Buneg, Lacub, Abra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Province of Apayao

! 120°50' 121°0' 121°10' 121°20' 121°30' R E P U B L I C O F T H E P H I L I P P I N E S D E PA R T M E N T O F A G R I C U LT U R E 18°30' BUREAU OF SOILS AND WATER MANAG EMENT 18°30' Elliptical Road,cor.Visa yas Ave.,Diliman,Que zon City SOIL ph MAP ( Key Rice Areas ) PROVINCE OF APAYAO Abulug ! ° SCALE 1 : 100 , 000 0 1 2 4 6 8 10 Kilometers Ballesteros Projection : BallesteTraon!ssverse Mercator ! Datum : Luzon 1911 DISCLAIMER: All political boundaries are not authoritative 18°20' Luna ! 18°20' Santa Marcela ! Province of Ilocos Norte Calanasan ! Pudtol ! Flora ! 18°10' Province of Cagayan 18°10' ! KABUGAO P 18°0' 18°0' LEGEND pH Value GENERAL AREA MAPPING UNIT DESCRIPTION ( 1:1 RATIO ) RATING ha % Nearly Neutral - - > 6.8 or to Extremely Alkaline - - Low - - < 4.5 Extremely Acid - - Moderately Very Strongly - - 4.6 - 5.0 Low Acid - - Moderately 2 ,999 1 0.98 5.1 - 5.5 Strongly Acid Province of Cagayan High 2 ,489 9 .12 Moderately 7 ,474 2 7.37 5.6 - 6.8 High Acid to Slightly Acid 1 4,341 5 2.53 Province of Abra T O T A L 27,303 100.00 17°50' Paddy Irrigated Paddy Non Irrigated 17°50' Arreae aes trimefaeterds b taose tdh oen aacctutuala file aldr seurav esyu, ortvhery inefdor mbyat itohne fr ofmie lDdA -sRuFOr'vs,e MyA t'es,a NmIA. -

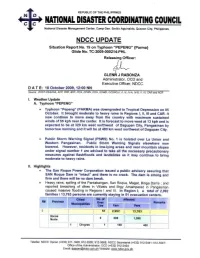

NDCC Update Sitrep No. 19 Re TY Pepeng As of 10 Oct 12:00NN

2 Pinili 1 139 695 Ilocos Sur 2 16 65 1 Marcos 2 16 65 La Union 35 1,902 9,164 1 Aringay 7 570 3,276 2 Bagullin 1 400 2,000 3 Bangar 3 226 1,249 4 Bauang 10 481 1,630 5 Caba 2 55 193 6 Luna 1 4 20 7 Pugo 3 49 212 8 Rosario 2 30 189 San 9 Fernand 2 10 43 o City San 10 1 14 48 Gabriel 11 San Juan 1 19 111 12 Sudipen 1 43 187 13 Tubao 1 1 6 Pangasinan 12 835 3,439 1 Asingan 5 114 458 2 Dagupan 1 96 356 3 Rosales 2 125 625 4 Tayug 4 500 2,000 • The figures above may continue to go up as reports are still coming from Regions I, II and III • There are now 299 reported casualties (Tab A) with the following breakdown: 184 Dead – 6 in Pangasinan, 1 in Ilocos Sur (drowned), 1 in Ilocos Norte (hypothermia), 34 in La Union, 133 in Benguet (landslide, suffocated secondary to encavement), 2 in Ifugao (landslide), 2 in Nueva Ecija, 1 in Quezon Province, and 4 in Camarines Sur 75 Injured - 1 in Kalinga, 73 in Benguet, and 1 in Ilocos Norte 40 Missing - 34 in Benguet, 1 in Ilocos Norte, and 5 in Pangasinan • A total of 20,263 houses were damaged with 1,794 totally and 18,469 partially damaged (Tab B) • There were reports of power outages/interruptions in Regions I, II, III and CAR. Government offices in Region I continue to be operational using generator sets. -

Income Classification Per DOF Order No. 23-08, Dated July 29, 2008 MUNICIPALITIES Classification NCR 1

