Regional Fisheries Livelihood Program (RFLP) (GCP/RAS/237/SPA)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

As of 09 July 2012 Rural Bank Partner Address

RURAL BANK PARTNER ADDRESS AS OF 09 JULY 2012 Pick-up channel Branch Address 1 Bangko Kabayan BALAYAN BRANCH Antorcha St., Balayan, Batangas 2 Bangko Kabayan AGONCILLO BRANCH J. Mendoza Street, Poblacion, Agoncillo, Batangas 3 Bangko Kabayan BATANGAS CITY BRANCH Romero Dy. Bldg., P. Burgos St. Batangas City 4 Bangko Kabayan CALACA BRANCH Marasigan St. Poblacion, Calaca, Batangas 5 Bangko Kabayan CALATAGAN BRANCH Ayala St. Brgy 3, Poblacion Calatagan, Batangas 6 Bangko Kabayan CUENCA BRANCH National Road, Poblacion, Cuenca, Batangas 7 Bangko Kabayan IBAAN BRANCH Santiago Street, Poblacion, Ibaan, Batangas 8 Bangko Kabayan LEMERY BRANCH Ilustre St., Poblacion, Lemery, Batangas 9 Bangko Kabayan MABINI BRANCH Poblacion Mabini, Batangas 10 Bangko Kabayan NASUGBU BRANCH P. Rinosa St. Poblacion Nasugbu, Batangas 11 Bangko Kabayan ROSARIO BRANCH Barangay C Poblacion Rosario, Batangas 12 Bangko Kabayan SAN JOSE BRANCH Taysan, San Jose, Batangas 13 Bangko Kabayan SAN JUAN BRANCH Gen. Luna Street, Poblacion San Juan, Batangas 14 Bangko Kabayan SAN PASCUAL BRANCH San Antonio, San Pascual, Batangas 15 Bangko Kabayan TANAUAN BRANCH J.P. Laurel Highway (National Highway), Tanauan City, Batangas 16 Bangko Kabayan LIPA CITY BRANCH Laguerta Bldg., P. Torres ST., Lipa City 17 Bank of Florida PULILAN BRANCH Barangay Cutcut, Pulilan, Bulacan 18 Bank of Florida GLOBAL CITY BRANCH Unit 6, 3rd Flr., The Fort Strip Building, Bonifacio Center, Fort Bonifacio, Global City, Taguig 19 Bank of Florida ARAYAT BRANCH Poblacion, Arayat, Pampanga 20 Bank of Florida CANDABA BRANCH Poblacion, Candaba, Pampanga 21 Bank of Florida FLORIDABLANCA BRANCH Poblacion, Floridablanca, Pampanga 22 Bank of Florida GUAGUA BRANCH Plaza Burgos, Guagua, Pampanga 23 Bank of Florida MABALACAT BRANCH Sta. -

Guidelines for Electrofishing Waters Containing Salmonids Listed Under

National Guidelines for Electrofishing Waters Marine Fisheries Containing Salmonids Listed Under Service the Endangered Species Act June 2000 Purpose and Scope The purpose of this document is to provide guidelines for the safe use of backpack electrofishing in waters containing salmonids listed by the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). It is expected that these guidelines will help improve electrofishing technique in ways which will reduce fish injury and increase electrofishing efficiency. These guidelines and sampling protocol were developed from NMFS research experience and input from specialists in the electrofishing industry and fishery researchers. This document outlines electrofishing procedures and guidelines that NMFS has determined to be necessary and advisable when working in freshwater systems where threatened or endangered salmon and steelhead may be found. As such, the guidelines provide a basis for reviewing proposed electrofishing activities submitted to NMFS in the context of ESA Section 10 permit applications as well as scientific research activities proposed for coverage under an ESA Section 4(d) rule. These guidelines specifically address the use of backpack electrofishers for sampling juvenile or adult salmon and steelhead that are not in spawning condition. Electrofishing in the vicinity of adult salmonids in spawning condition and electrofishing near redds are not discussed as there is no justifiable basis for permitting these activities except in very limited situations (e.g., collecting brood stock, fish rescue, etc.). The guidelines also address sampling and fish handling protocols typically employed in electrofishing studies. While the guidelines contain many specifics, they are not intended to serve as an electrofishing manual and do not eliminate the need for good judgement in the field. -

