Engolo/Capoeira, Knocking-And-Kicking and Asafo Flag Dancing1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JUDO Under the Authority of the Bakersfield Judo Club

JUDO Under the Authority of the Bakersfield Judo Club Time: Tuesdays and Thursdays, 6:30 -8:00 PM Location: CSUB Wrestling Room Instructors: Michael Flachmann (4th Dan) Phone: 661-654-2121 Steve Walsh (1st Dan) Guest Instructors: Dale Kinoshita (5th Dan) Phone: (work) 834-7570 (home) 837-0152 Brett Sakamoto (4th Dan) Gustavo Sanchez (1st Dan) The Bakersfield Judo Club rd meets twice a week on 23 St / Hwy 178 Mondays and Thursdays from 7:00 to 9:00 PM. JUDO Club They practice under the 2207 ‘N’ Authority of Kinya th 22nd St Sakamoto, Rokudan (6 Degree Black Belt), at 2207 N St. ’ St Q ‘N’ St ‘ Chester Ave Truxtun Ave Etiquette: Salutations: Pronunciation: Ritsurei Standing Bow a = ah (baa) Zarei Sitting Bow e = eh (kettle) Seiza Sitting on Knees i = e (key) o = oh (hole) When to Bow: u = oo (cool) Upon entering or exiting the dojo. Upon entering or exiting the tatami. Definitions: Before class begins and after class ends. Judo “The Gentle Way” Before and after working with a partner. Judoka Judo Practitioner Sensei Instructor Where to sit: Dojo Practice Hall Kamiza (Upper Seat) for senseis. Kiotsuke ATTENTION! Shimoza (Lower Seat) for students. Rei Command to Bow Joseki – Right side of Shimoza Randori Free practice Shimoseki – Left side of Shimoza Uchi Komi “Fitting in” or “turning in” practice Judo Gi: Students must learn the proper Tatami Judo mat way to war the gi and obi. Students should Kiai Yell also wear zoris when not on the mat. Hajime Begin Matte STOP! Kata Fromal Exercises Tori Person practicing Students must have technique Uke Person being their own personal practiced on health and injury O Big or Major insurance. -

Class Schedule

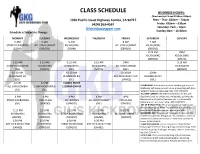

CLASS SCHEDULE BUSINESS HOURS: (Wednesdays Closed 1130am-330pm) 1930 Pacific Coast Highway Lomita, CA 90717 Mon – Thur: 830am – 730pm (424) 263-4567 Friday: 830am – 630pm Saturday: 7am – 12pm Gilskickboxinggym.com Sunday: 8am – 10:30am Schedule is Subject to Change. MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 6 AM 6 AM 6 AM 6 AM 7 AM STRAP KICKBOXING ALL GYM COMBAT KICKBOXING ALL GYM COMBAT KICKBOXING (JOHN) (SERGIO) (JOHN) (SERGIO) (SERGIO) 8:15 AM 8AM KICKBOXING KICKBOXING (SERGIO) (MAYA) 9:15 AM 9:15 AM 9:15 AM 9:15 AM 9AM 9:15 AM STRAP KICKBOXING KICKBOXING KICKBOXING KICKBOXING ALL GYM COMBAT KICKBOXING (GIL) (MAYA) (GIL) (MAYA) (GIL) (SERGIO) 10:30 AM 10:30 AM 10:30AM 10AM BEGINNERS BJJ BEGINNERS BJJ ART OF 8 MUAY THAI BEGINNERS BJJ (GIL) (GIL) (JAMES) (GIL) 12 PM 12 PM CLOSED FROM KICKBOXING: A 60-minute workout combining a series of ALL GYM COMBAT STRAP KICKBOXING 1130AM-330PM kickboxing techniques you will do on a heavy bag with body (Gil) (GIL) weight muscle endurance exercises. (NO CONTACT) ALL GYM COMBAT: We use the whole gym for this one. 4 PM 4 PM 4 PM 4 PM 4PM Equipment such as battle ropes, Kettlebells, agility ladder, Bungee cable, Grappling Dummies, etc. combined with STRAP KICKBOXING KIDS CLASS KICKBOXING ALL GYM COMBAT KIDS CLASS Kickboxing to train like a fighter. (NO CONTACT) (GIL) (SERGIO) (SERGIO) (GIL) (SERGIO) ART OF 8 MUAY THAI: This Class focuses on teaching you the fundamentals of Muay Thai Kickboxing. You will learn 5:15 PM 5:15 PM 5:15 PM 5:15 PM 5:15PM how to hold Thai pads and gain real striking skills. -

