“Inside That Fortress Sat a Few Peasant Men, and It Was Half-Made". a Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FOMA Members Honoured!

Issue Number 23: August 2011 £2.00 ; free to members FOMA Members Honoured! FOMA member Anne Wade was awarded the MBE in the Queen’s Birthday Honours for services to the community in Rochester. In June, Anne received a bouquet of congratulations from Sue Haydock, FOMA Vice President and Medway Council Representative. More inside... Ray Maisey, Clock Tower printer became Deputy Mayor of Medway in May. Ray is pictured here If undelivered, please return to: with his wife, Buffy, Deputy Mayoress and FOMA Medway Archives office, member. Civic Centre, More inside... Strood, Rochester, Kent, ME2 4AU. The FOMA AGM FOMA members await the start of the AGM on 3 May 2011 at Frindsbury. Betty Cole, FOMA Membership Secretary, signed members in at the AGM and took payment for the FOMA annual subscription. Pictured with Betty is Bob Ratcliffe FOMA Committee member and President of the City of Rochester Society. April Lambourne’s Retirement The Clock Tower is now fully indexed! There is now a pdf on the FOMA website (www.foma-lsc.org/newsletter.html) which lists the contents of all the issues since Number 1 in April 2006. In addition, each of the past issues now includes a list of contents; these are highlighted with an asterisk (*). If you have missed any of the previous issues and some of the articles published, they are all available to read on the website . Read them again - A Stroll through Strood by Barbara Marchant (issue 4); In Search of Thomas Fletcher Waghorn (1800- 1850) by Dr Andrew Ashbee (issue 6); The Other Rochester and the Other Pocahontas by Ruth Rosenberg-Naparsteck (issue 6); Jottings in the Churchyard of Celebrating April All Saints Frindsbury by Tessa Towner (issue 8), The Skills of the Historian by Dr Lambourne’s retirement from Kate Bradley (issue 9); The Rosher Family: From Gravesend to Hollywood by MALSC at the Malta Inn, Amanda Thomas (issue 9); George Bond, Architect and Surveyor, 1853 to 1914 by Allington. -

First Evidence of Farming Appears; Stone Axes, Antler Combs, Pottery in Common Use

BC c.5000 - Neolithic (new stone age) Period begins; first evidence of farming appears; stone axes, antler combs, pottery in common use. c.4000 - Construction of the "Sweet Track" (named for its discoverer, Ray Sweet) begun; many similar raised, wooden walkways were constructed at this time providing a way to traverse the low, boggy, swampy areas in the Somerset Levels, near Glastonbury; earliest-known camps or communities appear (ie. Hembury, Devon). c.3500-3000 - First appearance of long barrows and chambered tombs; at Hambledon Hill (Dorset), the primitive burial rite known as "corpse exposure" was practiced, wherein bodies were left in the open air to decompose or be consumed by animals and birds. c.3000-2500 - Castlerigg Stone Circle (Cumbria), one of Britain's earliest and most beautiful, begun; Pentre Ifan (Dyfed), a classic example of a chambered tomb, constructed; Bryn Celli Ddu (Anglesey), known as the "mound in the dark grove," begun, one of the finest examples of a "passage grave." c.2500 - Bronze Age begins; multi-chambered tombs in use (ie. West Kennet Long Barrow) first appearance of henge "monuments;" construction begun on Silbury Hill, Europe's largest prehistoric, man-made hill (132 ft); "Beaker Folk," identified by the pottery beakers (along with other objects) found in their single burial sites. c.2500-1500 - Most stone circles in British Isles erected during this period; pupose of the circles is uncertain, although most experts speculate that they had either astronomical or ritual uses. c.2300 - Construction begun on Britain's largest stone circle at Avebury. c.2000 - Metal objects are widely manufactured in England about this time, first from copper, then with arsenic and tin added; woven cloth appears in Britain, evidenced by findings of pins and cloth fasteners in graves; construction begun on Stonehenge's inner ring of bluestones. -