Income Classification Per DOF Order No. 23-08, dated July 29, 2008 MUNICIPALITIES Classification NCR 1. Pateros 1st CAR ABRA 1 Baay-Licuan 5th 2 Bangued 1st 3 Boliney 5th 4 Bucay 5th 5 Bucloc 6th 6 Daguioman 5th 7 Danglas 5th 8 Dolores 5th 9 La Paz 5th 10 Lacub 5th 11 Lagangilang 5th 12 Lagayan 5th 13 Langiden 5th 14 Luba 5th 15 Malibcong 5th 16 Manabo 5th 17 Penarrubia 6th 18 Pidigan 5th 19 Pilar 5th 20 Sallapadan 5th 21 San Isidro 5th 22 San Juan 5th 23 San Quintin 5th 24 Tayum 5th 25 Tineg 2nd 26 Tubo 4th 27 Villaviciosa 5th APAYAO 1 Calanasan 1st 2 Conner 2nd 3 Flora 3rd 4 Kabugao 1st 5 Luna 2nd 6 Pudtol 4th 7 Sta. Marcela 4th BENGUET 1. Atok 4th 2. Bakun 3rd 3. Bokod 4th 4. Buguias 3rd 5. Itogon 1st 6. Kabayan 4th 7. Kapangan 4th 8. Kibungan 4th 9. La Trinidad 1st 10. Mankayan 1st 11. Sablan 5th 12. Tuba 1st blgf/ltod/updated 1 of 30 updated 4-27-16 Income Classification Per DOF Order No. 23-08, dated July 29, 2008 13. Tublay 5th IFUGAO 1 Aguinaldo 2nd 2 Alfonso Lista 3rd 3 Asipulo 5th 4 Banaue 4th 5 Hingyon 5th 6 Hungduan 4th 7 Kiangan 4th 8 Lagawe 4th 9 Lamut 4th 10 Mayoyao 4th 11 Tinoc 4th KALINGA 1. Balbalan 3rd 2. Lubuagan 4th 3. Pasil 5th 4. Pinukpuk 1st 5. Rizal 4th 6. Tanudan 4th 7. Tinglayan 4th MOUNTAIN PROVINCE 1. Barlig 5th 2. Bauko 4th 3. Besao 5th 4. -

One Big File

MISSING TARGETS An alternative MDG midterm report NOVEMBER 2007 Missing Targets: An Alternative MDG Midterm Report Social Watch Philippines 2007 Report Copyright 2007 ISSN: 1656-9490 2007 Report Team Isagani R. Serrano, Editor Rene R. Raya, Co-editor Janet R. Carandang, Coordinator Maria Luz R. Anigan, Research Associate Nadja B. Ginete, Research Assistant Rebecca S. Gaddi, Gender Specialist Paul Escober, Data Analyst Joann M. Divinagracia, Data Analyst Lourdes Fernandez, Copy Editor Nanie Gonzales, Lay-out Artist Benjo Laygo, Cover Design Contributors Isagani R. Serrano Ma. Victoria R. Raquiza Rene R. Raya Merci L. Fabros Jonathan D. Ronquillo Rachel O. Morala Jessica Dator-Bercilla Victoria Tauli Corpuz Eduardo Gonzalez Shubert L. Ciencia Magdalena C. Monge Dante O. Bismonte Emilio Paz Roy Layoza Gay D. Defiesta Joseph Gloria This book was made possible with full support of Oxfam Novib. Printed in the Philippines CO N T EN T S Key to Acronyms .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. iv Foreword.................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... vii The MDGs and Social Watch -

