Saudi National Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saudi-Yemen Airspace Update Written by David Mumford | 17 March, 2021

Saudi-Yemen Airspace Update written by David Mumford | 17 March, 2021 Houthi drone and missile attacks on targets in Saudi Arabia are increasing. These continue to be a persistent threat to ops to Saudi airports, and for overflights of the OEJD/Jeddah FIR. The most significant risk is in the south of the country along the border with Yemen, but OERK/Riyadh and OEJN/Jeddah airports have also been targeted several times over the past year. OEJN/Jeddah Airport closed temporarily on March 7 following multiple attempted drone attacks. Saudi media reported dozens of drones were intercepted in their airspace, and the US Embassy also issued a statement. OERK/Riyadh Airport was targeted in June 2020 and again in October. Much of the information comes from state media and cannot always be independently verified. Back in 2017, a New York Times investigation suggested that at least one of the most high-profile attacks from that year may not have been “shot-down” or intercepted by Saudi defense systems at all. Saudi Arabia Airspace Risk Long-standing airspace warnings are in place for Saudi Arabia, although the US has not issued any so far. Germany and Canada warn of a risk to landing anywhere in the country, but particularly along the border with Yemen in the southwest part of the OEJD/Jeddah FIR. France has issued similar advice, with the specific warning not to operate to OEAB/Abha, OEGN/Jazan, OENG/Nejran, OESH/Sharurah, OEWD/Wadi Al Dawasir and OEBH/Bisha airports. For more info, check SafeAirspace.net Watch out for ESCAT You might know this as SCATANA. -

Saudi Military Forces and Development: Challenges & Reforms

CSIS_______________________________ Center for Strategic and International Studies 1800 K Street N.W. Washington, DC 20006 (202) 775-3270 Access: Web: CSIS.ORG Contact the Author: [email protected] & [email protected] Saudi Military Forces and Development: Challenges & Reforms Anthony H. Cordesman and Nawaf Obaid Center for Strategic and International Studies Working Draft: May 30, 2004 Please note that this document is a working draft and will be revised regularly as part of the CSIS Saudi Arabia Enters the 21st Century Project. It is also being used by the authors to develop an analysis for the Geneva Center on Security Policy. To comment, or to Cordesman: The Security Apparatus in Saudi Arabia 6/1/04 Page ii provide suggestions and corrections to the authors, please e-mail them at [email protected], [email protected] and [email protected]. Cordesman: The Security Apparatus in Saudi Arabia 6/1/04 Page iii I. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................................................... 1 II. THE SAUDI SECURITY APPARATUS AND SAUDI MILITARY FORCES.................................................... 2 THE LEADERSHIP OF THE SAUDI SECURITY APPARATUS ............................................................................ 3 THE IMPORTANCE OF CONSENSUS AND CONSULTATION ............................................................................ 4 THE LEADERSHIP OF THE SAUDI MILITARY FORCES.................................................................................. -

Saudi 28 Pages & 911 Report 14.9.16

Saudi Arabia and 9/11: Establishing the Truth Behind the Release of the 28 Pages and the “Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act” By Anthony H. Cordesman Update: September 14, 2016 Please provide comments to [email protected] Cover: DoD photo by Master Sgt. Ben Bloker, U.S. Air Force Saudi Arabia and the Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Attack 14/9/16 2 Saudi Arabia and the Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act President Obama has made it clear that he intends to veto the legislation the House passed on September 9, 2016 that would allow families of those killed in the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks to sue Saudi Arabia for any role its officials played in the terrorist attack. He should veto the bill and the Congress should pause and not override that veto. It is all too easy to understand anger the families and survivors of those who were victims on 9/11 feel, and the desire they have to find someone to punish and blame and for some compensation for their losses. It is equally easy to understand the mixed motives of a Congress caught up in the politics of tenth anniversary of the attack, an election year, and the desire not to seem soft on terrorism. Saudi Arabia is also one of America’s most difficult strategic partners for Americans to understand, and its progress, reforms, and strategic importance are often badly understated. It is easier to focus on the fact it is an Islamic state at a time when extremist threats like ISIS, Al Qaida, and the Taliban, than deal with the complicated security issues in the Gulf region and the fact the U.S. -

