Collective Representation on the Tandridge District Local Plan – Issues and Approaches Regulation 18 Consultation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

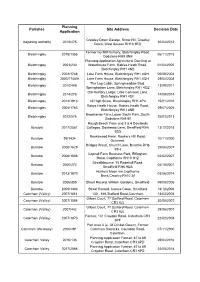

Parishes Planning Application Site Address Decision Date

Planning Parishes Site Address Decision Date Application Crawley Down Garage, Snow Hill, Crawley Adjoining Authority 2012/475 30/04/2012 Down, West Sussex RH10 3EQ Former Ivy Mill Nursery, Bletchingley Road, Bletchingley 2015/1358 06/11/2015 Godstone RH9 8NB Planning Application Agricultural Dwelling at Bletchingley 2003/230 Waterhouse Farm, Rabies Heath Road, 01/04/2005 Bletchingley RH1 4NB Bletchingley 2003/1748 Lake Farm House, Bletchingley RH1 4QH 05/08/2004 Bletchingley 2003/1748/A Lake Farm House, Bletchingley RH1 4QH 29/04/2008 The Log Cabin, Springmeadow Stud, Bletchingley 2010/459 13/09/2011 Springbottom Lane, Bletchingley RH1 4QZ Old Rectory Lodge, Little Common Lane, Bletchingley 2014/278 14/08/2014 Bletchingley RH1 4QF Bletchingley 2014/1913 46 High Street, Bletchingley RH1 4PA 15/01/2016 Rabys Heath House, Rabies Heath Road, Bletchingley 2004/1763 29/07/2005 Bletchingley RH1 4NB Brooklands Farm,Lower South Park,,South Bletchingley 2012/576 25/03/2013 Godstone,Rh9 8lf Rough Beech Farm and 3 & 4 Dowlands Burstow 2017/2581 Cottages, Dowlands Lane, Smallfield RH6 13/12/2018 9SD Rookswood Farm, Rookery Hill Road, Burstow 99/1434 10/11/2000 Outwood. Bridges Wood, Church Lane, Burstow RH6 Burstow 2006/1629 25/06/2007 9TH Cophall Farm Business Park, Effingham Burstow 2006/1808 02/02/2007 Road, Copthorne RH10 3HZ Streathbourne, 75 Redehall Road, Burstow 2000/272 04/10/2001 Smallfield RH6 9QA Hunters Moon Inn,Copthorne Burstow 2013/1870 03/06/2014 Bank,Crawley,Rh10 3jf Burstow 2006/805 Street Record, William Gardens, Smallfield 09/08/2006 Burstow 2005/1446 Street Record, Careys Close, Smallfield 18/12/2006 Caterham (Valley) 2007/1814 130 - 166,Stafford Road,Caterham 13/03/2008 Gilbert Court, 77 Stafford Road, Caterham Caterham (Valley) 2007/1088 30/08/2007 CR3 6JJ Gilbert Court, 77 Stafford Road, Caterham Caterham (Valley) 2007/442 28/06/2007 CR3 6JJ Former, 131 Croydon Road, Caterham CR3 Caterham (Valley) 2007/1870 22/02/2008 6PF Part Area 3 (e. -

January 2021 Minutes

Chelsham & Farleigh Parish Council The minutes of the virtual meeting over Zoom of the Parish Council of Chelsham & Farleigh held on Monday 4th January 2021 at 7:30pm Attendees: Cllr Jan Moore - Chairman Cllr Peter Cairns Cllr Lesley Brown Cllr Barbara Lincoln Cllr Neil Chambers Cllr Jeremy Pursehouse ( Parish & District Councillor) Cllr Celia Caulcott (District Councillor) Cllr Becky Rush (County Councillor) Mrs Maureen Gibbins - Parish Clerk & RFO ————————————————————————————————— M I N U T E S 1. Apologies for absence Cllr Nancy Marsh and District Cllr Simon Morrow 2. Declaration of Disclosable Pecuniary Interest by Councillors of personal pecuniary interests in matters on the agenda, the nature of any interests, and whether the member regards the interest to be prejudicial under the terms of the new Code of Conduct. Anyone with prejudicial interest must, unless an exception applies, or a dispensation has been issued, withdraw from the meeting. There was no specific declaration of interest although all the Councillors have an interest in the area due to living in the Parish 3. A period of fifteen minutes (including County and District Councillors reports) are available for the public to express a view or ask a question on relevant matters on the following agenda. 10 members of the public were in attendance of which 8 were observing the meeting and 1 spoke regarding the high speed fibre broadband and another the issues regarding the bridleway at Holt Wood. County Cllr Becky Rush - had a site meeting with residents prior to Christmas in relation to the highways issues regarding the crematorium. Cllr Rush is meeting with Highways Officers on 8th January raise the concerns and issues highlighted by resi- dents at the pre Christmas meeting. -

