Oconnellkarenhoffman.Pdf (565Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JOHN W. O Malley, S.J

JESUIT SCHOOLS AND THE HUMANITIES YESTERDAY AND TODAY ashington, D.C. 20036-5727 Jesuit Conference, Inc. 1016 16th St. NW Suite 400 W SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION, EFFECTIVE JANUARY 2015 The Seminar is composed of a number of Jesuits appointed from their prov- U.S. JESUITS inces in the United States. An annual subscription is provided by the Jesuit Conference for U.S. Jesuits living in the United The Seminar studies topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and practice States and U.S. Jesuits who are still members of a U.S. Province but living outside the United of Jesuits, especially American Jesuits, and gathers current scholarly stud- States. ies pertaining to the history and ministries of Jesuits throughout the world. ALL OTHER SUBSCRIBERS It then disseminates the results through this journal. All subscriptions will be handled by the Business Offce U.S.: One year, $22; two years, $40. (Discount $2 for Website payment.) The issues treated may be common also to Jesuits of other regions, other Canada and Mexico: One year, $30; two years, $52. (Discount $2 for Website payment.) priests, religious, and laity. Hence, the studies, while meant especially for American Jesuits, are not exclusively for them. Others who may fnd them Other destinations: One year: $34; two years, $60. (Discount $2 for Website payment.) helpful are cordially welcome to read them at: [email protected]/jesuits . ORDERING AND PAYMENT Place orders at www.agrjesuits.com to receive Discount If paying by check - Make checks payable to: Seminar on Jesuit Spirituality Payment required at time of ordering and must be made in U.S. -

Spring/Summer 2021 Newsletter

Non-Profit Organization U.S. Postage Advancement Office PAID 2112 North Vermilion Street Danville, IL 61832-1798 View from the Hill is published by the Schlarman Academy Advancement Office. Please send corrections and/or address changes to Schlarman Academy Advancement Office, 2112 N. Vermilion St., Danville, IL 61832. All articles are written by staff unless otherwise noted. Articles may be edited for publication space. We also use various Internet sources for information. Letter From The Principal This was one of the most unusual years ever on record! While others were either not in session or were fully remote we tried hard to make the school year as normal as possible. There were, however, some things missing…like athletics for two thirds of the year, dances, and other special events. And I know that a lot of what we had to do to be compliant and still stay in session was not popular with many parents and students. But, we got through it! Are we better for it? Only time will tell! I am not totally sure about how emotionally ready we were for what transpired over the past year. Nor am I totally sure about how we may handle the next year or two. What I am sure about is that after participating in remote learning with all of our students for about six weeks this year, there is no substitution for in-person instruction. Our teachers deserve numerous red apples for their job this year during the remote learning phase we were forced to endure. With all of that behind us, it is time to discuss about what may lie ahead of us. -

The Field Museum 2002 Annual Report to the Board of Trustees Academic Affairs

THE FIELD MUSEUM 2002 ANNUAL REPORT TO THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES ACADEMIC AFFAIRS Office of Academic Affairs, The Field Museum 1400 South Lake Shore Drive Chicago, IL 60605-2496 USA Phone (312) 665-7811 Fax (312) 665-7806 WWW address: http://www.fieldmuseum.org - This Report Printed on Recycled Paper - -1- Revised May 2003 -2- CONTENTS 2002 Annual Report....................................................................................................................................................3 Collections and Research Committee.....................................................................................................................12 Academic Affairs Staff List......................................................................................................................................13 Publications, 2002 .....................................................................................................................................................19 Active Grants, 2002...................................................................................................................................................38 Conferences, Symposia, Workshops and Invited Lectures, 2002 .......................................................................46 Museum and Public Service, 2002 ..........................................................................................................................55 Fieldwork and Research Travel, 2002 ....................................................................................................................65 -