The Death of Dueling Wade Ellett

59 60 The Death of Dueling feuds, and a chivalric code of honor emphasizing virtue.6 Eventually this code of honor evolved into the upper class and nobility’s theory of courtesy and the idea of the “gentleman”. This resulted in the adoption of one-on-one combat to settle affairs in 7 the sixteenth century. The duel of honor, as recognized from entertainment media, was based primarily on the Italian Wade Ellett Renaissance idea of the gentleman and arrived in England in the 1570s.8 The practice was welcomed by the upper classes, who had Violence in some form or another has probably always long been awaiting a method to solve disputes. But the warm existed. Civilization did not end violence, it merely provided a reception was not shared by royalty, and Queen Elizabeth I framework to ritualize and institutionalize violent acts. Once outlawed the judicial duel in 1571.9 Her attempts to remove the civilized, ritual violence became almost entirely a man’s realm.1 practice from England failed and dueling quickly gained Ritual violence took many forms; but, without a doubt, one of the popularity.10 most romanticized was the duel. Dueling differed from wartime Dueling thrived in England for nearly three centuries; violence and barroom brawls because dueling placed two however, the practice eventually came to an end in 1852, when the opponents, almost always of similar social class, against one last recorded English duel was fought. There were many another in a highly stylized form of combat.2 Fisticuffs and war contributing factors to the practice’s end. -

World Combat Games Brochure

Table of Contents 4 5 6 What is GAISF? What are the World Roles and Combat Games? responsibilities 7 8 10 Attribution Culture, ceremonies Media promotion process and festival events, and production and legacy 12 13 14 List of sports Venue Aikido at the World setup Armwrestling Combat Games Boxing 15 16 17 Judo Kendo Muaythai Ju-jitsu Kickboxing Sambo Karate Savate 18 19 Sumo Wrestling Taekwondo Wushu 4 WORLD COMBAT GAMES WORLD COMBAT GAMES 5 What is GAISF? What are the World Combat Games? The united voice of sports - protecting the interests of International A breathtaking event, showcasing Federations the world’s best martial arts and GAISF is the Global Association of International Founded in 1967, GAISF is a key pillar of the combat sports Sports Federations, an umbrella body composed wider sports movement and acts as the voice of autonomous and independent International for its 125 Members, Associate Members and Sports Federations, and other international sport observers, which include both Olympic and non- and event related organisations. Olympic sports organisations. THE BENEFITS OF THE NUMBERS OF HOSTING THE WORLD THE GAMES GAISF MULTISPORT GAMES COMBAT GAMES Up to Since 2010, GAISF has successfully delivered GAISF serves as the conduit between ■ Bring sport to life in your city multisport games for combat sports and martial International Sports Federations and host cities, ■ Provide worldwide multi-channel media exposure 35 disciplines arts, mind games and urban orientated sports. bringing benefits to both with a series of right- ■ Feature the world’s best athletes sized events that best consider the needs and ■ Establish a perfect bridge between elite sport and Approximately resources of all involved. -