Chelsham & Farleigh Parish Council

CHELSHAM & FARLEIGH PARISH COUNCIL The minutes of the meeting of the Parish Council of Chelsham & Farleigh held at Farleigh Hall, Farleigh on 4th April 2016 PRESENT Bob Anderson Mike Webb Peter Cairns Tony Roberts David Marden Jeremy Pursehouse (Tandridge District Councillor) Michelle Richards (Clerk in attendance) The meeting opened at 8.03pm under the chairmanship of Bob Anderson Tony Adams - member of the public Mr Adams (who has just moved into Keepers Cottage on the Holt,wanted to highlight the planning application he will be submitting to TDC this week. Mr Adam’s plan is to convert the current wooden cabin into a 3 bed accommodation built of brick/block using the same footprint and outline and clad in shiplap effect plastic so the appear- ance remains unchanged . Mr Adam’s showed the plans to the councillors and Bob thanked him for coming to the meeting to discuss, before submitting to TDC. 1.Minutes of meeting dated 7th March previously circulated, were duly approved. 2.Apologies and reasons for absence - David H due to a meeting conflict and Alex due to a work commitment. 3.Declaration of Interest by Councillors In view of the proximity of Councillors homes in relation to the area and layout of the hamlets which make up Chelsham & Farleigh all Councillors declared a personal interest in the agenda items. 4. Matters Arising from Minutes None. 5. Planning To discuss any planning applications received Tandridge Gypsy & Traveller Accommodation Assessment - Bob asked the Parish Council to ratify his response to TDC, about the assessment. The Parish Council did so. -

Final Recommendations on the Future Electoral Arrangements for Tandridge in Surrey

LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS ON THE FUTURE ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR TANDRIDGE IN SURREY Report to the Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and the Regions September 1998 LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND This report sets out the Commission’s final recommendations on the electoral arrangements for Tandridge in Surrey. Members of the Commission are: Professor Malcolm Grant (Chairman) Helena Shovelton (Deputy Chairman) Peter Brokenshire Professor Michael Clarke Pamela Gordon Robin Gray Robert Hughes Barbara Stephens (Chief Executive) ©Crown Copyright 1998 Applications for reproduction should be made to: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Copyright Unit The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by The Local Government Commission for England with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G. This report is printed on recycled paper. ii LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CONTENTS page LETTER TO THE SECRETARY OF STATE v SUMMARY vii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 CURRENT ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS 3 3 DRAFT RECOMMENDATIONS 7 4 RESPONSES TO CONSULTATION 9 5 ANALYSIS AND FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS 11 6 NEXT STEPS 21 APPENDICES A Final Recommendations for Tandridge: Detailed Mapping 23 B Draft Recommendations for Tandridge (March 1998) 29 LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND iii iv LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND Local Government Commission for England September 1998 Dear Secretary of State On 2 September 1997 the Commission began a periodic electoral review of the district of Tandridge under the Local Government Act 1992. -

