Final Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1Er Février 2015 — 15 H Salle De Concert Bourgie Prixopus.Qc.Ca

e 18 GALA1er février 2015 — 15 h Salle de concert Bourgie prixOpus.qc.ca LE CONSEIL QUÉBÉCOIS DE LA MUSIQUE VOUS SOUHAITE LA BIENVENUE À LA DIX-HUITIÈME ÉDITION DU GALA DES PRIX OPUS 14 h : accueil 15 h : remise des prix 17 h 30 : réception à la Galerie des bronzes, pavillon Michal et Renata Hornstein du Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal Écoutez l’émission spéciale consacrée au dix-huitième gala des prix Opus, animée par Katerine Verebely le lundi 2 février 2015 à 20 h sur les ondes d’ICI Musique (100,7 FM à Montréal) dans le cadre des Soirées classiques. Réalisation : Michèle Patry La Fondation Arte Musica offre ses félicitations à tous les finalistes et aux lauréats des prix Opus de l’an 18. La Fondation est fière de contribuer à l’excellence du milieu musical québécois par la production et la diffusion de concerts et d’activités éducatives, à la croisée des arts. Au nom de toute l’équipe du Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal et de la Fondation Arte Musica, je vous souhaite un excellent gala ! Isolde Lagacé Directrice générale et artistique sallebourgie.ca 514-285-2000 # 4 Soyez les bienvenus à cette 18e édition du gala des prix Opus. Votre fête de la musique. Un événement devenu incontournable au fil des ans ! Le gala des prix Opus est l’occasion annuelle de célébrer l’excellence du travail des interprètes, compositeurs, créateurs, auteurs et diffuseurs. Tout au long de la saison 2013-2014, ces artistes ont mis leur talent, leur créativité et leur ténacité au service de la musique de concert. -

Dossier Ensemble Paramirabo

Mot du directeur artistique Le mandat artistique de l’organisme Ensemble Paramirabo est de se présenter comme une voix pour la diffusion de la musique d’aujourd’hui et pour la promotion des compositeurs émergents. Ses membres travaillent de façon à faciliter l’accessibilité et la compréhension de la musique contemporaine auprès de tous les publics et de tous les milieux et se consacrent à la redynamisation du concert grâce à une programmation inédite. L’organisme ne se limite pas à un répertoire strict. Il touche autant à des œuvres de répertoire qu’à la musique actuelle qu’elle soit écrite, improvisée ou électroacoustique. Il fait appel à des musiciens et des artistes de la relève montréalaise afin de concrétiser ses projets et de combler les postes dus aux exigences instrumentales des œuvres présentées. La programmation reflète ce désir d’élargir les horizons et les expériences des auditeurs de nos concerts en favorisant la nouveauté, l’expérimentation et le risque. Nous avons un penchant pour les programmes qui tournent autour d’un thème ou qui offrent plusieurs points de vue divergents sur un même concept. Nous aimons également présenter des projets en collaborations avec des artistes issus d’autres domaines d’art qui amènent de nouvelles explorations et découvertes, citons en exemple les programmes cabarets ou théâtrales tel que nos productions THE CRAZIES! ou À chaque ventre son monstre (gagnant du Prix Opus - Création de l’année 2018). Dans les dernières années, nous avons fait un effort majeur pour créer des projets artistiques qui agissent comme un pont culturel avec des milieux différents. -

