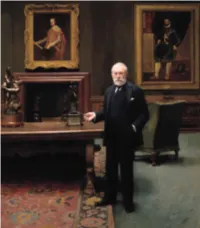

A Digital Recreation of the Lenox Library Picture Gallery: Scholarly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shearer West Phd Thesis Vol 1

THE THEATRICAL PORTRAIT IN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY LONDON (VOL. I) Shearer West A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St. Andrews 1986 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/2982 This item is protected by original copyright THE THEATRICAL PORTRAIT IN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY LONDON Ph.D. Thesis St. Andrews University Shearer West VOLUME 1 TEXT In submitting this thesis to the University of St. Andrews I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. I also understand that the title and abstract will be published, and that a copy of the I work may be made and supplied to any bona fide library or research worker. ABSTRACT A theatrical portrait is an image of an actor or actors in character. This genre was widespread in eighteenth century London and was practised by a large number of painters and engravers of all levels of ability. The sources of the genre lay in a number of diverse styles of art, including the court portraits of Lely and Kneller and the fetes galantes of Watteau and Mercier. Three types of media for theatrical portraits were particularly prevalent in London, between ca745 and 1800 : painting, print and book illustration. -

The Rhinehart Collection Rhinehart The

The The Rhinehart Collection Spine width: 0.297 inches Adjust as needed The Rhinehart Collection at appalachian state university at appalachian state university appalachian state at An Annotated Bibliography Volume II John higby Vol. II boone, north carolina John John h igby The Rhinehart Collection i Bill and Maureen Rhinehart in their library at home. ii The Rhinehart Collection at appalachian state university An Annotated Bibliography Volume II John Higby Carol Grotnes Belk Library Appalachian State University Boone, North Carolina 2011 iii International Standard Book Number: 0-000-00000-0 Library of Congress Catalog Number: 0-00000 Carol Grotnes Belk Library, Appalachian State University, Boone, North Carolina 28608 © 2011 by Appalachian State University. All rights reserved. First Edition published 2011 Designed and typeset by Ed Gaither, Office of Printing and Publications. The text face and ornaments are Adobe Caslon, a revival by designer Carol Twombly of typefaces created by English printer William Caslon in the 18th century. The decorative initials are Zallman Caps. The paper is Carnival Smooth from Smart Papers. It is of archival quality, acid-free and pH neutral. printed in the united states of america iv Foreword he books annotated in this catalogue might be regarded as forming an entity called Rhinehart II, a further gift of material embodying British T history, literature, and culture that the Rhineharts have chosen to add to the collection already sheltered in Belk Library. The books of present concern, diverse in their -

Some Pages from the Book

AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 2 16/3/21 18:49 What’s Mine Is Yours Private Collectors and Public Patronage in the United States Essays in Honor of Inge Reist edited by Esmée Quodbach AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 3 16/3/21 18:49 first published by This publication was organized by the Center for the History of Collecting at The Frick Collection and Center for the History of Collecting Frick Art Reference Library, New York, the Centro Frick Art Reference Library, The Frick Collection de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH), Madrid, and 1 East 70th Street the Center for Spain in America (CSA), New York. New York, NY 10021 José Luis Colomer, Director, CEEH and CSA Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica Samantha Deutch, Assistant Director, Center for Felipe IV, 12 the History of Collecting 28014 Madrid Esmée Quodbach, Editor of the Volume Margaret Laster, Manuscript Editor Center for Spain in America Isabel Morán García, Production Editor and Coordinator New York Laura Díaz Tajadura, Color Proofing Supervisor John Morris, Copyeditor © 2021 The Frick Collection, Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica, and Center for Spain in America PeiPe. Diseño y Gestión, Design and Typesetting Major support for this publication was provided by Lucam, Prepress the Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH) Brizzolis, Printing and the Center for Spain in America (CSA). Library of Congress Control Number: 2021903885 ISBN: 978-84-15245-99-5 Front cover image: Charles Willson Peale DL: M-5680-2021 (1741–1827), The Artist in His Museum. 1822. Oil on canvas, 263.5 × 202.9 cm. -

