The Iconography of Patriotism George Washington and Abraham Lincoln in Union Square

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Pages from the Book

AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 2 16/3/21 18:49 What’s Mine Is Yours Private Collectors and Public Patronage in the United States Essays in Honor of Inge Reist edited by Esmée Quodbach AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 3 16/3/21 18:49 first published by This publication was organized by the Center for the History of Collecting at The Frick Collection and Center for the History of Collecting Frick Art Reference Library, New York, the Centro Frick Art Reference Library, The Frick Collection de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH), Madrid, and 1 East 70th Street the Center for Spain in America (CSA), New York. New York, NY 10021 José Luis Colomer, Director, CEEH and CSA Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica Samantha Deutch, Assistant Director, Center for Felipe IV, 12 the History of Collecting 28014 Madrid Esmée Quodbach, Editor of the Volume Margaret Laster, Manuscript Editor Center for Spain in America Isabel Morán García, Production Editor and Coordinator New York Laura Díaz Tajadura, Color Proofing Supervisor John Morris, Copyeditor © 2021 The Frick Collection, Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica, and Center for Spain in America PeiPe. Diseño y Gestión, Design and Typesetting Major support for this publication was provided by Lucam, Prepress the Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH) Brizzolis, Printing and the Center for Spain in America (CSA). Library of Congress Control Number: 2021903885 ISBN: 978-84-15245-99-5 Front cover image: Charles Willson Peale DL: M-5680-2021 (1741–1827), The Artist in His Museum. 1822. Oil on canvas, 263.5 × 202.9 cm. -

William Penn's Chair and George

WILLIAM PENN’S CHAIR AND GEORGE WASHINGTON’S HAIR: THE POLITICAL AND COMMERCIAL MEANINGS OF OBJECTS AT THE PHILADELPHIA GREAT CENTRAL FAIR, 1864 by Justina Catherine Barrett A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Early American Culture Spring 2005 Copyright 2005 Justina Catherine Barrett All rights reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1426010 Copyright 2005 by Barrett, Justina Catherine All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 1426010 Copyright 2005 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. WILLIAM PENN’S CHAIR AND GEORGE WASHINGTON’S HAIR: THE POLITICAL AND COMMERCIAL MEANINGS OF OBJECTS AT THE PHILADELPHIA GREAT CENTRAL FAIR, 1864 By Justina Catherine Barrett Approved: _______ Pauline K. Eversmann, M. Phil. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: J. -

United We Serve Relief Efforts of the Women of New York City During the Civil War

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 6-1963 United We Serve Relief Efforts of the Women of New York City During the Civil War Phyllis Korzilius Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Korzilius, Phyllis, "United We Serve Relief Efforts of the Women of New York City During the Civil War" (1963). Master's Theses. 3813. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3813 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNITED vlE SERVE Relief Efforts of the Women of New York City During the Civil War by Phyllis Korzilius A thesis presented to the ,1 •Faculty of the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Arts Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June, 1963 PREFACE In high school and college most of my study in the Civil War period centered in the great battles, generals, political figures, and national events that marked the American scene between 1861 and 1865. Because the courses were of a broad survey type, it would have been presumptuous to expect any special attention to such is sues as the role of women in the war. However, a probe of the more common or personal aspects of the "era of conflict" provides a deeper insight of the era as well as more knowledge. -

Board of Commissioners

BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS ANDREW H. GREEN, THOMAS C. FIELDS, ROBERT J. DILLON, PETER B. SWEENY, Resigned, November, 1871. HENRY HILTON, (L 22d (I tL HENRY G. STEBBINS, Appointed 22d " L ( FREDERICK E. CHURCH, L (6 61 << ANDREW H. GREEN, ROBERT J. DILLON, THOMAS C. FIELDS, FREDERICK E. CHURCH, , HENRY G. STEBBINS, . Resigned, 28th May, 1872. FRED. LAW OLMSTED, . Appointed, " LL I( President. PETER B. SWEENY, . To 22d November, 1871. LL I1 HENRY G. STEBBINS, . From " Vice-President. HENRY HILTON, . To 22d November, 1871. (Vacancy.) From " L L LC Treasurer. HENRY HILTON, . To 22d November, 1871. LC I L HENRY G. STEBBINS, . From " Conzptroller of Accounts. GE0RG.E M. VAN NORT. President and Treasurer. HENRY G. STEBBINS, . To 28th May, 1872. Il FRED. LAW OLMSTED, . From " " Vice-President. ANDREW H. GREEN, . From 15th May, 1872. Clerk to the Board. E. P. BARKER, . From 30th January to 26th June. 1 F. W. WHITTEMORE, . From 26th June to 10th July. \, I Secretary. I F. W. WHITTEMORE, . Office constituted 10th July, 1872. 8 I CONTENTS. Change of Administration-Reduction of Force-Contraction of Fields of Labor-Liabilities, November, 1871-Involved Accounts-Funds raised for one class of work applied to another- Plans Suspended-Location of Buildings for orMetropolitan Museum of Art and American Mn- seum of Natural History. ............................................................. PAt Union Spuare-Modification of its Plan-Statistics of Use-Projected Improvements.. ........ PAGE 4 111.-THE CENTRALPARK : Its Cost-Indications of its Value-the Increased Value of Real Estate-Statement of Valuations of Real Estate adjoining the Park for a series of years-The Rate of Taxes for 1871. -