Cordillera Administrative Region

` CORDILLERA ADMINISTRATIVE REGION I. REGIONAL OFFICE Room 111 Hall of Justice, Baguio City Telefax: (074) 244-2180 Email ADDress: [email protected] Janette S. Padua - Regional Officer-In-Charge (ROIC) Cosme D. Ibis, Jr. - CPPO/Special Assistant to the ROIC Anabelle T. Sab-it - Supervising Probation and Parole Officer/CSU Head Nely B. Wayagwag - Supervising Probation and Parole Officer/CMRU Head Kirk John S. Yapyapan - Administrative Officer IV/Acting Accountant Mur Lee C. Quezon - Administrative Officer II/BuDget Officer Redentor R. Ambanloc - Probation anD Parole Officer I/Assistant CMRU Ma. Christina R. Del Rosario - Administrative Officer I Kimberly O. Lopez - Administrative AiDe VI/Acting Property Officer Cleo B. Ballo - Job Order Personnel Aledehl Leslie P. Rivera - Job Order Personnel Ronabelle C. Sanoy - Job Order Personnel Monte Carlo P. Castillo - Job Order Personnel Karl Edrenne M. Rivera - Job Order Personnel II. CITY BAGUIO CITY PAROLE AND PROBATION OFFICE Room 109 Hall of Justice, Baguio City Telefax: (074) 244-8660 Email ADDress: [email protected] PERSONNEL COMPLEMENT Daisy Marie S. Villanueva - Chief Probation and Parole Officer Anabelle T. Sab-it - Supervising Probation and Parole Officer/CSU Head Nely B. Wayagwag - Supervising Probation and Parole Officer/CMRU Head Mary Ann A. Bunaguen - Senior Probation and Parole Officer Anniebeth B. TriniDad - Probation and Parole Officer II Romuella C. Quezon - Probation and Parole Officer II Maria Grace D. Delos Reyes - Probation and Parole Officer I Josefa V. Bilog - Job Order Personnel Kristopher Picpican - Job Order Personnel AREAS OF JURISDICTION 129 Barangays of Baguio City COURTS SERVED RTC Branches 3 to 7 - Baguio City Branches 59 to 61 - Baguio City MTCC Branches 1 to 4 - Baguio City III. -

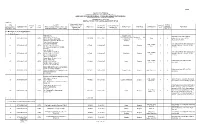

Region Penro Cenro Municipality Barangay

AREA IN REGION PENRO CENRO MUNICIPALITY BARANGAY DISTRICT NAME OF ORGANIZATION TYPE OF ORGANIZATION SPECIES COMMODITY COMPONENT YEAR ZONE TENURE WATERSHED SITECODE REMARKS HECTARES CAR Abra Bangued Sallapadan Ududiao Lone District 50.00 UDNAMA Highland Association Inc. PO Coffee Coffee Agroforestry 2017 Production Untenured Abra River Watershed 17-140101-0001-0050 CAR Abra Bangued Boliney Amti Lone District 50.00 Amti Minakaling Farmers Association PO Coffee Coffee Agroforestry 2017 Production Untenured Abra River Watershed 17-140101-0002-0050 CAR Abra Bangued Boliney Danac east Lone District 97.00 Nagsingisinan Farmers Association PO Coffee Coffee Agroforestry 2017 Production Untenured Abra River Watershed 17-140101-0003-0097 CAR Abra Bangued Boliney Danac West Lone District 100.00 Danac Pagrang-ayan Farmers Tree Planters Association PO Coffee Coffee Agroforestry 2017 Production Untenured Abra River Watershed 17-140101-0004-0100 CAR Abra Bangued Daguioman Cabaruyan Lone District 50.00 Cabaruyan Daguioman Farmers Association PO Coffee Coffee Agroforestry 2017 Production Untenured Abra River Watershed 17-140101-0005-0050 CAR Abra Bangued Boliney Kilong-olao Lone District 100.00 Kilong-olao Boliney Farmers Association Inc. PO Coffee Coffee Agroforestry 2017 Production Untenured Abra River Watershed 17-140101-0006-0100 CAR Abra Bangued Sallapadan Bazar Lone District 50.00 Lam aoan Gayaman Farmers Association PO Coffee Coffee Agroforestry 2017 Production Untenured Abra River Watershed 17-140101-0007-0050 CAR Abra Bangued Bucloc Lingey Lone -

