug-1997 Mankayan Benguet F F Appeals (Case No. C.A.-G.R. SP No. Silver #1 Green Mansions Rd. 127172) Mines View Park, B.C. Itogon Suyoc Resoucres, Inc. -

Construction of Tayum Fire Station, Abra

PHILIPPINE BIDDING DOCUMENTS Construction of Tayum Fire Station, Abra Government of the Republic of the Philippines BFP CAR ITB No. 04 s. 2021 Sixth Edition July 2020 Preface These Philippine Bidding Documents (PBDs) for the procurement of Infrastructure Projects (hereinafter referred to also as the “Works”) through Competitive Bidding have been prepared by the Government of the Philippines for use by all branches, agencies, departments, bureaus, offices, or instrumentalities of the government, including government- owned and/or -controlled corporations, government financial institutions, state universities and colleges, local government units, and autonomous regional government. The procedures and practices presented in this document have been developed through broad experience, and are for mandatory use in projects that are financed in whole or in part by the Government of the Philippines or any foreign government/foreign or international financing institution in accordance with the provisions of the 2016 revised Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR) of Republic Act (RA) No. 9184. The PBDs are intended as a model for admeasurements (unit prices or unit rates in a bill of quantities) types of contract, which are the most common in Works contracting. The Bidding Documents shall clearly and adequately define, among others: (i) the objectives, scope, and expected outputs and/or results of the proposed contract; (ii) the eligibility requirements of Bidders; (iii) the expected contract duration; and (iv)the obligations, duties, and/or functions of the winning Bidder. Care should be taken to check the relevance of the provisions of the PBDs against the requirements of the specific Works to be procured. If duplication of a subject is inevitable in other sections of the document prepared by the Procuring Entity, care must be exercised to avoid contradictions between clauses dealing with the same matter. -

Cordillera Administrative Region

` CORDILLERA ADMINISTRATIVE REGION I. REGIONAL OFFICE Room 111 Hall of Justice, Baguio City Telefax: (074) 244-2180 / 09237369805 Email Address: [email protected] Belinda C. Zafra - Regional Director Janette S. Padua - Assistant Regional Director Anabelle T. Sab-it - Supervising Probation and Parole Officer/CSU Head Nely B. Wayagwag - Supervising Probation and Parole Officer/CMRU Head Kirk John S. Yapyapan - Administrative Officer IV/Acting Accountant Mur Lee C. Quezon - Administrative Officer II/Budget Officer Redentor R. Ambanloc - Probation and Parole Officer I/Assistant CMRU Ma. Christina R. Del Rosario - Administrative Officer I Kimberly O. Lopez - Administrative Aide VI/Acting Property Officer Cleo B. Ballo - Job Order Personnel Aledehl Leslie P. Rivera - Job Order Personnel Ronabelle C. Sanoy - Job Order Personnel Monte Carlo P. Castillo - Job Order Personnel Karl Edrenne M. Rivera - Job Order Personnel II. CITY BAGUIO CITY PAROLE AND PROBATION OFFICE Room 109 Hall of Justice, Baguio City Telefax: (074) 244-8660 Email Address: [email protected] PERSONNEL COMPLEMENT Daisy Marie S. Villanueva - Chief Probation and Parole Officer Anabelle T. Sab-it - Supervising Probation and Parole Officer/CSU Head Nely B. Wayagwag - Supervising Probation and Parole Officer/CMRU Head Mary Ann A. Bunaguen - Senior Probation and Parole Officer Anniebeth B. Trinidad - Probation and Parole Officer II Romuella C. Quezon - Probation and Parole Officer II Maria Grace D. Delos Reyes - Probation and Parole Officer I Kristopher Picpican - Job Order Personnel Josefa V. Bilog - Job Order Personnel AREAS OF JURISDICTION 129 Barangays of Baguio City COURTS SERVED RTC Branches 3 to 7 - Baguio City Branches 59 to 61 - Baguio City MTCC Branches 1 to 4 - Baguio City III. -

In the Matter of the Application For

Republic of the Philippines ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION Pacific Center Building San Miguel Avenue, Pasig City IN THE MATTER OF THE APPLICATION FOR APROVAL OF CAPITAL EXPENDITURE PROJECT FOR 2020, NAMELY: PURCHASE AND INSTALLATION OF NEW 10 MVA POWER TRANSFORMER FOR CALABA SUBSTATION ERC CASE NO. 2021-039_______ RC May 27, 2021 ABRA ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE (ABRECO), Applicant. x - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - x APPLICATION APPLICANT, ABRA ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE (ABRECO) thru counsel, unto this Honorable Commission, most respectfully alleges that: THE APPLICANT 1. ABRECO is an electric cooperative duly organized and existing by virtue of the laws of the Republic of the Philippines, with principal office address at Calaba, Bangued, Abra; 2. It holds an exclusive franchise issued by the National Electrification Commission to operate an electric light and power distribution service in the twenty-seven (27) municipalities of the province of Abra, namely: Bangued, Baay-Licuan, Boliney, Bucay, Bucloc, Daguioman, Danglas, Dolores, Lacub, Lagangilang, Lagayan, 1 | P a g e La Paz, Langiden, Luba, Malibcong, Manabo, Peñarrubia, Pidigan, Pilar, Sallapadan, San Isidro, San Juan, San Quintin, Tayum, Tineg, Tubo and Villaviciosa. LEGAL BASES FOR THE APPLICATION 3. Pursuant to Republic Act No. 9136, ERC Resolution 26, Series of 2009 and other laws and rules, and in line with its mandate to provide safe, quality, efficient and reliable electric service to electric consumers in its franchise area, ABRECO submits the instant application for the Honorable Commission’s consideration, permission and approval of its Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) Project for 2020, namely: Purchase and Installation of New 10 MVA Power Transformer for its Calaba Substation located at Brgy.