Social Transformations in Contemporary Society 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 2008 Marks the 5Th Anniversary Since the Setting up Of

September 2008 marks the 5th anniversary since the setting up of the Sikh Federation (UK), During this period, we have won the respect of all the major UK political parties as a result of the way we have conducted ourselves and our campaigns. Our strengths and standing in the community is widely recognised by Sikhs, politicians, non- Sikh groups and the media. In this respect the Sikh Federation (U K) as an orqanlsation is % unrivalled in the British Sikh community. Unlike many others the Federation is not prepared to compromise or water down its aims and objectives and for this reason there is a constant pro-Indian Government lobby. The extent to which the UK Government has been prepared to acknowledge working with the Federation therefore remains a challenge. Each year a member of the Shadow Cabinet hasattended the Annual Convention we organise and pledged support for our work and backing for some of our key campaigns. There is however still some way to go for the pledges of support to be turned into concrete action and results. In the near future, we will probably see a change of government. One benefit of this may be delivery on the pledges made. The last two years has also seen the importance of the organisation grow on the international stage. Increasingly Sikhs in mainland Europe and other parts of the world look to the Sikh Federation (UK) to take the lead in political lobbying internationally and guiding them on national campaigns to obtain equal rights for Sikhs. The next few years present a critical period for the organisation to develop and consolidate its position in the UK by working with all the major political parties and continuing to lead major international campaigns, International co-operation with like minded organisations is increasingly resulting in more governments seeing the advantages of having a permanent Sikh voice on the international stage. -

The Sikh Prayer)

Acknowledgements My sincere thanks to: Professor Emeritus Dr. Darshan Singh and Prof Parkash Kaur (Chandigarh), S. Gurvinder Singh Shampura (member S.G.P.C.), Mrs Panninder Kaur Sandhu (nee Pammy Sidhu), Dr Gurnam Singh (p.U. Patiala), S. Bhag Singh Ankhi (Chief Khalsa Diwan, Amritsar), Dr. Gurbachan Singh Bachan, Jathedar Principal Dalbir Singh Sattowal (Ghuman), S. Dilbir Singh and S. Awtar Singh (Sikh Forum, Kolkata), S. Ravinder Singh Khalsa Mohali, Jathedar Jasbinder Singh Dubai (Bhai Lalo Foundation), S. Hardarshan Singh Mejie (H.S.Mejie), S. Jaswant Singh Mann (Former President AISSF), S. Gurinderpal Singh Dhanaula (Miri-Piri Da! & Amritsar Akali Dal), S. Satnam Singh Paonta Sahib and Sarbjit Singh Ghuman (Dal Khalsa), S. Amllljit Singh Dhawan, Dr Kulwinder Singh Bajwa (p.U. Patiala), Khoji Kafir (Canada), Jathedar Amllljit Singh Chandi (Uttrancbal), Jathedar Kamaljit Singh Kundal (Sikh missionary), Jathedar Pritam Singh Matwani (Sikh missionary), Dr Amllljit Kaur Ibben Kalan, Ms Jagmohan Kaur Bassi Pathanan, Ms Gurdeep Kaur Deepi, Ms. Sarbjit Kaur. S. Surjeet Singh Chhadauri (Belgium), S Kulwinder Singh (Spain), S, Nachhatar Singh Bains (Norway), S Bhupinder Singh (Holland), S. Jageer Singh Hamdard (Birmingham), Mrs Balwinder Kaur Chahal (Sourball), S. Gurinder Singh Sacha, S.Arvinder Singh Khalsa and S. Inder Singh Jammu Mayor (ali from south-east London), S.Tejinder Singh Hounslow, S Ravinder Singh Kundra (BBC), S Jameet Singh, S Jawinder Singh, Satchit Singh, Jasbir Singh Ikkolaha and Mohinder Singh (all from Bristol), Pritam Singh 'Lala' Hounslow (all from England). Dr Awatar Singh Sekhon, S. Joginder Singh (Winnipeg, Canada), S. Balkaran Singh, S. Raghbir Singh Samagh, S. Manjit Singh Mangat, S. -

