MALAWI Transport Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender Analysis of Maize Post-Harvest Management in Malawi: a Case Study of Lilongwe and Mchinji Districts

Federal Department of Foreign Affairs Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation SDC Swiss Cooperation Office Southern Africa Gender Analysis of Maize Post-Harvest Management in Malawi: A Case Study of Lilongwe and Mchinji districts March 2015 Acknowledgements This study was funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) through the Effective Grain Storage Project (EGSP II). Perspectives shared herein do not reflect the views of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation. The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Centre (CIMMYT) is grateful to the men and women who shared their perspectives in ways that enabled us to understand gender issues around grain post-harvest management in the study districts of Malawi. This report was prepared by Dr. Dyton Duncan Maliro of Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources (LUANAR) in collaboration with Dr. Vongai Kandiwa, CIMMYT Gender Specialist. Table of Contents Executive Summary ..........................................................................................................................v List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. xi List of abbreviations ...................................................................................................................... xii List of local names and terms ....................................................................................................... xiv 1. Background ................................................................................................................................1 -

Review of the Effectiveness of Rail Concessions in the SADC Region

Technical Report: Review of the Effectiveness of Rail Concessions in the SADC Region Larry Phipps, Short-term Consultant Submitted by: AECOM Submitted to: USAID/Southern Africa Gaborone, Botswana March 2009 USAID Contract No. 690-M-00-04-00309-00 (GS 10F-0277P) P.O. Box 602090 ▲Unit 4, Lot 40 ▲ Gaborone Commerce Park ▲ Gaborone, Botswana ▲ Phone (267) 390 0884 ▲ Fax (267) 390 1027 E-mail: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................. 4 2. INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................... 8 2.1 Background .......................................................................................................... 8 2.2 Objectives of Study .............................................................................................. 9 2.3 Study Methodology .............................................................................................. 9 2.4 Report Structure................................................................................................. 10 3. BEITBRIDGE BULAWAYO RAILWAY CONCESSION ............................................. 11 3.1 Objectives of Privatization .................................................................................. 11 3.2 Scope of Railway Privatization ........................................................................... 11 3.3 Mode of Privatization......................................................................................... -

Railways: Looking for Traffi C

Chapter11 Railways: Looking for Traffi c frican railroads have changed greatly stock. Moreover, various confl icts and wars in the past 30 years. Back in the 1980s, have rendered several rail sections unusable. A many railway systems carried a large As a result, some networks have closed and share of their country’s traffi c because road many others are in relatively poor condition, transport was poor or faced restrictive regu- with investment backlogs stretching back over lations, and rail customers were established many years. businesses locked into rail either through Few railways are able to generate signifi - physical connections or (if they were para- cant funds for investment. Other than for statals) through policies requiring them to use purely mineral lines, investment has usually a fellow parastatal. Since then, most national come from bilateral and multilateral donors. economies and national railways have been Almost all remaining passenger services fail liberalized. Coupled with the general improve- to cover their costs, and freight service tariffs ment in road infrastructure, liberalization has are constrained by road competition. More- led to strong intermodal competition. Today, over, as long as the railways are government few railways outside South Africa, other than operated, bureaucratic constraints and lack dedicated mineral lines, are essential to the of commercial incentives will prevent them functioning of the economy. from competing successfully. Since 1993, sev- Rail networks in Africa are disconnected, eral governments in Africa have responded by and many are in poor condition. Although concessioning their systems, often accompa- an extensive system based in southern Africa nied by a rehabilitation program funded by reaches as far as the Democratic Republic of international fi nancial institutions. -

Results of Railway Privatization in Africa

36005 THE WORLD BANK GROUP WASHINGTON, D.C. TP-8 TRANSPORT PAPERS SEPTEMBER 2005 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Results of Railway Privatization in Africa Richard Bullock. Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized TRANSPORT SECTOR BOARD RESULTS OF RAILWAY PRIVATIZATION IN AFRICA Richard Bullock TRANSPORT THE WORLD BANK SECTOR Washington, D.C. BOARD © 2005 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone 202-473-1000 Internet www/worldbank.org Published September 2005 The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. This paper has been produced with the financial assistance of a grant from TRISP, a partnership between the UK Department for International Development and the World Bank, for learning and sharing of knowledge in the fields of transport and rural infrastructure services. To order additional copies of this publication, please send an e-mail to the Transport Help Desk [email protected] Transport publications are available on-line at http://www.worldbank.org/transport/ RESULTS OF RAILWAY PRIVATIZATION IN AFRICA iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface .................................................................................................................................v Author’s Note ...................................................................................................................... -

