Putting Fishermen's Knowledge to Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines for Electrofishing Waters Containing Salmonids Listed Under

National Guidelines for Electrofishing Waters Marine Fisheries Containing Salmonids Listed Under Service the Endangered Species Act June 2000 Purpose and Scope The purpose of this document is to provide guidelines for the safe use of backpack electrofishing in waters containing salmonids listed by the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). It is expected that these guidelines will help improve electrofishing technique in ways which will reduce fish injury and increase electrofishing efficiency. These guidelines and sampling protocol were developed from NMFS research experience and input from specialists in the electrofishing industry and fishery researchers. This document outlines electrofishing procedures and guidelines that NMFS has determined to be necessary and advisable when working in freshwater systems where threatened or endangered salmon and steelhead may be found. As such, the guidelines provide a basis for reviewing proposed electrofishing activities submitted to NMFS in the context of ESA Section 10 permit applications as well as scientific research activities proposed for coverage under an ESA Section 4(d) rule. These guidelines specifically address the use of backpack electrofishers for sampling juvenile or adult salmon and steelhead that are not in spawning condition. Electrofishing in the vicinity of adult salmonids in spawning condition and electrofishing near redds are not discussed as there is no justifiable basis for permitting these activities except in very limited situations (e.g., collecting brood stock, fish rescue, etc.). The guidelines also address sampling and fish handling protocols typically employed in electrofishing studies. While the guidelines contain many specifics, they are not intended to serve as an electrofishing manual and do not eliminate the need for good judgement in the field. -

Small-Scale Fisheries of San Miguel Bay, Philippines: Occupational and Geographic Mobility

Small-scale fisheries of San Miguel Bay, Philippines: occupational and geographic mobility Conner Bailey 1982 INSTITUTE OF FISHERIES DEVELOPMENT AND RESEARCH COLLEGE OF FISHERIES, UNIVERSITY OF THE PHILIPPINES IN THE VISAYAS QUEZON CITY, PHILIPPINES INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR LIVING AQUATIC RESOURCES MANAGEMENT MANILA, PHILIPPINES THE UNITED NATIONS UNIVERSITY TOKYO, JAPAN Small-scale fisheries of San Miguel Bay, Philippines: occupational and geographic mobility CONNER BAILEY 1982 Published jointly by the Institute of Fisheries Development and Research, College of Fisheries, University of the Philippines in the Visayas, Quezon City, Philippines; the International Center for Living Aquatic Resources Management, Manila, Philippines; and the United Nations University,Tokyo, Japan. Printed in Manila, Philippines Bailey, C. 1982. Small-scale fisheries of San Miguel Bay, Philippines: occupational and geographic mobility. ICLARM Technical Reports 10, 57 p. Institute of Fisheries Development and Research, College of Fisheries, University of the Philippines in the Visayas, Quezon City, Philippines; International Center for Living Aquatic Resources Management, Manila, Philippines; and the United Nations University, Tokyo, Japan. Cover: Upper: Fishermen and buyers on the beach, San Miguel Bay. Lower: Satellite view of the Bay, to the right of center. [Photo, NASA, U.S.A.]. ISSN 0115-5547 ICLARM Contribution No. 137 Table of Contents List of Tables......................................................................... ................... ..................................... -

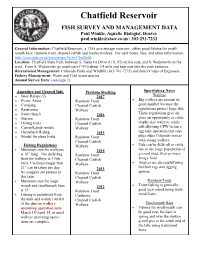

Chatfield Reservoir

Chatfield Reservoir FISH SURVEY AND MANAGEMENT DATA Paul Winkle, Aquatic Biologist, Denver [email protected] / 303-291-7232 General Information: Chatfield Reservoir, a 1355 acre storage reservoir, offers good fishing for small- mouth bass, rainbow trout, channel catfish and trophy walleye. For park hours, fees, and other information: http://cpw.state.co.us/placestogo/Parks/Chatfield Location: Chatfield State Park, between S. Santa Fe Drive (U.S. 85) on the east, and S. Wadsworth on the west. From S. Wadsworth go south past C-470 about 1/4 mile and turn east into the park entrance. Recreational Management: Colorado Parks and Wildlife (303-791-7275) and Army Corps of Engineers. Fishery Management: Warm and Cold water species Annual Survey Data: (see page 2) Amenities and General Info. Previous Stocking Sportfishing Notes Boat Ramps (2) 2017 Walleye Picnic Areas Rainbow Trout Big walleye are present in Camping Channel Catfish good number because the Restrooms Walleye regulations protect large fish. Swim Beach 2016 These regulations give an- Marina Rainbow Trout glers an opportunity to catch Hiking trails Channel Catfish trophy size walleye, while Canoe/Kayak rentals Walleye still allowing CPW to run a Horseback Riding 2015 egg take operation that sup- Model Airplane Field Rainbow Trout plies other Colorado waters Channel Catfish with young walleye. Fishing Regulations Walleye Fish can be difficult to catch Minimum size for walleyes 2014 due to the large population of is 18” long. The daily bag Rainbow Trout gizzard shad, their primary limit for walleye is 3 fish. Channel Catfish forage food. Only 1 walleye longer than Walleye Anglers are successful using 21” can be taken per day. -

