Remote Islands Development Area in Kagoshima Prefecture Shunsuke NAGASHIMA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GSJ MAP G050 16002 1982 D.Pdf

目 次 Ⅰ.地 形 ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Ⅰ.1 海底地形 ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 5 Ⅰ.2 陸上地形 ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 5 Ⅱ.地質概説 …………………………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Ⅱ.1 研究史 ………………………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Ⅱ.2 地質の概略 …………………………………………………………………………………………… 8 Ⅱ.3 岩石 ……………………………………………………………………………………………………11 Ⅱ.4 地球物理 ………………………………………………………………………………………………15 Ⅱ.5 1934-35年の噴火,新硫黄島の生成 ………………………………………………………………17 Ⅲ.先カルデラ火山群 ………………………………………………………………………………………20 Ⅲ.1 玄武岩・安山岩火山群 ………………………………………………………………………………20 Ⅲ.1.1 高平山火山 ………………………………………………………………………………………20 Ⅲ.1.2 真米山火山 ………………………………………………………………………………………22 Ⅲ.1.3 矢筈山火山 ………………………………………………………………………………………23 Ⅲ.2 流紋岩・デイサイト溶岩群 …………………………………………………………………………26 Ⅲ.2.1 ヤクロ瀬溶岩 ……………………………………………………………………………………26 Ⅲ.2.2 竹島ノ鵜瀬溶岩 ……………………………………………………………………………………27 Ⅲ.2.3 長浜溶岩 …………………………………………………………………………………………28 Ⅲ.2.4 赤崎溶岩 …………………………………………………………………………………………29 Ⅲ.2.5 崎ノ江鼻溶岩 ……………………………………………………………………………………30 Ⅳ.カルデラ形成期の火砕岩類 ……………………………………………………………………………30 Ⅳ.1 小アビ山火砕流堆積物 ………………………………………………………………………………30 Ⅳ.2 長瀬火砕流堆積物 ……………………………………………………………………………………35 Ⅳ.3 籠港降下火砕物層 ……………………………………………………………………………………37 Ⅳ.4 末期噴火サイクルの噴出物 …………………………………………………………………………38 Ⅳ.4.1 船倉降下軽石 ……………………………………………………………………………………38 Ⅳ.4.2 船倉火砕流堆積物 …………………………………………………………………………………41 Ⅳ.4.3 竹島火砕流堆積物 …………………………………………………………………………………42 Ⅴ.後カルデラ火山 …………………………………………………………………………………………45 Ⅴ.1 海底中央火口丘群及び浅瀬溶岩 ……………………………………………………………………45 Ⅴ.2 稲村岳火山 ……………………………………………………………………………………………48 Ⅴ.3 硫黄岳火山 ……………………………………………………………………………………………51 Ⅴ.4 降下火山灰層 …………………………………………………………………………………………58 -

Full Download

VOLUME 1: BORDERS 2018 Published by National Institute of Japanese Literature Tokyo EDITORIAL BOARD Chief Editor IMANISHI Yūichirō Professor Emeritus of the National Institute of Japanese 今西祐一郎 Literature; Representative Researcher Editors KOBAYASHI Kenji Professor at the National Institute of Japanese Literature 小林 健二 SAITō Maori Professor at the National Institute of Japanese Literature 齋藤真麻理 UNNO Keisuke Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese 海野 圭介 Literature KOIDA Tomoko Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese 恋田 知子 Literature Didier DAVIN Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese ディディエ・ダヴァン Literature Kristopher REEVES Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese クリストファー・リーブズ Literature ADVISORY BOARD Jean-Noël ROBERT Professor at Collège de France ジャン=ノエル・ロベール X. Jie YANG Professor at University of Calgary 楊 暁捷 SHIMAZAKI Satoko Associate Professor at University of Southern California 嶋崎 聡子 Michael WATSON Professor at Meiji Gakuin University マイケル・ワトソン ARAKI Hiroshi Professor at International Research Center for Japanese 荒木 浩 Studies Center for Collaborative Research on Pre-modern Texts, National Institute of Japanese Literature (NIJL) National Institutes for the Humanities 10-3 Midori-chō, Tachikawa City, Tokyo 190-0014, Japan Telephone: 81-50-5533-2900 Fax: 81-42-526-8883 e-mail: [email protected] Website: https//www.nijl.ac.jp Copyright 2018 by National Institute of Japanese Literature, all rights reserved. PRINTED IN JAPAN KOMIYAMA PRINTING CO., TOKYO CONTENTS -