16 Phase 4D Late Medieval and Renaissance Fortification 1350–1600 AD

Metro Cityring – Kongens Nytorv KBM 3829, Excavation Report 16 Phase 4d Late medieval and Renaissance fortification 1350–1600 AD 16.1 Results The presentation of the remains from Phase 4d will be given from two perspectives. Firstly there will be an account of the different feature types – part of a bulwark and the Late medieval moat (Fig. 140 and Tab. 37). After the overall description the features are placed in a structural and historical context. This time phase could have been presented together with either the eastern gate building and/or the Late medieval city wall, but is separated in the report due to the results and dates, interpretations and the general discussion on the changes that have been made on the overall fortification over time. This also goes for the backfilling and levelling of the Late medieval moat which actually should be placed under time Phase 6 (Post medieval fortification and other early 17th century activities), but are presented here due to the difficulties in distinguishing some of these deposits from the usage layers and the fact that these layers are necessary for the discussion about the moat’s final destruction, etc. Museum of Copenhagen 2017 248 Metro Cityring – Kongens Nytorv KBM 3829, Excavation Report Fig. 140. Overview of Late medieval features at Kongens Nytorv. Group Type of feature Subarea Basic interpretation 502976 Timber/planks Trench ZT162033 Bulwark 503806 Cut and fills Station Box Ditch? 450 Construction cut, sedimentation and Several phases Moat, 16th century backfills 560 Dump and levelling layers Phase 5B-2 Moat, 16th century 500913 Timber Phase 5A-1 Wooden plank Tab. -

Gloucestershire Castles

Gloucestershire Archives Take One Castle Gloucestershire Castles The first castles in Gloucestershire were built soon after the Norman invasion of 1066. After the Battle of Hastings, the Normans had an urgent need to consolidate the land they had conquered and at the same time provide a secure political and military base to control the country. Castles were an ideal way to do this as not only did they secure newly won lands in military terms (acting as bases for troops and supply bases), they also served as a visible reminder to the local population of the ever-present power and threat of force of their new overlords. Early castles were usually one of three types; a ringwork, a motte or a motte & bailey; A Ringwork was a simple oval or circular earthwork formed of a ditch and bank. A motte was an artificially raised earthwork (made by piling up turf and soil) with a flat top on which was built a wooden tower or ‘keep’ and a protective palisade. A motte & bailey was a combination of a motte with a bailey or walled enclosure that usually but not always enclosed the motte. The keep was the strongest and securest part of a castle and was usually the main place of residence of the lord of the castle, although this changed over time. The name has a complex origin and stems from the Middle English term ‘kype’, meaning basket or cask, after the structure of the early keeps (which resembled tubes). The name ‘keep’ was only used from the 1500s onwards and the contemporary medieval term was ‘donjon’ (an apparent French corruption of the Latin dominarium) although turris, turris castri or magna turris (tower, castle tower and great tower respectively) were also used. -

A Possible Ring Fort from the Late Viking Period in Helsingborg

A POSSIBLE RING FORT FROM THE LATE VIKING PERIOD IN HELSINGBORG Margareta This paper is based on the author's earlier archaeologi- cal excavations at St Clemens Church in Helsingborg en-Hallerdt Weidhag as well as an investigation in rg87 immediately to the north of the church. On this occasion part of a ditch from a supposed medieval ring fort, estimated to be about a7o m in diameter, was unexpectedly found. This discovery once again raised the question as to whether an early ring fort had existed here, as suggested by the place name. The probability of such is strengthened by the newly discovered ring forts in south-western Scania: Borgeby and Trelleborg. In terms of time these have been ranked with four circular fortresses in Denmark found much earlier, the dendrochronological dating of which is y8o/g8r. The discoveries of the Scanian ring forts have thrown new light on south Scandinavian history during the period AD yLgo —zogo. This paper can thus be regarded as a contribution to the debate. Key words: Viking Age, Trelleborg-type fortress, ri»g forts, Helsingborg, Scania, Denmark INTRODUCTION Helsingborg's location on the strait of Öresund (the Sound) and its special topography have undoubtedly been of decisive importance for the establishment of the town and its further development. Opinions as to the meaning of the place name have long been divided, but now the military aspect of the last element of the name has gained the up- per. hand. Nothing in the find material indicates that the town owed its growth to crafts, market or trade activity. -

