The Most Daring Act of the Age—Principles for Naval Irregular War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crucial Victory on Lake Champlain – “9/11” 1814 America’S Second War for Independence (1812 – 1815)

Crucial Victory on Lake Champlain – “9/11” 1814 America’s Second War for Independence (1812 – 1815) The War of 1812, also known as America’s Second War for Independence, was a contest to see if a free, republican form of government could survive. The Irish in America again rallied to the colors – the rapid fortification, by the Irish, of the Battery in New York City being but one example. Thomas Addis Emmet raised the Irish Republican Greens, which participated with the US Army for the duration of the war, including in the 1813 invasion of Canada. [See: Washington’s Irish by Derek Warfield.] England does not recognize expatriation, i.e., that someone born in the United Kingdom could ever renounce being a “British subject” and acquire American (or any other) citizenship. This resulted in the impressment of American merchant seamen into the Royal Navy, one of the causes of the war. During the course of the war it also gave rise to an English threat to hang any captured Irish-born members of the American forces. American General Winfield Scott countered by promising to hang two English prisoners of war for every Irishman hanged. No one was hanged. In essence, England’s war aims in North America during 1812-1815, were similar to those of 1775-1783, but with a strategy based on lessons learned from the former conflict. After the defeat of Napoleon in 1814, the Duke of Wellington sent sixteen of his best veteran infantry regiments, plus cavalry and artillery, to North America to attempt the partitioning of the United States by driving down the Champlain and Hudson Valleys, as intended by “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne in 1777, to cut off New England from the rest of the country. -

Symbolism of Commander Isaac Hull's

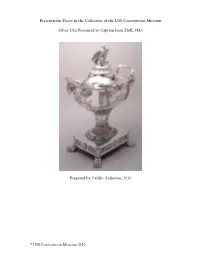

Presentation Pieces in the Collection of the USS Constitution Museum Silver Urn Presented to Captain Isaac Hull, 1813 Prepared by Caitlin Anderson, 2010 © USS Constitution Museum 2010 What is it? [Silver urn presented to Capt. Isaac Hull. Thomas Fletcher & Sidney Gardiner. Philadelphia, 1813. Private Collection.](1787–1827) Silver; h. 29 1/2 When is it from? © USS Constitution Museum 2010 1813 Physical Characteristics: The urn (known as a vase when it was made)1 is 29.5 inches high, 22 inches wide, and 12 inches deep. It is made entirely of sterling silver. The workmanship exhibits a variety of techniques, including cast, applied, incised, chased, repoussé (hammered from behind), embossed, and engraved decorations.2 Its overall form is that of a Greek ceremonial urn, and it is decorated with various classical motifs, an engraved scene of the battle between the USS Constitution and the HMS Guerriere, and an inscription reading: The Citizens of Philadelphia, at a meeting convened on the 5th of Septr. 1812, voted/ this Urn, to be presented in their name to CAPTAIN ISAAC HULL, Commander of the/ United States Frigate Constitution, as a testimonial of their sense of his distinguished/ gallantry and conduct, in bringing to action, and subduing the British Frigate Guerriere,/ on the 19th day of August 1812, and of the eminent service he has rendered to his/ Country, by achieving, in the first naval conflict of the war, a most signal and decisive/ victory, over a foe that had till then challenged an unrivalled superiority on the/ ocean, and thus establishing the claim of our Navy to the affection and confidence/ of the Nation/ Engraved by W. -

1 Overview of USS Constitution Re-Builds & Restorations USS

Overview of USS Constitution Re-builds & Restorations USS Constitution has undergone numerous “re-builds”, “re-fits”, “over hauls”, or “restorations” throughout her more than 218-year career. As early as 1801, she received repairs after her first sortie to the Caribbean during the Quasi-War with France. In 1803, six years after her launch, she was hove-down in Boston at May’s Wharf to have her underwater copper sheathing replaced prior to sailing to the Mediterranean as Commodore Edward Preble’s flagship in the Barbary War. In 1819, Isaac Hull, who had served aboard USS Constitution as a young lieutenant during the Quasi-War and then as her first War of 1812 captain, wrote to Stephen Decatur: “…[Constitution had received] a thorough repair…about eight years after she was built – every beam in her was new, and all the ceilings under the orlops were found rotten, and her plank outside from the water’s edge to the Gunwale were taken off and new put on.”1 Storms, battle, and accidents all contributed to the general deterioration of the ship, alongside the natural decay of her wooden structure, hemp rigging, and flax sails. The damage that she received after her War of 1812 battles with HMS Guerriere and HMS Java, to her masts and yards, rigging and sails, and her hull was repaired in the Charlestown Navy Yard. Details of the repair work can be found in RG 217, “4th Auditor’s Settled Accounts, National Archives”. Constitution’s overhaul of 1820-1821, just prior to her return to the Mediterranean, saw the Charlestown Navy Yard carpenters digging shot out of her hull, remnants left over from her dramatic 1815 battle against HMS Cyane and HMS Levant. -