C&F September Minutes 2019 2

Chelsham and Farleigh Parish Council The minutes of the meeting of the Chelsham and Farleigh parish council held at the St Marys church hall Farleigh on 2nd September 2019. In attendance, Jan Moore – chair Lesley Brown – vice chair Nancy Marsh Barbara Lincoln Peter Cairns The meeting opened at 8.02pm under the chairmanship of Jan Moore. 1. Apologies for absence were received from –Michelle Richards – clerk illness. Jeremy Pursehouse. Annual leave. There were no other apologies received. The previous meetings minutes were agreed subject to the amendment in item 3 below as a true record and signed by the chair. 2. There were no declarations of interest. It was noted also that the Clerk also needs to fill in Declaration of Interest form. One member of the public arrived after the meeting opened. A local resident Mrs Elizabeth Gates. Mrs Gates requested that the parish council contact Surrey C.C. with regard to the overgrown hedge on both sides of the road from the Old Rectory Cottage right through to the farm buildings where the Farleigh Court Golf course side entrance meets the road. This applies to both sides of the road along this section. The hedge is a hindrance to both horse riders and larger vehicles due to it hanging down in the middle of the road. The old Moat is also in desperate need of attention. The Parish Council should write to Merton College who we believe are responsible for it and to highlight the condition requesting that they consider giving it some attention. 3. Amendment to previous minutes dated 1st July 2019. -

Open Space Strategy Consultation Statement

Open Space Strategy Consultation Statement Introduction This Consultation Statement sets out how Tandridge District Council engaged with partners, stakeholders and the community to develop and shape the Council’s Open Space Strategy. This Statement also sets out how information about the Strategy, along with details about the Strategy consultation, was publicised and made available to all. The consultation for the Open Space Strategy set out to establish the following points: 1. To obtain the views of those who participated in the consultation to clarify how they would like the Council to improve and manage open spaces across the district; 2. To seek the views of stakeholders for the strategic direction of the strategy, to identify opportunities to make links and to work jointly to deliver the actions identified in the strategy; 3. To bring to the fore any potential impacts arising from the draft Open Space Strategy on the protected characteristics identified in the Equality Act 2010. Consultation Process From June 2019 to September 2019, the Council met with individual parish councils to initially understand what concerned them in relation to their open spaces, what would they like to see improved, what they owned and what opportunities were available. The main points raised from these meetings are detailed in Appendix 2 of the Open Space Strategy. In July 2019, the Council conducted a residents’ survey which asked residents to comment on whether they used the parks and open spaces, how often they used them, what they used them for and what additional facilities they would like provided. The survey yielded 1,016 responses with a 41% response rate randomised sample of 2,500 residents. -

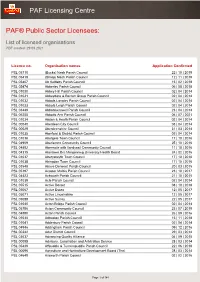

List of Licensed Organisations PDF Created: 29 09 2021

PAF Licensing Centre PAF® Public Sector Licensees: List of licensed organisations PDF created: 29 09 2021 Licence no. Organisation names Application Confirmed PSL 05710 (Bucks) Nash Parish Council 22 | 10 | 2019 PSL 05419 (Shrop) Nash Parish Council 12 | 11 | 2019 PSL 05407 Ab Kettleby Parish Council 15 | 02 | 2018 PSL 05474 Abberley Parish Council 06 | 08 | 2018 PSL 01030 Abbey Hill Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01031 Abbeydore & Bacton Group Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01032 Abbots Langley Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01033 Abbots Leigh Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 03449 Abbotskerswell Parish Council 23 | 04 | 2014 PSL 06255 Abbotts Ann Parish Council 06 | 07 | 2021 PSL 01034 Abdon & Heath Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 00040 Aberdeen City Council 03 | 04 | 2014 PSL 00029 Aberdeenshire Council 31 | 03 | 2014 PSL 01035 Aberford & District Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01036 Abergele Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04909 Aberlemno Community Council 25 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04892 Abermule with llandyssil Community Council 11 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04315 Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Board 24 | 02 | 2016 PSL 01037 Aberystwyth Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 01038 Abingdon Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 03548 Above Derwent Parish Council 20 | 03 | 2015 PSL 05197 Acaster Malbis Parish Council 23 | 10 | 2017 PSL 04423 Ackworth Parish Council 21 | 10 | 2015 PSL 01039 Acle Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 05515 Active Dorset 08 | 10 | 2018 PSL 05067 Active Essex 12 | 05 | 2017 PSL 05071 Active Lincolnshire 12 | 05 -

61A CROYDON ROAD, CATERHAM CR3 6PD 01883 348877 8 the Caterham and District Independent July 2011 01883 346641