Medieval Castle

The Language of Autbority: The Expression of Status in the Scottish Medieval Castle M. Justin McGrail Deparment of Art History McGilI University Montréal March 1995 "A rhesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fu[filment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Am" O M. Justin McGrail. 1995 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1*u of Canada du Canada Aquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie SeMces seMces bibliographiques 395 Wellingîon Street 395, nie Wellingtm ûîtawaON K1AON4 OitawaON K1AON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une Licence non exclusive Licence dowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distniuer ou copies of this thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous papet or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels rnay be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. H. J. B6ker for his perserverance and guidance in the preparation and completion of this thesis. I would also like to recognise the tremendous support given by my family and friends over the course of this degree. -

“Moat” Strategy in Real Estate Warren Buffett Buys Investments with “Economic Moats” in Order to Earn Safer, Higher Returns

HOW TO INVEST IN REAL HOW I LEARNED TO STOP I HAVE EVERY DOLLAR I’VE WHY COMPOUND ARE YOU MISSING ESTATE WITHOUT OWNING STOCK PICKING AND LOVE EARNED IN MY 10 YEAR INTEREST ISN’T AS OPPORTUNITIES TO SAVE REAL ESTATE INDEX FUNDS CAREER POWERFUL AS YOU THINK $100,000+ IN ORDER TO (http://www.investmentzen(h.ctotpm://bwlwogw/.hinovwe-stmentzen(h.ctotpm://bwlwogw/.hinovwe-stmentzen(h.ctotpm://bwlwogw/.ii-nvestmentzenS.cAoVmE P/bENloNgIE/wS?hy- HOME (HTTP://WWW.INVESTMENTZEN.COM/BLOG/) » REAL ESTATE INVESTING (HTTP://WWW.INVESTMENTZEN.COM/BLOG/TOPICS/REAL-ESTATE/) JUNE 26, 2017 How To Use Warren Buffett’s “Moat” Strategy In Real Estate Warren Buffett buys investments with “economic moats” in order to earn safer, higher returns. You can use the same concept to buy protable real estate investments. Here’s how. j Sh3a1re s Tw3e2et b Pin1 a Reddit q Stumble B Pocketz Bu2ff2er h +1 2 k Email o 88 SHARES (https://www.(rhetdtpd:it//.wcowmw/.ssutubmbitl?euurpl=ohnt.tcpo:m//w/swuwb.minivt?eusrtml=hentttpz:e//nw.cwowm.i/nbvloegs/thmoewn-ttzoe-nu.sceo-mwa/brlroegn/-hbouwff-ettots-u-mseo-awta-srrtreant-ebguyf-fetts-moat- RELATED POSTS HOW TO INVEST IN REAL ESTATE WITHOUT OWNING REAL ESTATE (tiewornhoeswi-ta-tritnahlnep-tioavn:e/uelg-/-st)w--t-ww.(ihntvteps:/t/mwewnwtz.einnv.ceostmm/benlotgz/ehno.cwo-m/blog/how- to-invest-in-real-estate- CHAD CARSON without-owning-real- (HTTP://WWW.INVESTMENTZEN.COM/BLOG/AUTHOR/COACHCARSON/) estate/) Real estate investor, world traveler, husband & INVESTING IN REAL ESTATE VS STOCKS: PICKING A SIDE father of 2 (http://www.investmentzen.com/blog/real- (esminhtsovatttaecrpkst:et-/i-/tnvw-gsw-/)w.einstvaetset-mvse-nsttozcekn-.mcoamrk/belto- g/real- investing/) I’m a Warren Buffett nerd. -