It's a Conspiracy

IT’S A CONSPIRACY! As a Cautionary Remembrance of the JFK Assassination—A Survey of Films With A Paranoid Edge Dan Akira Nishimura with Don Malcolm The only culture to enlist the imagination and change the charac- der. As it snows, he walks the streets of the town that will be forever ter of Americans was the one we had been given by the movies… changed. The banker Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore), a scrooge-like No movie star had the mind, courage or force to be national character, practically owns Bedford Falls. As he prepares to reshape leader… So the President nominated himself. He would fill the it in his own image, Potter doesn’t act alone. There’s also a board void. He would be the movie star come to life as President. of directors with identities shielded from the public (think MPAA). Who are these people? And what’s so wonderful about them? —Norman Mailer 3. Ace in the Hole (1951) resident John F. Kennedy was a movie fan. Ironically, one A former big city reporter of his favorites was The Manchurian Candidate (1962), lands a job for an Albu- directed by John Frankenheimer. With the president’s per- querque daily. Chuck Tatum mission, Frankenheimer was able to shoot scenes from (Kirk Douglas) is looking for Seven Days in May (1964) at the White House. Due to a ticket back to “the Apple.” Pthe events of November 1963, both films seem prescient. He thinks he’s found it when Was Lee Harvey Oswald a sleeper agent, a “Manchurian candidate?” Leo Mimosa (Richard Bene- Or was it a military coup as in the latter film? Or both? dict) is trapped in a cave Over the years, many films have dealt with political conspira- collapse. -

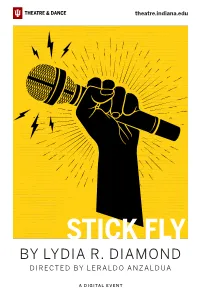

Stick Fly Program

theatre.indiana.edu STICK FLY BY LYDIA R. DIAMOND DIRECTED BY LERALDO ANZALDUA A DIGITAL EVENT IU Theatre & Dance wishes to acknowledge and honor the Miami, Delaware, Potawatomi, and Shawnee people, on whose ancestral homelands and resources PRESENTS Indiana University was built. LIVE STICK FLY PERFORMANCE by Lydia R. Diamond The mission of the Department of Theatre, Drama, and Contemporary Dance is to advance the art, scholarship, and appreciation of theatre and dance and its DIRECTOR Leraldo Anzaldua place in society. We pursue this mission collectively STAGE MANAGER Jorie Miller and as individuals through theatrical productions, scholarship and publication, presentation of our work in national and international venues, formal instruction, and individual mentoring. The Department of Theatre, Drama, and Contemporary Dance is accredited by the National Association of Schools of Theatre and is a member of the University/ Stick Fly is presented by arrangement with Concord Theatricals on behalf of Resident Theatre Association Samuel French, Inc. www.concordtheatricals.com and United States Institute for Theatre Technology. Stick Fly was developed in part at Chicago Dramatists, originally produced by Congo Square Theatre and subsequently produced by McCarter Theatre Center. A further developmental production directed by Kenny Leon, was LIVING produced jointly by Arena Stage and the Huntington Theatre Company. IMPACT The video and/or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. A DIGITAL EVENT | FEBRUARY 12–13, 2021 3 Cast Production -

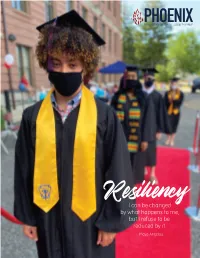

I Can Be Changed by What Happens to Me, but I Refuse to Be Reduced by It

ResiliencyI can be changed by what happens to me, but I refuse to be reduced by it. —Maya Angelou Phoenix Magazine is the voice and vision of Saint Joseph Prep Kathleen McCarvill, Co-Head of School Eugene Ward, Co-Head of School Carol Woolston, Asst. Head of School for Community Life Laura Grzbowski, Assistant Director of Advancement damian israel shiner, Creative Director Taya Latham, Communications Associate © 2020 by Saint Joseph Prep IN THIS ISSUE... 4 RESILIENCY: LEARNING IN THE TIME OF COVID The student experience as the School pivoted to Remote Learning 6 RESILIENCY: TEACHING IN THE TIME OF COVID The faculty perspective on teaching in the virtual realm 8 FROM PLAYS TO PODCASTS How the Phoenix Players recreated a classic radio drama 9 A VIRTUAL SHOWCASE The spring STEAM Show posts as an online gallery 10 FOR LOVE OF THE GAME First SJP junior commits to college athletics 11 STRONG AS IRON The five graduates awarded the Iron Phoenix 12 FINDING RESILIENCY IN SERVICE A team of students and faculty members serve in Camden, NJ 14 BLACK HISTORY MATTERS Efforts by students and faculty to educate and to eradicate racial injustice 16 (COMMENCEMENT) Honoring the Class of 2020 as they graduate 18 PLANS INTERRUPTED How an SJP grad found opportunity amid COVID 20 RESILIENCE FOR THE DEAR NEIGHBOR How the CSJs stand up against systemic violence and injustice 22 WE DID IT! The incredible fundraising campaign inspired by Agnes Burns Hughes, MSJA ’48 23 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR 24 ANNUAL REPORT OF GIFTS, 2019-2020 31 FIVE YEAR REUNION Greetings from Saint Joseph Prep! This issue of the Phoenix magazine celebrates the theme of RESILIENCY. -