Heirloom Recipes of the Cordillera

Heirloom Recipes of the Cordillera Partners for Indigenous Knowledge Philippines HEIRLOOM RECIPES OF THE CORDILLERA Philippine Copyright 2019 Philippine Task Force for Indigenous People’s Rights (TFIP) Partners for Indigenous Knowledge Philippines (PIKP) This work is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial License (CC BY-NC). Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purpose is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holders. Published by: Philippine Task Force for Indigenous People’s Rights (TFIP) #16 Loro Street, Dizon Subdivision, Baguio City, Philippines And Partners for Indigenous Knowledge Philippines (PIKP) #54 Evangelista Street, Leonila Hill, Baguio City, Philippines With support from: VOICE https://voice.global Editor: Judy Cariño-Fangloy Illustrations: Sixto Talastas & Edward Alejandro Balawag Cover: Edward Alejandro Balawag Book design and layout: Ana Kinja Tauli Project Team: Marciana Balusdan Jill Cariño Judy Cariño-Fangloy Anna Karla Himmiwat Maria Elena Regpala Sixto Talastas Ana Kinja Tauli ISBN: 978-621-96088-0-0 To the next generation, May they inherit the wisdom of their ancestors Contents Introduction 1 Rice 3 Roots 39 Vegetables 55 Fish, Snails and Crabs 89 Meat 105 Preserves 117 Drinks 137 Our Informants 153 Foreword This book introduces readers to foods eaten and shared among families and communities of indigenous peoples in the Cordillera region of the Philippines. Heirloom recipes were generously shared and demonstrated by key informants from Benguet, Ifugao, Mountain Province, Kalinga and Apayao during food and cooking workshops in Conner, Besao, Sagada, Bangued, Dalupirip and Baguio City. -

People's Integrated Farm

January-June 2016 Volume 2, Issue 1 BinnadangThe official publication of the Center for Development Programs in the Cordillera People’s Integrated Farm Binnadang is the official publication of the Center for Development Programs in the Cordillera. Binnadang is a word used by the Bontoc Kankana-ey in the Cordillera, northern Philippines for labour cooperation. This concerted action by community members is mainly applied in agriculture and community gatherings. BinnadangSTAFF Jane Lingbawan-Yap-eo Executive Director Ann Loreto Tamayo Editor Blessy Jane Eslao Dina Manggad Honoria Fag-ayan Glen Ngolab Jerry Gittabao Julie Mero Marvin Canyas Research and Write-up Angelica Maye Lingbawan Yap-eo Lay out and Cover Design Photos by CDPC The contents of this publication may be referred to or reproduced without the permission of CDPC as long as the source is duly ac- knowledged, reference is accurate, reproduction is in good faith, and the work is properly cited. This publication is supported by SOLIDAGRO and the Province of East Flanders (PEF), Belgium. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of SOLIDA- GRO and PEF. Contact Details Center for Development Programs in the Cordillera, Inc. (CDPC) #362 Cathedral of the Resurrection Church (EDNCP) compound Lower Magsaysay Avenue, Baguio City 2600, Cordillera Administrative Region, Northern Luzon, Philippines [email protected]; [email protected] [email protected] Telefax No: (+63) (74) 424-3764 cdpckordilyera.org Printed by: Valley Printing Specialist Baguio City CONTENTS 4 The Cordillera Peoples 15 Organic Farm Salidummay from Limos 11 Belgian Farmers see Development at Work January-June 2016 Binnadang 1 22 Community Agroforestry: A shared, not cash-driven, responsibility 18 Community-based Health Program, the Lacub Experience Water Flows 27 for Calaccad 34 30 Reflections of a K-12 Program: Its Impacts development worker and Challenges 2 Binnadang January-June 2016 editorial MILITARIZING DEVELOPMENT n the “battle to win hearts and minds,” the military are undergoing a grand makeover. -

