Why Economics Is an Evolutionary, Mathematical Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oikos and Economy: the Greek Legacy in Economic Thought

Oikos and Economy: The Greek Legacy in Economic Thought GREGORY CAMERON In the study of the history of economic thought, there has been a tendency to take the meaning of the term “economics” for granted. As a consequence, when considering economic thought in ancient Greece, we turn to what the Greeks said about wealth, about money or about interest. This seems relatively straightforward. Problems emerge when we consider that the term “economics” had a different meaning in ancient Greece than it does today. As a rule, we project back onto history what we mean by “economics” and more or less ignore what it meant during the period in question. On one level, there is nothing wrong with this way of proceeding; after all we have no choice, ultimately, but to study the past with the concepts that are at our disposal. But the procedure can have certain drawbacks. The tendency of positive investigations is that they risk overlooking the kinds of transformations that give rise to our own concerns and even what is essential to our own thought and assumptions. The term “economics” has a long and varied history; the following is a brief attempt to turn things on their head and consider the history of economics not from the perspective of the modern notion of economics, but from the perspective of its ancient Greek ancestor and to begin to indicate the non-obvious ways in which the Greek legacy continues to inform even our most recent economies. As such, while brief mention is made of some modern economic historians, the primary focus is on the meaning of PhaenEx 3, no. -

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics Guoqiang TIAN Department of Economics Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 77843 ([email protected]) This version: August, 2020 1The most materials of this lecture notes are drawn from Chiang’s classic textbook Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, which are used for my teaching and con- venience of my students in class. Please not distribute it to any others. Contents 1 The Nature of Mathematical Economics 1 1.1 Economics and Mathematical Economics . 1 1.2 Advantages of Mathematical Approach . 3 2 Economic Models 5 2.1 Ingredients of a Mathematical Model . 5 2.2 The Real-Number System . 5 2.3 The Concept of Sets . 6 2.4 Relations and Functions . 9 2.5 Types of Function . 11 2.6 Functions of Two or More Independent Variables . 12 2.7 Levels of Generality . 13 3 Equilibrium Analysis in Economics 15 3.1 The Meaning of Equilibrium . 15 3.2 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Linear Model . 16 3.3 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Nonlinear Model . 18 3.4 General Market Equilibrium . 19 3.5 Equilibrium in National-Income Analysis . 23 4 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra 25 4.1 Matrix and Vectors . 26 i ii CONTENTS 4.2 Matrix Operations . 29 4.3 Linear Dependance of Vectors . 32 4.4 Commutative, Associative, and Distributive Laws . 33 4.5 Identity Matrices and Null Matrices . 34 4.6 Transposes and Inverses . 36 5 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra (Continued) 41 5.1 Conditions for Nonsingularity of a Matrix . 41 5.2 Test of Nonsingularity by Use of Determinant . -

Aristotle & Locke: Ancients and Moderns on Economic Theory & The

Xavier University Exhibit Honors Bachelor of Arts Undergraduate 2015-4 Aristotle & Locke: Ancients and Moderns on Economic Theory & the Best Regime Andrew John Del Bene Xavier University - Cincinnati Follow this and additional works at: http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/hab Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Ancient Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Del Bene, Andrew John, "Aristotle & Locke: Ancients and Moderns on Economic Theory & the Best Regime" (2015). Honors Bachelor of Arts. Paper 9. http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/hab/9 This Capstone/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Bachelor of Arts by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Aristotle & Locke: Ancients and Moderns on Economic Theory & the Best Regime Andrew John Del Bene Honors Bachelor of Arts – Senior Thesis Project Director: Dr. Timothy Quinn Readers: Dr. Amit Sen & Dr. E. Paul Colella Course Director: Dr. Shannon Hogue I respectfully submit this thesis project as partial fulfillment for the Honors Bachelor of Arts Degree. I dedicate this project, and my last four years as an HAB at Xavier University, to my grandfather, John Francis Del Bene, who taught me that in life, you get out what you put in. Del Bene 1 Table of Contents Introduction — Philosophy and Economics, Ancients and Moderns 2 Chapter One — Aristotle: Politics 5 Community: the Household and the Πόλις 9 State: Economics and Education 16 Analytic Synthesis: Aristotle 26 Chapter Two — John Locke: The Two Treatises of Government 27 Community: the State of Nature and Civil Society 30 State: Economics and Education 40 Analytic Synthesis: Locke 48 Chapter Three — Aristotle v. -