1St Degree Combat Maneuvers

1st Degree Combat provoked, you expend one piece of ammunition or thrown weapon. Maneuvers Doubleshot (1 point) Adamant Mountain Bonus Action—The next ranged weapon attack you make uses two missiles instead of Heavy Combat Stance (1 point) one. You make this attack with minor disadvantage. On a hit, you deal an Stance—On each of your turns, you gain additional damage die. minor advantage on your first melee weapon attack roll using a weapon with the Heavy property. Farshot Combat Stance (1 point) Stance—When you are wielding a ranged Heavy Swing (1 point) weapon, increase its normal range by 10 feet and long range by 30 feet. Reaction—When you hit with a melee weapon attack using a weapon with the Heavy property, you can use your reaction to Guarded Draw (1 point) make an additional melee weapon attack Bonus Action—Being within 5 feet of a against a second creature that is also within hostile creature who can see you and who your reach. You have minor disadvantage on isn’t incapacitated does not give you this additional attack. disadvantage when making a ranged weapon attack. In addition, when an adjacent hostile Lean Into It (1 point) creature that you can see moves 5 feet or more away from you, you can use your Technique—Until the start of your next turn, reaction to make a ranged weapon attack you deal an extra 1d4 damage whenever you against it. hit with a weapon attack using a weapon that has the Heavy property. Mirror's Glint Mountain’s Might (2 points) Intuitive Combat Stance (1 point) Bonus Action—You regain hit points equal to 1d6 + your proficiency bonus + your Stance—You gain minor advantage on Constitution modifier (minimum 0). -

Hand to Hand Combat

*FM 21-150 i FM 21-150 ii FM 21-150 iii FM 21-150 Preface This field manual contains information and guidance pertaining to rifle-bayonet fighting and hand-to-hand combat. The hand-to-hand combat portion of this manual is divided into basic and advanced training. The techniques are applied as intuitive patterns of natural movement but are initially studied according to range. Therefore, the basic principles for fighting in each range are discussed. However, for ease of learning they are studied in reverse order as they would be encountered in a combat engagement. This manual serves as a guide for instructors, trainers, and soldiers in the art of instinctive rifle-bayonet fighting. The proponent for this publication is the United States Army Infantry School. Comments and recommendations must be submitted on DA Form 2028 (Recommended Changes to Publications and Blank Forms) directly to Commandant, United States Army Infantry School, ATTN: ATSH-RB, Fort Benning, GA, 31905-5430. Unless this publication states otherwise, masculine nouns and pronouns do not refer exclusively to men. iv CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Hand-to-hand combat is an engagement between two or more persons in an empty-handed struggle or with handheld weapons such as knives, sticks, and rifles with bayonets. These fighting arts are essential military skills. Projectile weapons may be lost or broken, or they may fail to fire. When friendly and enemy forces become so intermingled that firearms and grenades are not practical, hand-to-hand combat skills become vital assets. 1-1. PURPOSE OF COMBATIVES TRAINING Today’s battlefield scenarios may require silent elimination of the enemy. -

Your Guide to a Lifetime Of

YOUR GUIDE TO A LIFETIME OF ENJOYING & IMPROVING YOUR BRAZILIAN JIU-JITSU By Five-Time World Champion Bernardo Faria Your Guide To A Lifetime Of Enjoying & Improving Your Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Table Of Contents Introduction .........................................................................................................3 Where to train? How to pick a school…? .......................................................4 How to identify a good instructor? ..................................................................4 Beginners: Which positions should you focus on? ......................................5 Tournaments help you to improve ..................................................................6 How to maximize your learning.......................................................................7 How to set up a game plan ................................................................................8 How to pick who you are going to train with ................................................9 How to deal with the frustration when you feel you are not learning ...10 How often should you train? ........................................................................... 11 How to avoid injuries .........................................................................................12 How to get a sponsor ........................................................................................13 How to work out off the mat ...........................................................................14 In BJJ there is no right or -

The Use of Functional Training – Crossfit Methods to Improve the Level of Special Training of Athletes Who Specialize in Combat Sambo

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Siberian Federal University Digital Repository The use of functional training – crossfit methods to improve the level of special training of athletes who specialize in combat sambo. ALEKSANDER OSIPOV1, 2, MIKHAIL KUDRYAVTSEV1, 3,4,5, KONSTANTIN GATILOV1, TATYANA ZHAVNER1,4, YULYA KLIMUK1, EKATERINA PONOMAREVA1, ANNA VAPAEVA1, POLINA FEDOROVA1, EVGENY GAPPEL4, ALEKSANDER KARNAUKHOV4 1Siberian Federal University, 2Krasnoyarsk State Medical University named after professor V.F. Voyno- Yasenetsky, 3Reshetnev Siberian State University of Science and Technology, 4Krasnoyarsk State Pedagogical University named after V. P. Astafiev, 5Siberian Law Institute of the Ministry of Internal Affair of Russia, Krasnoyarsk, RUSSIA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The article is devoted to the search for effective methods of training effects on athletes specializing in combat sambo. It was revealed that the main criterion determining the success of combat sambo wrestlers in the competitive activity will be the level of their special training. Moreover, this training includes special endurance of athletes, active dynamics of competitive contests and the speed of recovery of fighters after intense training and competitive loads. Besides, to increase the level of special endurance combat sambo wrestlers significantly it was suggested to include in the training process of combat athletes the method of intensive functional training - crossfit. In a year of studies the tests on the evaluation of the level of recovery of combat athletes after a specific load showed that the athletes using the training method - crossfit in their training sessions demonstrated significantly (P <0.05) the best recovery time after the load than the wrestlers who did not use this technique. -