A. Mining Tenement Applications 1

MPSA Republic of the Philippines Department of Environment and Natural Resources MINES AND GEOSCIENCES BUREAU - CORDILLERA ADMINISTRATIVE REGION MINING TENEMENTS STATISTICS REPORT FOR MONTH OF JULY 2021 MINERAL PRODUCTION SHARING AGREEMENT (MPSA) ANNEX-B %Ownership of Major SEQ HOLDER WITHIN PARCEL TEN Filipino and Foreign DATE FILED DATE APPROVED APPRVD (Integer no. of TENEMENT NO (Name, Authorized Representative with AREA (has.) MUNICIPALITY PROVINCE COMMODITY MINERAL REMARKS No. TYPE Person(s) with (mm/dd/yyyy) (mm/dd/yyyy) (T/F) TENEMENT NO) designation, Address, Contact details) RES. (T/F) Nationality A. Mining Tenement Applications 1. Under Process Shipside, Inc., Buguias, Beng.; With MAB - Case with Cordillera Atty. Pablo T. Ayson, Jr., Tinoc, Ifugao; Bauko Benguet & Mt. 49 APSA-0049-CAR APSA 4,131.0000 22-Dec-1994 Gold F F Exploration, Inc. formerly NPI Atty in fact, BA-Lepanto Bldg., & Tadian, Mt. Province (MGB Case No. 013) 8747 Paseo de Roxas, Makati City Province Jaime Paul Panganiban Wrenolph Panaganiban Case with EXPA No. 085 - with Court of Gold, Copper, 63 APSA-0063-CAR APSA Authorized Representative 85.7200 11-Aug-1997 Mankayan Benguet F F Appeals (Case No. C.A.-G.R. SP No. Silver AC 152, East Buyagan, La Trinidad, 127172) Benguet June Prill Brett James Wallace P. Brett, Jr. Case with EXPA No. 085 - with Court of Gold, Copper, 64 APSA-0064-CAR APSA Authorized Representative. 98.7200 11-Aug-1997 Mankayan Benguet F F Appeals (Case No. C.A.-G.R. SP No. Silver #1 Green Mansions Rd. 127172) Mines View Park, B.C. Itogon Suyoc Resoucres, Inc. -

Cordillera Administrative Region

` CORDILLERA ADMINISTRATIVE REGION I. REGIONAL OFFICE Room 111 Hall of Justice, Baguio City Telefax: (074) 244-2180 / 09237369805 Email Address: [email protected] Belinda C. Zafra - Regional Director Janette S. Padua - Assistant Regional Director Anabelle T. Sab-it - Supervising Probation and Parole Officer/CSU Head Nely B. Wayagwag - Supervising Probation and Parole Officer/CMRU Head Kirk John S. Yapyapan - Administrative Officer IV/Acting Accountant Mur Lee C. Quezon - Administrative Officer II/Budget Officer Redentor R. Ambanloc - Probation and Parole Officer I/Assistant CMRU Ma. Christina R. Del Rosario - Administrative Officer I Kimberly O. Lopez - Administrative Aide VI/Acting Property Officer Cleo B. Ballo - Job Order Personnel Aledehl Leslie P. Rivera - Job Order Personnel Ronabelle C. Sanoy - Job Order Personnel Monte Carlo P. Castillo - Job Order Personnel Karl Edrenne M. Rivera - Job Order Personnel II. CITY BAGUIO CITY PAROLE AND PROBATION OFFICE Room 109 Hall of Justice, Baguio City Telefax: (074) 244-8660 Email Address: [email protected] PERSONNEL COMPLEMENT Daisy Marie S. Villanueva - Chief Probation and Parole Officer Anabelle T. Sab-it - Supervising Probation and Parole Officer/CSU Head Nely B. Wayagwag - Supervising Probation and Parole Officer/CMRU Head Mary Ann A. Bunaguen - Senior Probation and Parole Officer Anniebeth B. Trinidad - Probation and Parole Officer II Romuella C. Quezon - Probation and Parole Officer II Maria Grace D. Delos Reyes - Probation and Parole Officer I Kristopher Picpican - Job Order Personnel Josefa V. Bilog - Job Order Personnel AREAS OF JURISDICTION 129 Barangays of Baguio City COURTS SERVED RTC Branches 3 to 7 - Baguio City Branches 59 to 61 - Baguio City MTCC Branches 1 to 4 - Baguio City III. -