USS Ranger CV-61

25 IK USS Ranger CV-61 John Paul Jones In ITU, the launching of an American Con- tinental frigate christened Ranger, set into motion a series of events that would, today, astound the crew and commander of the Revolutionary War-era vessel. Today, over 200 years later, our mighty war- ship dwarfs her namesake in size and power, but matches, without a doubt, the sense of pride and dedication in the knowledge that she has and con- tinues to serve her nation to the utmost of her abilities. Therefore, on this, our Ranger's 25th anniver- sary, it is only fitting that the man who began the great tradition of Ranger speak in her behalf. Our featured speaker for today's program is Capt. John Paul Jones of the Continental Navy. RANGER HISTORY In 1776, the Continental Congress set forth a used as a lookout vessel in Chesapeake Bay dur- declaration that, in its summation, stated the de- ing the war of 1812. sire of it) members and their constituents to be- The third Ranger, a brigantine of 14 guns, come a free nation. served also during ihe War of 1812 with Cmdr, Our country's fore-fathers, however, were well Isaac Chauncey's squadron. aware that such freedom would only be won after The fourth Ranger was of a new design whose a fierce war for independence. They created for- iron hull and steam-powered engines heralded the ces they hoped would be capable of securing for Navy's emergence into the 20th century. This the new-born nation the independence she longed Ranger was, perhaps, the first to truly show Am- for. -

![1913-06-20, [P ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7842/1913-06-20-p-327842.webp)

1913-06-20, [P ]

— 1 WEATHER- F For Delaware! Overcast, ij Circulation Î4,349| I warm; probably thunder- I; Yesterday »bowers tonight or Satur* 11 day; light south wind The Evening Journal GUARANTEED te ^TWENTY-SIXTH YEAR-NO. 28 WILMINGTON. DELAWARE, FRIDAY. JUNE 20, 1913 16 PAGES ► ONE CENT STATES MUSI O.M.D. CAMP SEN. DUPONT Happy? Certainly! Mme. Rappold, ... ah . lfmnM Prima Donna, Gets Divorce and $150,000 FOR RECEIVER ENFORCE WEBB IN HONOR OF LAUDSPLÄNTO Will Wed Tenor of Early Dreams STREETS; NONE ASKED FOR LIQUOR LAW MACDONOUGH BOOM CITY FOR PlAYFIELD LUMBER CO. Attorney General M’Reynolds Governor Calls State Defend Regrets That He Cannot At / Council Defeats Mr. Haney's Philadelphians Seek Order Gives Interpretation of ers to Field Instruction tend Chamber of Com Tenth Ward Improvement From Local Court After Conviction of Inter Anti-Shipment Act July 19-26 « merce Dinner to Plan by One Vote v national Heads HO FEDERAL PENALTY* AND FIRST GENERAL Editors SOLON PLEADS FOR CHANCELLOR ISSUES STATES HAVE JURISDICTION ORDER IS ISSUED SEES MUCH GOOD IN TOTS’ OUTING PLACE RULE IN THE CASK Many Wllralngtonlsns are Intereat- Oeneral orders were issued today CLOSER PENINSULA TIES City Council by -.unanimous vote K In the announcement fromWashlag- by command of Governor Charles R. last night passed the ordinance pro Chancellor Charles M. Curtis has Is n yesterday that the Webb-Ke.iyon Miller, through adjutant General 1. ! Regretting that he will be unable, viding a bond isiuo of $150.000 for sued a rule returnable on Monday, Maw, forbidding interstate shipments Pusey Wiokersham, chief of staff, for jbecause of official duties, to attend July 20, In the case of Coverly-Haakina •f liquor Into “dry” States Is not a street ,«nd sewer Improvements, and et al„ vs. -

Thomas Wilkey Journal on Board the U.S.S. Delaware LCP.Wilkey

Thomas Wilkey journal on board the U.S.S. Delaware LCP.Wilkey This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit September 22, 2014 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Library Company of Philadelphia 2012 March 10 Thomas Wilkey journal on board the U.S.S. Delaware LCP.Wilkey Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical/Historical note.......................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents note............................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................5 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................5 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 7 - Page 2 - Thomas Wilkey journal on board the U.S.S. Delaware LCP.Wilkey Summary Information Repository Library Company of Philadelphia Creator Wilkey, Thomas Title Thomas Wilkey journal -