Intracultural and Intercultural Dynamics of Capoeira Training in Brazil Paul H

ge Intracultural and Intercultural Dynamics of Capoeira Training in Brazil Paul H. Mason Journal ǁ Global Ethnographic Publication Date ǁ 1.2013 ǁ No.1 ǁ Publisher ǁ Emic Press Global Ethnographic is an open access journal. Place of Publication ǁ Kyoto, Japan ISSN 2186-0750 © Copyright Global Ethnographic 2013 Global Ethnographic and Emic Press are initiatives of the Organization for Intra-Cultural Development (OICD). Global Ethnographic 2012 photograph by Puneet Singh (2009) 2 Paul H. Mason ge Capoeira Angola performance outside the Santo Antônio Além do Carmo, also known as the Forte da Capoeira, in Salvador da Bahia, Brazil. 3 Intracultural and Intercultural Dynamics of Capoeira Training in Brazil Paul H. Mason ABSTRACT In the port-cities of Brazil during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, a distinct form of combat- dancing emerged from the interaction of African, European and indigenous peoples. The acrobatic movements and characteristic music of this art have come to be called Capoeira. Today, the art of Capoeira has grown in popularity and groups of practitioners can be found scattered across the globe. Exploring how Capoeira practitioners invent markers of difference between separate groups, the first section of this article discusses musical markers of identity that reinforce in-group and out- group dynamics. At a separate but interconnected level of analysis, the second section investigates the global origins of Capoeira movement and disambiguates the commonly recounted origin myths promoted by teachers and scholars of this art. Practitioners frequently relate stories promoting the African origins of Capoeira. However, these stories obfuscate the global origins of Capoeira music and movement and conceal the various contributions to this vibrant and eclectic form of cultural ex- pression. -

Dancing Through Difficulties: Capoeira As a Fight Against Oppression by Sara Da Conceição

Dancing Through Difficulties: Capoeira as a Fight Against Oppression by Sara da Conceição Capoeira is difficult to define. It is an African form of physical, spiritual, and cultural expression. It is an Afro-Brazilian martial art. It is a dance, a fight, a game, an art form, a mentality, an identity, a sport, an African ritual, a worldview, a weapon, and a way of life, among other things. Sometimes it is all of these things at once, sometimes it isn’t. It can be just a few of them or something different altogether. Capoeira is considered a “game” not a “fight” or a “match,” and the participants “play” rather than “fight” against each other. There are no winners or losers. It is dynamic and fluid: there is no true beginning or end to the game of capoeira. In perhaps the most widely recognized and referenced book dealing with capoeira, Ring of Liberation: Deceptive Discourse in Brazilian Capoeira, J. Lowell Lewis attempts to orient the reader with a fact-based, straightforward description of this blurred cultural genre: A game or sport played throughout Brazil (and elsewhere in the world) today, which was originally part of the Afro-Brazilian folk tradition. It is a martial art, involving a complete system of self-defense, but it also has a dance-like, acrobatic movement style which, combined with the presence of music and song, makes the games into a kind of performance that attracts many kinds of spectators, both tourists and locals. (xxiii) An outsider experiencing capoeira for the first time would undoubtedly assert that the “game” is a spectacular, impressive, and peculiar sight, due to its graceful and spontaneous integration of fighting techniques with dance, music, and unorthodox acrobatic movements. -

