Wearing History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dossie Easton ; Janet W Hardy the Ne� to © 2003 by Dossie Easton and Janet W

THE NEW Dossie Easton ; Janet W Hardy the ne� To © 2003 by Dossie Easton and Janet W. Hardy All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in newspaper, magazine, radio, television or Internet reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording or by information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher. Cover design: DesignTribe Cover illustration: Fish Published in the United States by Greenery Press, 3403 Piedmont Ave. #301, Oakland,CA 94 611,www .greenerypress.com. ISBN 1-8901 59-36-0 Readers should be aware that BDSM, like all sexual activities, carries an inherent risk ofphysical and/oremot ional injury. While we believe that following the guidelines set forth in this book will minimize that potential, the writers and publisher encourage you to be aware that you are taking some risk when you decide to engage in these activities, and to accept personal responsibility forthat risk. In acting on the information in this book, you agree to accept thatinformation as is and with allfau lts. Neither the authors, the publisher, nor anyone else associated with the creation or sale of this book is responsible for any damage sustained. CONTENTS Foreword: Re-Visioning ............................................ i 1. Hello Again! ............ .............................. .. .... ... ....... 1 2. What Is It About Topping, Anyway? ....................... 9 3. What Do Tops Do? ................ ...................... ........ 21 interlude 1 ....... ... .......... ..... ... ... .. .... ........... ... 33 4. Rights and Responsibilities ... ....... ................ .... 37 5. How Do Yo u Learn To Do This Stuff?. .. ............... 49 interlude 2 .. ...... .. ... ......... .. ................ ....... 57 6. Soaring Higher ...................... ................... ... ...... .. 61 7. BDSM Ethics ................... -

GLBT Historical Society Archives

GLBT Historical Society Archives - Periodicals List- Updated 01/2019 Title Alternate Title Subtitle Organization Holdings 1/10/2009 1*10 #1 (1991) - #13 (1993); Dec 1, Dec 29 (1993) 55407 Vol. 1, Series #2 (1995) incl. letter from publisher @ditup #6-8 (n.d.) vol. 1 issue 1 (Win 1992) - issue 8 (June 1994 [2 issues, diff covers]) - vol. 3 issue 15 10 Percent (July/Aug 1995) #2 (Feb 1965) - #4 (Jun 1965); #7 (Dec 1965); #3 (Winter 1966) - #4 (Summer); #10 (June 1966); #5 (Summer 1967) - #6 (Fall 1967); #13 (July 1967); Spring, 1968 some issues incl. 101 Boys Art Quarterly Guild Book Service and 101 Book Sales bulletins A Literary Magazine Publishing Women Whoever We Choose 13th Moon Thirteenth Moon To Be Vol. 3 #2 (1977) 17 P.H. fetish 'zine about male legs and feet #1 (Summer 1998) 2 Cents #4 2% Homogenized The Journal of Sex, Politics, and Dairy Products One issue (n.d.) 24-7: Notes From the Inside Commemorating Stonewall 1969-1994 issue #5 (1994) 3 in a Bed A Night in the Life 1 3 Keller Three Keller Le mensuel de Centre gai&lesbien #35 (Feb 1998), #37 (Apr 1998), #38 (May 1998), #48 (May 1999), #49 (Jun 1999) 3,000 Eyes Are Watching Me #1 (1992) 50/50 #1-#4 (June-1995-June 1996) 6010 Magazine Gay Association of Southern Africa (GASA) #2 (Jul 1987) - #3 (Aug 1987) 88 Chins #1 (Oct 1992) - #2 (Nov 1992) A Different Beat An Idea Whose Time Has Come... #1 (June 3, 1976) - #14 (Aug 1977) A Gay Dragonoid Sex Manual and Sketchbook|Gay Dragonoind Sex A Gallery of Bisexual and Hermaphrodite Love Starring the A Dragonoid Sex Manual Manual|Aqwatru' & Kaninor Dragonoid Aliens of the Polymarinus Star System vol 1 (Dec 1991); vol. -

Dossie Easton

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs On tops, bottoms and ethical sluts: The place of BDSM and polyamory in lesbian and gay psychology Journal Item How to cite: Barker, Meg (2005). On tops, bottoms and ethical sluts: The place of BDSM and polyamory in lesbian and gay psychology. Lesbian and Gay Psychology Review, 6(2) pp. 124–129. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c [not recorded] Version: [not recorded] Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://www.bps.org.uk/pss/pss_review/pss_review_home.cfm Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Focus on Activism On ‘tops’, ‘bottoms’ and ‘ethical sluts’: The place of SM and polyamory in lesbian and gay psychology Meg Barker in conversation with Dossie Easton In a recent issue of the Lesbian & Gay Psychology Review (Barker, 2004) I interviewed a leading bi activist about the place of bisexuality in the UK and in academic research, but bi communities are not the only ones to be under-represented within psychological writing on sexualities. My own research focuses on polyamory or poly (‘a relationship orientation that assumes that it is possible [and acceptable] to love many people and to maintain multiple intimate and sexual relationships’, Uriel, Haritaworn, Lin & Klesse, 2003, p.126) and SM (sadomasochism, usually encompassing any consensual exchange of power and/or pain). -

