AAAA EUROPEAN ROOTS WINKELRIED Anner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Das Alte Sempacherlied B

The Ancient Song of Sempach Of bold forefathers in days of old Let their heroic feats be told Of the lance striking home and the clash of swords dire, Of battle dust and the vapor of blood on fire! Our sacred song we dedicate to Winkelried; He is our hero. For us he did bleed. “Look after my wife and child so dear, To you I entrust them without fear!” Calling out to his men before the foe, Strong Struthan grabbed the long spear and forced it low, Burying it in his powerful chest was his decree, To die with God in his heart for the right to be free. And over the body blessed His heroic comrades swiftly pressed On home terrain Swiss swords like lightning fell The murderous horde to quell; And freedom’s victory all hail In all ages hence from mountain to dale. The German lyrics of “The Ancient Song of Sempach” and the following excerpt have been translated by Norman Barry from: Dr. Hans Rudolf Fuhrer’s excellent article “Arnold Winkelried – der Held von Sempach 1386” in PALLASCH, Zeitschrift für Miltärgeschichte [= The Magazine for Military History, published in Salzburg, Austria] (Organ der Österreichischen Gesellschaft für Mlitärgeschichte), No. 23, Autumn 2006, p. 71. Was there an historic Arnold von Winkelried? One year later Peter F. Kopp noted that The ground-breaking dissertation by Beat today’s critically-minded historians are Suter entitled “Arnold von Winkelried, the Hero unanimously of the opinion that neither the of Sempach,” completed in 1977, explicitly heroic feat nor a Winkelried can be ascribed to brackets this question out. -

NATIONAL IDENTITY in SCOTTISH and SWISS CHILDRENIS and YDUNG Pedplets BODKS: a CDMPARATIVE STUDY

NATIONAL IDENTITY IN SCOTTISH AND SWISS CHILDRENIS AND YDUNG PEDPLEtS BODKS: A CDMPARATIVE STUDY by Christine Soldan Raid Submitted for the degree of Ph. D* University of Edinburgh July 1985 CP FOR OeOeRo i. TABLE OF CONTENTS PART0N[ paos Preface iv Declaration vi Abstract vii 1, Introduction 1 2, The Overall View 31 3, The Oral Heritage 61 4* The Literary Tradition 90 PARTTW0 S. Comparison of selected pairs of books from as near 1870 and 1970 as proved possible 120 A* Everyday Life S*R, Crock ttp Clan Kellyp Smithp Elder & Cc, (London, 1: 96), 442 pages Oohanna Spyrip Heidi (Gothat 1881 & 1883)9 edition usadq Haidis Lehr- und Wanderjahre and Heidi kann brauchan, was as gelernt hatq ill, Tomi. Ungerar# , Buchklubg Ex Libris (ZOrichp 1980)9 255 and 185 pages Mollie Hunterv A Sound of Chariatst Hamish Hamilton (Londong 197ý), 242 pages Fritz Brunner, Feliy, ill, Klaus Brunnerv Grall Fi7soli (ZGricýt=970). 175 pages Back Summaries 174 Translations into English of passages quoted 182 Notes for SA 189 B. Fantasy 192 George MacDonaldgat týe Back of the North Wind (Londant 1871)t ill* Arthur Hughesp Octopus Books Ltd. (Londong 1979)t 292 pages Onkel Augusta Geschichtenbuch. chosen and adited by Otto von Grayerzf with six pictures by the authorg Verlag von A. Vogel (Winterthurt 1922)p 371 pages ii* page Alison Fel 1# The Grey Dancer, Collins (Londong 1981)q 89 pages Franz Hohlerg Tschipog ill* by Arthur Loosli (Darmstadt und Neuwaid, 1978)9 edition used Fischer Taschenbuchverlagg (Frankfurt a M99 1981)p 142 pages Book Summaries 247 Translations into English of passages quoted 255 Notes for 58 266 " Historical Fiction 271 RA. -

