Yeats's Book of 'Numberless Dreams': His Notebooks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

90 Av 100 Ålänningar Sågar Upphöjd Korsning Säger Nej

Steker crépe på Lilla holmen NYHETER. Fransmannen Zed Ziani har fl yttat sitt créperie till Lilla holmen i Mariehamn och för första gången på många år fi nns det servering igen på friluftsområdet. Både salta och söta crépe, baguetter och kaffe fi nns på menyn i det lilla caféet med utsikt över fågeldammen Lördag€ SIDAN 18 12 MAJ 2007 NR 100 PRIS 1,20 och Slemmern. 90 av 100 ålänningar sågar upphöjd korsning Säger nej. Annette Gammals deltog i Nyans gatupejling om Ålandsvägens upphöjda korsning- ar. Men planerarna har politikernas uppdrag att se Men frågan är: Vems bekvämlighet är viktigast? till också den lätta trafi kens intressen. NYHETER. Ska alla trafi kanter – bilister, – Jag tycker mig känna igen trafi kplane- ålänningarna kanske har svårare än andra att – Jag hatar bumpers, sa Ingmar Håkansson cyklister, fotgängare och gamla med rullator ringsdiskussionen från 1960-talet när devisen ge avkall på bilbekvämligheten. från Lumparland som har jobbat 26 år som – behandlas jämlikt i stadstrafi ken? var att bilarna ska fram, allt ska ske på bilis- – Åland är väldigt bilberoende. Men man yrkeschaufför. Ja, säger planerarna i Mariehamn. Politi- ternas villkor och de oskyddade och sårbara måste ändå tänka på att också andra har rätt 90 personer svarade nej på frågan om de vill kerna har godkänt de styrdokument som de trafi kanterna får klara sig bäst de kan, säger till en säker trafi kmiljö. ha upphöjda korsningar, tio svarade ja. baserar ombyggnaden av Ålandsvägen på. tekniska nämndens ordförande Folke Sjö- Känslorna var starka då Nyan i går pejlade – Jag har barn som skall gå över Ålandsvä- Det som nu har hänt är att en del politiker lund. -

W. B. Yeats Easter 1916 This Poem Deals with the Dublin Rebellion Of

W. B. Yeats Easter 1916 This poem deals with the Dublin Rebellion of Easter 1916 which is believed to have been the beginning of modern Ireland, in spite of its immediate failure. Yeats was in Dublin when it happened, and though at first he was against the violence and the bloodshed that accompanied it and he thought the sacrifice of its leaders wasteful, he sympathized with the rebels when sixteen of them were executed. In Stanza One the poet describes the previous lives of the rebels to suggest that they were average or normal citizens who sacrificed their lives for the sake of Irish independence. They were normal Irish people with "vivid faces" and he used to meet them with a nod of the head or saying polite meaningless words. However, he shared with them the love of Ireland: Be certain that they and I But lived where motely is worn The word "motely" means colourful dress which symbolizes Irish people. The stanza ends with "a terrible beauty is born" which may allude to the Birth of Hellen of Troy, Maud Gonne and Ireland because Irish independence will be accompanied by violence and bloodshed. In Stanza Two the poet mentions some of the significant rebels b eginning with "that woman" which refers to Maud Gonne, the most beautiful woman in Ireland according to Ye ats who was with the rebels; she was imprisoned in England after the rising but she escaped to Dublin in 1918. Because of her interest in Irish independence and in politics and argument, her beautiful voice became shrill. -