Dossie Easton ; Janet W Hardy ,', "

THE NEW Dossie Easton ; Janet W Hardy ,', " , ,' " ""�' ,>" • � " ,¥ - , " '.'" '.:( >� .- " "," ' � © 2001 by Dossie Easton and Janet W. Hardy All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in newspaper, magazine, radio, television or Internet reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording or by information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher. Cover design: DesignTribe Cover illustration: Fish Published in the United States by Greenery Press, 1447 Park Ave., Emeryville, CA 94608, www.greenerypress.com. ISBN 1-890159-35-2 Readers should be aware that BDSM like all sexual activities, carries an inherent risk o/physical and/or emotional injury. While we believe that following the guidelines set forth in this book will minimize that potential, the writers and publisher encourage you to be aware that you are taking some risk when you decide to engage in these activities, and to accept personal responsibilityfor that risk. In acting on the information in this book, you agree to accept that informationas is and with allfoults. Neither the authors, the publisher, nor anyone else associated with the creation or sale o/this book is responsible for any damage sustained. TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword .................................................................... i 1. Introducing Ourselves . ......................................... ... 1 Wh o Are We?. ... ... .. ................... .... ..... ... ... .... 2 Wh o Are You?................ ................ .. .............. ...... 11 Reclaiming Our Greed. ........ .................... ......... .. 16 PART ONE: SKILLS ................................................. 17 2. What Kind of Player Are Yo u, Anyway?................... 19 Th e "Fu ll-Power Bottom" . ...... ............... ............... 23 Bridging the Gap Between Fa ntasy and Reality . ...... 28 3. Staying Safe and Happy .......................................... -

LGBTQ Timeline

Follow the Yellow Brick Road: Re-Learning Consent from Our ForeQueers Timeline 1917: Individuals considered to be “psychopathically inferior,” including LGBT people, are banned from entering the US. 1921: US Naval report on entrapment of “perverts” within its ranks. In 1943, the US military officially bans gays and lesbians from serving in the Armed Forces. 1924: The Society for Human Rights, an American homosexual rights organization founded by Henry Gerber, is established in Chicago. It is the first recognized gay rights organization in the US. A few months after being chartered, the group ceased to exist in the wake of the arrest of several of the Society's members. 1935: “Successful” electric shock therapy treatment of homosexuality is reported at American Psychological Association meeting. 1950: The Mattachine Society, founded by Harry Hay and a group of Los Angeles male friends, is formed to protect and improve the rights of homosexuals. 1955: The Daughters of Bilitis (DOB), the first lesbian rights organization in the US, forms in San Francisco. It is conceived as a social alternative to lesbian bars, which were considered illegal and thus subject to raids and police harassment. It lasted for fourteen years and became a tool of education for lesbians, gay men, researchers, and mental health professionals. As the DOB gained members, their focus shifted to providing support to women who were afraid to come out, by educating them about their rights and gay history. 1963: Gay man, African-American civil rights and nonviolent movement leader Bayard Rustin is the chief organizer of the March on Washington. -

BDSM:Kink Resources

BDSM/Kink Resources Healthcare KINK-AWARE PROFESSIONALS (KAP) The KAP is a directory of professionals in the medical, legal and other professional fields who are knowledgeable and sensitive to diverse sexualities. ST JAMES INFIRMARY The St. James Infirmary provides social and healthcare services for sex workers. Sex Addicts Anonymous (SAA) SAA is a twelve-step organization that provides support and help for people struggling with sex http://www.kinkabuse.com Education and Advocacy SOCIETY OF JANUS The society of Janus is an all-volunteer San Francisco non-profit devoted to the art of safe, consensual and non-exploitative BDSM. DOMSUB.INFO Domsub.info is an excellent resource site for Dominant / submissive relationships, providing articles and information, FAQ, glossary and definitions, training tools, and advice on relationships. ARMORY WORKSHOP SERIES The Armory Workshop series is an educational program organized by Kink.com to bring in educators from around the country to talk about subjects like dirty talk, anal play and rope- rigging in a frank and blunt way. THE EULENSPIEGEL SOCIETY TES is a New York-based not-for-profit organization located in NYC which promotes sexual liberation for all adults, especially for people who enjoy consensual BDSM. CENTER FOR SEX AND CULTURE The Center for Sex and Culture is a non-profit educational and advocacy organization based in San Francisco. For decades, the Center has worked to preserve the history of our communities as well as disseminate information about sexuality, sexual health and safer sex. NATIONAL COALITION OF SEXUAL FREEDOM The NCSF is committed to creating a political, legal and social environment in the US that advances equal rights for consenting adults who engage in alternative sexual and relationship expressions. -