Download.Php?Id=422 E136d4ac (PDF-Dokument)

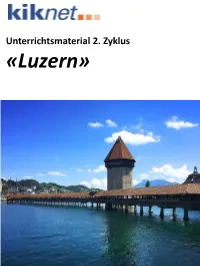

Unterrichtsmaterial 2. Zyklus «Luzern» Luzern 2. Zyklus Lektionsplan Nr. Thema Worum geht es?/Ziele Inhalt und Action Sozialform Material Zeit AB «Die Form des Kreativität fördern anhand mitgebrachter Zeitungen/Zeitschriften Vierwaldstättersees» Gedächtnis anregen, eigene Lernwege zur 1 Icebreaker die Umrisse des Vierwaldstättersees in einer EA/GA Zeitungen/Zeitschriften 20` Erinnerung an die Form des Reisscollage darstellen Leimstifte Vierwaldstättersees zulassen A3-Papier wichtige Kennzahlen und Fakten zum Kanton SuS suchen die verlangten Informationen rund AB «Facts and Figures» und der Stadt finden und kennen um Luzern aus dem Internet zusammen. Lösungen «Facts and Figures» 2 Facts and Figures EA 30` evtl. Vergleich mit dem Selbstständige Korrektur anhand eines PC oder Tablet mit Heimatkanton/Heimatort Lösungsblattes. Internetzugang Erarbeiten und Vertiefen des Wissens über den Tourismus in Luzern und in der Schweiz AB «Gäste aus der Ferne» SuS stellen Mutmassungen über den Tourismus allgemein AB «Deutsch für Luzern-Touristen» Gäste aus der in Luzern an und bringen ihr Vorwissen ein. 3 Fremdsprachenkenntnisse erweitern und GA/Plenum Wörterbücher 45` Ferne SuS erstellen ein eigenes Wörterbuch mit den vertiefen evtl. Zugang zu Online- wichtigsten Begriffen für Touristen in Luzern. Vorwissen in verschiedenen Sprachen Wörterbüchern einbringen AB «Geschichte des Kantons SuS recherchieren selbstständig zu Geschichte des einen Überblick über unterschiedliche -

Grafische Sammlung Historischer Verein Nidwalden Inventar Der Grafischen Sammlung Des Historischen Vereins Nidwalden in Der Kantonsbibliothek

AMT FÜR KULTUR KANTONSBIBLIOTHEK Engelbergstrasse 34, 6371 Stans, Tel 041 618 73 00, www.kantonsbibliothek.nw.ch Grafische Sammlung Historischer Verein Nidwalden Inventar der Grafischen Sammlung des Historischen Vereins Nidwalden in der Kantonsbibliothek Erstellt von Adrian Felber, Heinz Nauer im Sommer / Herbst 2014 Signatur: HGRA Umfang: 638 Grafiken Provenienz: Die Grafische Sammlung ist Teil des Depotbestandes des Historischen Vereins in der Kantonsbibliothek Nidwalden; die allermeisten Grafiken stammen aus dem 18. / 19. Jhd. und wurden vom Historischen Verein zwischen 1864 (Gründungsjahr) und ca. 1910 gesammelt Bemerkungen zum Inventar: Das vorliegende Inventar folgt in seinem Aufbau einem älteren Inventar, welches zwischen 2000 und 2006 von Sibylle von Matt im Rahmen einer umfassenden Restaurierung der Sammlung erstellt wurde. Die Sammlung ist in sechs Formatgruppen („Mini“, „Klein“, „Mittel“, „Normal“, „Gross“, „Überformat“) aufgeteilt. Innerhalb der einzelnen Formatgruppen sind die Grafiken thematisch geordnet. Eine quantitative Übersicht über Formatgruppen und inhaltliche Ordnung findet sich unten. Die Angaben im Inventar zur Herstellungstechnik folgen den handschriftlichen Angaben im Restaurierungsprotokoll von Sibylle von Matt. Im Feld „Bemerkungen“ sind in erster Linie handschriftliche Vermerke auf den einzelnen Grafiken aufgeführt (häufig Datierungen). AMT FÜR KULTUR KANTONSBIBLIOTHEK Engelbergstrasse 34, 6371 Stans, Tel 041 618 73 00, www.kantonsbibliothek.nw.ch QUANTITATIVE ZUSAMMENFASSSUNG MINIFORMAT Schachtel Nr. 1: "Stans" 40 Schachtel Nr. 2: "Kehrsiten, Rotzberg, Stansstad" 26 Schachtel Nr. 3: "Buochs, Beckenried, Niederrickenbach Hergiswil, Pilatus, Engelberg" 31 Schachtel Nr. 4: "Unterwalden, Vierwaldstädtersee" 24. Schachtel Nr. 5: "Trachten" 19 Schachtel Nr. 6: "Gruppen- und Heiligenbilder, Altarbilder" 27 Schachtel Nr. 7: "Winkelried, Scheuber, Pestalozzi und weitere Portraits 32 Schachtel Nr. 8: "Portraits gleicher Serie" 38 Schachtel Nr. -