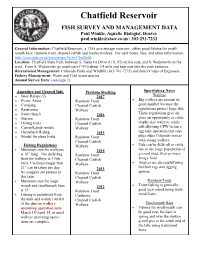

Chatfield Reservoir

Chatfield Reservoir FISH SURVEY AND MANAGEMENT DATA Paul Winkle, Aquatic Biologist, Denver [email protected] / 303-291-7232 General Information: Chatfield Reservoir, a 1355 acre storage reservoir, offers good fishing for small- mouth bass, rainbow trout, channel catfish and trophy walleye. For park hours, fees, and other information: http://cpw.state.co.us/placestogo/Parks/Chatfield Location: Chatfield State Park, between S. Santa Fe Drive (U.S. 85) on the east, and S. Wadsworth on the west. From S. Wadsworth go south past C-470 about 1/4 mile and turn east into the park entrance. Recreational Management: Colorado Parks and Wildlife (303-791-7275) and Army Corps of Engineers. Fishery Management: Warm and Cold water species Annual Survey Data: (see page 2) Amenities and General Info. Previous Stocking Sportfishing Notes Boat Ramps (2) 2017 Walleye Picnic Areas Rainbow Trout Big walleye are present in Camping Channel Catfish good number because the Restrooms Walleye regulations protect large fish. Swim Beach 2016 These regulations give an- Marina Rainbow Trout glers an opportunity to catch Hiking trails Channel Catfish trophy size walleye, while Canoe/Kayak rentals Walleye still allowing CPW to run a Horseback Riding 2015 egg take operation that sup- Model Airplane Field Rainbow Trout plies other Colorado waters Channel Catfish with young walleye. Fishing Regulations Walleye Fish can be difficult to catch Minimum size for walleyes 2014 due to the large population of is 18” long. The daily bag Rainbow Trout gizzard shad, their primary limit for walleye is 3 fish. Channel Catfish forage food. Only 1 walleye longer than Walleye Anglers are successful using 21” can be taken per day. -

Review of Policy, Legal, and Institutional Arrangements for Philippine Compliance with the Wcpf Convention

REVIEW OF POLICY, LEGAL, AND INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR PHILIPPINE COMPLIANCE WITH THE WCPF CONVENTION Jay L. Batongbacal TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. THE WCPF CONVENTION 3 2.1 General Background 3 2.1.1 The Commission 4 2.1.2 The Secretariat and Subsidiary Bodies 5 A. Secretariat 5 B. Other Subsidiary Bodies 6 B.1 Scientific Committee 6 B.2 Technical and Compliance Committee 6 B.3 Northern Committee 7 2.1.3 Decision-making 7 2.1.4 Cooperation with Other Organizations 8 2.1.5 Financial Arrangements 8 2.2 Management Policy in the Convention Area 8 2.2.1 Precautionary Approach 8 2.2.2 Ecosystem-based Approach 9 2.2.3 Compatibility of Measures 10 2.2.4 Due Regard for Disadvantaged and Good Faith 11 2.2.5 Management Actions 11 2.3 Member's Obligations 12 2.3.1 General Obligations 12 2.3.2 Compliance and Enforcement Obligations 13 A. Flag State Obligations 13 B. Boarding and Inspection 14 C. Investigation 15 D. Punitive Measures 17 E. Port State Measures 17 2.4 Conservation and Management Measures 18 2.4.1 Fishing Vessel Registry Standards 18 A. Vessel Marking and Identification 18 B. Authorization to Fish 19 C. Record of Authorized Fishing Vessels 20 D. Commission Vessel Monitoring System 21 E. IUU Vessel 'Blacklisting' 21 F. Charter Notification Scheme 22 G. Vessel Without Nationality 22 2.4.2 Fishing Operation Regulations 23 A. Transhipment 23 B. Gear Restrictions 24 C. Catch Retention 25 D. Area/Season Closures 25 E. Mitigation Measures 26 2.4.3 Species-specific Restrictions 27 2.5 Other 'Soft' Obligations 28 2.6 Peaceful Settlement of Disputes 29 3. -

FISHING NEWSLETTER 2020/2021 Table of Contents FWP Administrative Regions and Hatchery Locations