William Penn's Chair and George

WILLIAM PENN’S CHAIR AND GEORGE WASHINGTON’S HAIR: THE POLITICAL AND COMMERCIAL MEANINGS OF OBJECTS AT THE PHILADELPHIA GREAT CENTRAL FAIR, 1864 by Justina Catherine Barrett A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Early American Culture Spring 2005 Copyright 2005 Justina Catherine Barrett All rights reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1426010 Copyright 2005 by Barrett, Justina Catherine All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 1426010 Copyright 2005 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. WILLIAM PENN’S CHAIR AND GEORGE WASHINGTON’S HAIR: THE POLITICAL AND COMMERCIAL MEANINGS OF OBJECTS AT THE PHILADELPHIA GREAT CENTRAL FAIR, 1864 By Justina Catherine Barrett Approved: _______ Pauline K. Eversmann, M. Phil. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: J. -

MH-00-19-0031-19 the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

Museum Grants for African American History and Culture Sample Application MH-00-19-0031-19 “Schomburg Curriculum Project” The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture New York, NY Amount awarded by IMLS: $133,912 Amount of cost share: $133,912 Attached are the following components excerpted from the original application. Abstract . Narrative . Schedule of Completion Please note that the instructions for preparing applications for the FY2020 Museum Grants for African American History and Culture grant program differ from those that guided the preparation of FY2019 applications. Be sure to use the instructions in the FY2020 Notice of Funding Opportunity for the grant program to which you are applying. Museum Grants for African American History and Culture Program The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture Abstract There is a growing demand nationwide for culturally relevant curricula in the nation’s K-12 classrooms. In New York, the State Education Department plans to mandate that all schools implement culturally relevant pedagogical methods, including the use of curricula that draw on a broader array of social experiences, while nationally a recent report by the Southern Poverty Law Center demonstrated both that students are under-educated about the history of slavery and that teachers recognize that they have not been well-prepared to teach it. With its rich collections of more than 11 million items and its strong relationships with local educators, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, a research unit of The New York Public Library, is uniquely poised to meet these needs. Through the proposed Schomburg Curriculum Project, the Schomburg Center will engage a consultant Curriculum Writer to develop a history curriculum for grades 6-12 focusing on key themes in African American history that can be illustrated using the Schomburg Center’s rich collections. -

MXB Virtual Tour

Projects & Proposals > Manhattan > Virtual Tour of Malcolm X Boulevard Archived Content This page describes Malcolm X Boulevard as it appeared in 2001. The tour was developed as part of the Malcolm X Boulevard Streetscape Enhancement Project. Welcome! Welcome to Malcolm X Boulevard in the heart of Harlem! This online virtual tour highlights the landmarks of Harlem and is available in printable text form. Introduction: This tour was developed by the Department of City Planning as part of its Malcolm X Boulevard Streetscape Enhancement Project. The project, which extends from West 110th to West 147th Street, seeks to complement the ongoing capital improvements for Malcolm X Boulevard and take advantage of the growing tourist interest in Harlem. The project proposes a program of streetscape and pedestrian space improvements, including new pedestrian lighting, new sidewalk and median landscaping and the provision of pedestrian amenities, such as seating and pergolas. The Department has been working with Cityscape Institute, the Upper Manhattan Empowerment Zone, the New York City Department of Transportation, and the Department of Design and Construction, and has received implementation funds totaling $1.2 million through the federal TEA21 Enhancement Funding program for the proposed pedestrian lighting improvements. As one element of the project, the Department developed this guided tour of the boulevard and neighboring blocks. The tour provides an overview of local area history, and highlights architecturally significant and landmarked buildings, noteworthy cultural and ecclesiastical institutions and other points of interest. A listing of former famous jazz clubs, such as the Cotton Club and Savoy Ballroom, is also provided. Envisioned as an information resource for residents and visitors, the tour is also available in printable text format for use as a hand-held guide for a self-guided walking tour along the boulevard. -