Schwyzerdütsch Swiss Anti-Prohibition Propaganda Poster by Gantner Printed by Louis Bron, Geneva 1908

Schwyzerdütsch Swiss Anti-Prohibition Propaganda Poster by Gantner Printed by Louis Bron, Geneva 1908 This translation copyright 2005 © Oxygenee.com 1 Electronic reproduction without permission strictly prohibited. Schwyzerdütsch Swiss Anti-Prohibition Propaganda Poster by Gantner Printed by Louis Bron, Geneva 1908 Federal Vote 5 July, 19081 Honored Confederates! Honored Fellow Citizens from every Canton, of every walk of life! Due to a handful of zealots, a law2 was passed last year in Geneva against absinthe. A law about which every true, free Swiss citizen should be ashamed. Now these damn bible-thumpers believe that they can force through a similar law in the whole of Switzerland. What would our old freedom fighters like Tell3 and Winkelried4, like the heroes of Morgarten5, Sempach6, Laupen7, Murten8 and so forth, actually have said if someone had told them they could only drink milk and herbal tea? And it will come to that dear people if you let yourselves be shackled, and let them ban Absinthe in our beloved old Switzerland. Not only do they want to deny you your schnapps, but with time your wine and your beer as well. They – these hypocrites – say this isn’t true, but we found it printed in black and white, in a report from an old Guttempler9, page 28. There, Dr Herco10 from Lausanne states unambiguously: The ban on Absinthe will only have a mild effect on alcoholism in general. What we are striving for in the distant future is to abolish all alcoholic drinks, wine and beer included. It is but a beginning… Yes, yes, you sneaks, you won’t achieve your goal so quickly: we want to bar you from achieving it from the beginning. -

The Writings of James Fenimore Cooper •Fl an Essay Review

Studies in English, New Series Volume 5 Special American Literature Issue, 1984-1987 Article 15 1984 The Writings of James Fenimore Cooper — An Essay Review Hershel Parker The University of Delaware Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/studies_eng_new Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Parker, Hershel (1984) "The Writings of James Fenimore Cooper — An Essay Review," Studies in English, New Series: Vol. 5 , Article 15. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/studies_eng_new/vol5/iss1/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Studies in English at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in English, New Series by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Parker: The Writings of James Fenimore Cooper — An Essay Review THE WRITINGS OF JAMES FENIMORE COOPER - AN ESSAY REVIEW HERSHEL PARKER THE UNIVERSITY OF DELAWARE Of the nine volumes under review I have already reviewed two, The Pioneers and The Pathfinder, in the September 1981 Nineteenth- Century Fiction. I will not repeat myself much. Working from the outside in, I praise first the dust jackets. The cover illustrations are striking, even gorgeous reproductions of early illustrations of scenes from Cooper’s novels and of scenes he describes in his travel books: for The Pioneers, “Turkey Shoot” by Tompkins H. Matteson; for The Pathfinder, a depiction by F. O. C. Darley of Natty Bumppo and his friends hiding, in Natty’s case not very furtively, from the “accursed Mingos”; for Wyandotte, a depiction by Darley of Nick escorting Major Willoughby and Maud to the Hut; for The Last of the Mohicans a sumptuous reproduction of Thomas Cole’s “Cora Kneeling at the Feet of Tamenund”; for Lionel Lincoln an engraving by John Lodge of a drawing by Miller called “View of the Attack on Bunker’s Hill, with the Burning of Charles Town, June 17, 1775”; for Switzerland the Castle of Spietz, Lake of Thun, by W. -