Mathematical Economics - B.S

College of Mathematical Economics - B.S. Arts and Sciences The mathematical economics major offers students a degree program that combines College Requirements mathematics, statistics, and economics. In today’s increasingly complicated international I. Foreign Language (placement exam recommended) ........................................... 0-14 business world, a strong preparation in the fundamentals of both economics and II. Disciplinary Requirements mathematics is crucial to success. This degree program is designed to prepare a student a. Natural Science .............................................................................................3 to go directly into the business world with skills that are in high demand, or to go on b. Social Science (completed by Major Requirements) to graduate study in economics or finance. A degree in mathematical economics would, c. Humanities ....................................................................................................3 for example, prepare a student for the beginning of a career in operations research or III. Laboratory or Field Work........................................................................................1 actuarial science. IV. Electives ..................................................................................................................6 120 hours (minimum) College Requirement hours: ..........................................................13-27 Any student earning a Bachelor of Science (BS) degree must complete a minimum of 60 hours in natural, -

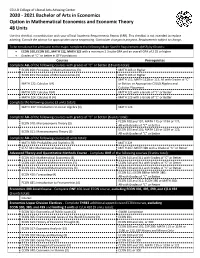

2020-2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical

CSULB College of Liberal Arts Advising Center 2020 - 2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical Economics and Economic Theory 48 Units Use this checklist in combination with your official Academic Requirements Report (ARR). This checklist is not intended to replace advising. Consult the advisor for appropriate course sequencing. Curriculum changes in progress. Requirements subject to change. To be considered for admission to the major, complete the following Major Specific Requirements (MSR) by 60 units: • ECON 100, ECON 101, MATH 122, MATH 123 with a minimum 2.3 suite GPA and an overall GPA of 2.25 or higher • Grades of “C” or better in GE Foundations Courses Prerequisites Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (18 units total): ECON 100: Principles of Macroeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher ECON 101: Principles of Microeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher MATH 111; MATH 112B or 113; All with Grades of “C” MATH 122: Calculus I (4) or Better; or Appropriate CSULB Algebra and Calculus Placement MATH 123: Calculus II (4) MATH 122 with a Grade of “C” or Better MATH 224: Calculus III (4) MATH 123 with a Grade of “C” or Better Complete the following course (3 units total): MATH 247: Introduction to Linear Algebra (3) MATH 123 Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (6 units total): ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 310: Microeconomic Theory (3) All with Grades of “C” or Better ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 311: Macroeconomic Theory (3) All with -

Introduction to the Elgar Companion to Economics and Philosophy John B

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Economics Faculty Research and Publications Economics, Department of 1-1-2004 Introduction to The Elgar Companion to Economics and Philosophy John B. Davis Marquette University, [email protected] Alain Marciano Université de Reims Champagne Ardenne Jochen Runde University of Cambridge Published version. "Introduction," in The Elgar Companion to Economics and Philosophy. Eds. John B. Davis, Alain Marciano and Jochen Runde. Chelthenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2004: xii-xxvii. DOI. © 2004 Edward Elgar Publishing. Used with permission. Introduction John Davis, Alain Marciano and Jochen Runde The closing decades of the twentieth century saw a dramatic increase in interest in the role of philosophical ideas in economics. The period also saw a significant expansion in scholarly investigation into the different connections between economics and philosophy, as seen in the emergence of new journals, professional associations, conferences, seminar series, websites, research networks, teaching methods, and interdisciplinary collaboration. One of the results of this set of developments has been a remarkable distillation in thinking about philosophy and economics around a number of key subjects and themes. The goal of this Companion to Economics and Philosophy is to exhibit and explore a number of these areas of convergence. The volume is accordingly divided into three parts, each of which highlights a leading area of scholarly concern. They are: political economy conceived as political philosophy, the methodology and epistemology of economics, and social ontology and the ontology of economics. The authors of the chapters in the volume were chosen on the basis of their having made distinctive and innovative contributions to their respective areas of expertise. -

