Comparison of a Prepositioned Areal Electrofishing Device and Fixed Underwater Videography for Sampling Riverine Fishes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines for Electrofishing Waters Containing Salmonids Listed Under

National Guidelines for Electrofishing Waters Marine Fisheries Containing Salmonids Listed Under Service the Endangered Species Act June 2000 Purpose and Scope The purpose of this document is to provide guidelines for the safe use of backpack electrofishing in waters containing salmonids listed by the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). It is expected that these guidelines will help improve electrofishing technique in ways which will reduce fish injury and increase electrofishing efficiency. These guidelines and sampling protocol were developed from NMFS research experience and input from specialists in the electrofishing industry and fishery researchers. This document outlines electrofishing procedures and guidelines that NMFS has determined to be necessary and advisable when working in freshwater systems where threatened or endangered salmon and steelhead may be found. As such, the guidelines provide a basis for reviewing proposed electrofishing activities submitted to NMFS in the context of ESA Section 10 permit applications as well as scientific research activities proposed for coverage under an ESA Section 4(d) rule. These guidelines specifically address the use of backpack electrofishers for sampling juvenile or adult salmon and steelhead that are not in spawning condition. Electrofishing in the vicinity of adult salmonids in spawning condition and electrofishing near redds are not discussed as there is no justifiable basis for permitting these activities except in very limited situations (e.g., collecting brood stock, fish rescue, etc.). The guidelines also address sampling and fish handling protocols typically employed in electrofishing studies. While the guidelines contain many specifics, they are not intended to serve as an electrofishing manual and do not eliminate the need for good judgement in the field. -

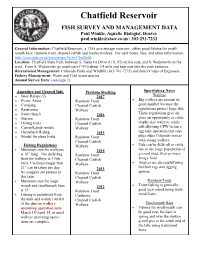

Chatfield Reservoir

Chatfield Reservoir FISH SURVEY AND MANAGEMENT DATA Paul Winkle, Aquatic Biologist, Denver [email protected] / 303-291-7232 General Information: Chatfield Reservoir, a 1355 acre storage reservoir, offers good fishing for small- mouth bass, rainbow trout, channel catfish and trophy walleye. For park hours, fees, and other information: http://cpw.state.co.us/placestogo/Parks/Chatfield Location: Chatfield State Park, between S. Santa Fe Drive (U.S. 85) on the east, and S. Wadsworth on the west. From S. Wadsworth go south past C-470 about 1/4 mile and turn east into the park entrance. Recreational Management: Colorado Parks and Wildlife (303-791-7275) and Army Corps of Engineers. Fishery Management: Warm and Cold water species Annual Survey Data: (see page 2) Amenities and General Info. Previous Stocking Sportfishing Notes Boat Ramps (2) 2017 Walleye Picnic Areas Rainbow Trout Big walleye are present in Camping Channel Catfish good number because the Restrooms Walleye regulations protect large fish. Swim Beach 2016 These regulations give an- Marina Rainbow Trout glers an opportunity to catch Hiking trails Channel Catfish trophy size walleye, while Canoe/Kayak rentals Walleye still allowing CPW to run a Horseback Riding 2015 egg take operation that sup- Model Airplane Field Rainbow Trout plies other Colorado waters Channel Catfish with young walleye. Fishing Regulations Walleye Fish can be difficult to catch Minimum size for walleyes 2014 due to the large population of is 18” long. The daily bag Rainbow Trout gizzard shad, their primary limit for walleye is 3 fish. Channel Catfish forage food. Only 1 walleye longer than Walleye Anglers are successful using 21” can be taken per day. -

Review of Policy, Legal, and Institutional Arrangements for Philippine Compliance with the Wcpf Convention