Download the TSO Commissions History

Commissions Première Composer Title They do not shimmer like the dry grasses on the hills, or January 16, 2019 Emilie LeBel the leaves on the trees March 10, 2018 Gary Kulesha Double Concerto January 25, 2018 John Estacio Trumpet Concerto [co-commission] In Excelsis Gloria (After the Huron Carol): Sesquie for December 12, 2017 John McPherson Canada’s 150th [co-commmission] The Talk of the Town: Sesquie for Canada’s 150th December 6, 2017 Andrew Ager [co-commission] December 5, 2017 Laura Pettigrew Dòchas: Sesquie for Canada’s 150th [co-commission] November 25, 2017 Abigail Richardson-Schulte Sesquie for Canada’s 150th (interim title) [co-commission] Just Keep Paddling: Sesquie for Canada’s 150th November 23, 2017 Tobin Stokes [co-commission] November 11, 2017 Jordan Pal Sesquie for Canada’s 150th (interim title) [co-commission] November 9, 2017 Julien Bilodeau Sesquie for Canada’s 150th (interim title) [co-commission] November 3, 2017 Daniel Janke Small Song: Sesquie for Canada’s 150th [co-commission] October 21, 2017 Nicolas Gilbert UP!: Sesquie for Canada’s 150th [co-commission] Howard Shore/text by October 19, 2017 New Work for Mezzo-soprano and Orchestra Elizabeth Cottnoir October 19, 2017 John Abram Start: Sesquie for Canada’s 150th [co-commission] October 7, 2017 Eliot Britton Adizokan October 7, 2017 Carmen Braden Blood Echo: Sesquie for Canada’s 150th [co-commission] October 3, 2017 Darren Fung Toboggan!: Sesquie for Canada’s 150th [co-commission] Buzzer Beater: Sesquie for Canada’s 150th September 28, 2017 Jared Miller [co-commission] -

Jules Léger Prize | Prix Jules-Léger

Jules Léger Prize | Prix Jules-Léger Year/Année Laureates/Lauréats 2020 Kelly-Marie Murphy (Ottawa, ON) Coffee Will be Served in the Living Room (2018) 2019 Alec Hall (New York, NY) Vertigo (2018) 2018 Brian Current (Toronto, ON) Shout, Sisyphus, Flock 2017 Gabriel Turgeon-Dharmoo (Montréal, QC) Wanmansho 2016 Cassandra Miller (Victoria, BC) About Bach 2015 2015 Pierre Tremblay (Huddersfield, UK) Les pâleurs de la lune (2013-14) 2014 Thierry Tidrow (Ottawa, ON) Au fond du Cloître humide 2013 Nicole Lizée (Lachine, QC) White Label Experiment 2012 Zosha Di Castri (New York, NY) Cortège 2011 Cassandra Miller (Montréal, QC) Bel Canto 2010 Justin Christensen (Langley, BC) The Failures of Marsyas 2009 Jimmie LeBlanc (Brossard, QC) L’Espace intérieur du monde 2008 Analia Llugdar (Montréal, QC) Que sommes-nous 2007 Chris Paul Harman (Montréal, QC) Postludio a rovescio 2006 James Rolfe (Toronto, ON) raW 2005 Linda Catlin Smith (Toronto, ON) Garland 2004 Patrick Saint-Denis (Charlebourg, QC) Les dits de Victoire 2003 Éric Morin (Québec, QC) D’un château l’autre 2002 Yannick Plamondon, (Québec, QC) Autoportrait sur Times Square 2001 Chris Paul Harman (Toronto, ON) Amerika Canada Council for the Arts | Conseil des arts du Canada 1-800-263-5588 | canadacouncil.ca | conseildesarts.ca 2000 André Ristic (Montréal, QC) Catalogue 1 (bombes occidentales) 1999 Alexina Louie (Toronto, ON) Nightfall 1998 Michael Oesterle (Montréal, QC) Reprise 1997 Omar Daniel (Toronto, ON) Zwei Lieder nach Rilke 1996 Christos Hatzis (Toronto, ON) Erotikos Logos 1995 John Burke (Toronto, ON) String Quartet 1994 Peter Paul Koprowski (London, ON) Woodwind Quintet 1993 Bruce Mather (Montréal, QC) YQUEM 1992 John Rea (Outremont, QC) Objets perdus 1991 Donald Steven (Montréal, QC) In the Land of Pure Delight 1989 Peter Paul Koprowski (London, ON) Sonnet for Laura 1988 Michael Colgrass (Toronto, ON) Strangers: Irreconcilable Variations for Clarinet, Viola and Piano 1987 Denys Bouliane (Montréal, QC) À propos.. -

August 14–18, 2018 Presented by the Earle Brown Music Foundation Charitable Trust the Dimenna Center for Classical Music | 450 W 37Th Street, New York, NY Contents