United We Serve Relief Efforts of the Women of New York City During the Civil War

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 6-1963 United We Serve Relief Efforts of the Women of New York City During the Civil War Phyllis Korzilius Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Korzilius, Phyllis, "United We Serve Relief Efforts of the Women of New York City During the Civil War" (1963). Master's Theses. 3813. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3813 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNITED vlE SERVE Relief Efforts of the Women of New York City During the Civil War by Phyllis Korzilius A thesis presented to the ,1 •Faculty of the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Arts Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June, 1963 PREFACE In high school and college most of my study in the Civil War period centered in the great battles, generals, political figures, and national events that marked the American scene between 1861 and 1865. Because the courses were of a broad survey type, it would have been presumptuous to expect any special attention to such is sues as the role of women in the war. However, a probe of the more common or personal aspects of the "era of conflict" provides a deeper insight of the era as well as more knowledge. -

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in the Corcoran Gallery of Art

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art VOLUME I THE CORCORAN GALLERY OF ART WASHINGTON, D.C. A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art Volume 1 PAINTERS BORN BEFORE 1850 THE CORCORAN GALLERY OF ART WASHINGTON, D.C Copyright © 1966 By The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 20006 The Board of Trustees of The Corcoran Gallery of Art George E. Hamilton, Jr., President Robert V. Fleming Charles C. Glover, Jr. Corcoran Thorn, Jr. Katherine Morris Hall Frederick M. Bradley David E. Finley Gordon Gray David Lloyd Kreeger William Wilson Corcoran 69.1 A cknowledgments While the need for a catalogue of the collection has been apparent for some time, the preparation of this publication did not actually begin until June, 1965. Since that time a great many individuals and institutions have assisted in com- pleting the information contained herein. It is impossible to mention each indi- vidual and institution who has contributed to this project. But we take particular pleasure in recording our indebtedness to the staffs of the following institutions for their invaluable assistance: The Frick Art Reference Library, The District of Columbia Public Library, The Library of the National Gallery of Art, The Prints and Photographs Division, The Library of Congress. For assistance with particular research problems, and in compiling biographi- cal information on many of the artists included in this volume, special thanks are due to Mrs. Philip W. Amram, Miss Nancy Berman, Mrs. Christopher Bever, Mrs. Carter Burns, Professor Francis W. -

New York Public Library and the Proposed Designation of the Related Landmark Site

LA.NDJVL.\.RKS PRESERVATION CCNMISSION Jan~~ry 11, 1967, Number 5 LP-0246 NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRi;RY, 476 Fifth :venue at 42nd Street, Borough of Manhattan. Begun 1898, completed 1911; architects Carrere & Hastings. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1257, Lot 1. On April 12, 1966, the Landmarks Pre serv~tion Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the New York Public Library and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site. (Item No. 28). Two witnesses spoke in favor of designation. The Commission continued the public hearing until June 14, 1966. (Item No. 1). At that time one sepaker favored designation. Both hearings Here duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. There were no spe~kers in opposition to designation at either meeting. In a l etter to the Commission, the Director of the Library approved desig~~tion. DESCRIPTION .ruiD JUJALYSIS The Central Building of the New York Public Library occupies a fabulous site, that has often been r eferred to as "the crossroads of the worldlf. This majestic marble building, one of the masterpieces of the Beaux-Arts style of architecture, is a magnificent civic monument and fully justifies the pride of its generation and of ours. It sits regally enthroned on a terraced plateau, displaying ur~s, fountains, flagpoles, sculpture and ornan1ent. Replete with sparkle and delicacy, it is by night or day a, :joyous creation. This building comes closer than any other in America to tho complete realization of Beaux Jwts design at its best. -