On Tops, Bottoms and Ethical Sluts: the Place of BDSM and Polyamory In

Focus on Activism On ‘tops’, ‘bottoms’ and ‘ethical sluts’: The place of SM and polyamory in lesbian and gay psychology Meg Barker in conversation with Dossie Easton In a recent issue of the Lesbian & Gay Psychology Review (Barker, 2004) I interviewed a leading bi activist about the place of bisexuality in the UK and in academic research, but bi communities are not the only ones to be under-represented within psychological writing on sexualities. My own research focuses on polyamory or poly (‘a relationship orientation that assumes that it is possible [and acceptable] to love many people and to maintain multiple intimate and sexual relationships’, Uriel, Haritaworn, Lin & Klesse, 2003, p.126) and SM (sadomasochism, usually encompassing any consensual exchange of power and/or pain). These sexual identities or practices are found across bisexual, lesbian, gay male and heterosexual groups. However, there is little psychological literature considering the experiences, understandings or needs of people in these communities. Rodriguez Rust (2000) and Sedgwick (1990) argue that we tend to focus on gender as the only characteristic relevant to sexuality. SM and polyamory both suggest the need for a broader understanding of sexuality encompassing factors such as: the relative power of those involved, the physical acts being carried out, and the number of people taking part. Both SM and polyamory challenge many of the ideals of conventional heterosexuality including monogamy, traditional notions of ‘the couple’, and the purposes of - and roles within – sex: for example, male activity and female passivity. Dossie Easton is one of the most prolific writers on the subjects of polyamory and SM. -

LIL V Program Book

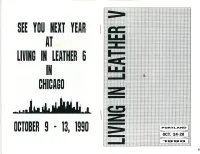

TABLE OF CONTENTS General Information ORGASM Our Name Savs It All! Conference Director: NLA Affrliates SANDMUTOPIA Sallee Huber NLA Chapters SandMutopia CommitteeChair: S and M Utopia George Nelson NLA : Statement of Purpose Suppll'Co. National Co-Chairs: NLA Membership Application ) Jim Richardsi Judy Tallwing McCarthey Special Thanks Electrotorturc Audio Tapes Sounds Magazines N. A. C. Listing Memorial Catl'rctcrs Vicleos Bondage Books Mr. & Ms. NLA: Jan Lyon/ Advertising Leather Drummer Guy Baldwin Latex Mach High Spots: Wayne Gloege CBT DungeonMaster Keynote Speaker: Troy Perry Tit Torture Sandmutopia Guardian Slater/Mains Award: Pat Catifia/ Chuck Renslow Visit us rvhen in San Francisco: - 2{ Shotrvell, San Francisco, CA (.il5) 252-r r95 Workshop Presentors Crcrlit Cartl Orrlers (ihtlly Acccptctl by 'l'clr:¡:lrorre Weekend Schedule C orn pu1=r l'.lodem Usersl Join forces with Local Talent BBS. (41 5) 83i-79=5 l¿r 2l hour access to our catalog. Non.subscribers use 'Drumrn=r' as your password. Workshop Schedule To be on our mailing list, send 53 to: FO Eox 11314, San Franclsco, CA 94101-1314. Art Show Exhibitors CITY: STATE: ZtP Ey ry {ræ bå þçi{ t..eüry rft iEffirt 2l y.rr. ol ¡g.: Mr. & Ms. NLA Contest GENERAL INFORMATION CONFERENCE DIRECTOR As v,e gather in Portla¡xl to celcbrate tiving In læatherV, PHOTOGRAPHY POLICY it seems appropriate toconsider the past, present, and future of what we mean by,,Living In Private photography: Please limit your pictures to peoplesyou know or people who have kåther." As with Ttþs, supersorvls, and other etr'ents given you their permission. -