Indian Archaeology 1994-95 a Review

INDIAN ARCHAEOLOGY 1994-95 — A REVIEW EDITED BY HARI MANJHI C. DORJE ARUNDHATI BANERJI PUBLISHED BY THE DIRECTOR GENERAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA GOVERNMENT OF INDIA JANPATH, NEW DELHI 2000 front cover : Gudnapura, general view of remains of a brick temple-complex back cover : Kanaganahalli, drum-slab depicting empty throne and Buddhdpada flanked by chanri bearers and devotees © 2000 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA GOVERNMENT OF INDIA Price : Rs. 330.00 PRINTED AT M/S BENGAL OFFSET WORKS, 335, KHAJOOR ROAD, NEW DELHI - 110005 PREFACE In bringing out this annual Review after a brief gap of one month, I warmly acknowledge the contributions of all my colleagues in the Survey as also those in the State Departments, Universities and various other Institutions engaged in archaeological researches for supplying material with illustrations for inclusion in this issue. I am sure, that, with the co-operation of all the heads of respective departments, we will soon be able to further reduce the gap in the printing of the Review. If contributions are received in time in the required format and style, our task of expediting its publication will be much easier. The material incorporated herein covers a wide range of subjects comprising exploration and excavation, epigraphical discoveries, development of museums, radio-carbon dates, architectural survey of secular and religious buildings, structural/chemical conservation etc. During the period under review many new discoveries have been reported throughout the country. Among these the survey of buildings in and around Vrindavan associated with mythological tradition is particularly interesting. I would like to place on record my sincere thanks to my colleagues Shri Hari Manjhi, Shri C. -

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Educational Research

Volume 9, Issue 8(4), August 2020 International Journal of Multidisciplinary Educational Research Published by Sucharitha Publications Visakhapatnam Andhra Pradesh – India Email: [email protected] Website: www.ijmer.in Editorial Board Editor-in-Chief Dr.K. Victor Babu Associate Professor, Institute of Education Mettu University, Metu, Ethiopia EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS Prof. S. Mahendra Dev Prof. Igor Kondrashin Vice Chancellor The Member of The Russian Philosophical Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Society Research, Mumbai The Russian Humanist Society and Expert of The UNESCO, Moscow, Russia Prof.Y.C. Simhadri Vice Chancellor, Patna University Dr. Zoran Vujisiæ Former Director Rector Institute of Constitutional and Parliamentary St. Gregory Nazianzen Orthodox Institute Studies, New Delhi & Universidad Rural de Guatemala, GT, U.S.A Formerly Vice Chancellor of Benaras Hindu University, Andhra University Nagarjuna University, Patna University Prof.U.Shameem Department of Zoology Prof. (Dr.) Sohan Raj Tater Andhra University Visakhapatnam Former Vice Chancellor Singhania University, Rajasthan Dr. N.V.S.Suryanarayana Dept. of Education, A.U. Campus Prof.R.Siva Prasadh Vizianagaram IASE Andhra University - Visakhapatnam Dr. Kameswara Sharma YVR Asst. Professor Dr.V.Venkateswarlu Dept. of Zoology Assistant Professor Sri.Venkateswara College, Delhi University, Dept. of Sociology & Social Work Delhi Acharya Nagarjuna University, Guntur I Ketut Donder Prof. P.D.Satya Paul Depasar State Institute of Hindu Dharma Department of Anthropology Indonesia Andhra University – Visakhapatnam Prof. Roger Wiemers Prof. Josef HÖCHTL Professor of Education Department of Political Economy Lipscomb University, Nashville, USA University of Vienna, Vienna & Ex. Member of the Austrian Parliament Dr.Kattagani Ravinder Austria Lecturer in Political Science Govt. Degree College Prof. -