FISHING NEWSLETTER 2020/2021 Table of Contents FWP Administrative Regions and Hatchery Locations .........................................................................................3 Region 1 Reports: Northwest Montana ..........................................................................................................5 Region 2 Reports: West Central Montana .....................................................................................................17 Region 3 Reports: Southwest Montana ........................................................................................................34 Region 4 Reports: North Central Montana ...................................................................................................44 Region 5 Reports: South Central Montana ...................................................................................................65 Region 6 Reports: Northeast Montana ........................................................................................................73 Region 7 Reports: Southeast Montana .........................................................................................................86 Montana Fish Hatchery Reports: .......................................................................................................................92 Murray Springs Trout Hatchery ...................................................................................................................92 Washoe Park Trout Hatchery .......................................................................................................................93 -

Impacts of Fishing Line and Other Litter by Deborah Weisberg

Impacts of Fishing Line and Other Litter by Deborah Weisberg During cleanup of the North Branch of the Susquehanna River, a canoe barge was crafted and used to transport photo-Melissa Rohm heavy debris out of a shallow water inlet. Dave Miko has seen a lot of strange sights as Division of It has spurred some conservationists to try to avert more Fisheries Management chief for the Pennsylvania Fish & losses. According to trout guide George Daniel of TCO Fly Boat Commission (PFBC). Shop in State College, Trout Unlimited chapters in central But, few compare to the hourglass-shaped trout he has Pennsylvania have stepped up landowner outreach efforts as encountered on streams, where they have grown around fishing pressure mounts on Penn’s Creek, the Little Juniata plastic bottleneck rings that someone tossed into the water. River and other blue-ribbon streams. “I have seen it twice when I was electrofishing, so it On Lake Erie, the Pennsylvania Steelhead Association probably happens even more,” said Miko. “I cut the rings and and other groups make litter pickups and goodwill gestures hoped for the best, but it’s sad and disturbing.” towards landowners a major part of their mission. With More often, angler and boater carelessness takes other PFBC spending millions of dollars to acquire easements on forms, as evidenced by bait cups, plastic water bottles and Elk Creek, Walnut Creek and other popular fisheries, this tangled fishing lines that blight stream banks and lake shores. kind of private-sector support helps lay the groundwork for It takes thousands of years for petroleum-based plastics to future access purchases. -

Fishing for Fairness Poverty, Morality and Marine Resource Regulation in the Philippines

Fishing for Fairness Poverty, Morality and Marine Resource Regulation in the Philippines Asia-Pacific Environment Monograph 7 Fishing for Fairness Poverty, Morality and Marine Resource Regulation in the Philippines Michael Fabinyi Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Fabinyi, Michael. Title: Fishing for fairness [electronic resource] : poverty, morality and marine resource regulation in the Philippines / Michael Fabinyi. ISBN: 9781921862656 (pbk.) 9781921862663 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Fishers--Philippines--Attitudes. Working poor--Philippines--Attitudes. Marine resources--Philippines--Management. Dewey Number: 333.91609599 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Cover image: Fishers plying the waters of the Calamianes Islands, Palawan Province, Philippines, 2009. Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press Contents Foreword . ix Acknowledgements . xiii Selected Tagalog Glossary . xvii Abbreviations . xviii Currency Conversion Rates . xviii 1 . Introduction: Fishing for Fairness . 1 2 . Resource Frontiers: Palawan, the Calamianes Islands and Esperanza . 21 3 . Economic, Class and Status Relations in Esperanza . 53 4 . The ‘Poor Moral Fisher’: Local Conceptions of Environmental Degradation, Fishing and Poverty in Esperanza . 91 5 . Fishing, Dive Tourism and Marine Protected Areas . 121 6 . Fishing in Marine Protected Areas: Resistance, Youth and Masculinity . -

7 JUN 30 PZ 155 of the REPUBLIC of the PHILIPPINES ) FIRST REGULAR SESSION 1 >,E.,I., ' '% SENATE ' ' 4;) ~~~~~Lv~*: Senate Bill No