Briefing Paper

European Multinationals briefing paper Yemen: Fear of Failure Ginny Hill Middle East and North Africa Programme | January 2010 | MENAP BP 2010/01 Summary points Yemen presents a potent combination of problems for policy-makers confronting the prospect of state failure in this strategically important Red Sea country. It is the poorest state in the Arab world, with high levels of unemployment, rapid population growth and dwindling water resources. President Saleh faces an intermittent civil war in the north, a southern separatist movement and resurgent terrorist groups. Following the 2009 merger of al-Qaeda in Yemen and Saudi Arabia, Yemen has become the new centre of gravity for al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. The underlying drivers for future instability are economic. The state budget is heavily dependent on revenue from dwindling oil supplies. Yemen’s window of opportunity to shape its own future and create a post-oil economy is narrowing. Western governments need to work towards an effective regional approach with the member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council, in particular Saudi Arabia. Future instability in Yemen could expand a lawless zone stretching from northern Kenya, through Somalia and the Gulf of Aden, to Saudi Arabia. Piracy, organized crime and violent jihad would escalate, with implications for the security of shipping routes, the transit of oil through the Suez Canal and the internal security of Yemen’s neighbours. This is an updated version of the Briefing Paper published in November 2008 (MEP BP 08/03). www.chathamhouse.org.uk Yemen: Fear of Failure page 2 The situation in Yemen: January 2010 update In the 14 months since the first edition of this Briefing Paper was written, the challenges facing Yemen have intensified. -

Variability of Wintertime Surface Air Temperature Over the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Atmospheric and Climate Sciences, 2012, 2, 307-321 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/acs.2012.23028 Published Online July 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/acs) Variability of Wintertime Surface Air Temperature over the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Hosny Mohamed Hasanean, Abdel Rahman Khalaf Al-Khalaf Department of Meteorology, Faculty of Meteorology, Environment, and Arid Land Agriculture, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, KSA Email: [email protected], [email protected] Received January 22, 2012; revised March 17, 2012; accepted April 17, 2012 ABSTRACT Variability of wintertime surface air temperature (SAT) in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) is studied. The study is based on time series over thirty one years in length (1978-2008). For the analysis, we use the coefficient of variability (COV) Mann-Kendal statistical test, running mean and cumulative annual mean (CAM). The coefficient of variability (COV) for wintertime SAT decreases gradually from the north to the south of KSA. The higher values for COV occur in northern and northeastern KSA; there are due to the effect of the traveling Mediterranean depressions and their inter- action with the inverted-V shape trough of the Sudan low. The relationship between COV and latitude is highly signifi- cant, while with longitude it is not significant. The Mann-Kendal statistical test illustrates that positive trends (warming) in wintertime SAT series occurs over the all stations, and that the trends are significant at middle and southern regions of KSA. Recent warming has only occurred during the last two decades at most stations. While cooling in the winter- time SAT appears for the short period of about 5 years, 1978-1983 and 1988-1992. -

Neolithic Period, North-Western Saudi Arabia

NEOLITHIC PERIOD, NORTH-WESTERN SAUDI ARABIA Khalid Fayez AlAsmari PhD UNIVERSITY OF YORK ARCHAEOLOGY SEPTEMBER 2019 Abstract During the past four decades, the Neolithic period in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) had received little academic study, until recently. This was due to the previous widely held belief that the Arabian Peninsula had no sites dating back to this time period, as well as few local researchers and the scarcity of foreign research teams. The decline in this belief over the past years, however, has led to the realisation of the importance of the Neolithic in this geographical part of the world for understanding the development and spread of early farming. As well as gaining a better understanding of the cultural attribution of the Neolithic in KSA, filling the chronological gaps in this historical era in KSA is vital, as it is not well understood compared to many neighbouring areas. To address this gap in knowledge, this thesis aims to consider whether the Northwest region of KSA was an extension of the Neolithic developments in the Levant or an independent culture, through presenting the excavation of the Neolithic site of AlUyaynah. Despite surveys and studies that have been conducted in the KSA, this study is the first of its kind, because the site "AlUyaynah", which is the focus of this dissertation, is the first excavation of a site dating back to the pre-pottery Neolithic (PPN). Therefore, the importance of this study lies in developing an understanding of Neolithic characteristics in the North-Western part of the KSA. Initially, the site was surveyed and then three trenches were excavated to study the remaining levels of occupation. -