Sikhism-A Very Short Introduction

Sikhism: A Very Short Introduction Very Short Introductions are for anyone wanting a stimulating and accessible way in to a new subject. They are written by experts, and have been published in more than 25 languages worldwide. The series began in 1995, and now represents a wide variety of topics in history, philosophy, religion, science, and the humanities. Over the next few years it will grow to a library of around 200 volumes – a Very Short Introduction to everything from ancient Egypt and Indian philosophy to conceptual art and cosmology. Very Short Introductions available now: ANARCHISM Colin Ward CHRISTIANITY Linda Woodhead ANCIENT EGYPT Ian Shaw CLASSICS Mary Beard and ANCIENT PHILOSOPHY John Henderson Julia Annas CLAUSEWITZ Michael Howard ANCIENT WARFARE THE COLD WAR Robert McMahon Harry Sidebottom CONSCIOUSNESS Susan Blackmore THE ANGLO-SAXON AGE Continental Philosophy John Blair Simon Critchley ANIMAL RIGHTS David DeGrazia COSMOLOGY Peter Coles ARCHAEOLOGY Paul Bahn CRYPTOGRAPHY ARCHITECTURE Fred Piper and Sean Murphy Andrew Ballantyne DADA AND SURREALISM ARISTOTLE Jonathan Barnes David Hopkins ART HISTORY Dana Arnold Darwin Jonathan Howard ART THEORY Cynthia Freeland Democracy Bernard Crick THE HISTORY OF DESCARTES Tom Sorell ASTRONOMY Michael Hoskin DINOSAURS David Norman Atheism Julian Baggini DREAMING J. Allan Hobson Augustine Henry Chadwick DRUGS Leslie Iversen BARTHES Jonathan Culler THE EARTH Martin Redfern THE BIBLE John Riches EGYPTIAN MYTH BRITISH POLITICS Geraldine Pinch Anthony Wright EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY Buddha Michael Carrithers BRITAIN Paul Langford BUDDHISM Damien Keown THE ELEMENTS Philip Ball BUDDHIST ETHICS Damien Keown EMOTION Dylan Evans CAPITALISM James Fulcher EMPIRE Stephen Howe THE CELTS Barry Cunliffe ENGELS Terrell Carver CHOICE THEORY Ethics Simon Blackburn Michael Allingham The European Union CHRISTIAN ART Beth Williamson John Pinder EVOLUTION MATHEMATICS Timothy Gowers Brian and Deborah Charlesworth MEDICAL ETHICS Tony Hope FASCISM Kevin Passmore MEDIEVAL BRITAIN FOUCAULT Gary Gutting John Gillingham and Ralph A. -

The Sikhs of the Punjab Revised Edition

The Sikhs of the Punjab Revised Edition In a revised edition of his original book, J. S. Grewal brings the history of the Sikhs, from its beginnings in the time of Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, right up to the present day. Against the background of the history of the Punjab, the volume surveys the changing pattern of human settlements in the region until the fifteenth century and the emergence of the Punjabi language as the basis of regional articulation. Subsequent chapters explore the life and beliefs of Guru Nanak, the development of his ideas by his successors and the growth of his following. The book offers a comprehensive statement on one of the largest and most important communities in India today j. s. GREWAL is Director of the Institute of Punjab Studies in Chandigarh. He has written extensively on India, the Punjab, and the Sikhs. His books on Sikh history include Guru Nanak in History (1969), Sikh Ideology, Polity and Social Order (1996), Historical Perspectives on Sikh Identity (1997) and Contesting Interpretations of the Sikh Tradition (1998). Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008 Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008 THE NEW CAMBRIDGE HISTORY OF INDIA General editor GORDONJOHNSON President of Wolfson College, and Director, Centre of South Asian Studies, University of Cambridge Associate editors C. A. BAYLY Vere Harmsworth Professor of Imperial and Naval History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow of St Catharine's College J F. RICHARDS Professor of History, Duke University Although the original Cambridge History of India, published between 1922 and 1937, did much to formulate a chronology for Indian history and describe the administrative structures of government in India, it has inevitably been overtaken by the mass of new research published over the past fifty years. -

Transnational Learning Practices of Young British Sikhs

This is a repository copy of Global Sikh-ers: Transnational Learning Practices of Young British Sikhs. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/118665/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Singh, J (2012) Global Sikh-ers: Transnational Learning Practices of Young British Sikhs. In: Jacobsen, KA and Myrvold, K, (eds.) Sikhs Across Borders: Transnational Practices of European Sikhs. Sociology of Religion . Bloomsbury , London , pp. 167-192. ISBN 9781441113870 © 2012. This is an Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Bloomsbury Academic in Sikhs Across Borders: Transnational Practices of European Sikhs on 11 Aug 2012, available online: https://www.bloomsbury.com/9781441113870 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 Chapter 9 Global Sikh-ers: Transnational Learning Practices of Young British Sikhs Jasjit Singh My clearest memory of learning about Sikhism as a young Sikh growing up in Bradford in the 1970s is not from attending the gurdwara, or being formally taught about Sikhism in a classroom, but from reading comic books depicting the lives of the Sikh gurus. -

