Ideas, Politics and Practices of Integrated Science Teaching in the Global Cold War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of the International Clearinghouse on Science and Mathematics Curricular Developments, 1967

*of REPORT RESUMES ED 011 138 SE 003 T80 REPORT OF THE INTERNATIONAL CLEARINGHOUSE ON SCIENCE AND MATHEMATICS CURRICULAR DEVELOPMENTS, 1967. LOCKARD, J. DAVID AND OTHERS MARYLAND UNIV., COLLEGE PARK, SCIENCE TEACHING CTR AMERICAN ASSN. FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF SCIENCE PUB DATE 67 EDRS PRICE MF -$2.75 HC- $18.00 448P. DESCRIPTORS- *CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT, *COLLEGE SCIENCE, ELEMENTARY SCHOOL SCIENCE, *EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS, *INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION, *MATHEMATICS EDUCATION, *SCIENCE EDUCATION, *SECONDARY SCHOOL SCIENCE, BIOLOGY, BIBLIOGRAPHIES0 CHEMISTRY; EARTH SCIENCE, GENERAL SCIENCE, INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS, PHYSICAL SCIENCES, PHYSICS, NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION, UNESCO, REFORTED IS INFORMATION CONCERNING CURRENT PROJECT GROUPS THAT ARE DEVELOPING SCIENCE AND MATHEMATICS CURRICULAR MATERIALS.PROJECTS FROM THE UNITED STATES AND MORE THAN 30 OTHER COUNTRIES ARE INCLUDED. EACH PROJECT IS LISTED SEPARATELY. NFORMATION FOR EACH PROJECT INCLUDES (1) TITLE, (2) PRINCIPALORIGINATORS, (3) PROJECT DIRECTOR,(4) ADDRESS OF THE PROJECTHEADQUARTERS,(5) PROFESSIONAL STAFF, (61 PROJECT SUPPORT,(7) PURPOSES AND OBJECTIVES,(8) SPECIFIC SUBJECT AND GRAD LEVEL,(9) MATERIALS THAT HAVE BEEN PRODUCED, (10) HOWPROJECT MATERIALS ARE BEING USED, (11) LANGUAGE IN WHICHATERIALS HAVE BEEN WRITTEN, (12) LANGUAGES INTO WHICH MATERIALHAVE BEEN OR WILL BE PRINTED IN TRANSLATIONS, (13) ADDITIONAL MATERIALS PRESENTLY BEING DEVELOPED, (14) MATERIALS AVAILABLE FREER(15) PURCHASABLE MATERIALS, (16) SPECIFIC PLANS FOR EVALUATION OF MATERIALS,. (17) SPECIFIC PLANS FORTEACHER 'PREPARATION, AND (18) FUTURE PLANS. THIS DOCUMENT IS ALSO AVAILABLE AT NO COST (WHILE THE SUPPLY LASTS) FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND, SCIENCE TEACHING CENTER, COLLEGE PARK, MARYLAND 20740. (DS) REPORT OF THE INTERNATIONAL CLEARINGHOUSE ON SCIENCE AND MATHEMATICS CURRICULAR DEVELOPMENTS 1967 COMPILED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF J. DAVID LOCKARD A Joint Project of the Commission on Science Education, Science Teaching Center American Association for the University of Maryland Advancement of Science U.S. -

Albert Vinicio Baez and the Promotion of Science Education in the Developing World 1912–2007

Prospects (2007) 37:369–381 DOI 10.1007/s11125-008-9041-6 PROFILE OF EDUCATORS Albert Vinicio Baez and the promotion of science education in the developing world 1912–2007 Fernando Reimers Published online: 29 April 2008 Ó UNESCO IBE 2008 Alberto Vinicio Baez was a pioneer in the field of international science education. He was a physicist who played a leading role in UNESCO’s efforts to support science education globally. His research in the physics of light led to the development of an X-ray micro- scope and of imaging optics. He participated in projects to improve science education in high schools in the United States in the 1950s, a period of intense interest on this topic. In 1961 he was invited to join UNESCO to establish the Division of Science Education. In this position he wrote numerous papers, organized and participated in regional and international conferences, and studied and supported the development of projects to advance science and technology education in developing countries, with a special focus in secondary schools. The programme established the importance of science education, developed low-cost science kits, films and a structured, high-quality curriculum to support physics teachers in Latin America, chemistry education in Asia, biology education in Africa and mathematics education in the Arab States. Baez’s chief intellectual contributions to the field of science education centered on the development and dissemination of the ideas that it was necessary to democratize access to high-quality education in developing countries, that science education should focus on developing the capabilities needed to solve practical problems, and on the role of inter- disciplinarity and social responsibility as core foundations of science education. -