FOURTEENTH CONGRESS 1 7 JUN 30 PZ 155 OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES ) FIRST REGULAR SESSION 1 >,e.,I., ' '% SENATE ' ' 4;) ~~~~~lV~*: Senate Bill No. 171 , Introduced by Sen. M.A.Madrigal EXPLANATORY NOTE The Tubbataha Reef is located within Central Sulu Sea. It is part of the Sulu West Sea Marine Triangle under the jurisdiction of Cagayancillo, Palawan. It is made up of two atolls, the North Reef and South Reef. The Tubbataha Reef is home to seven (7) species of seagrasses, which are food for the endangered marine turtle, and seventy-one (71) algae, and four hundred seventy-nine species of marine fishes. Eighty-six percent (86%) of the total coral species in the Philippines are found in Tubbataha Reef area. The fish biomass in the Tubbataha Reef is more than average. It is the rookery of twenty-three species of migratory and resident sea birds, some of which is globally threatened. It is a nesting ground for two species of endangered marine turtles. Due to its biodiversity and ecological significance, the Tubbataha Reef Natural Park was declared a protected sanctuary in August 2006 through Presidential Proclamation No. 1126. In line with the State's policy of securing for the Filipino people of present and future generations the perpetual existence of all native plants and animals, it is incumbent upon the Congress to enact a law to provide for the management, protection, sustainable development and rehabilitation of the Tubattaha Reef Natural Park. This shall be established within the framework of the National Integrated Protected Area System (NIPAS) Act, or Republic Act of 7586, while considering the welfare and recognizing the rights of all the communities living therein especially the indigenous peoples. -

This Directory Is As of August 04, 2016 METRO MANILA PICK-UP CHANNEL PROVINCE AREA/CITY ADDRESS PALAWAN PAWNSHOP METRO MANILA MANILA 1738 D JUAN ST

METRO MANILA PICK-UP CHANNEL PROVINCE AREA/CITY ADDRESS PALAWAN PAWNSHOP METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY UNIT B-5 A. MABINI STREET, CALOOCAN CITY LANDMARK: WITHIN SANGANDAAN PLAZA, A. MABINI PALAWAN PAWNSHOP METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY 368 EDSA, CALOOCAN CITY LANDMARK: FRONT OF MCU (MANILA CENTRAL UNIVERSITY) PALAWAN PAWNSHOP METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY STALL #1, MARIETTA ARCADE, 1107 GE. SAN MIGUEL ST., SANGANDAAN, CALOOCAN LANDMARK: NEAR UNIVERSITY OF CALOOCAN RD PAWNSHOP METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY 149-D AVE., GRACE PARK, CALOOCAN CITY RD PAWNSHOP METRO MANILA CALOOCAN CITY A1 LTL BLDG. CAMARIN RD. COR. SIKATUNA AVE. URDEJA V CARD BANK METRO MANILA LAS PIÑAS CITY BRGY E. ALDANA REAL ST. LAS PIÑAS CITY PALAWAN PAWNSHOP METRO MANILA LAS PIÑAS CITY 407 ALABANG-ZAPOTE RD., TALON 1, LAS PINAS LANDMARK: FRONT OF MOONWALK MARKET PALAWAN PAWNSHOP METRO MANILA LAS PIÑAS CITY 487 ALMANZA GREGORIO AVENUE, LAS PIÑAS CITY LANDMARK: NEAR SM SOUTH MALL PALAWAN PAWNSHOP METRO MANILA LAS PIÑAS CITY 325 DE GUZMAN COMPOUND, REAL ST. PULANG LUPA 1, LASPINAS CITY LANDMARK: NEAR SHELL STATION PALAWAN PAWNSHOP METRO MANILA LAS PIÑAS CITY UNIT H, ZAPOTE-ALABANG RD, PAMPLONA, LAS PIÑAS LANDMARK: NEAR ZAPOTE FLYOVER PALAWAN PAWNSHOP METRO MANILA LAS PIÑAS CITY BLK 2 LOT 12 CAA ROAD, AGUILAR AVE., PULANG LUPA DOS, LAS PINAS CITY LANDMARK: IN FRONT OF MARY QUEEN OF APOSTLES PARISH PALAWAN PAWNSHOP METRO MANILA LAS PIÑAS CITY 400 REAL ST., TALON, LAS PINAS CITY LANDMARK : NEAR PUREGOLD MOONWALK RD PAWNSHOP METRO MANILA LAS PIÑAS CITY BLDG. B, CTC COMM. REAL ST. RD PAWNSHOP METRO MANILA LAS PIÑAS CITY 400 REAL ST. -

Natchez State Park Lake 2021 REEL FACTS Ryan Jones – Fisheries Biologist [email protected] (601) 859-3421