TIME:SPANS 2018 Mary Flagler Cary Hall is located at the DiMenna Center for Classical Music, 450 W 37th St, New York, NY 10018 Individual tickets: $20 / $10 (student discount) : brownpapertickets.com/event/3445666 TIME SPANS Festival pass: 5 concerts | $50 brownpapertickets.com/event/3445216 Presented by The Earle Brown Music Foundation Charitable Trust 2018 earle-brown.org timespans.org The following artworks are reproduced in this brochure with permission, as follows. Frontispiece: Hiroshi Sugimoto, Paramount Theater, Newark, “On the Beach,” 2015. Courtesy Sugimoto Studio, NY. Page 14–15: Rirkrit Tiravanija, Untitled 2008–2011 (the map of the land of feeling). Installation view of the exhibition, Print/Out, February 19–May 14, 2012. Digital Image ©MoMA/Licensed by SCALA/ Art Resource, NY. Page 25: ©Ellsworth Kelly, Brushstrokes Cut into Forty-Nine Squares and Arranged by Chance, 1951. Cut-and-pasted paper and ink, 13 ¾ x 14 inches. Purchased with funds given by Agnes Gund. Digital Image © MoMA/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY. Page 28: ©Ellsworth Kelly, Broadway, 1958. Oil on canvas, 78 x 69 ½ inches. Presented by E. J. Power through the Friends of the Tate Gallery, 1962. ©Tate, London/Art Resource, NY. A Contemporary Music Festival August 14–18, 2018 Presented by The Earle Brown Music Foundation Charitable Trust The DiMenna Center for Classical Music | 450 W 37th Street, New York, NY Contents 4 Introduction 6 August 14, 2018, at 8 pm Bozzini Quartet Cassandra Miller, Linda Catlin Smith Mary Flagler Cary Hall 10 August 15, 2018, at -

Rapport Annuel 2012

Rapport annuel 2012 AU QUÉBEC 2 ESPACE KENDERGI Photo : Magalie Dagenais Un espace de diffusion Projections sur écran - Conférences - Concerts - Ateliers de formation Un lieu de consultation - plus de 20,000 documents Un lieu unique en mémoire d’une grande ambassadrice de nos compositeurs : Maryvonne Kendergi 3 TABLE DES MATIÈRES Conseil d’administration . 4 À propos du CMC Québec . 5 Mot de la directrice . 6 Mot du président . 7 Compositeurs agréés . 8 Membres honoraires . 9 In Memoriam . 9 Membres votants . 10 Album photos . 12 Espace Kendergi . 14 Quarante ans “et plus” d’histoire du CMC Québec . 15 La musicothèque . 16 L’atelier de reprographie . 18 Promotion de la musique de nos compositeurs . 19 Le CMC Québec et le milieu de l’éducation . 20 Sources de financement . 22 Structure organisationnelle . 23 Illustration de la couverture — Christiane Beauregard Infographie — CMC Québec — Louis-Noël Fontaine Imprimé et relié à l’atelier de reprographie du CMC Québec © 2013 — CMC Québec 4 Conseil D’aDministration Conseil exéCutif aDministrateurs Comités Nicolas Gilbert, président Louis Babin COMITÉ DE L’ÉDUCATION Compositeur et écrivain Compositeur Arrangeur et orchestrateur Nicolas Gilbert Barbara Scales, vice-présidente Hélène Laliberté Agente d’artistes Rym Djebbour Louis Babin Latitude45 Arts Directrice en finances personnelles Claire Rousseau Banque Scotia Ana Sokolovic France Lafleur, secrétaire Roxanne Turcotte Vice-présidente et directrice Lori Freedman Tim Brady Québec-Atlantique Compositrice Michel Frigon SOCAN Clarinettiste COMITÉ -