The New-York Historical Society Library Department of Prints, Photographs, and Architectural Collections

Guide to the Geographic File ca 1800-present (Bulk 1850-1950) PR20 The New-York Historical Society 170 Central Park West New York, NY 10024 Descriptive Summary Title: Geographic File Dates: ca 1800-present (bulk 1850-1950) Abstract: The Geographic File includes prints, photographs, and newspaper clippings of street views and buildings in the five boroughs (Series III and IV), arranged by location or by type of structure. Series I and II contain foreign views and United States views outside of New York City. Quantity: 135 linear feet (160 boxes; 124 drawers of flat files) Call Phrase: PR 20 Note: This is a PDF version of a legacy finding aid that has not been updated recently and is provided “as is.” It is key-word searchable and can be used to identify and request materials through our online request system (AEON). PR 000 2 The New-York Historical Society Library Department of Prints, Photographs, and Architectural Collections PR 020 GEOGRAPHIC FILE Series I. Foreign Views Series II. American Views Series III. New York City Views (Manhattan) Series IV. New York City Views (Other Boroughs) Processed by Committee Current as of May 25, 2006 PR 020 3 Provenance Material is a combination of gifts and purchases. Individual dates or information can be found on the verso of most items. Access The collection is open to qualified researchers. Portions of the collection that have been photocopied or microfilmed will be brought to the researcher in that format; microfilm can be made available through Interlibrary Loan. Photocopying Photocopying will be undertaken by staff only, and is limited to twenty exposures of stable, unbound material per day. -

Volume 27 , Number 2

THE HUDSON RIVER VALLEY REVIEW A Journal of Regional Studies The Hudson River Valley Institute at Marist College is supported by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Publisher Thomas S. Wermuth, Vice President for Academic Affairs, Marist College Editors Christopher Pryslopski, Program Director, Hudson River Valley Institute, Marist College Reed Sparling, Writer, Scenic Hudson Mark James Morreale, Guest Editor Editorial Board The Hudson River Valley Review Myra Young Armstead, Professor of History, (ISSN 1546-3486) is published twice Bard College a year by the Hudson River Valley Institute at Marist College. COL Lance Betros, Professor and Head, Department of History, U.S. Military James M. Johnson, Executive Director Academy at West Point Research Assistants Kim Bridgford, Professor of English, Gabrielle Albino West Chester University Poetry Center Gail Goldsmith and Conference Amy Jacaruso Michael Groth, Professor of History, Wells College Brian Rees Susan Ingalls Lewis, Associate Professor of History, State University of New York at New Paltz Hudson River Valley Institute Advisory Board Sarah Olson, Superintendent, Roosevelt- Peter Bienstock, Chair Vanderbilt National Historic Sites Margaret R. Brinckerhoff Roger Panetta, Professor of History, Dr. Frank Bumpus Fordham University Frank J. Doherty H. Daniel Peck, Professor of English, BG (Ret) Patrick J. Garvey Vassar College Shirley M. Handel Robyn L. Rosen, Associate Professor of History, Marjorie Hart Marist College Maureen Kangas Barnabas McHenry David Schuyler, -