Mixed Martial Arts Rules for Amateur Competition Table of Contents 1

MIXED MARTIAL ARTS RULES FOR AMATEUR COMPETITION TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. SCOPE Page 2 2. VISION Page 2 3. WHAT IS THE IMMAF Page 2 4. What is the UMMAF Page 3 5. AUTHORITY Page 3 6. DEFINITIONS Page 3 7. AMATEUR STATUS Page 5 8. PROMOTERS & REQUIREMENTS Page 5 9. PROMOTERS INSURANCE Page 7 10. PHYSICIANS AND EMT’S Page 7 11. WEIGN-INS & WEIGHT DIVISIONS Page 8 12. COMPETITORS APPEARANCE& REQUIREMENTS Page 9 13. COMPETITOR’s MEDICAL TESTING Page 10 14. MATCHMAKING APPROVAL Page 11 15. BOUTS, CONTESTS & ROUNDS Page 11 16. SUSPENSIONS AND REST PERIODS Page 12 17. ADMINISTRATION & USE OF DRUGS Page 13 18. JURISDICTION,ROUNDS, STOPPING THE CONTEST Page 13 19. COMPETITOR’s REGISTRATION & EQUIPMENT Page 14 20. COMPETITON AREA Page 16 21. FOULS Page 17 22. FORBIDDEN TECHNIQUES Page 18 23. OFFICIALS Page 18 24. REFEREES Page 19 25. FOUL PROCEDURES Page 21 26. WARNINGS Page 21 27. STOPPING THE CONTEST Page 22 28. JUDGING TYPES OF CONTEST RESULTS Page 22 29. SCORING TECHNIQUES Page 23 30. CHANGE OF DECISION Page 24 31. ANNOUNCING THE RESULTS Page 24 32. PROTESTS Page 25 33. ADDENDUMS Page 26 PROTOCOL FOR COMPETITOR CORNERS ROLE OF THE INSPECTORS MEDICAL HISTORY ANNUAL PHYSICAL OPTHTHALMOLOGIC EXAM PROTOCOL FOR RINGSIDE EMERGENCY PERSONNEL PRE & POST –BOUT MEDICAL EXAM 1 SCOPE: Amateur Mixed Martial Arts [MMA] competition shall provide participants new to the sport of MMA the needed experience required in order to progress through to a possible career within the sport. The sole purpose of Amateur MMA is to provide the safest possible environment for amateur competitors to train and gain the required experience and knowledge under directed pathways allowing them to compete under the confines of the rules set out within this document. -

Bowie Mixed Martial Arts LLC 2146 PRIEST BRIDGE CT #7, CROFTON, MD 21114, UNITED STATES│ (240) 286-5219│

Free uniform included with new membership. Bowie Mixed Martial Arts LLC 2146 PRIEST BRIDGE CT #7, CROFTON, MD 21114, UNITED STATES│ (240) 286-5219│ WWW.MMAOFBOWIE.COM BOWIE MIXED MARTIAL ARTS Member Handbook BRAZILIAN JIU-JITSU │ JUDO │ WRESTLING │ KICKBOXING Copyright © 2019 Bowie Mixed Martial Arts LLC. All Rights Reserved. Bowie Mixed Martial Arts LLC 2146 PRIEST BRIDGE CT #7, CROFTON, MD 21114, UNITED STATES│ (240) 286-5219│ WWW.MMAOFBOWIE.COM Free uniform included with new membership. Member Handbook Welcome to the world of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu. The Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu program consists of a belt ranking system that begins at white belt and progresses to black belt. Each belt level consists of specific techniques in 7 major categories; takedowns, sweeps, guard passes, submissions, defenses, escapes, and combinations. Techniques begin with fundamentals and become more difficult as each level is reached. In addition, each belt level has a corresponding number of techniques for each category. The goal for each of us should be to become a Master, the epitome of the professional warrior. WARNING: Jiu-Jitsu, like any sport, involves a potential risk for serious injury. The techniques used in these classes are being demonstrated by highly trained professionals and are being shown solely for training purposes and competition. Doing techniques on your own without professional instruction and supervision is not a substitute for training. No one should attempt any of these techniques without proper personal instruction from trained instructors. Anyone who attempts any of these techniques without supervision assumes all risks. Bowie Mixed Martial Arts LLC., shall not be liable to anyone for the use of any of these techniques.