Infrastructure Sector: Overview and Commercial Prospects in Saudi Arabian and U.S

2017 INDUSTRY SECTOR REPORT Infrastructure Sector: Overview and Commercial Prospects in Saudi Arabian and U.S. Construction, Real Estate, and Transport www.us-sabc.org Disclaimer The information that is published in this report was analyzed and compiled from sources believed to be accurate and reliable during the time of publication. The U.S.-Saudi Arabian Business Council accepts no liability for any loss or damage resulting from errors or omissions due to human or mechanical error in any part of this report. The U.S.-Saudi Arabian Business Council provides all information without any warranty. © 2017 The U.S.-Saudi Arabian Business Council. All rights reserved. Neither this publication nor any part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the U.S.-Saudi Arabian Business Council. Reports are published quarterly by the U.S.-Saudi Arabian Business Council, 8081 Wolftrap Road, Suite 300, Vienna, VA 22182. 2 U.S.-Saudi Arabian Business Council Table of Contents 4 Executive Summary SAUDI ARABIAN MARKET 6 Trends in Contracts 7 Growing Value of Infrastructure 8 Government Infrastructure Goals and Financing 9 Infrastructure Objectives through Vision 2030 and the NTP 10 Government Bodies Involved in the Infrastructure Sector 11 Private Sector Initiatives 12 Oil Revenues and Government Projects 14 Financing 15 Regional Trends in Contracts Awarded 16 Domestic and Foreign Firms Involved in Saudi Arabian Infrastructure 20 Macroeconomic Trends 22 Housing Market 24 Transportation 27 Tourism Construction 29 Building Automation 29 Construction Supply Chain for Raw Materials 31 Labor 33 Real Estate 36 Infrastructure Projects in Energy 39 Industrial Infrastructure Projects 40 Special Projects 41 SME’s 41 Restarting Stalled Projects 42 Construction of Social Facilities 42 Commercial Construction U.S. -

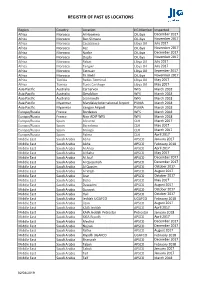

Register of IJS Locations V1.Xlsx

REGISTER OF PAST IJS LOCATIONS Region Country Location JIG Member Inspected Africa Morocco Al Hoceima OiLibya December 2017 Africa Morocco Ben Slimane OiLibya November 2017 Africa Morocco Casablanca Libya Oil July 2017 Africa Morocco Fez OiLibya November 2017 Africa Morocco Nador OiLibya December 2017 Africa Morocco Oujda OiLibya November 2017 Africa Morocco Rabat Libya Oil July 2017 Africa Morocco Tangier Libya Oil July 2017 Africa Morocco Tetouan Libya Oil Sepember 2017 Africa Morocco Tit Melil OiLibya November 2017 Africa Tunisia Rades Terminal Libya Oil May 2017 Africa Tunisia Tunis Carthage Libya Oil May 2017 Asia Pacific Australia Carnarvon WFS March 2018 Asia Pacific Australia Geraldton WFS March 2018 Asia Pacific Australia Learmouth WFS March 2018 Asia Pacific Myanmar Mandalay International Airport PUMA March 2018 Asia Pacific Myanmar Yangon Airport PUMA March 2018 Europe/Russia France Bordeaux WFS March 2018 Europe/Russia France Nice ADIP WFS WFS March 2018 Europe/Russia Spain Alicante CLH March 2017 Europe/Russia Spain Barcelona CLH May 2017 Europe/Russia Spain Malaga CLH March 2017 Europe/Russia Spain Palma CLH April 2017 Middle East Saudi Arabia Abha APSCO January 2017 Middle East Saudi Arabia Abha APSCO February 2018 Middle East Saudi Arabia Al Ahsa APSCO April 2017 Middle East Saudi Arabia Al Baha APSCO May 2017 Middle East Saudi Arabia Al Jouf APSCO December 2017 Middle East Saudi Arabia Al Qaisumah APSCO December 2017 Middle East Saudi Arabia Al Qassim APSCO October 2017 Middle East Saudi Arabia Al Wajh APSCO August 2017 -