Karl Heinrich Ulrichs

Hubert Kennedy Karl Heinrich Ulrichs Pioneer of the Modern Gay Movement Peremptory Publications San Francisco 2002 © 2002 by Hubert Kennedy Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, Pioneer of the Modern Gay Movement is a Peremtory Publica- tions eBook. It may be freely distributed, but no changes may be made in it. An eBook may be cited the same as a printed book. Comments and suggestions are welcome. Please write to [email protected]. 2 3 When posterity will one day have included the persecution of Urnings in that sad chapter of other persecutions for religious belief and race—and that this day will come is beyond all doubt—then will the name of Karl Heinrich Ulrichs be constantly remembered as one of the first and noblest of those who have striven with courage and strength in this field to help truth and charity gain their rightful place. Magnus Hirschfeld, Foreword to Forschungen über das Rätsel der mannmännlichen Liebe (1898) Magnus Hirschfeld 4 Contents Preface 6 1. Childhood: 1825–1844 12 2. Student and Jurist: 1844–1854 18 3. Literary and Political Interests: 1855–1862 37 4. Origins of the “Third Sex” Theory: 1862 59 5. Researches on the Riddle of “Man-Manly” Love: 1863–1865 67 6. Political Activity and Prison: 1866–1867 105 7. The Sixth Congress of German Jurists, More “Researches”: 1867–1868 128 8. Public Reaction, The Zastrow Case: 1868–1869 157 9. Efforts for Legal Reform: 1869 177 10. The First Homosexual Magazine: 1870 206 11. Final Efforts for the Urning Cause: 1871–1879 217 12. Last Years in Italy: 1880–1895 249 13. -

An Exploration of Environmental Issues Anjali

P: ISSN No. 0976-8602 RNI No. UPENG/2012/42622 VOL.-III, ISSUE-III, JULY-2014 E: ISSN No. 2349-9443 Asian Resonance Arcadian Wilderness in James Fenimore Cooper - An Exploration of Environmental Issues Abstract The paper examines the idea of Arcadian wilderness in the Leather stocking tales of James Fenimore Cooper in the light of eco- criticism. What exactly is eco-criticism? How can we define it? Eco- criticism is a study of literature that focuses on the relationship between humans and their natural world. It believes that humanity‘s disconnection from the natural world is the reason for the environmental crisis today. Eco-criticism believes that nature, non-human beings have been side- lined because of our anthropocentric biases, which tends to exploit the non-human as a resource for our personal gains and comforts. Eco- criticism also values bio-ethics above cultural ethics. It values tribal, aboriginal values as these people lived close to the soil. The American Indian despite all his violence was steeped in his environment in a way modern man never can be. As Cheryll Glotfelty has said in1994 that eco- criticism has one foot in literature and one in land (Glotfelty).Therefore, th Cooper, this 19 century novelist, said to be the father of American fiction, will be evaluated in the context of the current day environmental concerns. Keywords: Eco-criticism, Environment, Nature, non-human, animals, red Indians, wilderness Anjali Raman Introduction Assistant Professor Eco-criticism primarily examines the nature of our interaction with our Shivaji College, environment and its non-human inhabitants. -