REVIEW OF POLICY, LEGAL, AND INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR PHILIPPINE COMPLIANCE WITH THE WCPF CONVENTION Jay L. Batongbacal TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. THE WCPF CONVENTION 3 2.1 General Background 3 2.1.1 The Commission 4 2.1.2 The Secretariat and Subsidiary Bodies 5 A. Secretariat 5 B. Other Subsidiary Bodies 6 B.1 Scientific Committee 6 B.2 Technical and Compliance Committee 6 B.3 Northern Committee 7 2.1.3 Decision-making 7 2.1.4 Cooperation with Other Organizations 8 2.1.5 Financial Arrangements 8 2.2 Management Policy in the Convention Area 8 2.2.1 Precautionary Approach 8 2.2.2 Ecosystem-based Approach 9 2.2.3 Compatibility of Measures 10 2.2.4 Due Regard for Disadvantaged and Good Faith 11 2.2.5 Management Actions 11 2.3 Member's Obligations 12 2.3.1 General Obligations 12 2.3.2 Compliance and Enforcement Obligations 13 A. Flag State Obligations 13 B. Boarding and Inspection 14 C. Investigation 15 D. Punitive Measures 17 E. Port State Measures 17 2.4 Conservation and Management Measures 18 2.4.1 Fishing Vessel Registry Standards 18 A. Vessel Marking and Identification 18 B. Authorization to Fish 19 C. Record of Authorized Fishing Vessels 20 D. Commission Vessel Monitoring System 21 E. IUU Vessel 'Blacklisting' 21 F. Charter Notification Scheme 22 G. Vessel Without Nationality 22 2.4.2 Fishing Operation Regulations 23 A. Transhipment 23 B. Gear Restrictions 24 C. Catch Retention 25 D. Area/Season Closures 25 E. Mitigation Measures 26 2.4.3 Species-specific Restrictions 27 2.5 Other 'Soft' Obligations 28 2.6 Peaceful Settlement of Disputes 29 3. -

FISHING NEWSLETTER 2020/2021 Table of Contents FWP Administrative Regions and Hatchery Locations

FISHING NEWSLETTER 2020/2021 Table of Contents FWP Administrative Regions and Hatchery Locations .........................................................................................3 Region 1 Reports: Northwest Montana ..........................................................................................................5 Region 2 Reports: West Central Montana .....................................................................................................17 Region 3 Reports: Southwest Montana ........................................................................................................34 Region 4 Reports: North Central Montana ...................................................................................................44 Region 5 Reports: South Central Montana ...................................................................................................65 Region 6 Reports: Northeast Montana ........................................................................................................73 Region 7 Reports: Southeast Montana .........................................................................................................86 Montana Fish Hatchery Reports: .......................................................................................................................92 Murray Springs Trout Hatchery ...................................................................................................................92 Washoe Park Trout Hatchery .......................................................................................................................93 -

Impacts of Fishing Line and Other Litter by Deborah Weisberg

Impacts of Fishing Line and Other Litter by Deborah Weisberg During cleanup of the North Branch of the Susquehanna River, a canoe barge was crafted and used to transport photo-Melissa Rohm heavy debris out of a shallow water inlet. Dave Miko has seen a lot of strange sights as Division of It has spurred some conservationists to try to avert more Fisheries Management chief for the Pennsylvania Fish & losses. According to trout guide George Daniel of TCO Fly Boat Commission (PFBC). Shop in State College, Trout Unlimited chapters in central But, few compare to the hourglass-shaped trout he has Pennsylvania have stepped up landowner outreach efforts as encountered on streams, where they have grown around fishing pressure mounts on Penn’s Creek, the Little Juniata plastic bottleneck rings that someone tossed into the water. River and other blue-ribbon streams. “I have seen it twice when I was electrofishing, so it On Lake Erie, the Pennsylvania Steelhead Association probably happens even more,” said Miko. “I cut the rings and and other groups make litter pickups and goodwill gestures hoped for the best, but it’s sad and disturbing.” towards landowners a major part of their mission. With More often, angler and boater carelessness takes other PFBC spending millions of dollars to acquire easements on forms, as evidenced by bait cups, plastic water bottles and Elk Creek, Walnut Creek and other popular fisheries, this tangled fishing lines that blight stream banks and lake shores. kind of private-sector support helps lay the groundwork for It takes thousands of years for petroleum-based plastics to future access purchases. -

Fishing for Fairness Poverty, Morality and Marine Resource Regulation in the Philippines

Fishing for Fairness Poverty, Morality and Marine Resource Regulation in the Philippines Asia-Pacific Environment Monograph 7 Fishing for Fairness Poverty, Morality and Marine Resource Regulation in the Philippines Michael Fabinyi Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Fabinyi, Michael. Title: Fishing for fairness [electronic resource] : poverty, morality and marine resource regulation in the Philippines / Michael Fabinyi. ISBN: 9781921862656 (pbk.) 9781921862663 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Fishers--Philippines--Attitudes. Working poor--Philippines--Attitudes. Marine resources--Philippines--Management. Dewey Number: 333.91609599 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Cover image: Fishers plying the waters of the Calamianes Islands, Palawan Province, Philippines, 2009. Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press Contents Foreword . ix Acknowledgements . xiii Selected Tagalog Glossary . xvii Abbreviations . xviii Currency Conversion Rates . xviii 1 . Introduction: Fishing for Fairness . 1 2 . Resource Frontiers: Palawan, the Calamianes Islands and Esperanza . 21 3 . Economic, Class and Status Relations in Esperanza . 53 4 . The ‘Poor Moral Fisher’: Local Conceptions of Environmental Degradation, Fishing and Poverty in Esperanza . 91 5 . Fishing, Dive Tourism and Marine Protected Areas . 121 6 . Fishing in Marine Protected Areas: Resistance, Youth and Masculinity . -