The Rise and Fall of Walrasian General Equilibrium Theory: the Keynes Effect

The Rise and Fall of Walrasian General Equilibrium Theory: The Keynes Effect D. Wade Hands Department of Economics University of Puget Sound Tacoma, WA USA [email protected] Version 1.3 September 2009 15,246 Words This paper was initially presented at The First International Symposium on the History of Economic Thought “The Integration of Micro and Macroeconomics from a Historical Perspective,” University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, August 3-5, 2009. Abstract: Two popular claims about mid-to-late twentieth century economics are that Walrasian ideas had a significant impact on the Keynesian macroeconomics that became dominant during the 1950s and 1060s, and that Arrow-Debreu Walrasian general equilibrium theory passed its zenith in microeconomics at some point during the 1980s. This paper does not challenge either of these standard interpretations of the history of modern economics. What the paper argues is that there are at least two very important relationships between Keynesian economics and Walrasian general equilibrium theory that have not generally been recognized within the literature. The first is that influence ran not only from Walrasian theory to Keynesian, but also from Keynesian theory to Walrasian. It was during the neoclassical synthesis that Walrasian economics emerged as the dominant form of microeconomics and I argue that its compatibility with Keynesian theory influenced certain aspects of its theoretical content and also contributed to its success. The second claim is that not only did Keynesian economics contribute to the rise Walrasian general equilibrium theory, it has also contributed to its decline during the last few decades. The features of Walrasian theory that are often suggested as its main failures – stability analysis and the Sonnenschein-Mantel-Debreu theorems on aggregate excess demand functions – can be traced directly to the features of the Walrasian model that connected it so neatly to Keynesian macroeconomics during the 1950s. -

Nine Lives of Neoliberalism

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) Book — Published Version Nine Lives of Neoliberalism Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) (2020) : Nine Lives of Neoliberalism, ISBN 978-1-78873-255-0, Verso, London, New York, NY, https://www.versobooks.com/books/3075-nine-lives-of-neoliberalism This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/215796 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative -

Econ5153 Mathematical Economics

ECON5153 MATHEMATICAL ECONOMICS University of Oklahoma, Fall 2014 Tuesday and Thursday, 9-10:15am, Cate Center CCD1 338 Instructor: Qihong Liu Office: CCD1 426 Phone: 325-5846 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tuesday and Thursday, 1:30-2:30pm, and by appointment Course Description This is the first course in the graduate Mathematical Economics/Econometrics sequence. The objective of this course is to acquaint the students with the fundamental mathematical techniques used in modern economics, including Matrix Algebra, Optimization and Dynam- ics. Upon completion of the course students will be able to set up and analytically solve constrained and unconstrained optimization problems. The students will also be able to solve linear difference equations and differential equations. Textbooks Required: Simon and Blume: Mathematics for Economists, W.W.Norton, 1994. Other useful books available on reserve at Bizzell: Chiang and Wainwright: Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, McGraw-Hill, Fourth Edition, 2005. Darrell A. Turkington: Mathematical Tools for Economics, Blackwell Publishing, 2007. Avinash Dixit: Optimization in Economic Theory, Oxford University Press, Second Edition, 1990. Michael D. Intriligator: Mathematical Optimization and Economic Theory, Prentice-Hall, 1971. Assessment Grades are based on homework (15%), class participation (10%), two midterm exams (20% each) and final exam (35%). You are encouraged to form study groups to discuss homework and lecture materials. All exams will be in closed-book forms. Problem Sets Several problem sets will be assigned during the semester. You will have at least one week to complete each assignment. Late homework will not be accepted. You are allowed to work 1 with other students in this class on the problem sets, but each student must write his or her own answers. -