Whoswho 2018.Pdf

Hindi version of the Publication is also available सत㔯मेव ज㔯ते PARLIAMENT OF INDIA RAJYA SABHA WHO’S WHO 2018 (Corrected upto November 2018) सं द, र ी㔯 स ाज㔯 त सभ ार ा भ P A A H R B LI A AM S EN JYA T OF INDIA, RA RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI © RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT, NEW DELHI http://parliamentofindia.nic.in http://rajyasabha.nic.in E-mail: [email protected] EDITORIAL TEAM Shri D. S. Prasanna Kumar Director Smt. Vandana Singh Additional Director Smt. Asha Singh Joint Director Shri Md. Salim Ali Assistant Research Officer Shri Mohammad Saleem Assistant Research Officer PUBLISHED BY THE SECRETARY-GENERAL, RAJYA SABHA AND PRINTED BY DRV GrafIx Print, 41, Shikshak BHAwAN, INSTITUTIonal AREA, D-BLoCK JANAKPURI, NEw DELHI-110058 PREFACE TO THE THIRTY-FOURTH EDITION Rajya Sabha Secretariat has the pleasure of publishing the updated thirty- fourth edition of ‘Rajya Sabha who’s who’. Subsequent to the retirement of Members and biennial elections and bye- elections held in 2017 and 2018, information regarding bio-data of Members have been updated. The bio-data of the Members have been prepared on the basis of information received from them and edited to keep them within three pages as per the direction of the Hon’ble Chairman, Rajya Sabha, which was published in Bulletin Part-II dated May 28, 2009. The complete bio-data of all the Members are also available on the Internet at http://parliamentofindia.nic.in and http://rajyasabha.nic.in. NEW DELHI; DESH DEEPAK VERMA, December, 2018 Secretary-General, Rajya Sabha CONTENTS PAGES 1. -

Simranjit Khalsa

ABSTRACT Practicing Minority Religion: Interrogating the Role of Race, National Belonging, and Gender Among Sikhs in the US and England by Simranjit Khalsa Defying the expectations of scholarship predicting that religion will continue to decline, religion remains an influential force that shapes the lives of everyday people. Religious beliefs and communities provide people with cultural tools to understand the world around them, shape their views and beliefs about other aspects of the social world, and provide community members access to resources. We have little understanding, however, of how status as a religious minority shapes the lives of practitioners and their interactions with people outside of their faith tradition. I turn my attention to this subject by asking how having a minority religious identity is linked to race, national belonging, and constructions of gender. I examine these questions through the Sikh case in the US and England. Sikhs are a religious minority in every nation in which they are present, making them an excellent case to examine these questions. Further, in the US and England they are a particularly visible and distinctive religious minority, and both countries have distinct state relationships to religion, distinct relationships to India, and shared but unique experiences with radical terrorism claiming affiliation with Islam. I draw on 11 months of participant observation with two communities in two national contexts, analyzing data from 79 qualitative interviews to better understand the experience of practicing a minority religion. I find that boundary work is central to the experience of practicing Sikhism for my respondents, shaping their religious practice, the way they go about their lives, and their interactions with non- Sikhs. -

Download Entire Journal Volume [PDF]

JOURNAL OF PUNJAB STUDIES Editors Indu Banga Panjab University, Chandigarh, INDIA Mark Juergensmeyer University of California, Santa Barbara, USA Gurinder Singh Mann University of California, Santa Barbara, USA Ian Talbot Southampton University, UK Shinder Singh Thandi Coventry University, UK Book Review Editor Eleanor Nesbitt University of Warwick, UK Ami P. Shah University of California, Santa Barbara, USA Editorial Advisors Ishtiaq Ahmed Stockholm University, SWEDEN Tony Ballantyne University of Otago, NEW ZEALAND Parminder Bhachu Clark University, USA Harvinder Singh Bhatti Punjabi University, Patiala, INDIA Anna B. Bigelow North Carolina State University, USA Richard M. Eaton University of Arizona, Tucson, USA Ainslie T. Embree Columbia University, USA Louis E. Fenech University of Northern Iowa, USA Rahuldeep Singh Gill California Lutheran University, Thousand Oaks, USA Sucha Singh Gill Punjabi University, Patiala, INDIA Tejwant Singh Gill Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar, INDIA David Gilmartin North Carolina State University, USA William J. Glover University of Michigan, USA J.S. Grewal Institute of Punjab Studies, Chandigarh, INDIA John S. Hawley Barnard College, Columbia University, USA Gurpreet Singh Lehal Punjabi University, Patiala, INDIA Iftikhar Malik Bath Spa University, UK Scott Marcus University of California, Santa Barbara, USA Daniel M. Michon Claremont McKenna College, CA, USA Farina Mir University of Michigan, USA Anne Murphy University of British Columbia, CANADA Kristina Myrvold Lund University, SWEDEN Rana Nayar -