Genetic Lineage of the Amami Islanders Inferred from Classical Genetic Markers

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.18.440379; this version posted April 19, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Genetic lineage of the Amami islanders inferred from classical genetic markers Yuri Nishikawa and Takafumi Ishida Department of Biological Sciences, Graduate School of Science, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan Correspondence: Yuri Nishikawa, Department of Biological Sciences, Graduate School of Science, The University of Tokyo, Hongo 7-3-1, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan. E-mail address: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.18.440379; this version posted April 19, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract The peopling of mainland Japan and Okinawa has been gradually unveiled in the recent years, but previous anthropological studies dealing people in the Amami islands, located between mainland Japan and Okinawa, were less informative because of the lack of genetic data. In this study, we collected DNAs from 104 subjects in two of the Amami islands, Amami-Oshima island and Kikai island, and analyzed the D-loop region of mtDNA, four Y-STRs and four autosomal nonsynonymous SNPs to clarify the genetic structure of the Amami islanders comparing with peoples in Okinawa, mainland Japan and other regions in East Asia. -

Local Dishes Loved by the Nation

Sapporo 1 Hakodate 2 Japan 5 3 Niigata 6 4 Kanazawa 15 7 Sendai Kyoto 17 16 Kobe 10 9 18 20 31 11 8 ocal dishes Hiroshima 32 21 33 28 26 19 13 Fukuoka 34 25 12 35 23 22 14 40 37 27 24 29 Tokyo loved by 41 38 36 Nagoya 42 44 39 30 Shizuoka Yokohama 43 45 Osaka Nagasaki 46 Kochi the nation Kumamoto ■ Hokkaido ■ Tohoku Kagoshima L ■ Kanto ■ Chubu ■ Kansai 47 ■ Chugoku ■ Shikoku Naha ■ Kyushu ■ Okinawa 1 Hokkaido 17 Ishikawa Prefecture 33 Okayama Prefecture 2 Aomori Prefecture 18 Fukui Prefecture 34 Hiroshima Prefecture 3 Iwate Prefecture 19 Yamanashi Prefecture 35 Yamaguchi Prefecture 4 Miyagi Prefecture 20 Nagano Prefecture 36 Tokushima Prefecture 5 Akita Prefecture 21 Gifu Prefecture 37 Kagawa Prefecture 6 Yamagata Prefecture 22 Shizuoka Prefecture 38 Ehime Prefecture 7 Fukushima Prefecture 23 Aichi Prefecture 39 Kochi Prefecture 8 Ibaraki Prefecture 24 Mie Prefecture 40 Fukuoka Prefecture 9 Tochigi Prefecture 25 Shiga Prefecture 41 Saga Prefecture 10 Gunma Prefecture 26 Kyoto Prefecture 42 Nagasaki Prefecture 11 Saitama Prefecture 27 Osaka Prefecture 43 Kumamoto Prefecture 12 Chiba Prefecture 28 Hyogo Prefecture 44 Oita Prefecture 13 Tokyo 29 Nara Prefecture 45 Miyazaki Prefecture 14 Kanagawa Prefecture 30 Wakayama Prefecture 46 Kagoshima Prefecture 15 Niigata Prefecture 31 Tottori Prefecture 47 Okinawa Prefecture 16 Toyama Prefecture 32 Shimane Prefecture Local dishes loved by the nation Hokkaido Map No.1 Northern delights Iwate Map No.3 Cool noodles Hokkaido Rice bowl with Tohoku Uni-ikura-don sea urchin and Morioka Reimen Chilled noodles -

Nansei Islands Biological Diversity Evaluation Project Report 1 Chapter 1

Introduction WWF Japan’s involvement with the Nansei Islands can be traced back to a request in 1982 by Prince Phillip, Duke of Edinburgh. The “World Conservation Strategy”, which was drafted at the time through a collaborative effort by the WWF’s network, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), posed the notion that the problems affecting environments were problems that had global implications. Furthermore, the findings presented offered information on precious environments extant throughout the globe and where they were distributed, thereby providing an impetus for people to think about issues relevant to humankind’s harmonious existence with the rest of nature. One of the precious natural environments for Japan given in the “World Conservation Strategy” was the Nansei Islands. The Duke of Edinburgh, who was the President of the WWF at the time (now President Emeritus), naturally sought to promote acts of conservation by those who could see them through most effectively, i.e. pertinent conservation parties in the area, a mandate which naturally fell on the shoulders of WWF Japan with regard to nature conservation activities concerning the Nansei Islands. This marked the beginning of the Nansei Islands initiative of WWF Japan, and ever since, WWF Japan has not only consistently performed globally-relevant environmental studies of particular areas within the Nansei Islands during the 1980’s and 1990’s, but has put pressure on the national and local governments to use the findings of those studies in public policy. Unfortunately, like many other places throughout the world, the deterioration of the natural environments in the Nansei Islands has yet to stop. -