Proceedings of the International Cyanide Detection Testing Workshop

Proceedings of the International Cyanide Detection Testing Workshop February 6-8, 2008 Orlando, Florida Edited by Andrew W. Bruckner Glynnis G. Roberts U.S. Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-OPR-40 August 2008 This publication should be cited as: Bruckner, A.W. and G. Roberts (editors). 2008. Proceedings of the International Cyanide Detection Testing Workshop. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-OPR-40, Silver Spring, MD 164 pp. Signifi cant support for the development of this document was provided by NOAA Fisheries, Offi ce of Habitat Conservation, and NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program. The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and the participants of the workshop, and do not necessarily refl ect the offi cial views or policies of the U.S. Government, NOAA or DOS. Front Cover Images: (Top) James Cervino – A fi sher uses cyanide to catch marine ornamental fi sh; (Bottom) Stephen Why – Pens used in Micronesia to hold live reef food fi sh. Additional copies of this publication may be requested from: John Foulks National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service Offi ce of Habitat Conservation 1315 East West Highway Silver Spring, MD 20910 [email protected] Proceedings of the Cyanide Detection Testing Workshop Edited by Andrew W. Bruckner and Glynnis G. Roberts Offi ce of Habitat Conservation Ecosystem Assessment Division NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service 1315 East-West Highway Silver Spring, MD 20910-3282 NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-OPR-40 August 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos Gutierrez, Secretary National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Vice Admiral Conrad C. -

August 2017 - Issue #78

August 2017 - Issue #78 1 Crappie NOW August 2017 August 2017 Features Sizzling Hot Crappie.....4 by John E. Phillips Crappie fishing can be tough in the summer but here’s how to find some action. ICAST Showcases New Products & Winners....10 by Tim Huffman Wholesalers and media get first look at the new fishing and accessory items for 2018. See what got voted as the hot fishing items for next year. Alabama Bucket List....16 by Ron Presley If you enjoy fishing a variety of techniques, the Alabama River might be your cup of tea. Spider rigging, single poling, and longlining all work well on the river to put slab crappie in the boat. What’s Up Dock?.....22 By John N. Felsher, photos by Ron Presley Docks offer good fishing much of the year. Knowing some of the basic rules helps put more fish on the end of your line. Departments Vern’s Cooking & Tidbits....28 Crappie Calendar....32 Tournament Results....30 Crappie Clubs....33 2 Crappie NOW August 2017 Opening Cast I just returned from a very successful and EDITOR/ SR. WRITER informative ASA ICAST Show in Orlando Florida where fishing companies presented IN MEMORIAM their new products for 2018 to the media and industry representatives/buyers. It WRITERS was bigger than any before it Darl Black and my feet took a pounding Vic Attardo for three days trying to meet Ron Presley with the companies attending. Vernon Summerlin I was pleasantly surprised to see a substantial John Phillips increase in the number of companies that were Josh Gowan producing or about to produce products for all crappie Greg McCain fishermen, women and children. -

Review of Policy, Legal, and Institutional Arrangements for Philippine Compliance with the Wcpf Convention

REVIEW OF POLICY, LEGAL, AND INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR PHILIPPINE COMPLIANCE WITH THE WCPF CONVENTION Jay L. Batongbacal TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. THE WCPF CONVENTION 3 2.1 General Background 3 2.1.1 The Commission 4 2.1.2 The Secretariat and Subsidiary Bodies 5 A. Secretariat 5 B. Other Subsidiary Bodies 6 B.1 Scientific Committee 6 B.2 Technical and Compliance Committee 6 B.3 Northern Committee 7 2.1.3 Decision-making 7 2.1.4 Cooperation with Other Organizations 8 2.1.5 Financial Arrangements 8 2.2 Management Policy in the Convention Area 8 2.2.1 Precautionary Approach 8 2.2.2 Ecosystem-based Approach 9 2.2.3 Compatibility of Measures 10 2.2.4 Due Regard for Disadvantaged and Good Faith 11 2.2.5 Management Actions 11 2.3 Member's Obligations 12 2.3.1 General Obligations 12 2.3.2 Compliance and Enforcement Obligations 13 A. Flag State Obligations 13 B. Boarding and Inspection 14 C. Investigation 15 D. Punitive Measures 17 E. Port State Measures 17 2.4 Conservation and Management Measures 18 2.4.1 Fishing Vessel Registry Standards 18 A. Vessel Marking and Identification 18 B. Authorization to Fish 19 C. Record of Authorized Fishing Vessels 20 D. Commission Vessel Monitoring System 21 E. IUU Vessel 'Blacklisting' 21 F. Charter Notification Scheme 22 G. Vessel Without Nationality 22 2.4.2 Fishing Operation Regulations 23 A. Transhipment 23 B. Gear Restrictions 24 C. Catch Retention 25 D. Area/Season Closures 25 E. Mitigation Measures 26 2.4.3 Species-specific Restrictions 27 2.5 Other 'Soft' Obligations 28 2.6 Peaceful Settlement of Disputes 29 3. -