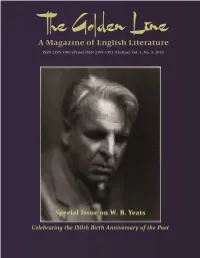

Online Version Available at Special Issue on WB Yeats Volume 1, Number 3, 2015

The Golden Line A Magazine of English Literature Online version available at www.goldenline.bcdedu.net Special Issue on W. B. Yeats Volume 1, Number 3, 2015 Guest-edited by Dr. Zinia Mitra Nakshalbari College, Darjeeling Published by The Department of English Bhatter College, Dantan P.O. Dantan, Dist. Paschim Medinipur West Bengal, India. PIN 721426 Phone: 03229-253238, Fax: 03229-253905 Website: www.bhattercollege.ac.in Email: [email protected] The Golden Line: A Magazine on English Literature Online version available at www.goldenline.bcdedu.net ISSN 2395-1583 (Print) ISSN 2395-1591 (Online) Inaugural Issue Volume 1, Number 1, 2015 Published by The Department of English Bhatter College, Dantan P.O. Dantan, Dist. Paschim Medinipur West Bengal, India. PIN 721426 Phone: 03229-253238, Fax: 03229-253905 Website: www.bhattercollege.ac.in Email: [email protected] © Bhatter College, Dantan Patron Sri Bikram Chandra Pradhan Hon’ble President of the Governing Body, Bhatter College Chief Advisor Pabitra Kumar Mishra Principal, Bhatter College Advisory Board Amitabh Vikram Dwivedi Assistant Professor, Shri Mata Vaishno Devi University, Jammu & Kashmir, India. Indranil Acharya Associate Professor, Vidyasagar University, West Bengal, India. Krishna KBS Assistant Professor in English, Central University of Himachal Pradesh, Dharamshala. Subhajit Sen Gupta Associate Professor, Department of English, Burdwan University. Editor Tarun Tapas Mukherjee Assistant Professor, Department of English, Bhatter College. Editorial Board Santideb Das Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College Payel Chakraborty Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College Mir Mahammad Ali Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College Thakurdas Jana Guest Lecturer, Bhatter College ITI, Bhatter College External Board of Editors Asis De Assistant Professor, Mahishadal Raj College, Vidyasagar University. -

Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats

Colby Quarterly Volume 22 Issue 4 December Article 3 December 1986 Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats Donald Pearce Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 22, no.4, December 1986, p.198-204 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Pearce: Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats by DONALD PEARCE He made songs because he had a will to make songs and not because love moved him thereto. Ue de Saint-eire VERY POET is, at bottom, a kind of alchemist, every poem an ap E paratus for transn1uting the "base metal" of life into the gold of art. Especially is this true of Yeats, not only as regards the ambient world of other people and events, but also the private one of his own art and thought: "Myself must I remake / Till I am Timon and Lear / Or that William Blake...." So persistent was he in this work of transmutation, and so adept at it, that the ordinary affairs of daily life often must have seemed to him little more than a clumsy version of a truer, more intense life lived in the clarified world of his imagination. However that may have been for Yeats, it is certainly true for his readers: incidents, persons, squabbles with which or whom he was intermittently entangled increas ingly owe what importance they still have for us to the fact of occurring somewhere, caught and finalized, in the passionate world of his poems. -