The Chrysomelidae of Japan and the Ryukyu Islands. IV

九州大学学術情報リポジトリ Kyushu University Institutional Repository The Chrysomelidae of Japan and the Ryukyu Islands. IV Kimoto, Shinsaku Hikosan biological laboratory, Department of Agriculture, Kyushu University https://doi.org/10.5109/22722 出版情報:九州大学大学院農学研究院紀要. 13 (2), pp.235-262, 1964-10. 九州大学農学部 バージョン: 権利関係: Journal of the Faculty of Agriculture, Kyushu University, Vol. 13, No. 2 October 30, 1964 The Chrysomelidae of Japan and the Ryukyu Islands. WY”) Shinsaku K IMOTO 3, Subfamily EUMOLPINAE Key to Japanese genera of Ezmzolpinae 1i. Anterior margin of prothoracic episterna convex, more especially near antero- internal angle, the latter generally reflexed ............................................. 2 k-rterior margin of prothoracic episterna straight or concave, antero-internal angle not reflexed ................................................................................. 7 2. Elytra not rugose on each side .................................................................. 3 Elytra more or less transversely rugose on each side behind humeri ......... ........................................................................................................ Abirus 3. Dorsal surface of body glabrous .................................................................. 4 Dorsal surface of body clothed with hairs or scales .................. Acrotlzimhz 1. Intermediate and posterior tibiae not emarginate on outer side near apex ............................................................................................................... 5 Intermediate -

Intertidal Molluscan Fauna in Mageshima Island

INTERTIDAL MOLLUSCAN FAUNA IN MAGESHIMA ISLAND 著者 "YAMAMOTO Tomoko, ISHIDA So" journal or 南太平洋海域調査研究報告=Occasional papers publication title volume 38 page range 93-95 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10232/9808 南太平洋海域調査研究報告 No.38( 2003年2月) OCCASIONALINTERTIDAL PAPERS No. MOLLUSCAN38(February2003) FAUNA IN MAGESHIMA ISLAND 93 INTERTIDAL MOLLUSCAN FAUNA IN MAGESHIMA ISLAND Tomoko YAMAMOTO and So ISHIDA Molluscan fauna of intertidal rocky shores were investigated at Mageshima Island, which is located 12 km west of Tanegashima Island, Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan. Eighty-four species belonging to 31 families were sampled and they included many subtropical species. Some characteristics of this fauna showed that intertidal rocky shores of Mageshima Island were environmentally comparable to cobble shores. Keywords: Fauna, Intertidal, Mollusca Introduction Mageshima Island is located 12 km west of Tanegashima Island and has a 12 km coastline and is 8.5 in surface-area. It is a flat island with a maximum elevation of 71 m. Historically, this island had no residents and was used as a base for fishing or as a farm except from 1951 to 1980, when more than 500 people reclaimed the island and resided to cultivate sugarcane. The coast of the island is known for a good abalone fishery. Therefore, we can expect that this island has a preferable environment for coastal organisms because of very low human impact on intertidal shores and having subtidal shores which can persevere rich abalone resources. There have been some studies dealing with terrestrial flora and fauna of Mageshima Island (SASAKI et al., 1960; NAKAMINE, 1976). One subspecies of sika deer, , was described from this island (KURODA & OKADA, 1950). -

Kenji Suetsugu: New Locality of the Mycoheterotrophic Orchid Gastrodia Fontinalis from Kuroshima Island, Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan

J. Jpn. Bot. 91(6): 358–361 (2016) Kenji SUETSUGU: New Locality of the Mycoheterotrophic Orchid Gastrodia fontinalis from Kuroshima Island, Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan Department of Biology, Graduate School of Science, Kobe University, 1-1, Rokkodai, Nada-ku, Kobe, 657-8501, JAPAN E-mail: [email protected] Summary: I found Gastrodia fontinalis T. P. Lin based on a collection from Mt. Pataoerh in Taipei (Orchidaceae) in bamboo forests on Kuroshima County, Taiwan (Lin 1987). This species was Island, the northernmost island of the Ryukyu previously considered as an endemic Taiwanese Islands in Japan. This habitat represents the species. Recently, Suetsugu et al. (2014) found northernmost locality of the species. the species in a bamboo forest on Takeshima Island in Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan. During The genus Gastrodia (Orchidaceae) is a the recent field survey on Kuroshima Island, I group of mycoheterotrophic orchids distributed found additional populations of G. fontinalis in temperate and tropical areas of Madagascar, in bamboo forests from the Island. This habitat Asia, and Oceania (Chung and Hsu 2006). The represents the northernmost locality of the genus, which contains approximately 80 species, species. Here I report the new locality with a is characterized by a fleshy tuber or coralloid description of the specimens from the Island. underground stem, an absence of leaves, the union of sepals and petals, and two mealy Gastrodia fontinalis T. P. Lin, Native pollinia without caudicles (Chen et al. 2009, Orchids of Taiwan 3: 129 (1987). [Fig. 1] Govaerts et al. 2016). Terrestrial, mycoheterotrophic herb. Root G a s t ro d i a shows extraordinary short, densely branching, mostly extending morphological diversity. -

INDEX of Records of the U. S. Strategic Bombing Survey; Entry 55, Carrier-Based Navy and Marine Corps Aircraft Action Reports, 1944-1945

INDEX of Records of the U. S. Strategic Bombing Survey; Entry 55, Carrier-Based Navy and Marine Corps Aircraft Action Reports, 1944-1945 (1) Task Group 12.4 Action Report of Task Group 12.4 against Wake Island, 13 June 1945 through 20 June 1945 ※Commander Task Group 12.4 (Commander Carrier Division 11). (2) Task Group 38.1 Report of Operations of Task Group 38.1 against the Japanese Empire 1 July 1945 to 15 August 1945 ※Commander Task Group 38.1 (Commander Carrier Division 3 - Rear Admiral T. L. Sprague, USN, USS Bennington, Flagship). (3) Task Group 38.4 Action Report, Commander Task Group 38.4, 2 July to 15 August 1945, Strikes against Japanese Home Islands ※Commander Task Group 38.4 (Commander Carrier Division 6, Rear Admiral A. W. Radford, US Navy, USS Yorktown, Flagship). (4) Task Group 52.1.1 Report of Capture of Okinawa Gunto, Phases I and II, 24 May 1945 to 24 June 1945 ※Commander Task Unit 52.1.1(24 May to 28 May), Commander Task Unit 32.1.1. Action Report, Capture of Okinawa Gunto, Phases 1 and 2 - 21 March 1945 to 24 May 1945 ※Commander Task Unit 52.1.1 (Support Carrier Unit 1) from 9 March 1945 to 10 May 1945 and CTG Task Unit 52.1.1 from 17 May to 24 May 1945 (Commander Carrier Division 26). (5) Task Group 52.1.2 Action Report - Capture of Okinawa Gunto, Phases 1 and 2, 21 March to 29 April 1945 ※Commander Task Unit 52.1.2 (21 March - 29 April, incl) and Commander Task Unit 51.1.2 (21-25 March, inclusive) (Commander Car-rier Division 24). -

Those on the Latter by Katayama (I) and Minamibuchi (I)

GENETIC STRUCTURE OF HUMAN POPULATIONS III. DIFFERENTIATION OF ABO BLOOD GROUP GENE FREQUENCIES IN SMALL AREAS OF JAPAN* MASATOSHI NEI and YOKO IMAIZUMI Division of Genetics, National Institute of Radiological Sciences, Chiba, Japan Receivedii .xii.65 1.INTRODUCTION INa previous paper (Nei and Imaizumi, 1966a) it was shown that the local differentiation of ABO and MitT blood group gene frequencies in Japan has occurred largely by genetic random drift. In that investi- gation the population of Japan was divided into 45 different sub- populations or Prefectures (administrative units of Japan) the sizes of which were mostly one to two millions. However, the size of mating groups of neighbourhoods in Wright's (1946) sense appears to be much smaller than the sub-populations employed in the paper. It is, there- fore, expected that the gene frequencies are locally differentiated even within these sub-populations. We thus examined the degree of differ- entiation of ABO blood group gene frequencies in several small areas of Japan. 2.DIFFERENTIATION WITHIN PREFECTURES Thereare two Prefectures, in which the local variation of ABO blood group gene frequencies can be analysed. One is Kagoshima Prefecture in Kyushu Island and the other Tokushima Prefecture in Shikoku Island (cf fig. i in Nei and Imaizumi, 1966a). The data on the former were collected by Ono and Takagi (1942) and Makisumi (1958), and those on the latter by Katayama (i) and Minamibuchi (i). The areas of Kagoshima and Tokushima Prefectures are 9,104 km2 and 4,143 km2 respectively, both including several neighbouring small islands. The population sizes of these two Prefectures at the time of 1960 census are 1,962,998 and 847,279 respectively. -