Socio-Economics of Trawl Fisheries in Southeast Asia and Papua New Guinea

Socio-economics of trawl fisheries in Sout ISSN 2070-6103 50 FAO FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE PROCEEDINGS FAO FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE PROCEEDINGS 50 50 Socio-economics of trawl fisheries in Southeast Asia and Papua New Guinea Proceedings of the Regional Workshop on Trawl Fisheries Socio-economics 26-27 October 2015 Da Nang, Vietnam Socio-economics of trawl and Socio-economic Write-shop 25-26 April 2016 fisheries in Southeast Asia and Cha Am, Thailand Socio-economic surveys were carried out in pilot sites in Papua New Guinea (Gulf of Papua Prawn Fishery), Philippines (Samar Sea), Papua New Guinea Thailand (Trat and Chumphon) and Viet Nam (Kien Giang) under the project, Strategies for trawl fisheries bycatch management (REBYC-II CTI), funded by the Global Environment Facility and executed by FAO. In Indonesia, no study was conducted owing to the ban on trawl Proceedings of the Regional Workshop on Trawl Fisheries Socio-economics fisheries beginning January 2015. However, a paper based on key 26-27 October 2015 informant interviews was prepared. The socio-economic studies were Da Nang, Viet Nam undertaken to understand the contribution of trawl fisheries to food and security and livelihoods and determine the potential impacts of Socio-economic Write-shop management measures on stakeholder groups. Among the 25-26 April 2016 socio-economic information collected were the following: Cha Am, Thailand demographic structure of owners and crew; fishing practices – boat, gear, season, duration; catch composition, value chain and markets; contribution to livelihoods, food security and nutrition; role of women; heast Asia and Papua New Guinea costs and income from trawling; catch/income sharing arrangements; linkages with other sectors; and perceptions – resources, participation, compliance and the future. -

Guide to the Classification of Fishing Gear in the Philippines

U.S. Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Wildlife Services Historic document – Content may not reflect current scientific research, policies or practices. GUIDE TO THE CLASSIFICATION OF FISHING GEAR IN THE PHILIPPINES By AGUSTIN F. UMALI, Ichthyologist Illustrations by Silas G. Duran RESEARCH REPORT 17 Fish and Wildlife Service, Albert M. Day, Director United States Department of the Interior, Oscar L. Chapman, Secretary UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE : 1950 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, United States Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price 40 cents ABSTRACT One of the serious handicaps in the administration and manage ment of the fisheries of the Philippines has been the lack of standardized nomenclature for fishing gear. This publication attempts to solve the problem. It is divided into five parts: The first presents a basic clas sification of fishing gear; the second is a key by means of which fishing gear can be identified and new terms for fishing gear can be properly classified; the third defines and illustrates various types of fishing gear; the fourth is a tabular classification of local Filipino di alect names; and the fifth is a glossary including definitions of more than a thousand terms. CONTENTS Classification of the Gear. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 2 Part I. Basic Classification of Fishing Gear. • • • • • • • . • • • • • • • • • 6 Part II. Key to the Identification of Classes of Fishing Gear. • . • -

Destructive Fishing Words & Photography by Arjan Rajasuriya, IUCN, Sri Lanka Country Office

Fishing net entangled on corals Destructive Fishing Words & Photography by Arjan Rajasuriya, IUCN, Sri Lanka Country Office 66 LT | AUGUST 2015 LT | AUGUST 2015 67 Effects of dynamite fishing on marine life in coral reefs oral reefs are among the most The southern and eastern coastal areas of Purse seining is a fishing method that Photo by Nishan Perera productive natural ecosystems in Sri Lanka are well-known for blast fishing. encircles an entire group of fish using a large C the marine environment. Coral Fishermen target species such as jacks net. This method can deplete fish stocks reefs harbour a large number of species (Family: Carangidae), and fusiliers (Family: rapidly if it is done by many fishermen and and it has been estimated at about 25% Caesionidae) that aggregate seasonally at regularly. Such a destructive large scale of all marine species are found on coral prominent locations on the reefs to spawn. fishing operation is taking place in the reefs. A coral reef functions as a buffer These species aggregate where currents northwestern coastal waters from Kalpitiya to against coast erosion and is a breeding and converge or where the reef structure is high Mannar. The net used to carry out the purse nursery ground of many species including and where other underwater habitats such seining is locally known as ‘Laila net’. There economically important reef fish and other as shipwrecks are present. Blast fishing has are different forms of modified ‘Laila nets’ species such as spiny lobsters, seacucumber increased recently with the technological and is used in combination with explosives. -