CATERHAM AUTO CataxLtd REPAIRS Est. 1946 All Mechanical & Body Repairs Caterham’s longest established taxi Servicing, MOTs company Minis a Speciality CATERHAM OFFICE Roffes Lane, Caterham Surrey CR3 5PT 01883 345151 01883 348748 www.caterhamtaxis.com No. 62 July 2011 CIRCULATION: 22,000 ESTABLISHED 2006 FREE ‘Perfect’ setting for Classic Summer Evening Grounds of David Gold’s house, ‘The Chalet’, in full bloom ready for next week’s open air concert. The groundsman and garden- dridge Community Fund first classical musicians. It will ers at ‘The Chalet’ in Tupwood had the idea for a concert look amazing when the stage Lane, Caterham, have been when Mr Gold hosted an has been erected against the working hard to ensure the ‘Open Garden’ event for the backdrop of the Victorian lawns and flowerbeds are in Fund last year. house.” tip-top condition ready for the Jeremy said: “Mr Gold really Songwriter and founder of open-air classical concert tak- liked the idea because he said the Orpheus Centre in God- ing place there on Saturday it will give the public the stone, Richard Stilgoe will be 2nd July. chance to see his garden in the compere for the evening. The concert, the first of its high summer, instead of in The concert will feature tal- kind in Caterham, is being the spring when he normally ented musicians playing held to raise funds for the opens the garden for charity. music by Elgar, Ravel, Tandridge Community Fund He agreed that the sweeping Chopin, Gershwin, Beethoven local charity, that was set up lawns by the terrace will and more. -

A RDR Spring 2001

Common Worship THE Services and Prayers for the Church of England Beautifully bound in a range of attractive colours and READER printed in black and red ink on a high quality cream paper,this standard edition is not only a treasure to start using immediately but a personal memento that will go on giving pleasure for years. Recommended retail prices range from £15 to £50. Available from all good bookshops. For more details of Common Worship, please see www.commonworship.com Official and complementary materials available now Official and complementary materials available THE HOUSE OF VANHEEMS LTD Established 1793 St Martin Vestment Ltd READERS’ ROBES Lutton, Near Spalding, Lincs PE12 9LR Excellent quality, cut and tailoring at the Tel/Fax 01406 362386 most reasonable prices or over 25 years our workshop has been Double breasted cassock producing individually made church regalia £115.00 F for churches and cathedrals at home and abroad. Ripon Surplice £48.00 The firm remains in the hands of a clergy family but is managed by Mrs Dorothea Butcher who Reader Blue Scarf will be pleased to discuss £39.00 your requirements. Send for details and D Please telephone or fabric samples. E C F write for further details B and measurement form Cassocks for Readers G L are supplied at prices A Broomfield Works ranging from £71 to Broomfield Place considerably more. Ealing London W13 9LB Tel: 020-8567-7885 THE READER In all things thee to see Spring 2001 Volume 98 No.1 £1.75 Faith House Bookshop BOOKS 7 Tufton Street London SW1P 3QN CDS Tel 020 7222 6952 Fax 020 7976 7180 ICONS DEVOTIONAL Website: www.faithhousebookshop.co.uk MATERIALS e-mail: [email protected] Lent and Easter We carry a wide range of Lent courses, Paschal Candles, Palm Crosses and Church Requisites.We also stock Icons that show the major events of the Easter story. -

Tandridge District Council - Buildings of Character (November 2013)

Tandridge District Council - Buildings of Character (November 2013) Although local Buildings of Character cannot be given the statutory protection afforded to listed buildings, the Council will seek to keep them wherever possible. The list can never be definitive as buildings may be added from time to time and the Council reserves the right to add to this list. Many of the Buildings of Character were added to the list before the Council adopted criteria for identifying such buildings and most of the buildings have not been reviewed against the criteria. Therefore if an owner has concerns about the inclusion of a building a request can be made to the Council to review it against the criteria. Multiple entries on the list can occur where there is more than one building on a property, for example a group of farm buildings. XREF YREF Address WARD NAME 531244.80 152962.60 Warwick Wold Farm Oakwood Road Merstham Redhill Bletchingley and Nutfield 532832.90 153005.70 Hermitage Hextalls Lane Bletchingley Redhill Bletchingley and Nutfield 532585.85 153668.95 Arthurs Seat White Hill Caterham Bletchingley and Nutfield 531632.45 151198.35 Cockley Cottage Big Common Lane Bletchingley Redhill Bletchingley and Nutfield 531634.90 151739.80 Little Pendell Pendell Mews Pendell Road Bletchingley Redhill Bletchingley and Nutfield 530231.75 149959.75 1 Priory Farm Cottages Sandy Lane South Nutfield Redhill Bletchingley and Nutfield 530226.00 149953.70 2 Priory Farm Cottages Sandy Lane South Nutfield Redhill Bletchingley and Nutfield 530107.75 149892.50 Little -