Port of Maputo, Mozambique

CONFERENCE PROGRAMME Transport Evolution presents 13 - 14 May 2019 | Port of Maputo, Mozambique 25+ expert speakers, including: Osório Lucas Chief Executive Officer, Maputo Port Development Company Col. Andre Ciseau Secretary General, Port Management Association of Eastern & Southern Africa (PMAESA) Clive Smith Chief Executive Officer, Walvis Bay Corridor Group, Namibia Johny Smith Chief Executive Officer, TransNamib Holdings Limited, Namibia Boineelo Shubane Director Operations, Botswana Railways, Botswana Building the next generation of ports and rail in Mozambique Host Port Authority: Supported by: Member of: Organised by: Simultaneous conference translation in English and Portuguese will be provided Será disponibilizada tradução simultânea da conferência em Inglês e Português www.transportevolutionmz.com Welcome to the inaugural Mozambique Ports and Rail Evolution Forum Ports and railways are leading economic engines for Mozambique, providing access to import and export markets, driving local job creation, and unlocking opportunities for the development of the local blue economy. Hosted by Maputo Port Development Company, Mozambique Ports and Rail Evolution prepares the region’s ports and railways for the fourth industrial revolution. Day one of the extensive two-day conference will feature a high level keynote comprising of leading African ports and rail authorities and focus on advancing Intra-African trade. We then explore challenges, opportunities and solutions for improving regional integration and connectivity. Concluding the day, attendees will learn from local and international ports authorities and terminal operators about challenges and opportunities for ports development. Day two begins by looking at major commodities that are driving infrastructure development forward and what types of funding and investment opportunities are available. This is followed by a rail spotlight session where we will learn from local and international rail authorities and operators about maintenance and development projects. -

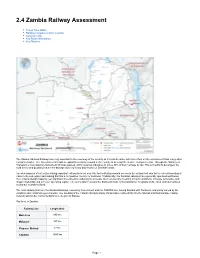

2.4 Zambia Railway Assessment

2.4 Zambia Railway Assessment Travel Time Matrix Railway Companies and Consortia Capacity Table Key Route Information Key Stations The Zambia National Railways are very important to the economy of the country as it is a bulk carrier with less effect on the environment than many other transport modes. The Government intends to expand its railway network in the country to develop the surface transport sector. Through the Ministry of Transport, a new statutory instrument (SI) was passed, which requires industries to move 30% of their carriage by rail. This is in a bid to decongest the road sector and possibly reduce the damage done by heavy duty trucks on Zambian roads. The development of rail routes linking important exit points is not only vital for facilitating smooth access to the outside but also for the overall boosting of trade in the sub-region and making Zambia a competitive country for business. Traditionally, the Zambian railways have generally operated well below their original design capacity, yet significant investment is underway to increase their volumes by investing in track conditions, increase locomotive and wagon availability and increase operating capital. The rail network remains the dominant mode of transportation for goods on the local and international routes but is under-utilized. The main railway lines are the Zambia Railways, owned by Government and the TAZARA line, linking Zambia with Tanzania, and jointly owned by the Zambian and Tanzanian governments. The opening of the Chipata-Mchinji railway link provides connectivity into the Malawi and Mozambique railway network and further connects Zambia to the port of Nacala. -

National Transportation System in the Republic of Zambia

World Maritime University The Maritime Commons: Digital Repository of the World Maritime University World Maritime University Dissertations Dissertations 1990 National transportation system in the Republic of Zambia Febby Mtonga WMU Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Mtonga, Febby, "National transportation system in the Republic of Zambia" (1990). World Maritime University Dissertations. 877. https://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations/877 This Dissertation is brought to you courtesy of Maritime Commons. Open Access items may be downloaded for non- commercial, fair use academic purposes. No items may be hosted on another server or web site without express written permission from the World Maritime University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WMU LIBRARY WORLD MARITIME UNIVERSITY Malmo ~ Sweden THE NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM IN THE REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA by Febby Mtonga Zambia A paper submitted to the faculty of the World Maritime University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of a MASTER OF SCIENCE DEGREE in GENERAL MARITIME ADMINISTRATION The views and contents expressed in this paper reflect entirely those of my own and are not to be construed as necessarily endorsed by the University Signed: Date : 0 5 I 11 j S O Assessed by: Professor J. Mlynarcz] World Maritime University Ilf Co-assessed by: U. 2).i TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 PREFACE i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ii ABBREVIATIONS ... LIST OF MAPS AND APPENDICES iv CHAPTER 1 M • O • o Profile of the Republic of Zambia 1 1.1.0 Geographical Location of Zambia 1.2.0 Population 1.3.0 The Economy 1.3.1 Mining 1.3.2 Agriculture 3 1.3.3 Manufacturing 4 1.3.4 Transportation 7 1. -