Mansouri Full Thesis (Final Version 31-10-13)

Carbon Management for Sustainable Development: An examination of potential transition paths for the Saudi Arabian ‘national system of innovation’ towards a cleaner energy economy Submitted by: Noura Youssef Mansouri This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the full requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. School of Engineering and Materials Science Queen Mary, University of London London, United Kingdom Supervisor: Professor T. Alexander (publishes as T. Korakianitis) Secondary Supervisor: Professor R. J. Crookes 1 In the name of Allah, the Entirely Merciful, the Especially Merciful (Quran 1:1). Corruption has appeared throughout the land and sea by [reason of] what the hands of people have earned so He may let them taste part of [the consequence of] what they have done that perhaps they will return [to righteousness] (Quran 30:41). Indeed, we offered the Trust to the heavens and the earth and the mountains, and they declined to bear it and feared it; but man [undertook to] bear it. Indeed, he was unjust and ignorant (Quran 33:72). He said, "O my people, have you considered: if I am upon clear evidence from my Lord and He has provided me with a good provision from Him? And I do not intend to differ from you in that which I have forbidden you; I only intend reform as much as I am able. And my success is not but through Allah. Upon him I have relied, and to Him I return (Quran 11:88). 2 Dedication and Memoriam He is the Ever-Living; there is no deity except Him, so call upon Him, [being] sincere to Him in religion. -

2 Mid Fasid Table Cns 4

4 TABLE CNS 4- SURVEILLANCE SYSTEMS - 4 - 2 Country/Location G ATS Units Served PSR Coverage SSR (A/C/S) Coverage ADS-B ADS-C SMR PRM Remarks A of PSR of SSR (NM) (NM) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 AFGHANISTAN BAHRAIN Bahrain Bahrain ACC I 80 MI(A/C) 250 Bahrain APP Bahrain ACC F(A/C/S) 250 Bahrain APP <2005 EGYPT Cairo Cairo ACC I 200 MI(A/C) 250 MOD-S IS Cairo APP I 70 I(A/C) 100 PLANNED (TBD) Cairo APP/TMA F<2002 60 MF (A/C) 250 Hurghada Hurghada ACC I MI (A/C) 250 Hurghada ACC I MI(A/C) 250 Hurghada APP I 60 Mersa Matruh Mersa Matruh ACC MI(A/C) 250 Aswan Aswan ACC I MI(A/C) 250 Aswan ACC F<2002 MF(A/C) 250 Aswan APP <2002 60 Asyut Asyut ACC I 250 MI(A/C) 250 Luxor Luxor ACC MI(A/C) 250 Luxor APP I 60 Sharm El Sheikh Sharm El Sheikh ACC MI(A/C) 250 MID FASID Sharm El Sheikh APP I 60 MID FASID Country/Location G ATS Units Served PSR Coverage SSR (A/C/S) Coverage ADS-B ADS-C SMR PRM Remarks A of PSR of SSR (NM) (NM) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Borg El Arab Borg El Arab ACC F (A/C) 250 < 2002 Borg El Arab APP F<2002 60 El Arish El Arish ACC F (A/C) 250 < 2002 El Arish APP F<2002 60 Taba Taba ACC F (A/C) 250 < 2002 Taba APP F<2002 60 IRAN Shiraz Shiraz APP I 80 I (A/C/S) 250 Tehran / Mehrabad Mehrabad APP I 80 I (A/C/S) 250 Ahwaz Tehran ACC MI (A/C/S) 250 < 2000 Iran Shahr Tehran ACC F (A/C/S) 250 < 2002 Jiroft Tehran ACC MI (A/C/S) 250 2001 Lar Tehran ACC MI (A/C/S) 250 < 2001 MI (A/C/S) Mashhad Tehran ACC 250 < 2001 MI (A/C/S) 4 Draz-now (Gorgan) Tehran ACC 250 - <2002 4 - 3 F(A/C/S) Tabas Tehran ACC < 2002 250 4 - Country/Location G ATS -