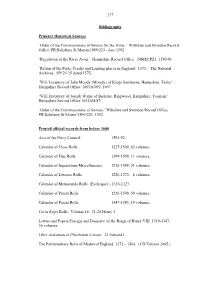

217 Bibliography Primary Historical Sources 'Order Of

217 Bibliography Primary Historical Sources ‘Order of the Commissioners of Sewers for the Avon.’ Wiltshire and Swindon Record Office, PR/Salisbury St Martin/1899/223 - date 1592. ‘Regulation of the River Avon.’ Hampshire Record Office. 24M82/PZ3. 1590-91. ‘Return of the Ports, Creeks and Landing places in England. 1575.’ The National Archives. SP12/135 dated 1575. ‘Will, Inventory of John Moody (Mowdy) of Kings Somborne, Hampshire. Tailor.’ Hampshire Record Office. 1697A/099. 1697. ‘Will, Inventory of Joseph Warne of Bisterne, Ringwood, Hampshire, Yeoman.’ Hampshire Record Office 1632AD/87. ‘Order of the Commissioners of Sewers.’ Wiltshire and Swindon Record Office, PR/Salisbury St Martin/1899/223. 1592. Printed official records from before 1600 Acts of the Privy Council. 1591-92. Calendar of Close Rolls. 1227-1509, 62 volumes. Calendar of Fine Rolls. 1399-1509, 11 volumes. Calendar of Inquisitions Miscellaneous. 1216-1509, 21 volumes. Calendar of Liberate Rolls. 1226-1272, 6 volumes. Calendar of Memoranda Rolls. (Exchequer.) 1326-1327. Calendar of Patent Rolls. 1226-1509, 59 volumes. Calendar of Patent Rolls. 1547-1583, 19 volumes. Curia Regis Rolls. Volume 16. 21-26 Henry 3. Letters and Papers Foreign and Domestic of the Reign of Henry VIII. 1519-1547, 36 volumes. Liber Assisarum et Placitorum Corone. 23 Edward I. The Parliamentary Rolls of Medieval England. 1272 – 1504. (CD Version 2005.) 218 Placitorum in Domo Capitulari Westmonasteriensi Asservatorum Abbreviatio. (Abbreviatio Placitorum.) 1811. Rotuli Hundredorum. Volume I. Statutes at Large. 42 Volumes. Statutes of the Realm. 12 Volumes. Year Books of the Reign of King Edward the Third. Rolls Series. Year XIV. Printed offical records from after 1600 Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, of the Reign of Charles I. -

Warfare in a Fragile World: Military Impact on the Human Environment

Recent Slprt•• books World Armaments and Disarmament: SIPRI Yearbook 1979 World Armaments and Disarmament: SIPRI Yearbooks 1968-1979, Cumulative Index Nuclear Energy and Nuclear Weapon Proliferation Other related •• 8lprt books Ecological Consequences of the Second Ihdochina War Weapons of Mass Destruction and the Environment Publish~d on behalf of SIPRI by Taylor & Francis Ltd 10-14 Macklin Street London WC2B 5NF Distributed in the USA by Crane, Russak & Company Inc 3 East 44th Street New York NY 10017 USA and in Scandinavia by Almqvist & WikseH International PO Box 62 S-101 20 Stockholm Sweden For a complete list of SIPRI publications write to SIPRI Sveavagen 166 , S-113 46 Stockholm Sweden Stoekholol International Peace Research Institute Warfare in a Fragile World Military Impact onthe Human Environment Stockholm International Peace Research Institute SIPRI is an independent institute for research into problems of peace and conflict, especially those of disarmament and arms regulation. It was established in 1966 to commemorate Sweden's 150 years of unbroken peace. The Institute is financed by the Swedish Parliament. The staff, the Governing Board and the Scientific Council are international. As a consultative body, the Scientific Council is not responsible for the views expressed in the publications of the Institute. Governing Board Dr Rolf Bjornerstedt, Chairman (Sweden) Professor Robert Neild, Vice-Chairman (United Kingdom) Mr Tim Greve (Norway) Academician Ivan M£ilek (Czechoslovakia) Professor Leo Mates (Yugoslavia) Professor -