Fair Housing Initiatives Program Fiscal Year 2012

41436 Federal Register / Vol. 77, No. 135 / Friday, July 13, 2012 / Notices TABLE 2—ESTIMATES OF APPLICATION AND REPORTING BURDEN FOR YEAR 2—Continued Burden/ Application element Number of Responses/ response Total burden respondents respondents (hours) Table 5 ...................................................................................................... 15 1 4 60 Reporting Subtotal ............................................................................. 60 ........................ ........................ 24,259 Total ........................................................................................... 119 ........................ ........................ 25,219 The total annualized burden for the announcement lists the names and the Fair Housing Act and substantially application and reporting is 37,429 addresses of those award recipients equivalent State and local fair housing hours (49,639 + 25,219 = 74,858/2 years selected for funding based on the rating laws. Implementing regulations are = 37,429). and ranking of all applications and the found at 24 CFR part 125. Link for the application: amount of the awards. The Department published its Fair www.samhsa.gov/grants/blockgrant. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Housing Initiatives Program (FHIP) Send written comments to Summer Myron Newry, Director, FHIP Division, NOFA on February 16, 2012 announcing King, SAMHSA Reports Clearance Office of Programs, Office of Fair the availability of approximately Officer, Room 2–1057, One Choke Housing and Equal Opportunity, $42,500,000 out of the Department’s FY Cherry Road, Rockville, MD 20857 OR Department of Housing and Urban 2012 appropriation, to be utilized for email a copy to Development, 451 Seventh Street SW., FHIP projects and activities. Funding [email protected]. All Room 5230, Washington, DC 20410. availability for discretionary grants written comments should be received Telephone number 202–402–7095 (this included: the Private Enforcement within 60 days of the published date of is not a toll-free number). -

C:\Virginia's Veranda\Doll Article\Article.Wpd

The following article is copyrighted © 2007 by Virginia Mescher. It may not be copied, distributed, or reproduced in any fashion, neither in print, electronically, or any other medium, regardless of whether for fee or gratis, without the written permission of the author. “SMALL BUT MIGHTY HOST” BENEFIT AND FUND RAISING DOLLS IN THE CIVIL WAR Virginia Mescher “The doll is one of the most imperious necessities, and at the same time one of the most charming instincts of female childhood. To care for, to clothe, to adorn, to dress, to undress, to dress over again, to teach, to scold a little, to rock the cradle, to put to sleep, imagine that something is somebody—all the future of woman is there. Even when musing and prattling, when making little wardrobes and little baby clothes, while sewing little dresses, little bodices, and little jackets, the child becomes a little girl, the little girl becomes a great girl, the great girl becomes a woman. The first baby takes the place of the last doll.”—Victor Hugo Les Miserables “Leaves from Little Daughter’s Life,” April 1861, Harper’s New Monthly We often read about how funds were raised in the civil war. Taxes were levied; branches of the United States Sanitary Commission (established in 1861) held fairs in many northern cities, north and south, individual people donated both money and supplies to their respective causes, women gave of their time for sewing, knitting, making comfort bags, writing letters, and numerous other “comforts from home” for their soldiers and children knitted, wrote letters, set up fairs, and sent their pennies. -

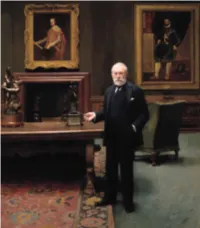

A Digital Recreation of the Lenox Library Picture Gallery: Scholarly

Sally Webster A Digital Recreation of the Lenox Library Picture Gallery: Scholarly Essay,” in Webster and Schwittek et al., “A Digital Recreation of the Lenox Library Picture Gallery: A Contribution to the Early History of Public Art Museums in the United States: Scholarly Essay Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 17, no. 2 (Autumn 2018) Citation: Sally Webster, “A Digital Recreation of the Lenox Library Picture Gallery: Scholarly Essay,” in Webster and Schwittek et al., “A Digital Recreation of the Lenox Library Picture Gallery: A Contribution to the Early History of Public Art Museums in the United States,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 17, no. 2 (Autumn 2018), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw. 2018.17.2.22. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License Creative Commons License. Webster: A Digital Recreation of the Lenox Library Picture Gallery: Scholarly Essay Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 17, no. 2 (Autumn 2018) A Digital Recreation of the Lenox Library Picture Gallery: Scholarly Essay by Sally Webster Introduction | Scholarly Essay and 3D model | Project Narrative | Appendices Click here to view: the 3D model In the archives of the New York Public Library (NYPL) is a set of nine previously unpublished installation photographs of the Lenox Library Picture Gallery (LLPG; 1882; Appendix 4), [1] which once formed an integral part of the Lenox Library located on Fifth Avenue between Seventieth and Seventy-First Streets (fig. -