Assessing the Importance of Fishing Impacts on Hawaiian Coral Reef Fish

Environmental Conservation 35 (3): 261–272 © 2008 Foundation for Environmental Conservation doi:10.1017/S0376892908004876 Assessing the importance of fishing impacts on Hawaiian coral reef fish assemblages along regional-scale human population gradients I. D. WILLIAMS1,2∗,W.J.WALSH2 ,R.E.SCHROEDER3 ,A.M.FRIEDLANDER4 , B. L. RICHARDS3 AND K. A. STAMOULIS2 1Hawaii Cooperative Fishery Research Unit, Department of Zoology, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822, USA, 2Hawaii Division of Aquatic Resources, Honokohau Marina, 74-380B Kealakehe Parkway, Kailua-Kona, Hawaii 96740, USA, 3Joint Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research (JIMAR), University of Hawaii and Coral Reef Ecosystems Division (CRED) NOAA, National Marine Fisheries Service, Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, 1125B Ala Moana Boulevard, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA and 4NOAA/NOS/NCCOS/ CCMA- Biogeography Branch and The Oceanic Institute, Makapuu Point/41-202 Kalanianaole Highway,Waimanalo, Hawaii 96795, USA Date submitted: 29 January 2008; Date accepted: 26 May 2008; First published online: 29 August 2008 SUMMARY generally, coral reef areas within marine reserves tend to have two or more, sometimes up to 10 times, the biomass Humans can impact coral reef fishes directly by fishing, of targeted fishes when compared to nearby fished areas or or indirectly through anthropogenic degradation of pre-closure stocks (Russ & Alcala 1989, 2003; Polunin & habitat. Uncertainty about the relative importance Roberts 1993; Friedlander et al. 2007b; McClanahan et al. of those can -

Modelling the Effects of Destructive Fishing Practices on Tropical Coral Reefs

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published March 31 Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. l Modelling the effects of destructive fishing practices on tropical coral reefs S. B. Sailal, V. Lj. ~ocic~,J. W. McManusl ' International Center for Marine Resource Development, Mathematics Department The University of Rhode Island, Kingston, Rhode Island 02881, USA ABSTRACT: A literature review of the use of underwater explosives indicated that the largest lethal zone for swimbladder fishes is located near the surface of the water. Mortality in this zone is due to rupture of the swimbladder from negative pressure induced by cavitation of the near-surface water volume from a subsurface explosion. Observational studies of blast fishing in the Philippines indicated that valuable pelagic species rather than typical coral reef species were the primary targets. Empirical data on the extent of various destructive fishing practices (blast fishing, anchor damage, and use of poisons), as well as coral regrowth estimates, provided inputs to a nomographic model of the reef ecosystem. The model provided time graphs of fish diversity and the amount of coral regrowth under various conditions. The results of the simulation model studies indicated that the sum of all current destructive practices was sufficient to continue loss of diversity and loss of live coral cover for about 25 yr before any recovery was expected. On the other hand a reduction in the rate of destructive fishing to about 30 % of the current level would permit continuing slow recovery of both diversity and live coral cover. Available observational information suggests that this might best be accomplished by attempting to eliminate the use of poisons (such as cyanide) in reef areas and reducing anchor damage in addition to reducing blast fishing in coral areas. -

FISHING NEWSLETTER 2020/2021 Table of Contents FWP Administrative Regions and Hatchery Locations

FISHING NEWSLETTER 2020/2021 Table of Contents FWP Administrative Regions and Hatchery Locations .........................................................................................3 Region 1 Reports: Northwest Montana ..........................................................................................................5 Region 2 Reports: West Central Montana .....................................................................................................17 Region 3 Reports: Southwest Montana ........................................................................................................34 Region 4 Reports: North Central Montana ...................................................................................................44 Region 5 Reports: South Central Montana ...................................................................................................65 Region 6 Reports: Northeast Montana ........................................................................................................73 Region 7 Reports: Southeast Montana .........................................................................................................86 Montana Fish Hatchery Reports: .......................................................................................................................92 Murray Springs Trout Hatchery ...................................................................................................................92 Washoe Park Trout Hatchery .......................................................................................................................93