Beowulf and the Sutton Hoo Ship Burial

Beowulf and The Sutton Hoo Ship Burial The value of Beowulf as a window on Iron Age society in the North Atlantic was dramatically confirmed by the discovery of the Sutton Hoo ship-burial in 1939. Ne hÿrde ic cymlīcor cēol gegyrwan This is identified as the tomb of Raedwold, the Christian King of Anglia who died in hilde-wæpnum ond heaðo-wædum, 475 a.d. – about the time when it is thought that Beowulf was composed. The billum ond byrnum; [...] discovery of so much martial equipment and so many personal adornments I never yet heard of a comelier ship proved that Anglo-Saxon society was much more complex and advanced than better supplied with battle-weapons, previously imagined. Clearly its leaders had considerable wealth at their disposal – body-armour, swords and spears … both economic and cultural. And don’t you just love his natty little moustache? xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx(Beowulf, ll.38-40.) Beowulf at the movies - 2007 Part of the treasure discovered in a ship-burial of c.500 at Sutton Hoo in East Anglia – excavated in 1939. th The Sutton Hoo ship and a modern reconstruction Ornate 5 -century head-casque of King Raedwold of Anglia Caedmon’s Creation Hymn (c.658-680 a.d.) Caedmon’s poem was transcribed in Latin by the Venerable Bede in his Ecclesiatical History of the English People, the chief prose work of the age of King Alfred and completed in 731, Bede relates that Caedmon was an illiterate shepherd who composed his hymns after he received a command to do so from a mysterious ‘man’ (or angel) who appeared to him in his sleep. -

History of Lincolnshire Waterways

22 July 2005 The Sleaford Navigation Trust ….. … is a non-profit distributing company limited by guarantee, registered in England and Wales (No 3294818) … has a Registered Office at 10 Chelmer Close, North Hykeham, Lincoln, LN6 8TH … is registered as a Charity (No 1060234) … has a web page: www.sleafordnavigation.co.uk Aims & Objectives of SNT The Trust aims to stimulate public interest and appreciation of the history, structure and beauty of the waterway known as the Slea, or the Sleaford Navigation. It aims to restore, improve, maintain and conserve the waterway in order to make it fully navigable. Furthermore it means to restore associated buildings and structures and to promote the use of the Sleaford Navigation by all appropriate kinds of waterborne traffic. In addition it wishes to promote the use of towpaths and adjoining footpaths for recreational activities. Articles and opinions in this newsletter are those of the authors concerned and do not necessarily reflect SNT policy or the opinion of the Editor. Printed by ‘Westgate Print’ of Sleaford 01529 415050 2 Editorial Welcome Enjoy your reading and I look forward to meeting many of you at the AGM. Nav house at agm Letter from mick handford re tokem Update on token Lots of copy this month so some news carried over until next edition – tokens, nav house description www.river-witham.co.uk Martin Noble Canoeists enjoying a sunny trip along the River Slea below Cogglesford in May Photo supplied by Norman Osborne 3 Chairman’s Report for July 2005 Chris Hayes The first highlight to report is the official opening of Navigation House on June 2nd. -

Anglo–Saxon and Norman England

GCSE HISTORY Anglo–Saxon and Norman England Module booklet. Your Name: Teacher: Target: History Module Booklet – U2B- Anglo-Saxon & Norman England, 1060-88 Checklist Anglo-Saxon society and the Norman conquest, 1060-66 Completed Introduction to William of Normandy 2-3 Anglo-Saxon society 4-5 Legal system and punishment 6-7 The economy and social system 8 House of Godwin 9-10 Rivalry for the throne 11-12 Battle of Gate Fulford & Stamford Bridge 13 Battle of Hastings 14-16 End of Key Topic 1 Test 17 William I in power: Securing the kingdom, 1066-87 Page Submission of the Earls 18 Castles and the Marcher Earldoms 19-20 Revolt of Edwin and Morcar, 1068 21 Edgar Aethling’s revolts, 1069 22-24 The Harrying of the North, 1069-70 25 Hereward the Wake’s rebellion, 1070-71 26 Maintaining royal power 27-28 The revolt of the Earls, 1075 29-30 End of Key Topic 2 Test 31 Norman England, 1066-88 Page The Norman feudal system 32 Normans and the Church 33-34 Everyday life - society and the economy 35 Norman government and legal system 36-38 Norman aristocracy 39 Significance of Odo, Bishop of Bayeux 40 William I and his family 41-42 William, Robert and revolt in Normandy, 1077-80 43 Death, disputes and revolts, 1087-88 44 End of Key Topic 3 test 45 1 History Module Booklet – U2B- Anglo-Saxon & Norman England, 1060-88 2 History Module Booklet – U2B- Anglo-Saxon & Norman England, 1060-88 KT1 – Anglo-Saxon society and the Normans, 1060-66 Introduction On the evening of 14 October 1066 William of Normandy stood on the battlefield of Hastings.