Paul Samuelson's Ways to Macroeconomic Dynamics

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Boianovsky, Mauro Working Paper Paul Samuelson's ways to macroeconomic dynamics CHOPE Working Paper, No. 2019-08 Provided in Cooperation with: Center for the History of Political Economy at Duke University Suggested Citation: Boianovsky, Mauro (2019) : Paul Samuelson's ways to macroeconomic dynamics, CHOPE Working Paper, No. 2019-08, Duke University, Center for the History of Political Economy (CHOPE), Durham, NC This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/196831 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Paul Samuelson’s Ways to Macroeconomic Dynamics by Mauro Boianovsky CHOPE Working Paper No. 2019-08 May 2019 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3386201 1 Paul Samuelson’s ways to macroeconomic dynamics Mauro Boianovsky (Universidade de Brasilia) [email protected] First preliminary draft. -

Mathematical Economics

ECONOMICS 113: Mathematical Economics Fall 2016 Basic information Lectures Tu/Th 14:00-15:20 PCYNH 120 Instructor Prof. Alexis Akira Toda Office hours Tu/Th 13:00-14:00, ECON 211 Email [email protected] Webpage https://sites.google.com/site/aatoda111/ (Go to Teaching ! Mathematical Economics) TA Miles Berg, Econ 128, [email protected] (Office hours: TBD) Course description Carl Friedrich Gauss said mathematics is the queen of the sciences (and number theory is the queen of mathematics).1 Paul Samuelson said economics is the queen of the social sciences.2 Not surprisingly, modern economics is a highly mathematical subject. Mathematical economics studies the mathematical foundations of economic theory in the approach known as the Arrow-Debreu model of general equilibrium. Partial equilibrium (things like demand and supply curves), which you have probably learned in Econ 100ABC, considers each market separately. General equilibrium (GE for short), on the other hand, considers the economy as a whole, taking into account the interaction of all markets. Econ 113 is probably the most mathematically advanced undergraduate course of- fered at UCSD Economics, but it should have a high return. In the course, we will develop a mathematical model of classical economic thoughts like Bentham's \greatest happiness principle" and Smith's \invisible hand", and prove theorems. Then we will apply the theory to international trade, finance, social security, etc. Time permitting, I will talk about my own research. Prerequisites A year of calculus and a year of upper division microeconomic theory (at UCSD these courses are Math 20ABC and Economics 100ABC) are required. -

Economics and Neoliberalism 25/11/05

essay for After Blair: Politics After the New Labour Decade, forthcoming summer 2006 Economics and Neoliberalism 25/11/05 Edward Fullbrook Neoliberalism is the ideology of our time. And of New Labour and Tony Blair. What happens after Blair becomes seriously interesting if we suppose that within the Labour Party Neoliberalism could be dethroned. Although this event hardly appears immanent, it could be brought forward if the nature and location of the breeding ground of the Neoliberal beast became public knowledge. For a quarter of a century people to the left of what was once a staunchly right-wing position (too rightwing for the rightwing of the Labour Party) have been struggling against Neoliberalism with ever diminishing success. This failure has taken place despite much cogent analysis of the sociological and geopolitical forces fuelling the Neoliberal conquest. The working assumption has been that if Neoliberalism’s books could be opened so that the world could see who its real winners and losers were and the extent of their winnings and loses, then citizens would see the light and politicians of good will would repent and political process would once again enter into a progressive era. This essay breaks with that tradition. While I wholeheartedly agree that the analysis described above is a necessary condition for stopping Neoliberalism, I am no less certain that it is not by itself a sufficient condition. Understanding the consequences of Neoliberalism is not enough. We also must understand where this intellectual poison comes from and the primary channel by which it continues to be injected into the body politic.