Austin Clarke Papers

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 83 Austin Clarke Papers (MSS 38,651-38,708) (Accession no. 5615) Correspondence, drafts of poetry, plays and prose, broadcast scripts, notebooks, press cuttings and miscellanea related to Austin Clarke and Joseph Campbell Compiled by Dr Mary Shine Thompson 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 7 Abbreviations 7 The Papers 7 Austin Clarke 8 I Correspendence 11 I.i Letters to Clarke 12 I.i.1 Names beginning with “A” 12 I.i.1.A General 12 I.i.1.B Abbey Theatre 13 I.i.1.C AE (George Russell) 13 I.i.1.D Andrew Melrose, Publishers 13 I.i.1.E American Irish Foundation 13 I.i.1.F Arena (Periodical) 13 I.i.1.G Ariel (Periodical) 13 I.i.1.H Arts Council of Ireland 14 I.i.2 Names beginning with “B” 14 I.i.2.A General 14 I.i.2.B John Betjeman 15 I.i.2.C Gordon Bottomley 16 I.i.2.D British Broadcasting Corporation 17 I.i.2.E British Council 17 I.i.2.F Hubert and Peggy Butler 17 I.i.3 Names beginning with “C” 17 I.i.3.A General 17 I.i.3.B Cahill and Company 20 I.i.3.C Joseph Campbell 20 I.i.3.D David H. Charles, solicitor 20 I.i.3.E Richard Church 20 I.i.3.F Padraic Colum 21 I.i.3.G Maurice Craig 21 I.i.3.H Curtis Brown, publisher 21 I.i.4 Names beginning with “D” 21 I.i.4.A General 21 I.i.4.B Leslie Daiken 23 I.i.4.C Aodh De Blacam 24 I.i.4.D Decca Record Company 24 I.i.4.E Alan Denson 24 I.i.4.F Dolmen Press 24 I.i.5 Names beginning with “E” 25 I.i.6 Names beginning with “F” 26 I.i.6.A General 26 I.i.6.B Padraic Fallon 28 2 I.i.6.C Robert Farren 28 I.i.6.D Frank Hollings Rare Books 29 I.i.7 Names beginning with “G” 29 I.i.7.A General 29 I.i.7.B George Allen and Unwin 31 I.i.7.C Monk Gibbon 32 I.i.8 Names beginning with “H” 32 I.i.8.A General 32 I.i.8.B Seamus Heaney 35 I.i.8.C John Hewitt 35 I.i.8.D F.R. -

Literary Pairs in Comparative Readings Across National and Cultural Divides

Literary Pairs in Comparative Readings across National and Cultural Divides Literary Pairs in Comparative Readings across National and Cultural Divides By Yarmila Nikolova Daskalova Literary Pairs in Comparative Readings across National and Cultural Divides By Yarmila Nikolova Daskalova This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Yarmila Nikolova Daskalova All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-1380-7 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-1380-8 For Sarkis and Lucia CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Wandering With(out) a Muse: Intertextuality and Romantic Disguise .... 9 New Dimensions in Conceptualizing Beauty and the Principle of Originality in the Works of Edgar Allan Poe and Charles Baudelaire ...... 24 “A Word that Breathes Distinctly has Not the Power to Die”: The Life of Words in the Poetry of Emily Dickinson and Marina Tsvetaeva ................................................................................ 48 Charles Baudelaire’s “The Voyage” and W. B. Yeats’s “News for the Delphic Oracle”: Politics of Perception and Strategies of Representation in Two Poems on Departure and (Withheld) Arrival ........ 98 Haunting Romanticisms: Day-dreaming and Obsessive Imagery in the Works of Edgar Allan Poe and Peyo Yavorov .............................. 115 W. B Yeats And P. K. Yavorov: Concepts of National Mythopoetics .... 142 W.B. -

Untitled.Pdf

STRUCTURE IN THE COLLECTED POEMS OF W. B. YEATS A Thesis Presented to the School of Graduate Studies Drake University In Partial Fulfil£ment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English by Barbara L. Croft August 1970 l- ----'- _ u /970 (~ ~ 7cS"' STRUCTURE IN THE COLLECTED POEMS OF w. B. YEATS by Barbara L. Croft Approved by CGJmmittee: J4 .2fn., k ~~1""-'--- 7~~~ tI It t ,'" '-! -~ " -i L <_ j t , }\\ ) '~'l.p---------"'----------"? - TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. INTRODUCTION ••••• . 1 2. COMPLETE OBJECTIVITY . • • . 23 3. THE DISCOVERY OF STRENGTH •••••••• 41 4. C~1PLETE SUBJECTIVITY •• • • • ••• 55 5. THE BREAKING OF STRENGTH ••••••••• 79 BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 90 i1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION There is, needless to say, an abundance of criticism on W. B. Yeats. Obsessed with the peet's occultism, critics have pursued it to a depth which Yeats, a notedly poor scholar, could never have equalled; nor could he have matched their zeal for his politics. While it is not the purpose here to evaluate or even extensively to examine this criticism, two critics in particular, Richard Ellmann and John Unterecker, will preve especially valuable in this discussion. Ellmann's Yeats: ----The Man and The Masks is essentially a critical biography, Unterecker's ! Reader's Guide l! William Butler Yeats, while it uses biographical material, attempts to fecus upon critical interpretations of particular poems and groups of poems from the Collected Poems. In combination, the work of Ellmann and Unterecker synthesize the poet and his poetry and support the thesis here that the pattern which Yeats saw emerging in his life and which he incorporated in his work is, structurally, the same pattern of a death and rebirth cycle which he explicated in his philosophical book, A Vision. -