7 JUN 30 PZ 155 of the REPUBLIC of the PHILIPPINES ) FIRST REGULAR SESSION 1 >,E.,I., ' '% SENATE ' ' 4;) ~~~~~Lv~*: Senate Bill No

FOURTEENTH CONGRESS 1 7 JUN 30 PZ 155 OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES ) FIRST REGULAR SESSION 1 >,e.,I., ' '% SENATE ' ' 4;) ~~~~~lV~*: Senate Bill No. 171 , Introduced by Sen. M.A.Madrigal EXPLANATORY NOTE The Tubbataha Reef is located within Central Sulu Sea. It is part of the Sulu West Sea Marine Triangle under the jurisdiction of Cagayancillo, Palawan. It is made up of two atolls, the North Reef and South Reef. The Tubbataha Reef is home to seven (7) species of seagrasses, which are food for the endangered marine turtle, and seventy-one (71) algae, and four hundred seventy-nine species of marine fishes. Eighty-six percent (86%) of the total coral species in the Philippines are found in Tubbataha Reef area. The fish biomass in the Tubbataha Reef is more than average. It is the rookery of twenty-three species of migratory and resident sea birds, some of which is globally threatened. It is a nesting ground for two species of endangered marine turtles. Due to its biodiversity and ecological significance, the Tubbataha Reef Natural Park was declared a protected sanctuary in August 2006 through Presidential Proclamation No. 1126. In line with the State's policy of securing for the Filipino people of present and future generations the perpetual existence of all native plants and animals, it is incumbent upon the Congress to enact a law to provide for the management, protection, sustainable development and rehabilitation of the Tubattaha Reef Natural Park. This shall be established within the framework of the National Integrated Protected Area System (NIPAS) Act, or Republic Act of 7586, while considering the welfare and recognizing the rights of all the communities living therein especially the indigenous peoples. -

Regional Fisheries Livelihood Program (RFLP) (GCP/RAS/237/SPA)

Regional Fisheries Livelihood Program (RFLP) (GCP/RAS/237/SPA) Output 5: Facilitated access to microfinance services for fishers, processors and vendors. FAO-Commissioned APRACA FishFinance Scoping Mission A consolidated report of the results and recommendations of the APRACA National Consultants from the six (6) countries covered by the RFLP. This document is an output from a project funded by the Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores y de Cooperación (MAEC) of Spain and implemented by the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO). The views expressed here are not necessarily those of the MAEC neither of the FAO. Consolidated by: Xavier Tezzo February 2011 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Acronyms.......................................................................................................... 8 List of Figures ............................................................................................................ 11 Currencies ................................................................................................................. 12 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 13 Background ................................................................................................................ 13 Purpose of the scoping mission ................................................................................ 14 Consultancy team and schedule of activities ............................................................ 15 Structure of the report -

Natchez State Park Lake 2021 REEL FACTS Ryan Jones – Fisheries Biologist [email protected] (601) 859-3421

Natchez State Park Lake 2021 REEL FACTS Ryan Jones – Fisheries Biologist [email protected] (601) 859-3421 General Information: Natchez State Park Lake is a 230 acre park lake producing quality bass, crappie, bream, and catfish every year. The lake also holds the state record Largemouth Bass (18.15 lbs.), which was caught in 1992. Location: Approximately 10 miles north of Natchez off State Park Rd. Fishery Management: Largemouth Bass, bream, crappie, and catfish. Lake Depth Map: https://www.mdwfp.com/media/5420/natchez-park-lake.pdf Purchase a Fishing License: https://www.ms.gov/mdwfp/hunting_fishing/ Amenities Regulations Fishing Tips Bream • 1 boat ramp with courtesy • Fishing is not allowed from • Try crickets, red wigglers, piers, parking lot, and the courtesy piers adjacent and wax worms in shallow public restroom to boat ramp. areas along the dam and • 2 handicapped fishing around the cabins. piers • Rod and reel or pole • 50 camping pads with fishing is allowed. No Catfish water/electric hookups, 10 trotlines, FFFD’s, jugs, yo- • Try tightlining liver or blood cabins, and 8 tent sites yo’s, limblines, throwlines, scented bait along deep • 9 hole disc golf course, 6 or set hooks are allowed. drop offs of main lake picnic sites, playground, points and creek channels. pavilion, and nature trail • Sport fishing licenses and fishing permits are Crappie Creel and Size Limits required except on • Fish standing timber and designated days during brush around the main • Bream: 100 per day National Fishing and lake creek channels. Boating Week. Vertical jigging is popular • Catfish: 10 per day with jigs and minnows. -