Leather Times News from the Leather Archives & Museum Spring 2004

Leather Times News from the Leather Archives & Museum Spring 2004 Inside: Gayle Rubin on the history of Samois Leather Colors Art by Etienne and the Hun Capital Campaign LA&M and the Chicago Library System and more! In this issue: Samois.......p. 3 6418 North Greenview Ave., Chicago, Illinois 60626 USA In Memory: Tel: 773.761.9200 Fax: 773.381.4657 Thom Gunn www.leatherarchives.org ...................p. 7 Visiting the LA&M LA&M staff Our True Col- Open visiting hours are: Rick Storer - ors: The [email protected] History and Thursday 12 p.m. to 8 p.m. Executive Director Evolution of Saturday 12 noon to 3 p.m. Backbatch Sunday 12 noon to 3 p.m. Natalie - Insignias ...p. 8 Admission is free, donations are appreciated [email protected] Chief Librarian Requests to see the museum at other times and In Memory: requests to conduct research in the LA&M archives justin tanis - Alan Selby can be arranged by contacting the LA&M. [email protected] .................p. 11 Newsletter Editor Donations and Tax Deductions Jeff Wirsing - LA&M Collec- [email protected] tion News The Leather Archives & Museum is recognized as Facilities Manager .................p. 11 tax exempt under the US Internal Revenue Service section 501c(3). Donations are deductible from your Federal Income tax, subject LA&M Joins to IRS deducation regulations. Chicago Librar- ies ...........p. 12 I would like to make a donation to the Leather Archives & Museum. Thank yous Name: and donor Club or Organization: corrections Address: ...............p. 12 City, State/Province, Postal Code: I represent Thank you! Phone: An individual Fax: Donor Updates An Organization E-mail: .................p. -

Author's Foreword

Gay San Francisco: Eyewitness Drummer 83 Foreword by the Author SOME DANCE TO REMEMBER. SOME DON’T. Toward an Autobiography of Drummer Magazine “Of course I have no right whatsoever to write down the truth about my life, involving as it naturally does the lives of so many other people, but I do so urged by a necessity of truth-telling, because there is no living soul who knows the complete truth; here, may be one who knows a section; and, there, one who knows another section; but to the whole picture not one is initi- ated.” — Vita Sackville-West, Portrait of a Marriage LET’S START AT THE VERY BEGINNING . MY ZERO DEGREES OF SEPARATION (MAP INCLUDED) Allegedly. In the vertigo of memory, I write these eyewitness objective notes and subjective opinions allegedly, because I can only analyze events, manu- scripts, and how we people all seemed together, and not the true hearts of persons. As I said to Proust nibbling on his madeleine, “How pungent is the smell of old magazines.” Drummer is the Rosetta Stone of leather heritage. Drummer published its first issue June 1975. What happened next depends on whom you ask. Before history defaults to fable, I choose to write down my oral eye- witness testimony. Readers might try to understand the huge task of writing history that includes the melodrama of one’s own life lived in the first post-Stonewall decade of gay publishing and gay life. The Titanic 1970s were the Gay Belle Epoque of the newly possible. ©Jack Fritscher, Ph.D., All Rights Reserved—posted 05-05-2017 HOW TO LEGALLY QUOTE FROM THIS BOOK 84 Jack Fritscher, Ph.D. -

Consent Culture and Community in Feminism and BDSM

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2017 Histories of Consent: Consent Culture and Community in Feminism and BDSM Amanda Meltsner University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Meltsner, Amanda, "Histories of Consent: Consent Culture and Community in Feminism and BDSM" (2017). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 203. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/203 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Histories of Consent: Consent Culture and Community in Feminism and BDSM Amanda Meltsner University of Vermont Honors College 5/1/2017 1 Table of Contents Introduction 2 Methodology 4 Definitions and Descriptions 4 A Brief and Incomplete History of BDSM, With Assorted Add Ons 13 Beginnings 13 Leather: Bars, Clubs, and the Scene 15 Writings and Community 19 The Internet and Kink Community 26 Third Wave Feminism 32 Consent: A History, a Discourse 38 Kink and Consent 40 Origins 42 Academia 50 Feminist Understandings of Consent 53 Comparisons 60 Fifty Shades of Grey: Debates, Connections, and Progress 63 Critiques and Critics 64 Conclusion 78 Acknowledgements 80 References 81 2 Introduction This work aims to explore the conversations and disagreements between pro-kink and anti-kink feminists in the world of feminist writing from the early days of BDSM communities through the publication of Fifty Shades of Grey. -

The Debate on Lesbian Sadomasochism: a Discourse Analysis

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-1991 The Debate on Lesbian Sadomasochism: A Discourse Analysis Gudbjorg Ottosdottir Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons Recommended Citation Ottosdottir, Gudbjorg, "The Debate on Lesbian Sadomasochism: A Discourse Analysis" (1991). Master's Theses. 977. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/977 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DEBATE ON LESBIAN SADOMASOCHISM: A DISCOURSE ANALYSIS by Gudbjorg Ottosdottir A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 1991 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. THE DEBATE ON LESBIAN SADOMASOCHISM: A DISCOURSE ANALYSIS Gudbjorg Ottosdottir, M.A. Western Michigan University, 1991 This study examines an issue debated within the U.S. lesbian community since the mid-1970s, lesbian sadomasochism. The issue has been whether sadomasochism is consistent with lesbian feminism, a political ideology which has much shaped lesbian identity and community. The claims and counter-claims made about lesbian sadomasochism are analyzed, as are the underlying ideologies and their relationship to general lesbian political and cultural history. It is argued that the debate is the result of a limited subject position offered by lesbian feminism.