Equal Opportunity News Garrison EO Upcoming W Ee Kly Energizing Our Nation’S Events N Ew Sle Tte R Community Hispanic Heritage

United States Army Garrison-Ansbach, Equal Opportunity Advisor Office Equal Opportunity News Garrison EO Upcoming W ee kly Energizing Our Nation’s Events N ew sle tte r Community Hispanic Heritage 15-18 Each year, Americans observe Dr. Albert Baez, together with Observance National Hispanic Heritage Month Paul Kirkpatrick, develops the first Se pte mber Date: 14 Oct. Sept. 15 through Oct. 15 to cele- X-ray microscope to observe living 2 015 brate the contributions of Ameri- cells. Baez’s daughter, Joan Baez, Time: Noon to 1 p.m. can citizens whose ancestors came became a world-famous writer, sing- Location: Katterbach H ispa nic er, and a human rights activist. from Spain, Mexico, the Caribbe- Fitness Center H e r ita ge an, Central America, and South Dr. Héctor P. García, a physician Mo nth America. and decorated World War II veter- Keynote Speaker: Ms. America’s diversity has always an, founded the American G.I. Fo- Yvonne Rodriguez been one of our nation’s greatest rum, an organization created to en- There will be lots of strengths. Hispanic Americans sure that Hispanic veterans receive cultural entertainment benefits provided under the G.I. Bill have long played an integral role in and food. This event is America’s rich culture, proud her- of Rights of 1944. free to the community! itage, and the building of this great Macario García becomes the first nation. This year’s theme invites us Mexican national to receive a U.S. to reflect on Hispanic Americans’ Congressional Medal of Honor, yet Visit your local library, vitality and meaningful legacy in was refused service at the Oasis Café located on Bleidorn our Nation’s cultural framework. -

Infinite Skies: in Partnershipwithmetropolitan State Collegeofdenver Denver Publicschools

Infinite Skies: Bessie Coleman, Mae Jemison, and Ellen Ochoa THE ALMA PROJECT A Cultural Curriculum Infusion Model Denver Public Schools In partnership with Metropolitan State College of Denver THE ALMA PROJECT A Cultural Curriculum Infusion Model Infinite Skies: Bessie Coleman, Mae Jemison, and Ellen Ochoa By Barbara J. Williams Grades: 11-12 Implementation Time: 6 weeks Published 2002 Denver Public Schools, Denver, Colorado The Alma Curriculum and Teacher Training Project Loyola A. Martinez, Project Director Denver Public Schools, Denver, Colorado ABOUT THE ALMA PROJECT The Alma Curriculum and Teacher Training Project The Alma Curriculum and Teacher Training Project was made possible with funding from a Goals 2000 Partnerships for Educating Colorado Students grant awarded to the Denver Public Schools in July 1996. The Project is currently being funded by the Denver Public Schools. The intent of the Project is to have teachers in the Denver Public Schools develop instructional units on the history, contributions, and issues pertinent to Latinos and Hispanics in the southwest United States. Other experts, volunteers, and community organizations have also been directly involved in the development of content in history, literature, science, art, and music, as well as in teacher training. The instructional units have been developed for Early Childhood Education (ECE) through Grade 12. As instructional units are developed and field-tested, feedback from teachers is extremely valuable for making any necessary modifications in the topic development of future units of study. Feedback obtained in the spring of 1999, from 48 teachers at 14 sites, was compiled, documented and provided vital information for the field testing report presented to the Board of Education. -