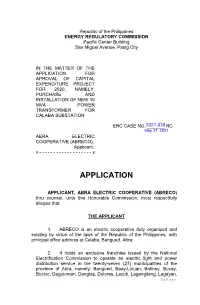

In the Matter of the Application For

Republic of the Philippines ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION Pacific Center Building San Miguel Avenue, Pasig City IN THE MATTER OF THE APPLICATION FOR APROVAL OF CAPITAL EXPENDITURE PROJECT FOR 2020, NAMELY: PURCHASE AND INSTALLATION OF NEW 10 MVA POWER TRANSFORMER FOR CALABA SUBSTATION ERC CASE NO. 2021-039_______ RC May 27, 2021 ABRA ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE (ABRECO), Applicant. x - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - x APPLICATION APPLICANT, ABRA ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE (ABRECO) thru counsel, unto this Honorable Commission, most respectfully alleges that: THE APPLICANT 1. ABRECO is an electric cooperative duly organized and existing by virtue of the laws of the Republic of the Philippines, with principal office address at Calaba, Bangued, Abra; 2. It holds an exclusive franchise issued by the National Electrification Commission to operate an electric light and power distribution service in the twenty-seven (27) municipalities of the province of Abra, namely: Bangued, Baay-Licuan, Boliney, Bucay, Bucloc, Daguioman, Danglas, Dolores, Lacub, Lagangilang, Lagayan, 1 | P a g e La Paz, Langiden, Luba, Malibcong, Manabo, Peñarrubia, Pidigan, Pilar, Sallapadan, San Isidro, San Juan, San Quintin, Tayum, Tineg, Tubo and Villaviciosa. LEGAL BASES FOR THE APPLICATION 3. Pursuant to Republic Act No. 9136, ERC Resolution 26, Series of 2009 and other laws and rules, and in line with its mandate to provide safe, quality, efficient and reliable electric service to electric consumers in its franchise area, ABRECO submits the instant application for the Honorable Commission’s consideration, permission and approval of its Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) Project for 2020, namely: Purchase and Installation of New 10 MVA Power Transformer for its Calaba Substation located at Brgy. -

SOIL Ph MAP 18°0' ( Key Rice Areas ) Province of Apayao PROVINCE of ABRA ° SCALE 1:220,000 0 2 4 6 8 10 12

121°0' R E P U B L I C O F T H E P H I L I P P I N E S D E PA R T M E N T O F A G R IIC U LT U R E BUREAU OF SOILS AND WATER MANAGEMENT Elliptical Road Cor. Visayas Ave., Diliman, Quezon City 18°0' SOIL pH MAP 18°0' ( Key Rice Areas ) Province of Apayao PROVINCE OF ABRA ° SCALE 1:220,000 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 Kilometers Projection : Transverse Mercator Datum : PRS 1992 DISCLAIMER : All political boundaries are not authoritative Province of Ilocos Norte !Tineg !Lagayan !Danglas !San Juan !La Paz !Lacub !Dolores !Tayum Licuan-Baay !Lagangilang ! Bangued P !Malibcong !Langiden !Pidigan !Peñarrubia !San Quintin !Bucay San Isidro ! Province of Kalinga !Daguioman !Sallapadan !Bucloc !Villaviciosa !Manabo !Pilar !Boliney Province of Ilocos Sur !Luba !Tubo Mt. Province LEGEND AREA pH Value GENERAL MAPPING UNIT DESCRIPTION (1:1 Ratio) RATING ha % Nearly Neutral to LOCATION MAP - - 6.9 and above; Extremely Alkaline, Low 18° 4.5 and below Extremely Acid Ilocos Norte Apayao 3,839 21.84 - - LUZON 4.6 - 5.0 Moderately Low Very Strongly Acid 15° 672 3.82 - - 5.1 - 5.5 Moderately High Strongly Acid Abra 2,164 12.31 Moderately acid to - - VISAYAS 10° 5.6-6.8 High Kalinga slightly acid 10,899 62.02 TOTAL 17,574 100.00 Ilocos Sur Paddy Irrigated Paddy Non Irrigated Mt. Province MINDANAO 5° Area estimated based on actual field survey, other information from DA-RFO's, MA's, NIA Service Area, 121° 120° 125° NAMRIA Land Cover (2010) and BSWM Land Use System Map MISCELLANEOUS INFORMATION SOURCES OF INFORMATION:Topographic information taken from NAMRIA Topographic CONVENTIONAL SIGNS Map at a scale of 1:50,000.