MICHAEL Finnissy {*1946} Vocal Works 1974-2015 »Fantasies

MICHAEL FINNISSy {*1946} vocal works 1974-2015 »Fantasies ... about music, about love and death, about the voice« EXAUDI Vocal Ensemble James Weeks conductor Gesualdo: Libro Sesto {2012-13} ment {Se la mia morte brami} depicts a suave Juliet Fraser, Amy Moore trio of madrigalists ‘in the chamber’ being con - soprano Lucy Goddard tinually soured and overlaid by rawer and more mezzo soprano Tom Williams urgent cries ‘from the street’. No. IV {Quel “no” countertenor Stephen Jeffes, Jonathan Bungard crudel} is a classic female mad scene or revenge tenor aria {albeit for two sopranos, for added force}, Finnissy wrote this set of madrigals in response and no. VI {Resta di darmi noia} moves from to a commission for EXAUDI Vocal Ensemble’s declamatory madrigal to ardent verismo duet tenth birthday concert in 2012; originally a sin - between florid soprano and tenor soloists. Other gle, short pièce d’occasion {now the first piece movements offer surprising vocal combina - in the cycle}, Gesualdo: tions: No. II {Volan Libro Sesto grew into a quasi farfalle} offers major, seven-movement the bizarre juxtaposi - work as Finnissy’s pre - tion of two soprano occupation with the and two bass voices, madrigal genre, and the latter narrating the with the Gesualdo text while the former source material, in - flit around overhead creased. His pro - like the Cupids/moths gramme note for the of the poem – or per - cycle is succinct: ‘Gesu - haps the flame itself. aldo's sixth Book of Its counterpart, No. III Madrigals provides a {Beltà, poi che t’assenti} source for this piece, uses the other four the texts and a few singers – two altos fragments of his music. -

2014Generation

GENERATION 20 ANS YEARS 1994-2014 53 compositeurs 55 concerts 8 tournées canadiennes 75 ateliers de composition 1994-2014 117 lectures d’œuvres YEARS Bravo à l’ECM+ pour son projet Génération ANS fièrement soutenu par la Fondation SOCAN. 20 ON TI A ER ENERATION N E 53 composers G ANS YEARS 55 concerts ❘ 8 Canadian tours 1994 - 20 2014 75 composition workshops 117 new work readings Congratulations to ECM+ for its Generation project proudly supported by the SOCAN Foundation. ISBN 978-2-9814904-0-7G29.95 $ Ensemble contemporain de Montréal (ECM+) Directrice artistique/ Artistic Director : Véronique Lacroix Directrice générale/ General Director : Natalie Watanabe Coordonnatrice/ Coordinator : Anne-Laure Colombani Adjointe à la direction/ Assistant Director : Maude Gareau Adjoint aux communications/ Communications Assistant : Symon Henry ENERATION Graphisme et mise en page/ Graphic design and layout : Louise Durocher Traduction/ Translation : Geneviève Cloutier, Marc Hyland, Keren Penney Révision/ Revision : Martine Chiasson, Keren Penney ANS ❘ YEARS 1994 - 20 2014 ISBN 978-2-9814904-0-7 Dépôt légal, quatrième trimestre 2014 Imprimé au Canada ECM+ © 2014 3890, rue Clark Montréal (Québec) H2W 1W6 Tél. : (514) 524-0173 Fax : (514) 524-0179 www.ecm.qc.ca G Ensemble contemporain de Montréal (ECM+) Directrice artistique/ Artistic Director : Véronique Lacroix Directrice générale/ General Director : Natalie Watanabe Coordonnatrice/ Coordinator : Anne-Laure Colombani Adjointe à la direction/ Assistant Director : Maude Gareau Adjoint aux communications/ Communications Assistant : Symon Henry ENERATION Graphisme et mise en page/ Graphic design and layout : Louise Durocher Traduction/ Translation : Geneviève Cloutier, Marc Hyland, Keren Penney Révision/ Revision : Martine Chiasson, Keren Penney ANS ❘ YEARS 1994 - 20 2014 ISBN 978-2-9814904-0-7 Dépôt légal, quatrième trimestre 2014 Imprimé au Canada ECM+ © 2014 3890, rue Clark Montréal (Québec) H2W 1W6 Tél. -