238 President Street House

DESIGNATION REPORT 238 President Street House Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 510 Commission 238 President Street House LP-2612 September 18, 2018 DESIGNATION REPORT 238 President Street House LOCATION Borough of Brooklyn 238 President Street LANDMARK TYPE Individual SIGNIFICANCE A grand Anglo-Italianate style house built circa 1853 that has served as a single-family home, the Brooklyn Deaconess Home of the Methodist Episcopal Church, and the residence of the Baezes, one of Brooklyn’s most prominent Mexican American families of the early-to-mid 20th century. Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 510 Commission 238 President Street House LP-2612 September 18, 2018 238 President Street House, Sarah Moses, LPC 2018 LANDMARKS PRESERVATION COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS Frederick Bland, Vice Chair Sarah Carroll, Executive Director Diana Chapin Lisa Kersavage, Director of Special Projects Wellington Chen Mark Silberman, Counsel Michael Devonshire Kate Lemos McHale, Director of Research Michael Goldblum Jared Knowles, Director of Preservation John Gustafsson Anne Holford-Smith REPORT BY Jeanne Lutfy Michael Caratzas, Research Department Adi Shamir-Baron Kim Vauss EDITED BY Kate Lemos McHale PHOTOGRAPHS BY Sarah Moses Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 510 Commission 238 President Street House LP-2612 September 18, 2018 3 of 33 238 President Street House 238 President Street, Brooklyn Designation List 510 LP-2612 Built: c. 1853 Architect: Not determined; architect of 1897 expansion Woodruff Leeming Landmark Site: Borough of Brooklyn, Tax Map Block 351, Lot 12 Calendared: April 10, 2018 Public Hearing: June 26, 2018 On June 26, 2018, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation of the 238 President Street House and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. -

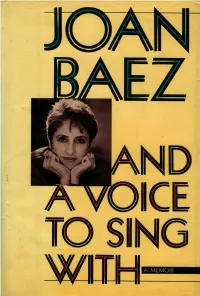

And a Voice to Sing with -- a Memoir, by Joan Baez

AND A VOICE TO SING WITH -- A MEMOIR by Joan Baez © 1987 by Joan Baez Jacket design © 1987 Lawrence Ratzkin Jacket photographs by Matthew Rolston Printed in U.S.A. Copyright © 1987 Simon & Schuster, Inc. For Gabe While you and i have lips and voices which are for kissing and to sing with who cares if some one-eyed son of a bitch invents an instrument to measure Spring with? -- e.e. cummings Table of Contents Front Cover Preface PART ONE: "THE KINGDOM OF CHILDHOOD" 1. "My Memory's Eye" PART TWO: "RIDER, PLEASE PASS BY" 1. "Fill Thee Up My Loving Cup" 2. "Blue Jeans and Necklaces" 3. "Winds of the Old Days" PART THREE: "SHOW ME THE HORIZON" 1. "The Black Angel of Memphis" 2. "Johnny Finally Got His Gun" 3. "Hiroshima Oysters" 4. "For a While on Dreams" 5. "To Love and Music" 6. "I Will Sing to You So Sweet" PART FOUR: "HOW STARK IS THE HERE AND NOW" 1. "Lying in a Bed of Roses" 2. "Silence Is Shame" 3. "Dancing on Our Broken Chains" 4. "Where Are You Now, My Son?" 5. "Warriors of the Sun" PART FIVE: "FREE AT LAST" 1. Renaldo and Who? 2. "Love Song to a Stranger" 3. "No Nos Moveran" 4. "For Sasha" 5. "The Weary Mothers of the Earth" PART SIX: "THE MUSIC STOPPED IN MY HAND" 1. "Blessed Are the Persecuted" 2. "The Brave Will Go" 3. "Motherhood, Music, and Moog Synthesizers" 1975-1979 291 PART SEVEN: "RIPPING ALONG TOWARD MIDDLE AGE" 1. "A Test of Time" 2. -

Joan Baez Ain't Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around

AIN’T GONNA LET NOBODY TURN ME AROUND: JOAN BAEZ RAISES HER VOICE Liz Thomson The Sixties: Take Thirteen Open University, 8 December 2000 Revised December 2003 1 Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around: Joan Baez raises her voice Shortly after Saigon fell on 30 August 1975 and the last American helicopter had lifted unceremoniously off the roof of the US Embassy, 100,000 people filled the Sheep Meadow in New York’s Central Park for a ‘War is Over’ rally. Pete Seeger, Odetta and Joan Baez were among the performers. The event was organised by Phil Ochs, writer of ‘There but for fortune,’ perhaps the most compassionate protest song ever written. It was intended as a celebration of the end of America’s controversial involvement in South-East Asia. Vietnam had galvanised American youth, had been both fuel for the protest movement and the glue that held it together. When the war ‘ended’, most of those who’d sung and spoken so eloquently against its injustices moved on. One who didn’t was Joan Baez. The singer had served two jail terms for ‘aiding and abetting’ draft resisters and had spent 12 days in Hanoi during Nixon’s bombardment of the city in December 1972. Baez had accepted an invitation from the Committee for Solidarity with the American People and joined a small party that included an Episcopalian minister, a Maoist anti-war veteran and Columbia law professor, Telford Taylor, an ex-brigadier general and Nuremburg prosecutor. The Committee’s aim was to maintain friendly relations with the Vietnamese people even as the United States continued to burn their villages. -