6-2-5-④ 6-2-5-③ Kyusyu 6-2-5 (Map 6-2-5) Province: Kumamoto Pref

6-2-5-④ 6-2-5-③ Kyusyu 6-2-5 (Map 6-2-5) Province: Kumamoto Pref. at west, Oita Pref. at northeast, Miyazaki Pref. at southeast, and Kagoshima Pref. at south of Kyushu Location: Kyushu lies at west of Shikoku and southwest of Honshu Air temperature: 17.8˚C (annual average, at Ushibuka City, Kumamoto.) Seawater temperature: 22.9˚C, 22.2 ˚C and 20.9 ˚C (annual average, at east off Aburatsu, southwest off Kushikijima (Is.) and Yatsushiro Sea, respectively) Precipitation: 2,027.9 mm (annual average, Ushibuka City, Kumamoto) Total area of coral communities: 581.8 ha Protected areas: Unzen-Amakusa National Park: at around Amakusa, including 3 Marine Park Zones and 2 Protected Water Surfaces; Nippo Kaigan Quasi-National Park: coastline at south of Oita and north of Miyazaki, including 2 Marine Park Zones; Nichinan Kaigan Quasi-National Park: coastline at south of Miyazaki and east of Kagoshima, including 1 Marine Park Zone; Kirishima-Yaku National Park: a part of coastline in Kagoshima, including 2 Marine Park Zones. 6-2-5-① *“号”on this map means“site”. 6-2-5-⑤ 6-2-5-② *“号”on this map means“site”. 6-2-5-② 6-2-5-① *“号”on this map means“site”. 6-2-5-④ 6-2-5-③ *“号”on this map means“site”. 6-2-5-⑤ 06 Coral Reefs of Japan a. Kumamoto Prefecture (Map 6-2-5-①) Satoshi Nojima 1 Corals and coral reefs Photo. 1. Tabulate Acropora dominant community in Kuwashima 1. Geographical features (Is.), Ushibuka City, Kumamoto Prefecture. On the west of Kyushu in Kumamoto Prefecture lie the Amakusa Islands. -

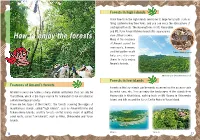

How to Enjoy the Forests Many of the Creatures of Amami Cannot Be Seen Easily, However

Forests in high islands Thick forests in the high islands are home to large fern plants such as flying spider-monkey tree ferns, and you can enjoy the atmosphere of subtropical forests. The observatories on Mt. Yuwandake and Mt. Yui in Amami-Oshima Island offer a panoramic view of their crowns. How to enjoy the forests Many of the creatures of Amami cannot be seen easily, however, certified guides would Tokunoshima spiny rat help you discover them to fully enjoy Amami's forests. Mt.Yuwandake(Amami-Oshima Is.) Forests in low islands Features of Amami’s forests Forests in the low islands can be easily accessed via the access roads Amami's forests are home to many animals and plants that can only be by rental cars, etc. You can enjoy the landscapes of the islands from found there, which is the major reason for nomination to be inscribed as Hyakunodai in Kikai Island, walking trails on Mt. Oyama in Okinoerabu a World Heritage property. Island, and hills around the Yoron Castle Ruins in Yoron Island. There are two types of the forests: the forests covering the ridges of mountainous islands, called “high islands”, such as Amami-Oshima and Tokunoshima Islands; and the forests on flat islands made of uplifted coral reefs, called “low islands”, such as Kikai, Okinoerabu and Yoron Islands. Kikai Is. Yoron Is. 16 17 To protect nature of Amami Areas that require special attention for protection Thanks to the wonderful nature and culture, the Amami Islands were designated as the Amamigunto National Park in 2017. Please respect the following rules in the National Park and en- ■ Kinsakubaru Forest, Amami-Oshima Island joy nature of Amami.