Die Sempacher Literatur Von 1779-1935 Mit Besonderer Berücksichtigung Der Schlacht

Die Sempacher Literatur von 1779-1935 mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Schlacht Autor(en): Weber, Peter Xaver Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Der Geschichtsfreund : Mitteilungen des Historischen Vereins Zentralschweiz Band (Jahr): 90 (1935) PDF erstellt am: 06.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-118077 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch Die Sempacher Literatur von 1779-1935 mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Schlacht. Von P. X. Weber. Allgemeine Bemerkung: Der Name Sempach wird zuweilen mit S abgekürzt. Zusammenstellungen über Quellen und Literatur; Haller Gottlieb Emmanuel von, Bibliothek der Schweizer Geschichte, 1788. Hauptregister. Brandstetter, Dr. Jos. Leopold, Literaturübersicht der V Orte, im Geschichtsfreund. -

Denkmal Für Unsern Vaterländischen Helden Arnold Von Winkelried an Seiner Wohnstätte Bei Stans in Unterwalden

Denkmal für unsern vaterländischen Helden Arnold von Winkelried an seiner Wohnstätte bei Stans in Unterwalden Autor(en): Odermatt, F. / Ziegler, Ed. Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Berner Schulfreund Band (Jahr): 2 (1862) Heft 4 PDF erstellt am: 09.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-675434 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch 63 Denkmal für unsern vaterländischen Helden Arnold von Winkelricd an seiner Wohnstätte bei Stans in Unterwalden. Aufruf. 1. Januar 1860. Im Jahr 1861 erließ der schweizerische Kunstverein eine Einla- dung zu Beiträgen für Erstellung eines Winkelried-Denkmals. Der Gedanke zu einem solchen trat schon 1857 beim eidgenössischen Schützen- seste in Luzern zu Tage, und wurde die Sache vom Gemeinderathe von Stans sofort mit Freudigkeit ergrissen. -

American Culture of Servitude: the Problem of Domestic Service in Antebellum Literature and Culture

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--English English 2017 AMERICAN CULTURE OF SERVITUDE: THE PROBLEM OF DOMESTIC SERVICE IN ANTEBELLUM LITERATURE AND CULTURE Andrea Holliger University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.391 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Holliger, Andrea, "AMERICAN CULTURE OF SERVITUDE: THE PROBLEM OF DOMESTIC SERVICE IN ANTEBELLUM LITERATURE AND CULTURE" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--English. 61. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/english_etds/61 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the English at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--English by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

"Indian" Novels of Jose De Alencar

7 Nationality and the "Indian" Novels of Jose de Alencar Cooper's Leather-stocking series was read most attentively and fruitfully not in Europe but in other parts of the Americas, where a collection of Spanish colonies and the single Portuguese one were pupating into nations and, like the United States, creating national lit eratures. They too, looking for autochthonous subjects, found the opu lent scenery and the original inhabitants sanctioned by the European discourse of the exotic and began to fashion from them a way of repre senting a non-European identity. Cooper showed that it could be done and was admired for it.1 His works were aligned with European exam ples of how to use exotic materials and seen as patterns for adapting a discourse of the exotic to the production of an American literature of nationality. The Cooper with whom other American literatures of nationality es tablished an intertextual relationship was strictly the creator of the Leather-stocking. Neither his sea novels nor those in which he conducts an acerbic argument with his contemporaries were taken as models. Certainly the choice in Notions of the Americansto assert national identity by opposing exoticism, its assumption that the power relation on which 1 According to Doris Sommer Cooper's "Latin-American heirs . reread and rewrote him" (Foundational Fictions, p. 52). The Argentinian Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, indeed, "copied" Cooper (p. 65). 186 The "Indian" Novels of Alencar 187 the exotic rests can be renegotiated through a shortcut that avoids it, does not enter the repertoire of these other literatures of nationality.