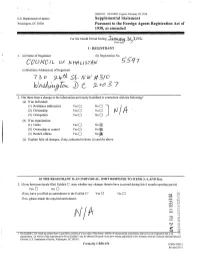

Council of Ichfluzrm B'547 (C) Business Address(Es) of Registrant 7 3 0 %^Tk Si, A/ U/ #3/O

OMB NO. 1124-0002; Expires February 28, 2014 U.S. Department of Justice Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended r For Six Month Period Ending JfyrwHAiy|_3_j b\yJl0)'X ' (Insert date/ I - REGISTRANT 1. (a) Name of Registrant (b) Registration No. Council of icHfluzrM b'547 (c) Business Address(es) of Registrant 7 3 0 %^tk Si, A/ U/ #3/O 2. Has there been a change in the information previously furnished in connection with the following? (a) If an individual: (1) Residence address(es) YesD NoD (2) Citizenship YesD NoD rJlA (3) Occupation YesD NoD J (b) If an organization: (1) Name YesQ No a (2) Ownership or control YesD Nop, (3) Branch offices YesD No a (c) Explain fully all changes, if any, indicated in Items (a) and (b) above. IF THE REGISTRANT IS AN INDIVIDUAL, OMIT RESPONSE TO ITEMS 3, 4, AND 5(a). 3. If you have previously filed Exhibit C1, state whether any changes therein have occurred during this 6 month reporting period. Yes D No n Ifyes, have you filed an amendment to the Exhibit C? Yes __ No • rsj If no, please attach the required amendment. |ss3 m m C3 /v CO 15 TO r\> o 1 The Exhibit C, for which no printed form is provided, consists of a true copy ofthe charter, articles ot incorporation, association, and by laws of a registrant that is an JTS organization. (A waiver ofthe requirement to file an Exhibit C may be obtained for good cause upon written application to the Assistant Attorney General, National Security Division, U.S. -

09 LIBRARY RARE BOOK COLLECTION DETAILS S.No Acc No Title Author Publisher Year 1 5680 Examples in Applied Lamb C.B L

THIAGARAJAR COLLEGE, MADURAI – 09 LIBRARY RARE BOOK COLLECTION DETAILS S.No Acc_No Title Author Publisher Year 1 5680 Examples In Applied Lamb C.B L. Reeve &Co 1872 Electricity 2 4253 Carlyle Nichol (John) Macmillan&Co 1880 3 6276 Siva Raththiri Puranam Nellai Naathar Scottin Yandira Saalai 1881 4 2974 Polland W.R.Marfill T.Fisher Unwin London 1885 5 2881 Aunt Sarah Of The War Burns And Oales Ltd Burns And Oales Ltd 1888 London London 6 2934 Greifenstein F.Marion Crawford T.Nelson And Sons Ltd 1889 London 7 2935 Whittier ( The Cameo Poet ) Whittier Whittier 1889 8 2931 Marzios Crucifix F.Marion Crawford Macmillan And Co 1891 London 9 1277 Mr Wee L.G.Miln Canell And Co Ltd 1893 London 10 2906 The Berothed And The Sir Walter Scott The Gresham Publishing 1893 Highland Window And Co London 11 6612 Thiruvalluvar Samanar Ennum Thillai Naatha Naavalar Ganesa Achagam 1894 Kollai Maruppu 12 1279 Versons Aunt Sara Jeannette Duccan Chatts Windhs 1894 13 2994 Prime Henry The Navigetor C.Raymond Beasley G.P.Putnans And Sons 1895 London 14 1103 Sandy Married Dordthen Couyers Methueu And Company 1895 Ltd 15 1109 Liver Of Great Composers Vol Beethovan Of The Penguin Book Series 1895 I Romanties 16 2920 The Riddle Of The Sands Erskine Childers T.Nelson And Sons Ltd 1895 London 17 3329 Philip Augustins W.H Hutton Macmillan& Co Ltd, 1896 London 18 2316 Flame Of Geierstein Or The Scott (Walter) The Gresham Publishing 1896 Maiden Of The Must And Co London 19 6253 Kumana Sariththiram Kandasamykh Arunagiri Mudaliar 1897 Moolamum Arumparavurai Kaviraayar M.Ra Vum 20 26517 Nao Industrial State Galbraith (John Penguin Books 1897 Kenneth) 21 1057 The Works Of Osean Wilde O.Wilde Collins London 1898 (1850-1900 ) 22 1061 Stories From Dante E.H.B.Wither K.T.L.