Chronology of the American Revolution

INTRODUCTION One of the missions of The Friends of Valley Forge Park is the promotion of our historical heritage so that the spirit of what took place over two hundred years ago continues to inspire both current and future generations of all people. It is with great pleasure and satisfaction that we are able to offer to the public this chronology of events of The American Revolution. While a simple listing of facts, it is the hope that it will instill in some the desire to dig a little deeper into the fascinating stories underlying the events presented. The following pages were compiled over a three year period with text taken from many sources, including the internet, reference books, tapes and many other available resources. A bibliography of source material is listed at the end of the book. This publication is the result of the dedication, time and effort of Mr. Frank Resavy, a long time volunteer at Valley Forge National Historical Park and a member of The Friends of Valley Forge Park. As with most efforts of this magnitude, a little help from friends is invaluable. Frank and The Friends are enormously grateful for the generous support that he received from the staff and volunteers at Valley Forge National Park as well as the education committee of The Friends of Valley Forge Park. Don R Naimoli Chairman The Friends of Valley Forge Park ************** The Friends of Valley Forge Park, through and with its members, seeks to: Preserve…the past Conserve…for the future Enjoy…today Please join with us and help share in the stewardship of Valley Forge National Park. -

The 1812 Streets of Cambridgeport

The 1812 Streets of Cambridgeport The Last Battle of the Revolution Less than a quarter of a century after the close of the American Revolution, Great Britain and the United States were again in conflict. Britain and her allies were engaged in a long war with Napoleonic France. The shipping-related industries of the neutral United States benefited hugely, conducting trade with both sides. Hundreds of ships, built in yards on America’s Atlantic coast and manned by American sailors, carried goods, including foodstuffs and raw materials, to Europe and the West Indies. Merchants and farmers alike reaped the profits. In Cambridge, men made plans to profit from this brisk trade. “[T]he soaring hopes of expansionist-minded promoters and speculators in Cambridge were based solidly on the assumption that the economic future of Cambridge rested on its potential as a shipping center.” The very name, Cambridgeport, reflected “the expectation that several miles of waterfront could be developed into a port with an intricate system of canals.” In January 1805, Congress designated Cambridge as a “port of delivery” and “canal dredging began [and] prices of dock lots soared." [1] Judge Francis Dana, a lawyer, diplomat, and Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, was one of the primary investors in the development of Cambridgeport. He and his large family lived in a handsome mansion on what is now Dana Hill. Dana lost heavily when Jefferson declared an embargo in 1807. Britain and France objected to America’s commercial relationship with their respective enemies and took steps to curtail trade with the United States. -

AH197804.Pdf

P "I MAGAZINE OF THE U.S. NAVY -55th YEAR OF PUBLICATION APRIL 1978 NUMBER 735 Features 4 DEPUTYCOMPTROLLER TALKS PAY An Interview with RADMJames R. Ahern 8 MUGS AWAY! Darts have taken over in Sigonella 13 FIRST AMERICAN ARTIST IN ANTARCTICA The works of Arthur E. Beaumont Page 22 22 QUIET PROFESSIONALISM IN A SEA OF HASTE A busy weekend in a naval hospital's emergency room 28 A LOOK AT DIEGO GARCIA Construction and life at the IndianOcean base 32 TO ALL SAILORSWHEREVER YE MAY BE Certificates document one's Navy travels 38 RIVERINE VETS Reservists go over lessons learned in war 44 FOR THE NAVY BUFF More lore on life in the Navy Departments 2 Currents 17 Bearings Pane 28 27 MCPON 36 Grains of Salt 48 BuoyMail Covers Front: One of the works of Navy Combat Artist Arthur E. Beaumont, jirst American artist to execute paintings in Antarctica. See page 13. Left: Gunner's Mate Seaman David Jutz greases the gun barrel chase of one of the two five- inch gun mounts on the destroyer USS Hull (DD 945). Chiefof Naval Operations: Admiral James L. Holloway Ill Staff:LT Bill Ray Chief of Information: Rear Admiral David M. Cooney JOC Dan Guzman Dir. Print Media Div. (NIRA): Lieutenant John Alexander DM1 Ed Markharn Editor: JohnEditor: F. Coleman JOIAtchison Jerry News Editor: Joanne E. Dumene JOI (SS) Pete Sundberg ProductionEditor: Lieutenant ZakemJeff PH 1 TerryMitchell Layout Editor: E. L. Fast JO2 Davida Matthews Art Editor: Michael Tuffli J02 Dan Wheeler Research Editor: Catherine D. FellowsEdwardJenkins Elaine McNeil Page 38 President’s Pay Commission Makes Final Recommendations 0 The President’s Commission on Military Compensation recently decided on its final recommendations to President Carter for the reform of the military pay and benefits system. -