The Carroll News

John Carroll University Carroll Collected The aC rroll News Student 4-30-1998 The aC rroll News- Vol. 90, No. 23 John Carroll University Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews Recommended Citation John Carroll University, "The aC rroll News- Vol. 90, No. 23" (1998). The Carroll News. 1093. http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews/1093 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aC rroll News by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. !for You . .9lbout 'You. r.By 'You. Volume 90 • Number 23 John Carroll University • Cleveland, Ohio April 30, 1998 ----~--------------------------- ---- ---·----------------- --- -- JCU A/1-Amercian JCU star signed by NFL London Fletcher Mark Boleky rai e by herself At the age of 12, cided to take up orgamzed foot Sports Editor his Sister wa brutally raped ball That year he earned all-dis headed for NFL Thosearound him have known Fletcher began spendmg more trict and all state honors for years he was too good to play time with a group of f nend > Fletcher followed a basketball here. which could probably have been cholar h1p to the D1vision I St This fact became clear to the con idered a gang. Francis (Pa), but transferred to rest of the football world last He knew he needed an outlet, Carroll after a year. "I began to Thursday, when recent John Car and sports became the easy choice. miss football, and I knew I could roll University graduate London Especially easy con idering ath transfer Ito a DIVISion Ill school! Fletcher made the rare leap from letics come JUSt about a ea y a without s1ttmg out a year," he sa1d Division IJitosigninganNFLcon breathing for fletcher. -

Glossary, Bibliography, Index of Printed Edition

GLOSSARY Bishop A member of the hierarchy of the Church, given jurisdiction over a diocese; or an archbishop over an archdiocese Bull (From bulla, a seal) A solemn pronouncement by the Pope, such as the 1537 Bull of Pope Paul III, Sublimis Deus,proclaiming the human rights of the Indians (See Ch. 1, n. 16) Chapter An assembly of members, or delegates of a community, province, congregation, or the entire Order of Preachers. A chapter is called for decision-making or election, at intervals determined by the Constitutions. Coadjutor One appointed to assist a bishop in his diocese, with the right to succeed him as its head. Bishop Congregation A title given by the Church to an approved body of religious women or men. Convent The local house of a community of Dominican friars or sisters. Council The central governing unit of a Dominican priory, province, congregation, monastery, laity and the entire Order. Diocese A division of the Church embracing the members entrusted to a bishop; in the case of an archdiocese, an archbishop. Divine Office The Liturgy of the Hours. The official prayer of the Church composed of psalms, hymns and readings from Scripture or related sources. Episcopal Related to a bishop and his jurisdiction in the Church; as in "Episcopal See." Exeat Authorization given to a priest by his bishop to serve in another diocese. Faculties Authorization given a priest by the bishop for priestly ministry in his diocese. Friar A priest or cooperator brother of the Order of Preachers. Lay Brother A term used in the past for "cooperator brother." Lay Dominican A professed member of the Dominican Laity, once called "Third Order." Mandamus The official assignment of a friar or a sister to a Communit and ministry related to the mission of the Order. -

MH-00-19-0031-19 the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

Museum Grants for African American History and Culture Sample Application MH-00-19-0031-19 “Schomburg Curriculum Project” The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture New York, NY Amount awarded by IMLS: $133,912 Amount of cost share: $133,912 Attached are the following components excerpted from the original application. Abstract . Narrative . Schedule of Completion Please note that the instructions for preparing applications for the FY2020 Museum Grants for African American History and Culture grant program differ from those that guided the preparation of FY2019 applications. Be sure to use the instructions in the FY2020 Notice of Funding Opportunity for the grant program to which you are applying. Museum Grants for African American History and Culture Program The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture Abstract There is a growing demand nationwide for culturally relevant curricula in the nation’s K-12 classrooms. In New York, the State Education Department plans to mandate that all schools implement culturally relevant pedagogical methods, including the use of curricula that draw on a broader array of social experiences, while nationally a recent report by the Southern Poverty Law Center demonstrated both that students are under-educated about the history of slavery and that teachers recognize that they have not been well-prepared to teach it. With its rich collections of more than 11 million items and its strong relationships with local educators, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, a research unit of The New York Public Library, is uniquely poised to meet these needs. Through the proposed Schomburg Curriculum Project, the Schomburg Center will engage a consultant Curriculum Writer to develop a history curriculum for grades 6-12 focusing on key themes in African American history that can be illustrated using the Schomburg Center’s rich collections. -