Recollections of Mr. James Lenox of New York and the Formation Of

RECOLLECTIONS OF MR JAMES LENOX OF NEW YORK AND THE FORMATION OF r HIS LIBRARY A nation's Books are her vouchers ; her Libraries are her muniments. H. S. RECOLLECTIONS OF MR JAMES LENOX OF NEW YORK AND THE FORMATION OF HIS LIBRARY By HENRY STEVENS of Vermont Bibliographer and Lover of Books Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Old England and Corresponding Member of the American Antiquarian Society of New England of the Massachusetts Historical Society and of the New England Genealo gical Society Life Member of the British Association for the Advance ment of Science Fellow of the British Archaeological Association and the Zoological Society of London Black Balled Athenaeum Club of London also Patriarch of Skull & Bones of Yale and Member of the Historical Societies of Vermont New York Wisconsin Maryland &c &c BA and MA of Yale College as well as Citizen of Noviomagus et cetera LONDON HENRY STEVENS & SON 115 ST MARTIN'S LA Over against the Church of St Martin in the Fields MDCCCLXXXVI LIBRARY SCHOOL c TO THE READER WHO faulteth not, liueth not ; who mendeth faults is commended : The Printer hath faulted a little : it may be the author oversighted more. is the least then erre not Thy paine (Reader) ; thou most by misconstruing or sharpe censuring ; least thou be more vncharitable, then either of them hath been heedlesse : God amend and guide vs a\\.Robartes on Tythes 4 Camb. 1613. COPYRIGHT l886 BY HENRY N. STEVENS FOR AULD LANG SYNE THESE pages are inscribed with plea- sant Recollections of more than forty- five years to my old and valued friend DOCTOR GEORGE H. -

Sterne and Visual Culture IO

Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions The Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If electronic transmission of reserve material is used for purposes in excess of what constitutes "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO LAURENCE STERNE EDITED BY THOMAS KEYMER • CAMBRIDGE . :;: . UNIVERSITY PRESS Sterne and visual Culture IO PETER DE VOOGD Sterne and visual culture We will never know his name, and can only guess at his motives. He was probably a sailor, who possessed a copy ofW. W. Ryland's stipple engraving (1779) after Angelica Kauffman's painting of 'Maria - Moulines', and had time on his hands. He cut out Maria's face, coloured it in, stitched it on an oval piece ofcanvas, and skilfully embroidered the rest with wool and silk: her white dress, her dog Sylvio, a brook, and a poplar tree (see Fig. 4). His 'woolwork' is unusual in that it does not depict a ship or naval scene, as is normally the case in this curious genre (woolwork being a type of woven or embroidered picture widely produced by sailors in the period, usually of their own vessels). And although this is a rare and early example, it is not the only one. -

Oconnellkarenhoffman.Pdf (565Kb)

THE LIBRARY OF JOHN GILMARY SHEA: EXPLORING THE BOOK COLLECTING MIND OF A NINETEENTH-CENTURY HISTORIAN A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies By Karen H. O’Connell, M.S.L.S. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. April 4, 2011 Copyright © 2011 by Karen H. O’Connell All Rights Reserved ii THE LIBRARY OF JOHN GILMARY SHEA: EXPLORING THE BOOK COLLECTING MIND OF A NINETEENTH-CENTURY HISTORIAN Karen H. O’Connell, M.S.L.S. Mentor: William J. O’Brien, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Since there have been books to collect, there have been book collectors. When Renaissance technology brought about the possibility for a wider distribution of books (i.e., knowledge) with the development of printing using moveable type, books became less unique; however, books remained dear for several hundred years. And beyond their tomes, book collectors have existed to varying heights of fame throughout history. Is it the books collected or the collectors themselves that should be remembered? Perhaps it is both. There have been memorable collectors from the Middle Ages through the nineteenth century, when again, technology changed and expanded the dissemination of knowledge. These include Bishop Richard de Bury, Jean Grolier, Jacques-Auguste de Thou, the Marquesa de Pompadour, Sir John Soane, Thomas Jefferson, James Lenox, and Rush C. Hawkins. John Gilmary Shea was a nineteenth-century book collector of great depth; but who today remembers him as such? Historians go in and out of favor, as historical trends change.