EXAUDI Lonesingness

lonesingness Exaudi Lucy Goddard and David de Winter (voice) James Weeks (piano) Friday 23rd October 2020 4-5pm Programme John Cage Ear for EAR Lucy, David James Weeks even here i James Zesses Seglias lonesingness David Barbara Monk Feldman The Gentlest Chord Lucy James Weeks even here iiJames Lisa Robertson Almost Lucy, David Michael Pisaro A Bird in the Beast Lucy, David, James James Weeks even here iii James Linda Catlin Smith In Black ink Lucy, James Rodney Lister Devotion Lucy, David, James Programme notes The pieces are performed consecutively without breaks. Lonesingness What is a voice, if not the means to draw us towards each other; to reach across the distance between us and create connection; to enfold us (as the writer Brandon La Belle says) ‘in its sonorities, its rhythms and silences, and intonations’, and bring us closer together? In this time of distances – social, physical, emotional – our programme ‘Lonesingness’ seeks to measure and map those distances, and tentatively to bridge them. John Cage’s austere, antiphonal Ear for EAR (1983) seems to represent a calling-out across some vast space. Solo works by Greek composer Zesses Seglias and Canadian Barbara Monk Feldman articulate in different ways a condition of solitude, as do the short interleaved piano pieces by James Weeks, drawing on material from his recent extended work for violin and piano still here. Lisa Robertson’s brand new work Almost, written for this programme, brings the voices together in pondering the theme of closeness and distance: "This is almost too much. This is almost all over. -

Table of Contents

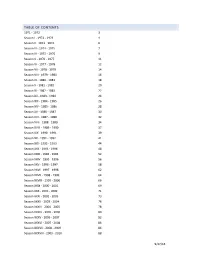

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1971 - 1972 3 Season I - 1972 - 1973 4 Season II - 1973 - 1974 6 Season III - 1974 - 1975 7 Season IV - 1975 - 1976 9 Season V - 1976 - 1977 11 Season VI - 1977 - 1978 12 Season VII - 1978 - 1979 14 Season VIII - 1979 - 1980 16 Season IX - 1980 - 1981 18 Season X - 1981 - 1982 20 Season XI - 1982 - 1983 22 Season XII - 1983 - 1984 24 Season XIII - 1984 - 1985 26 Season XIV - 1985 - 1986 28 Season XV - 1986 - 1987 30 Season XVI - 1987 - 1988 32 Season XVII - 1988 - 1989 34 Season XVIII - 1989 - 1990 37 Season IXX - 1990 - 1991 39 Season XX - 1991 - 1992 41 Season XXI - 1992 - 1993 44 Season XXII - 1993 - 1994 48 Season XXIII - 1994 - 1995 52 Season XXIV - 1995 - 1996 56 Season XXV - 1996 - 1997 58 Season XXVI - 1997 - 1998 62 Season XXVII - 1998 - 1999 64 Season XXVIII - 1999 - 2000 66 Season XXIX - 2000 - 2001 69 Season XXX - 2001 - 2002 71 Season XXXI - 2002 - 2003 73 Season XXXII - 2003 - 2004 76 Season XXXIII - 2004 - 2005 78 Season XXXIV - 2005 - 2006 80 Season XXXV - 2006 - 2007 82 Season XXXVI - 2007 - 2008 84 Season XXXVII - 2008 - 2009 86 Season XXXVIII - 2009 - 2010 88 9/27/16 SEASON XXXIX - 2010 - 2011 91 SEASON XL - 2011 - 2012 95 SEASON XLI - 2012 - 2013 98 SEASON XLII - 2013 - 2014 102 SEASON XLIII - 2014 - 2015 107 SEASON XLIV - 2015 - 2016 111 SEASON XLV - 2016 - 2017 115 Abbreviations of Musical Instruments 118 9/27/16 1971 - 1972 ARRAY IN HISTORY October 1971 Informal meetings held to discuss experimental composition and performance technique. Alex Pauk, John Fodi, Clifford Ford, Marjan Mozetich, Gary -