Hermetic Philosophy and Dual Selfhood in Yeats's

“An Image of Mysterious Wisdom”: Hermetic Philosophy and Dual Selfhood in Yeats’s Poetic Dialogues Treball de Fi de Grau/ BA dissertation Author: Paula Moschini Izquierdo Supervisor: Jordi Coral Escolà Departament de Filologia Anglesa i de Germanística Grau d’Estudis Anglesos June 2018 CONTENTS 0. Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 0.1. Methodology and Analysed Concepts ................................................................................... 1 0.2. Yeats and Philosophy: The Self and the Antinomies ......................................................... 2 0.3. The Hermetic Dialogue ............................................................................................................. 7 0.4. The Aesthetics of Artistic Reinterpretation: The Symbol ................................................ 9 1. Ego Dominus Tuus ....................................................................................................... 10 1.1. The Tower as a Symbol for the Self and “the Image” ..................................................... 11 1.2. Unity of Being in Artists ......................................................................................................... 14 1.3. A Poem about the Necessity of the Intuitive Wisdom in Poetry ................................... 16 2. A Dialogue of Self and Soul ........................................................................................ 18 2.1. Love and War: The Eternal -

L'italia E L'eurovision Song Contest Un Rinnovato

La musica unisce l'Europa… e non solo C'è chi la definisce "La Champions League" della musica e in fondo non sbaglia. L'Eurovision è una grande festa, ma soprattutto è un concorso in cui i Paesi d'Europa si sfidano a colpi di note. Tecnicamente, è un concorso fra televisioni, visto che ad organizzarlo è l'EBU (European Broadcasting Union), l'ente che riunisce le tv pubbliche d'Europa e del bacino del Mediterraneo. Noi italiani l'abbiamo a lungo chiamato Eurofestival, i francesi sciovinisti lo chiamano Concours Eurovision de la Chanson, l'abbreviazione per tutti è Eurovision. Oggi più che mai una rassegna globale, che vede protagonisti nel 2016 43 paesi: 42 aderenti all'ente organizzatore più l'Australia, che dell'EBU è solo membro associato, essendo fuori dall'area (l’anno scorso fu invitata dall’EBU per festeggiare i 60 anni del concorso per via dei grandi ascolti che la rassegna fa in quel paese e che quest’anno è stata nuovamente invitata dall’organizzazione). L'ideatore della rassegna fu un italiano: Sergio Pugliese, nel 1956 direttore della RAI, che ispirandosi a Sanremo volle creare una rassegna musicale europea. La propose a Marcel Bezençon, il franco-svizzero allora direttore generale del neonato consorzio eurovisione, che mise il sigillo sull'idea: ecco così nascere un concorso di musica con lo scopo nobile di promuovere la collaborazione e l'amicizia tra i popoli europei, la ricostituzione di un continente dilaniato dalla guerra attraverso lo spettacolo e la tv. E oltre a questo, molto più prosaicamente, anche sperimentare una diretta in simultanea in più Paesi e promuovere il mezzo televisivo nel vecchio continente. -