Official Guide & Street Plan 2015-2016

TAN_308206 FC Spread_spine.qxd 1/12/14 15:07 Page 1 TANDRIDGE TANDRIDGE Official Guide & Street Plan 2015-2016 Official Guide & Street TANDRIDGE Official Guide & Street Plan 2015-2016 TAN_308206 FC Spread_spine.qxd 1/12/14 15:07 Page 2 HOUSE PLANS DRAWN for your NEW BUILD EXTENSION, ROOF ROOM ANNEX, KITCHEN, EXTENSION, GARDEN STUDIO WHY MOVE WHEN YOU CAN CREATE SPACE & ADD VALUE TO YOUR EXISTING PROPERTY? We are a local architect practice based in Warlingham and provide design and planning services to obtain planning permission for domestic building projects, including new builds, home extensions and garden outbuildings. TREE FELLING, FENCING Contact us for a FREE visit and consultation to discuss your project. HEDGE CUTTING & DITCHING, Bob Mewies CHARTERED ENGINEER 07767 690331 SPRAYING, Forge Cottage, 55 Farleigh Road, Warlingham, Surrey CR6 9EJ SPORTS PITCH MAINTENANCE GROUND BREAKING Architectural Design Services OVER SEEDING www.bobmewies.com HARROW AND ROLLING, SLITTING/AERATING FERTILISING Best Buyer of any vehicle from £500 - £50,000 Part Exchanging Your Car? THE COTTAGE Been offered a poor trade in price? FRYERN FARM Why not give us a try? ROOK LANE We will try to improve your trade price. CHALDON CATERHAM Fast, friendly, professional service SURREY CR3 5AA money paid, same day instant bank transfer. Tel: CATERHAM (01883) 347881 Fax: CATERHAM (01883) 347443 01883 621348 www.paulmewies.co.uk 07970 600555 Email: [email protected] Mewies Ltd I Unit 1 I 79 Farleigh Road I Warlingham I Surrey CR6 9EJ 3034537 3033881 B/308206/11/14/ADV` -

Warlingham Community Directory 'Our Village'

Warlingham Community Directory ‘Our Village’ This Warlingham Community Directory contains essential information for those living in and around Warlingham. We believe it would be especially useful for newcomers and help them to settle in and become part of village life. It is set out alphabetically under main headings followed by individual listings; collectively these offer you, the reader, a unique reference point to come back to whenever you need information. We try to cover most things but have to use some discretion. Generally we include organizations based physically in the Warlingham area, or else nearby if they are regularly used by Warlingham residents. Thank you to the many volunteers who have been involved in preparing this community resource and also to Parish News, its sister publication, for financing this edition. Entries have been checked according to the General Data Protection Regulation and we thank all those concerned for their patience and support. If there are errors, we apologise, and ask you to send them to the editor, [email protected]. Please acknowledge the Warlingham Community Directory as the source. Accident Services Minor Injuries Unit (for over 18's) 01883 837500 Caterham Dene Hospital, Church Road, Caterham CR3 5RA NHS Choices (Accident & Emergency) www.nhs.uk Minor 111 Urgent 999 Alcoholics Anonymous www.alcoholics-anonymous.org.uk 0800 9177 650 [email protected] Allotments Allotments - Tandridge District Council 01883 722000 www.tandridge.gov.uk The Warlingham Allotment Garden Association Contact: Derek Butler 01883 623618 St Christopher’s Allotments Contact: Revd Michelle Edmonds 01883 623011 1 Amateur Dramatics ATG Drama Group www.atgdramagroup.co.uk Acting on stage or performing any of the vital off-stage roles Contact: Nicola Newman [email protected] 07949 024824 Arts and Crafts A Crafty Club Mission Room, Chapel Road, Warlingham Fri 10am – 1pm.