Gem of the Mountains

GemGem ofof thethe MountainsMountains The Newsletter of the Boonton Historical Society and Museum August, 2020 210 Main Street, Boonton, New Jersey 07005 ◆ (973) 402-8840 ◆ www.boonton.org ◆ [email protected] Boonton Holds Memorial Day Services And Fourth Of July Celebration The Museum Will Be Reopening By Appointment Only Sundays 1:00 - 4:00 PM The current rules governing museums limits the number of visitors in the building at one time. In addition, face masks and social distancing will be required. Email us at [email protected] to schedule your appointment or leave a message for Veronica at 908-625-6682. Featured in our changing exhibit room is a presentation of the New Jersey Trolley Era. The exhibit includes scale models of various types of trolley cars which operated in New Jersey, along with streetcar memorabilia and artifacts such as an operator’s uniform jacket, hats, badges, books, publications, post cards, photos, videos, lithographs, signs, posters, tickets, lanterns, hardware, and more. Cassidy Davis, representing Boonton Historical Our gift shops will be open offering a wide range of Society, read the entire Declaration of Independence gift items, books by local authors and, of course, a at Boonton's Memorial Day Services and 4th of July selection of Boontonware. ceremony held in Grace Lord Park. - 2 - Spotlight On Arch Bridge Continuing our ongoing series bringing the In May, 2018, we discussed plans to apply for grants museum’s archives to our readers. In this issue the to preserve the Arch Bridge. On August 18 the Town spotlight is on a recent acquisition. -

Race Film Conflict Evades Solution

Chiller at Flicks Tuo former Academy Award Viet Poll to LBJ winners. Bette Davis and Olivia de HariIland, e lane Student Council Wednesday their talents with Joseph Cot- decided to send the results of ten and Agnes Moorehead In the recent campus Vietnam tonight's Friday Flicks chiller. poll to President Johnson. "Hush, Hush, Sweet Char- PARTAN Council voted 9-5-2 in fever DAILY of Including the actual results lotte." The film will be shown at 6:30 and 9:30 in Morris of the poll for all categories Dailey Auditorium. SAN JOSE STATE COLLEGE on the poll form. Vol. 55 .1OP 3 5 SAN JOSE, CALIFORNIA 95114, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 27, 1967 No. 28 Trustees Vote Down Race Film Conflict Collective Bargaining Evades Solution By an overwhelming 14-2 vote, "This decision of the trustees will the California State College Board determine the future action of the Ombudsman J. Benton White lost his first round as a medi- of Trustees turned down an Am- ator of SJS discrimination problems. erican Federation of Teachers Chancellor Glenn S. Durnke's A two-hour closed session between White and the Student (AFT) request for collective bar- proposed state college budget was Initiative I SI), a Mexican-American campus group, failed to gaining at its Pomona meeting approved by the trustees. The yesterday. only change was $86,000 knocked satisfy the minority group that a film produced on SJS (race The AFT previously had threat- out of proposed expansion for bias) does not discrintinate against Mexican-Americans. ened to strike unless a statewide joint doctorate program, accord- The film consists of interviews election were conducted to deter- ing to Jim Coles, public affairs with 11 SJS Negroes and four SJS * * * mine faculty opinion about collec- associate of the Board of Trus- Mexican-Americans. -