Natchez State Park Lake 2021 REEL FACTS Ryan Jones – Fisheries Biologist [email protected] (601) 859-3421 General Information: Natchez State Park Lake is a 230 acre park lake producing quality bass, crappie, bream, and catfish every year. The lake also holds the state record Largemouth Bass (18.15 lbs.), which was caught in 1992. Location: Approximately 10 miles north of Natchez off State Park Rd. Fishery Management: Largemouth Bass, bream, crappie, and catfish. Lake Depth Map: https://www.mdwfp.com/media/5420/natchez-park-lake.pdf Purchase a Fishing License: https://www.ms.gov/mdwfp/hunting_fishing/ Amenities Regulations Fishing Tips Bream • 1 boat ramp with courtesy • Fishing is not allowed from • Try crickets, red wigglers, piers, parking lot, and the courtesy piers adjacent and wax worms in shallow public restroom to boat ramp. areas along the dam and • 2 handicapped fishing around the cabins. piers • Rod and reel or pole • 50 camping pads with fishing is allowed. No Catfish water/electric hookups, 10 trotlines, FFFD’s, jugs, yo- • Try tightlining liver or blood cabins, and 8 tent sites yo’s, limblines, throwlines, scented bait along deep • 9 hole disc golf course, 6 or set hooks are allowed. drop offs of main lake picnic sites, playground, points and creek channels. pavilion, and nature trail • Sport fishing licenses and fishing permits are Crappie Creel and Size Limits required except on • Fish standing timber and designated days during brush around the main • Bream: 100 per day National Fishing and lake creek channels. Boating Week. Vertical jigging is popular • Catfish: 10 per day with jigs and minnows. -

1St Valley Bank

1ST VALLEY BANK 2015 COMPANY PROFILE WHO WE ARE COMPANY INFORMATION & 1st Valley Bank is a multi-awarded development bank servicing CONTACT DETAILS Regions IX (Zamboanga Peninsula), X (Northern Mindanao), XI (Davao City), Caraga Region and some key cities in the Visayas. 1ST Valley Bank, a Development It has 31 branches, 7 extension offices, and 1 other banking Bank office. Head Office: Carmen, Cagayan de Oro 1st Valley Bank is one of the largest independent developmental Phone Numbers: (88)8584153 banks based in Mindanao. Its focus is to fund development Fax Numbers: (88)8565632 projects and businesses through the provision of loan capital. Email: [email protected] The Bank also offers technical assistance to its borrowers to increase their assurance of success. Annual Income: Total Employees: Total Branches: 31 branches BRIEF HISTORY plus 8 extension offices 1st Valley Bank was formerly known as the Rural Bank of Kapatagan Valley (RUBANKA) first, and then Kapatagan Valley MANAGEMENT DIRECTORY Bank (KVB). It earned its license to operate on November 24, Chief Executive Officer / President 1956 and became the 75th rural bank in the country. On April 5, Atty. Nicolas J. Lim 1957, the Bank has earned its prestigious membership in the Rural Bank Association of the Philippines (RBAP). Executive Vice President Nelson L. Te In April 2004, Kapatagan Valley Bank entered into a Human Resources Executive consolidation agreement with Rural Bank of Sinacaban. On Vivian V. Lim August 30, 2005, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) issued the Certificate of Consolidation and Certificate of Chief of Staff Glenn A. Mendez Incorporation to the merging institutions. -

Electrofishing, Trap Netting and Fisheries Biologists Attempt to Answer This Important Question Negatively Affected

SurveySurvey Says... Says... In Nebraska, much of this attention begins in the form of fish surveys. Commission fisheries biologists essentially conduct two types of surveys. Text and photos by Jeff Kurrus The first, and simpler, method is an angler survey that is used periodically to try and determine how many anglers are accessing a given body of water, how many hours they are fishing, and how many fish are they catching. ...a lot, as far as a fishery is concerned. Anchored in science, fish surveys are an This information is then compared to data from past years to help biologists invaluable part of fisheries management and provide both short- and long-term determine whether any changes need to be made to management practices in place for that particular body of water. estimates regarding the health of a water body. Complementing that type of data are the annual netting surveys conducted on many of Nebraska’s lakes and reservoirs. These surveys, ow’s the fishing?” and “Catching any?” are two of as well as they can, but it’s not always easy. based in scientific theory and empirical data, provide consistent methods for the most asked questions heard on any of Numerous factors can affect the dynamics of a fishery – analyzing a fishery’s health. Nebraska’s approximately 500 public fishing summer and winterkill; overharvest; drought and floods; and Because not all fish use the same type of habitat, however, no single When surveying, scales are taken below the waters. A better question, however, would be too much or not enough aquatic vegetation.