1 Yeats Considered As the Archetypal Fool: a Tantric Reading of the Herne’S Egg Margot Wilson Mphil(R)

Yeats Considered as the Archetypal Fool: A Tantric Reading of The Herne’s Egg Margot Wilson MPhil(R) Yeats Considered as the Archetypal Fool: A Tantric Reading of ‘The Herne’s Egg (1938)’ Margot Wilson Background This essay considers Yeats’s The Herne’s Egg (1938) as the journey of the archetypal Fool1 of Tarot from Indian Vedic and Tantric perspectives. In brief, the Tarot2 system begins with ‘0 = The Fool’ and ends with ‘21 = The World’. These twenty-one cards are known as the ‘Major Arcana’ and are used in combination with four suites of ‘Minor Arcana’ cards that correspond with the hearts, clubs, diamonds and spades of recreational playing cards. In Tarot, these suites become cups, pentacles, swords and wands, symbolising water, earth, air and fire. The twenty-one Major Arcana (twenty- two including zero) comprise three cycles of seven, the number seven corresponding with the seven inner planets ‘Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn’; the Sun is synonymous with the bearing of life and Saturn synonymous with the approach of death. These planets also relate to the Vedic system of chakras, of which there are seven. Each card represents a stage of the cycle of life; note the repetition of 0 = zero and the ‘0’ of laurel in The World card. This represents the mathematical expression of zero and the symbolic image of the Ouroboros. The first card, The Fool (0) progresses to the Judgement card (XX), after which the final stage, The World is obtained, or not. If Judgement falls against the Fool, he returns to zero. -

The George Russell Collection at Colby College

Colby Quarterly Volume 4 Issue 2 May Article 6 May 1955 The George Russell Collection at Colby College Carlin T. Kindilien Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, series 4, no.2, May 1955, p.31-55 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Kindilien: The George Russell Collection at Colby College Colby Library Quarterly 3 1 acted like a lot of bad boys in their conversation with each other but they did it in beautiful English. I never knew AE to tell a story which was in the slightest degree off color or irreverent. And yet, of an evening, he could grip your closest attention as you listened steadily to an endless flow of words from nine in the evening till two in the morn ing. In 1934 Mary Rumsey offered to pay AE's expenses to come to this country to consult with the Department of Agriculture. Robert Frost was somewhat annoyed because he felt we should have called him in rather than AE. At the moment, however, AE, when talking to our Exten sion people, furnished a type of profound inspiration which I thought was exceedingly important. He worked largely out of the office of M. L. Wilson, who later became Under-Secretary of Agriculture and Director of Extension. In this period I had him out to our apartment with Justice Stone, the Morgenthaus, and others. -

The Influence of Hindu, Buddhist, and Musldi Thought on Yeats' S Poetry

THE INFLUENCE OF HINDU, BUDDHIST, AND MUSLDI THOUGHT ON YEATS' S POETRY by SHAMSUL ISLAM • ~ INFLUENCE Q! HINDU, BUDDHIST, AND MUSLIM THOUGHT Q!i YEATS'S POETRY A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Shamsul Islam, B.A..B!ms., M.A. (Panjab) Department of English, Facul ty of Gradua te Studies and Research, lcGill University. August 1966. fn'1 \:::,./ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my thank:s to Dr. Alan Heuser, Department of English, JlcÇill University, for his constant advice and encouragement. I would a.lso like to tha.nk Dr. Joyce Hemlow, Department of English, HcGill University, for her constant guidance and help. I am a.lso tha.nkful to Kra. Blincov, Depa.rtment of English, McGill University, for her wa.rmth and affection. I am a.lso gratef'ul to the Cana.dian Commonwealth Scb.ola.rship Commi ttee for the awa.rd of a. Commonwea.l th Bcholarship, which ena.bled me to complete my woà at McGill. OONTENTS Introduction 1 Chapter I. The Maze of Eastern Thought - Early Impact 1886-1889, with some remarks on Yeats's interest in the Orient 1890- 1911 3 Chapter II. New Light from the East: Tagore 1912- 1919, wi th remarks on some poems 1920- 1924 20 Chapter III. The Wor1d of Philoaophy -- Yeatsian Synthesis 1925-1939 31 Conclusion 47 Bibliography 50 1 Introduction Yeats vss part of a late nineteentb-centur,y European literar,y mo:Rement vhiah~ dissatisfied rlth Western tradition, both scientific and religious, looked tovards the Orient for enlightemnent.