Overview and Highlights of Consultation Actions Plan & Customer Engagement

OVERVIEW AND HIGHLIGHTS OF JEDDAH FIR ICAO MIDANPIRG ATM SG/5 1 - 4 Dec 2019 Aqaba, Jordan “Managing sky, Securing lives” Contents • Current status • Recent implementations • Ongoing implementations and targets • Updates on ASBU ICAO MIDANPIRG ATM SG/5, Aqaba, Jordan, 1-4 Dec 2019 MainAir NavigationTitle Header Services Certificate ICAO MIDANPIRG ATM SG/5, Aqaba, Jordan, 1-4 Dec 2019 MainATM /Title airspace Header scope City Province ICAO IATA Airport name 1 Dammam Eastern OEDF DMM King Fahd International Airport 2 Jeddah Makkah (Mecca) OEJN JED King Abdulaziz International Airport 3 Riyadh Riyadh OERK RUH King Khalid International Airport 4 Medina (Madinah) Al Madinah OEMA MED Prince Mohammad Bin Abdulaziz International Airport 5 Abha 'Asir OEAB AHB Abha Regional Airport 6 Buraidah Al-Qassim OEGS ELQ Prince Nayef Bin Abdulaziz Regional Airport 7 Jizan (Gizan) Jizan OEGN GIZ Jizan Regional Airport 8 Ha'il Ha'il OEHL HAS Ha'il Regional Airport 9 Tabuk Tabuk OETB TUU Tabuk Regional Airport 10 Ta'if Makkah (Mecca) OETF TIF Ta'if Regional Airport 11 Gassim Gassim OEGS ELQ Prince Naif Bin Abdulaziz airport 12 Yanbu Al Madinah OEYN YNB Yanbu Airport 13 NEOM Bay NEOM OENN NUM NEOM Bay airport 14 Al Bahah (Al-Baha) Al Bahah OEBA ABT Al-Baha Domestic Airport 15 Al-Hofuf, Al-Ahsa Eastern OEAH HOF Al-Ahsa Domestic Airport 16 Al-Jawf Al Jawf OESK AJF Al-Jawf Domestic Airport 17 Al Wajh Tabuk OEWJ EJH Al Wajh Domestic Airport 18 Arar Northern Borders OERR RAE Arar Domestic Airport 19 Bisha 'Asir OEBH BHH Bisha Domestic Airport 20 Dawadmi Riyadh OEDW -

Annual Report 1436H / 1437H 2015

Annual Report www.citc.gov.sa 1436 - 1437 2015 The Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques King Salman bin Abdulaziz His Royal Highness His Royal Highness Prince Mohamad bin Naif bin Abdulaziz Prince Mohamad bin Salman bin Abdulaziz Crown Prince & Deputy Prime Minister Second Deputy Prime Minister Deputy Crown Prince Table of Contents Chairman’s Statement 10 6. Studies 74 Governor’s Statement 12 6.1 Update of the Market Definition, Designation and 74 Dominance Report for the ICT Sector 6.2 Study of the Telecommunication and Information 74 Technology Market in the Kingdom 6.3 Status of ICT in the Kingdom 76 1. Executive Summary 16 7. Growth and Indicators 2. Regulatory Framework 22 of the ICT Sector in the Kingdom 82 3. CITC Strategy (2016-2020) 26 7-1 Mobile Telecommunications Market 82 7-2 Fixed Telephony Market 83 7-3 Broadband Market 84 7-4 Internet Services 86 4. Current Situation 32 7-5 Telecom Services Sector Revenues 87 7-6 International Internet Bandwidth 88 7-7 Domain Names Registered in the Kingdom 88 5. Main Activities and Achievements 40 7-8 ICT Contribution to the National Economy 89 5.1 Licensing of ICT Services 40 5.2 Consumer Protection 46 8. Appendices 5.3 Regulating the ICT Sector 53 94 5.4 Management of Scarce Resources 57 5.5 Universal Service Fund (USF) 66 Appendix A: Decisions of the Board of Directors 94 Appendix B: CITC ebsites 98 Appendix C: Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct 100 Appendix D: CITC Financial Accounts 102 10 ole roaan penetraton rate o te 34oueol populaton teledensity of fixed ontruton o te teleounaton