An Incomplete History of the USS FISKE (DD/DDR 842)

An Incomplete History of the USS FISKE (DD/DDR 842) For The Fiske Association Prepared by R. C. Mabe – Association Historian October 1999 Edited & revised by G. E. Beyer – Association Historian September 2007 Introduction The USS FISKE was a Gearing Class destroyer, the last of the World War II design destroyers. She served in the US Navy from 1945 until 1980 and was subsequently transferred to the Turkish Navy where she served as the TCG Piyale Pasa (D350). The former FISKE was heavily damaged in 1996 when she ran aground and was scrapped in early 1999. Altogether the FISKE served two navies for over 54 years. I am titling this report as an „Incomplete History of the USS Fiske DD/DDR 842‟ for the simple reason that it not complete. I am continuing to try and fill the gaps and inconsistencies to the best of my ability. Any help in this effort will be appreciated. The Soul of a Ship Now, some say that men make a ship and her fame As she goes on her way down the sea: That the crew which first man her will give her a name – Good, bad, or whatever may be. Those coming after fall in line And carry the tradition along – If the spirit was good, it will always be fine – If bad, it will always be wrong/ The soul of a ship is a marvelous thing. Not made of its wood or its steel, But fashioned of mem‟ries and songs that men sing, And fed by the passions men feel. -

Alumni News & Notes

et al.: Alumni News & Notes and hosted many Homecoming Weekend here are students who maintain strong activities. "The goals of SUSA include pro T ties to Syracuse University after they viding leadership roles for students, pro graduate. Then there are students like viding career and mentoring opportuni Naomi Marcus 'o2. Just beginning her col ties for students, connecting and network lege career, she has already established a ing with Syracuse alumni, and maintain bond with the SU alumni community. ing traditions and a sense of pride in Marcus is an active member of the Syra Syracuse University," says Setek. cuse University Student Alumni Associa Danie Moss '99 says taking an active tion (SUSA}, a student volunteer organiza role in Homecoming Weekend was a mile tion sponsored by the Office of Alumni Re stone for SUSA. She and past SUSA presi lations that serves as a link between students dent Kristin Kuntz '99 saw it as a good way and the University's 22o,ooo alumni. to promote the organization. "Home For Marcus and her fellow student vol coming is a great opportunity for us to unteers, SUSA's appeal lies in its ability to interact with alumni," Moss says. "People bridge generations. "It sounded like a dif don't always realize how much they can ferent kind of organization," Marcus says. learn from other generations, so an organi "Alumni share their experiences with us, zation like this is mutually beneficial." WITH GRATITUDE AND RESPECT and we keep them up-to-date on what's Senior Alison Nathan has been pleas "Thank you"- two simple words that going on here right now. -

Congressional Gold Medals: Background, Legislative Process, and Issues for Congress

Congressional Gold Medals: Background, Legislative Process, and Issues for Congress Updated April 8, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45101 Congressional Gold Medals: Background, Legislative Process, and Issues for Congress Summary Senators and Representatives are frequently asked to support or sponsor proposals recognizing historic events and outstanding achievements by individuals or institutions. Among the various forms of recognition that Congress bestows, the Congressional Gold Medal is often considered the most distinguished. Through this venerable tradition—the occasional commissioning of individually struck gold medals in its name—Congress has expressed public gratitude on behalf of the nation for distinguished contributions for more than two centuries. Since 1776, this award, which initially was bestowed on military leaders, has also been given to such diverse individuals as Sir Winston Churchill and Bob Hope, George Washington and Robert Frost, Joe Louis and Mother Teresa of Calcutta. Congressional gold medal legislation generally has a specific format. Once a gold medal is authorized, it follows a specified process for design, minting, and presentation. This process includes consultation and recommendations by the Citizens Coinage Advisory Commission (CCAC) and the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts (CFA), pursuant to any statutory instructions, before the Secretary of the Treasury makes the final decision on a gold medal’s design. Once the medal has been struck, a ceremony will often be scheduled to formally award the medal to the recipient. In recent years, the number of gold medals awarded has increased, and some have expressed interest in examining the gold medal authorization and awarding process. Should Congress want to make such changes, several individual and institutional options might be available.