Electrofishing, Trap Netting and Fisheries Biologists Attempt to Answer This Important Question Negatively Affected

SurveySurvey Says... Says... In Nebraska, much of this attention begins in the form of fish surveys. Commission fisheries biologists essentially conduct two types of surveys. Text and photos by Jeff Kurrus The first, and simpler, method is an angler survey that is used periodically to try and determine how many anglers are accessing a given body of water, how many hours they are fishing, and how many fish are they catching. ...a lot, as far as a fishery is concerned. Anchored in science, fish surveys are an This information is then compared to data from past years to help biologists invaluable part of fisheries management and provide both short- and long-term determine whether any changes need to be made to management practices in place for that particular body of water. estimates regarding the health of a water body. Complementing that type of data are the annual netting surveys conducted on many of Nebraska’s lakes and reservoirs. These surveys, ow’s the fishing?” and “Catching any?” are two of as well as they can, but it’s not always easy. based in scientific theory and empirical data, provide consistent methods for the most asked questions heard on any of Numerous factors can affect the dynamics of a fishery – analyzing a fishery’s health. Nebraska’s approximately 500 public fishing summer and winterkill; overharvest; drought and floods; and Because not all fish use the same type of habitat, however, no single When surveying, scales are taken below the waters. A better question, however, would be too much or not enough aquatic vegetation. -

Electrofishing for Freshwater Fish

Freshwater fish: electrofishing— fixed reach Version 1.1 This specification was prepared by Michael Lake in 2013. Contents Synopsis .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Assumptions .................................................................................................................................... 2 Advantages ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Disadvantages ................................................................................................................................. 4 Suitability for inventory ..................................................................................................................... 5 Suitability for monitoring ................................................................................................................... 5 Skills ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Resources ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Minimum attributes .......................................................................................................................... 7 Data storage ................................................................................................................................... -

Comparison of Day Electrofishing, Night Electrofishing, and Trap Netting for Sampling Inshore Fish in Minnesota Lakes1

Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Special Publication 161, January 2004 COMPARISON OF DAY ELECTROFISHING, NIGHT ELECTROFISHING, AND TRAP NETTING FOR SAMPLING INSHORE FISH IN MINNESOTA LAKES1 Michael C. McInerny and Timothy K. Cross Minnesota Department of Natural Resources 20596 Highway 7 Hutchinson, MN 55350 USA Abstract. -- We compared fish samples collected with pulsed DC boom electrofishing during the day, the same type of electrofishing at night, and trap netting during four sampling periods (spring, early summer, late summer, and fall) in six Minnesota lakes. Night elec- trofishing captured 30 fish species, day electrofishing captured 27 species, and trap nets cap- tured 20 species in these lakes. Four species were captured most frequently with day electrofishing, 13 species were captured most frequently with night electrofishing, and 10 species were captured most frequently with trap nets. Trap nets usually caught larger golden shiner Notemigonus crysoleucas, yellow bullhead Ameiurus natalis, sunfish Lepomis spp., yellow perch Perca flavescens, and walleye Sander vitreus than either type of electrofishing. Both types of electrofishing captured similar sized individuals of all species. Based on catch per sample site, trap netting during spawning, also when aquatic macrophyte densities were low, effectively captured all three bullhead species and both crappie species, but this gear was ineffective for capturing largemouth bass Micropterus salmoides, smallmouth bass M. dolomieu, and all small nongame species during all times of the year. Both types of elec- trofishing were usually more effective in capturing most species during late summer or fall when submergent aquatic macrophyte densities were highest. However, day electrofishing was ineffective for capturing walleye, and both electrofishing times were ineffective in sam- pling either crappie species.