Republic of Malawi Diagnostic Trade Integration Study (DTIS) Update

Report No: ACS7534 Public Disclosure Authorized Republic of Malawi Diagnostic Trade Integration Study (DTIS) Update Public Disclosure Authorized Reducing trade costs to promote competitiveness and inclusive growth March 25, 2014 Public Disclosure Authorized AFTP1 AFRICA Public Disclosure Authorized Standard Disclaimer: This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Copyright Statement: The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, http://www.copyright.com/. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA, fax 202-522-2422, e-mail [email protected]. -

ANNEX REPORT Volume

STRATEGIC REVIEW SSATP ANNEX REPORT Volume III NETHERLANDS ECONOMIC INSTITUTE October 2001 This Annex Report (Volume III) is one of the final outputs of the strategic review of the Sub-Saharan Transport Policy Programme (SSATP). In addition to this Annex Report, an Extended Executive Summary (Volume I) and a Final Report (Volume II) have been produced. In the Annex Report the following annexes are included: 1. Terms of Reference 2. References 3. Country Report Côte d’Ivoire 4. Country Report Ethiopia 5. Country report Ghana 6. Country Report Malawi 7. Country Report Mozambique 8. Donors’ Perspective 9. The policy issues 10. Partnerships beyond Africa 11. Review Framework SSATP 12. Expenditures and Budget Assessment 13. SSATP Framework Document 14. UNECA: minutes of meeting Annex 1 Terms of Reference Terms of Reference A. Background To The Review 2001 The Sub-Saharan Africa Transport Policy Program (SSATP) was launched as a joint initiative of the World Bank and the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) to improve transport sector performance by promoting policy reforms and institutional changes. The basic premises of the Program are that: (i) policy reform is essential to obtain improved transport services; and (ii) countries and their development partners need to collaborate within the common framework of policies in the sector. The program has over the last twelve years evolved into a flexible tool for the development of such a framework. SSATP is a broad collaborative effort of national development aid agencies, international agencies (UNDP, ILO and UNCTAD), and African institutions (i.e. UAR, MINCONMAR, PTA), with the World Bank and the ECA acting as the Executing Agencies. -

National Transport Policy

Republic of Malawi NATIONAL TRANSPORT POLICY APRIL 2015 Table of Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................ iii Preface................................................................................................................................ iv List of Acronyms and Abbreviations .................................................................................. v 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background .......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Status of the Transport Sector .............................................................................. 1 1.2.1 National Transport System ........................................................................... 1 1.2.2 Sector Coordination ...................................................................................... 5 1.2.3 Institutional Reformsr ................................................................................... 5 1.2.4 Challenges Facing the Sector ........................................................................ 5 1.3 Linkages with Other Relevant Policies ................................................................ 6 1.4 Performance Constraints ...................................................................................... 7 1.5 Purpose of the Policy........................................................................................... -

Malawi-Zambia

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND NACALA ROAD CORRIDOR DEVELOPMENT PROJECT- PHASE IV COUNTRY: MULTINATIONAL (MALAWI/ ZAMBIA) PROJECT APPRAISAL REPORT OITC DEPARTMENT November 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS I - STATEGIC THRUST & RATIONALE……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..1 1.1 Project linkages with country strategy and objectives……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..1 1.2 Rationale for the Bank's involvement……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..2 1.3 Donors coordination…………………………………………………………………….……………………………………………………………………………………………3 II- PROJECT DECSRIPTION……………………………………………………………..……………………………………………………………………………….4 2.1 Project development objctives components…………………………………………………………...............................................................................4 2.2 Project components…………………………………………………………...............................................................................4 2.3 Technical solution retained and other alternatives explored……………………………………………………………………………………..5 2.4 Project type…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..5 2.5 Project cost and financing arrangments……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..5 2.6 Project's target area and population……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….7 2.7 Particpatory process for project identification, design and implementation…………………………………………………………………………………………8 2.8 Bank Group experience, lessons reflected in project design…………………………………….……………………………………………………………..8 2.9 Key performance indicators………………………...................................................................................................................................................9 -

UNCTAD/LDC/115 20 July 2001

UNCTAD/LDC/115 20 July 2001 ENGLISH ONLY TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT BOARD Fifth Meeting of Governmental Experts from Land-locked and Transit Developing Countries and Representatives of Donor Countries and Financial and Development Institutions New York, 30 July - 3 August 2001 REVIEW OF PROGRESS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF TRANSIT TRANSPORT SYSTEMS IN EASTERN AND SOUTHERN AFRICA Report prepared by InfraAfrica (Pty) Ltd UNCTAD consultant * / _________________ * / The views expressed in this study are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the UNCTAD secretariat or of any official administration. The designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. 2 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 3-4 I. Objectives and scope of report..................................................................................... 4-5 II. Approach and methodology........................................................................................... 5-6 III. Layout of report.................................................................................................................6 IV. Inventory of transit-transport systems and facilities...................................................