Table of Contents

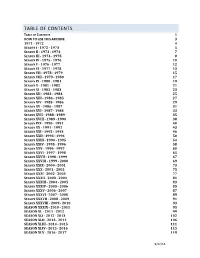

TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 HOW TO USE THIS ARCHIVE 3 1971 - 1972 4 SEASON I - 1972 - 1973 5 SEASON II - 1973 - 1974 7 SEASON III - 1974 - 1975 8 SEASON IV - 1975 - 1976 10 SEASON V - 1976 - 1977 12 SEASON VI - 1977 - 1978 13 SEASON VII - 1978 - 1979 15 SEASON VIII - 1979 - 1980 17 SEASON IX - 1980 - 1981 19 SEASON X - 1981 - 1982 21 SEASON XI - 1982 - 1983 23 SEASON XII - 1983 - 1984 25 SEASON XIII - 1984 - 1985 27 SEASON XIV - 1985 - 1986 29 SEASON XV - 1986 - 1987 31 SEASON XVI - 1987 - 1988 33 SEASON XVII - 1988 - 1989 35 SEASON XVIII - 1989 - 1990 38 SEASON IXX - 1990 - 1991 40 SEASON XX - 1991 - 1992 43 SEASON XXI - 1992 - 1993 46 SEASON XXII - 1993 - 1994 50 SEASON XXIII - 1994 - 1995 54 SEASON XXIV - 1995 - 1996 58 SEASON XXV - 1996 - 1997 60 SEASON XXVI - 1997 - 1998 65 SEASON XXVII - 1998 - 1999 67 SEASON XXVIII - 1999 - 2000 69 SEASON XXIX - 2000 - 2001 73 SEASON XXX - 2001 - 2002 75 SEASON XXXI - 2002 - 2003 77 SEASON XXXII - 2003 - 2004 81 SEASON XXXIII - 2004 - 2005 83 SEASON XXXIV - 2005 - 2006 85 SEASON XXXV - 2006 - 2007 87 SEASON XXXVI - 2007 - 2008 89 SEASON XXXVII - 2008 - 2009 91 SEASON XXXVIII - 2009 - 2010 93 SEASON XXXIX - 2010 - 2011 95 SEASON XL - 2011 - 2012 99 SEASON XLI - 2012 - 2013 102 SEASON XLII - 2013 - 2014 106 SEASON XLIII - 2014 - 2015 111 SEASON XLIV - 2015 - 2016 115 SEASON XLV - 2016 - 2017 119 9/27/16 SEASON XLVI – 2017 – 2018 122 SEASON XLVII – 2018 – 2019 126 LEGEND 130 ABBREVIATIONS OF MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS 131 9/27/16 HOW TO USE THIS ARCHIVE A legend can be found at the end of the document showing how musical compositions and events are described and their formatting. -

In a Uvic Minute: Concert of Miniatures Music by Uvic School of Music Alumni Selected from a Call for Scores

Orion Series in Fine Arts presents In a UVic Minute: Concert of Miniatures Music by UVic School of Music alumni selected from a call for scores. Saturday, February 3 • 2:30 p.m. Phillip T. Young Recital Hall | Free admission Heather Roche, clarinet (Orion guest artist) Tzenka Dianova, piano Chroma Quartet: Ilya Gotchev, violin Carlos Quijano, violin Felix Alanis, violin/viola Manuel Cruz, violoncello Please hold your applause until the end of the program. Centimetres Natalie Dzbik FLIQRA Ross Curran The Honey Badger Ivana Jokic Flourish 1 Nicholas Fairbank Of things returned Kristy Farkas Susurro Marci Rabe momentary encounters (6) Alex Jang Fulcra Dave Riedstra Lamento Linda Catlin Smith refortified // retrofitted: two instances for clarinet Nolan Krell Two for Piano Trio Chedo Barone Tributary Anna Höstman Sinnlose Maschinen David Foley Victoria Miniature Ryan Noakes festina lente Rodney Sharman Cecilia’s Epilogue Matthew Kaufhold Trio for two violins and B-flat clarinet Brian Kardash xk-y.o. 616 Alexander Simon Breakwater Janet Sit Praeludium e Fantasia sul B.A.C.H Christopher Butterfield We are grateful to the UVic Alumni Association for their generous funding. IN A UVIC MINUTE BIOGRAPHIES Heather Roche, clarinet Born in Canada, clarinetist Heather Roche (BMus ’05) lives in London. Recently referred to as “The Queen of Multiphonics” on BBC Radio 3, she appears regularly as a soloist and chamber musician at European festivals, including the London Contemporary Music Festival, Acht Brücken (Cologne), Svensk Musikfår (Stockholm), WittenerTage für neue Kammermusik (Germany), Musica Nova (Helsinki), MusikFest (Berlin), BachFest (Leipzig), Angora (Paris), etc. She was a founding member of an ensemble for contemporary chamber music in Cologne, hand werk, and has also played with the Musikfabrik (Cologne), the WDR Symphony Orchestra (Cologne), mimitabu (Gothenburg), Alisios Camerata (Zagreb), Apartment House (London) and ensemble Proton (Bern), among others.