Hispanic Heritage Month 15 Sept – 15 Oct 2015

Hispanic Heritage Month 15 Sept – 15 Oct 2015 HISPANIC AMERICANS: ENERGIZING OUR NATION’S DIVERSITY Hispanic Heritage Month 2 Each year, Americans observe National Hispanic Heritage Month from 15 September - 15 October to celebrate the contributions of American citizens whose ancestors came from Spain, Mexico, the Caribbean, Central America, and South America. Hispanic Heritage Month 3 This year’s theme, chosen by the National Council of Hispanic Employment Managers is: “Hispanic Americans: Energizing Our Nation’s Diversity.” Hispanic Heritage Month 4 America’s diversity has always been one of our nation’s greatest strengths. Hispanic Americans have long played an integral role in America’s rich culture, proud heritage, and the building of this great nation. This year’s theme invites us to reflect on Hispanic Americans’ vitality and meaningful legacy in our Nation’s cultural framework. Hispanic Heritage Month 5 As World War II sets in, many Latinos enlist in the U.S. military— proportionately the largest ethnic group serving in the war. Dr. Albert Baez, together with Paul Kirkpatrick, develops the first X-ray microscope to observe living cells. His daughter, Joan Baez, will become a world famous writer, singer, and a human 1940s rights activist. Hispanic Heritage Month 6 Dr. Héctor P. García, a physician and decorated World War II veteran, founds the American G.I. Forum, an organization created to ensure that Hispanic veterans receive benefits provided under the G.I. Bill of Rights of 1944. Macario García becomes the first Mexican national to receive a U.S. Congressional Medal of Honor, yet is refused service at the Oasis Café near his home in Texas. -

Robert Maybury's Contributions to IOCD

International Organization for Chemical Sciences in Development Robert Maybury’s contributions to IOCD Robert Maybury 29 January 1923 – 12 April 2021 Background Robert Harris Maybury (born in Lehighton, Pennsylvania, USA) trained as a chemist, receiving a PhD from Boston University in 1952 in physical chemistry, with Prof. Lowell Coulter. He then held a postdoctoral position in protein chemistry at Harvard University, 1951-53. From 1954 to 1963, he taught analytical and physical chemistry and carried out research in protein physical chemistry at the University of Redlands, California and also worked for a summer period in 1955 in the laboratory of the Nobel laureate Linus Pauling. While at Redlands, Maybury developed interests in encouraging students in research and in communicating chemistry, science and education. In this period, he also began to take note of the importance of science in foreign affairs and the problems faced by scientists in low- and middle-income countries.1 He undertook science missions to Pakistan in 1962 and to Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador and Costa Rica in 1963. When a former colleague and friend at Redlands, Albert Baez,2 moved to UNESCO in Paris and set up a science teaching division there, Maybury accepted the invitation to join him as the team’s chemist in 1963. In 1972-73, he took leave to work for the Ford Foundation on a 1-year study of the Foundation’s projects for improving science education in developing countries, with a particular focus on Argentina, Brazil, Lebanon, the Philippines and Turkey. This led to the publication of a book, Technical Assistance and Innovation in Science Education.3 Following this, he was appointed Deputy Director of the UNESCO Regional Office for Science and Technology for Africa (ROSTA), in Nairobi, Kenya, where he served from 1973 to 1980. -

Idelisa Bonnelly De Calventi Dominican ›› Marine Biology

We believe science creates barriers in aerospace and opportunities and shapes engineering, and helped improve our world. lives of countless communities. Many of these individuals are Countless scientific and still living and working today technological accomplishments across the country and around influence our lives and form the world. the framework for our modern society, and most are led by By making observations, asking individuals whose stories often questions, and striving to go untold. understand how aspects of our world are connected, each of As we honor Hispanic us is an explorer. At the Buffalo Heritage Month, we are Museum of Science, we hope all pleased to highlight people of our guests will be inspired whose groundbreaking to seek out hidden stories, and accomplishments contributed recognize their own potential to scientific understanding, to explore, to discover, and to eradicated disease, broke advance our society. MARIO MOLINA MEXICAN ›› CHEMIST “I am heartened and humbled that I was able to do something that not only contributed to our understanding of atmospheric chemistry, but also had a profound impact on the global environment.” Born in Mexico City, Mario Molina’s 1996, more than 20 years after he early interest in chemistry was first proposed the theory on the supported by his aunt, chemist impacts of CFCs. In 2003, he was Esther Molina. Together, they awarded the Presidential Medal of transformed one of the family’s Freedom for work as a “visionary bathrooms into a working laboratory. chemist and environmental scientist. While a postgraduate at University of California Irving, Molina became interested in chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) their impact on the atmosphere.