Guide to the John Gilmary Shea Papers

University of Dayton eCommons Guides to Archival and Special Collections University Libraries 10-3-2012 Guide to the John Gilmary Shea Papers Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/finding_aid eCommons Citation "Guide to the John Gilmary Shea Papers" (2012). Guides to Archival and Special Collections. 37. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/finding_aid/37 This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the University Libraries at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Guides to Archival and Special Collections by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Guide to the John Gilmary Shea papers, 1683-1890, bulk 1853-1890 CSC.014 Finding aid prepared by Colleen Mahoney This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit October 03, 2012 Describing Archives: A Content Standard U.S. Catholic Special Collection, Roesch Library University of Dayton 300 College Park Dayton, Ohio, 45469-1360 937-229-1347 [email protected] Guide to the John Gilmary Shea papers, 1683-1890, bulk 1853-1890 CSC.014 Table of Contents Summary Information ............................................................................................................... 3 Biography of John Gilmary Shea................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents.........................................................................................................................4 -

MXB Virtual Tour

Projects & Proposals > Manhattan > Virtual Tour of Malcolm X Boulevard Archived Content This page describes Malcolm X Boulevard as it appeared in 2001. The tour was developed as part of the Malcolm X Boulevard Streetscape Enhancement Project. Welcome! Welcome to Malcolm X Boulevard in the heart of Harlem! This online virtual tour highlights the landmarks of Harlem and is available in printable text form. Introduction: This tour was developed by the Department of City Planning as part of its Malcolm X Boulevard Streetscape Enhancement Project. The project, which extends from West 110th to West 147th Street, seeks to complement the ongoing capital improvements for Malcolm X Boulevard and take advantage of the growing tourist interest in Harlem. The project proposes a program of streetscape and pedestrian space improvements, including new pedestrian lighting, new sidewalk and median landscaping and the provision of pedestrian amenities, such as seating and pergolas. The Department has been working with Cityscape Institute, the Upper Manhattan Empowerment Zone, the New York City Department of Transportation, and the Department of Design and Construction, and has received implementation funds totaling $1.2 million through the federal TEA21 Enhancement Funding program for the proposed pedestrian lighting improvements. As one element of the project, the Department developed this guided tour of the boulevard and neighboring blocks. The tour provides an overview of local area history, and highlights architecturally significant and landmarked buildings, noteworthy cultural and ecclesiastical institutions and other points of interest. A listing of former famous jazz clubs, such as the Cotton Club and Savoy Ballroom, is also provided. Envisioned as an information resource for residents and visitors, the tour is also available in printable text format for use as a hand-held guide for a self-guided walking tour along the boulevard. -

New York Public Library and the Proposed Designation of the Related Landmark Site

LA.NDJVL.\.RKS PRESERVATION CCNMISSION Jan~~ry 11, 1967, Number 5 LP-0246 NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRi;RY, 476 Fifth :venue at 42nd Street, Borough of Manhattan. Begun 1898, completed 1911; architects Carrere & Hastings. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1257, Lot 1. On April 12, 1966, the Landmarks Pre serv~tion Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the New York Public Library and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site. (Item No. 28). Two witnesses spoke in favor of designation. The Commission continued the public hearing until June 14, 1966. (Item No. 1). At that time one sepaker favored designation. Both hearings Here duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. There were no spe~kers in opposition to designation at either meeting. In a l etter to the Commission, the Director of the Library approved desig~~tion. DESCRIPTION .ruiD JUJALYSIS The Central Building of the New York Public Library occupies a fabulous site, that has often been r eferred to as "the crossroads of the worldlf. This majestic marble building, one of the masterpieces of the Beaux-Arts style of architecture, is a magnificent civic monument and fully justifies the pride of its generation and of ours. It sits regally enthroned on a terraced plateau, displaying ur~s, fountains, flagpoles, sculpture and ornan1ent. Replete with sparkle and delicacy, it is by night or day a, :joyous creation. This building comes closer than any other in America to tho complete realization of Beaux Jwts design at its best.