Annual Update Key Fair Housing Cases

RELMAN, DANE & COLFAX WASHINGTON, DC, (202) 728-1888 Annual Update: Key Fair Housing Cases (June 2017—June 2018) National Fair Housing Alliance Annual Meeting Baltimore, Maryland – June 10, 2018 © Robert G. Schwemm Michael G. Allen Robert G. Schwemm Diane Houk Relman, Dane & Colfax PLLC Ashland-Spears Professor Emery Celli Brinckerhoff & Abady 1225 19th Street, NW, Suite 600 College of Law 600 5th Avenue at Rockefeller Center, 10th Floor Washington, DC 20036-2456 University of Kentucky New York, NY 10020-2302 (202) 728-1888 tel Lexington, KY 40506-0048 (212) 763-5000 tel (202) 728- 0848 fax (859) 257-6013 tel [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 1 RELMAN, DANE & COLFAX WASHINGTON, DC, (202) 728-1888 I. Introduction and Overview 2 Introduction and Overview A. The Federal Fair Housing Act: Basic Coverage 1. Properties 2. Transactions 3. Bases of Discrimination B. Standards of Proof: ("Because of race" and Others) C. Procedures and Relief RELMAN, DANE & COLFAX 3 WASHINGTON, DC, (202) 728-1888 Introduction and Overview D. Potential Amendments to the Fair Housing Act and Related Legislative Activity E. Importance of Other Laws: Federal, State, and Local [see also VII-A-2 and -3] F. Deference to HUD Interpretations of the FHA . Sanders v. SWS Hilltop, LLC . Simmons v. T.M. Associates Management, Inc. West v. DJ Mortgage, LLC RELMAN, DANE & COLFAX 4 WASHINGTON, DC, (202) 728-1888 Introduction and Overview G. Note on the Current Supreme Court in Civil Rights Cases RELMAN, DANE & COLFAX 5 WASHINGTON, DC, (202) 728-1888 RELMAN, DANE & COLFAX WASHINGTON, DC, (202) 728-1888 II. -

Nhtf Supporters

NHTF SUPPORTERS The National Housing Trust Fund was signed into law and continues to be a key goal on our policy agenda thanks to the incredible and ongoing support of the more than 7,000 national, state, and local supporters of the National Housing Trust Fund Campaign. NATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS AFL-CIO Housing Investment Trust African American Women's Clergy Association AIDS Action Alliance for Children and Families Alliance for Healthy Homes Alliance for Retired Americans American Association of People with Disabilities American Baptist Churches U.S.A American Congress of Community Support and Employment Services (ACCSES) American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) American Friends Service Committee American Institute of Architects American Muslim Council American Planning Association American Seniors Housing Association Americans for Democratic Action, Inc. America's Health Together The Arc of the United States ASPIRA Association, Inc. AVODAH: The Jewish Service Corps The Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law Bread for the World Call to Renewal Campaign for Migrant Domestic Workers Rights Catholic Health Association Center for Community Change Center for Women Policy Studies Central Conference of American Rabbis Child Welfare League of America Children's Defense Fund Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) in the U.S. and Canada Clean Water Action Coalition for Nonprofit Housing and Economic Development Coalition on Human Needs The Community Builders, Inc. Consortium for Citizens with Disabilities Housing Task -

FY 2012 GRANTEE LIST As of 8/8/12

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity Fair Housing Initiatives Program (FHIP) FY 2012 GRANTEE LIST as of 8/8/12 AL: ALABAMA CA: CALIFORNIA Central Alabama Fair Housing Center Bay Area Legal Aid Faith Cooper Jaclyn Pinero 1817 West Second Street 1735 Telegraph Avenue Montgomery, AL 36106-2614 Oakland, CA 94612 334-263-4663 ext. 4 510-663-4755 [email protected] [email protected] Fair Housing Center of Northern Alabama California Rural Legal Assistance, Inc. Lila Hackett Austa Wakily 1728 3rd Avenue, North, 400 C 631 Howard Street, Suite. 300 Birmingham, AL 35203-2030 San Francisco, CA 94105-3935 205-324-0111 530-742-0694 [email protected] [email protected] Mobile Fair Housing Center, Inc Fair Housing Council of Central California Teresa Bettis Marilyn Borelli PO Box 161202 560 E.Shields Avenue Mobile, AL 36616-2202 Fresno, CA 93704-2654 251-479-1532 599-244-2950 [email protected] [email protected] AZ: ARIZONA Fair Housing Council of Riverside County, Inc. Arizona Fair Housing Center Rose Mayes Edward Valenzuela 3933 Mission Inn Ave 615 N. 5th Avenue Riverside, CA 92501 Phoenix AZ 85003-1528 951- 682-6581 602-548-1599 [email protected] [email protected] or [email protected] Fair Housing of Marin Southwest Fair Housing Council Nancy Kenyon Richard Rhey 615 B St # 1 2030 E Broadway San Rafael, CA 94901 Tucson, AZ 85719 415 457-5025 520-798-1568 [email protected] [email protected] Greater Bakersfield Legal Assistance, Inc. Southern California Housing Rights Center (GBLA) Chancela Al-Mansour Estela Casas 520 South Virgil Avenue, Suite 400 615 California Avenue Los Angeles, CA 90020-1405 Bakersfield, CA 93304 213-387-8400 Ext.