IOC-UNODC Reporting Mechanisms in Sport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bi-Weekly Bulletin 5-18 March 2019

INTEGRITY IN SPORT Bi-weekly Bulletin 5-18 March 2019 Photos International Olympic Committee INTERPOL is not responsible for the content of these articles. The opinions expressed in these articles are those of the authors and do not represent the views of INTERPOL or its employees. INTERPOL Integrity in Sport Bi-Weekly Bulletin 5-18 March 2019 SENTENCES/SANCTIONS Chile Mauricio Alvarez-Guzman banned for life for tennis match-fixing and associated corruption offences Chilean tennis player Mauricio Alvarez-Guzman has been handed a lifetime ban from professional tennis after being found guilty of match-fixing and associated corruption offences, which breach the sport’s Tennis Anti-Corruption Program (TACP). The 31-year old was found to have attempted to contrive the outcome of an August 2016 ATP Challenger match in Meerbusch, Germany by offering a player €1,000 to lose a set. In addition he was found guilty of contriving the singles draw of the ITF F27 Futures tournament played in July 2016 in Antalya, Turkey by purchasing a wild card for entry into the singles competition. An intention to purchase a wild card for the doubles competition of the same tournament did not come to fruition, but still stands as a corruption offence. The disciplinary case against Mr Alvarez-Guzman was considered by independent Anti-Corruption Hearing Officer Charles Hollander QC at a Hearing held in London on 11 March 2019. Having found him guilty of all charges, the lifetime ban imposed by Mr Hollander means that with effect from 14 March 2019 the player is permanently excluded from competing in or attending any tournament or event organised or sanctioned by the governing bodies of the sport. -

Anti-Doping Rules

Book D – D3.1 ANTI-DOPING RULES (In force from 1 April 2020) Book D – D3.1 Book D – D3.1 Specific Definitions The words and phrases used in these Rules that are defined terms (denoted by initial capital letters) shall have the meanings specified in the Constitution and the Generally Applicable Definitions, or (in respect of the following words and phrases) the following meanings: "Athletics Integrity Unit" means the unit described in Part X of the Constitution and “Integrity Unit” has the same meaning. "ADAMS" The Anti-Doping Administration and Management System is a web-based database management tool for data entry, storage, sharing and reporting designed to assist Stakeholders and WADA in their anti-doping operations in conjunction with data protection legislation. "Administration" Providing, supplying, supervising, facilitating or otherwise participating in the Use or Attempted Use by another Person of a Prohibited Substance or Prohibited Method. However, this definition shall not include the actions of bona fide medical personnel involving a Prohibited Substance or Prohibited Method used for genuine and legal therapeutic purposes or other acceptable justification and shall not include actions involving Prohibited Substances which are not prohibited in Out-of-Competition Testing unless the circumstances as a whole demonstrate that such Prohibited Substances are not intended for genuine and legal therapeutic purposes or are intended to enhance sport performance. "Adverse Analytical Finding" A report from a WADA-accredited laboratory or other WADA- approved laboratory that, consistent with the International Standard for Laboratories and related Technical Documents, identifies in a Sample the presence of a Prohibited Substance or its Metabolites or Markers (including elevated quantities of endogenous substances) or evidence of the Use of a Prohibited Method. -

Procedural Rules

SR/Adhocsport/57/2019 IN THE MATTER OF PROCEEDINGS BROUGHT UNDER THE ANTI-DOPING RULES OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF ATHLETICS FEDERATIONS Before: Michael Beloff QC (Chair) Francisco A. Larios Jeffrey Benz BETWEEN: International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) Anti-Doping Organisation -and- Jarrion Lawson Respondent DECISION OF THE DISCIPLINARY TRIBUNAL A. INTRODUCTION 1. The Claimant, the International Association of Athletics Federations (“IAAF”), is the International Federation governing the sport of Athletics worldwide.1 It has its registered seat in Monaco. 2. The Respondent, Mr. Jarrion Lawson (the “Athlete”), is a 25-year-old American long jumper/sprinter. 3. On February 27, 2019, the Athletics Integrity Unit (“AIU”) charged the Athlete pursuant to Articles 2.1 and 2.2 of the IAAF Anti-Doping Rules (“ADR”) with an Anti-Doping Rule Violation (“ADRV’’) for the Presence and Use of a Prohibited Substance or its Metabolites or Markers, Epitrenbolone (a metabolite of Trenbolone). A. FACTUAL BACKGROUND 4. Below is a chronological summary of the undisputed evidence before the Disciplinary Tribunal (the “Tribunal”). 5. On April 11, 2018, the Athlete tested negative at a doping control test. 6. At all times between April 11, 2018 and June 2, 2018 he was subject to testing, during which period he competed on May 20, 2018 in the Seiko Golden Grand Prix Osaka 2018 in Osaka, Japan. 7. On June 2, 2018 in Springdale, Arkansas (USA), the Athlete underwent an Out-of- Competition doping control test following the Osaka meet. The Athlete provided a urine Sample with reference number 1609851 (the “Sample”). 8. On June 14, 2018, the A Sample was analysed by the WADA-accredited laboratory in Los Angeles, California (USA) (the “Laboratory”) and revealed the presence of Epitrenbolone (the “Adverse Analytical Finding” or “AAF”). -

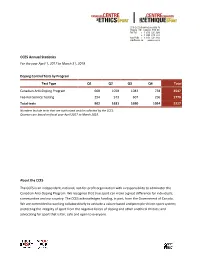

2017-2018 Doping Control Statistics

CCES Annual Statistics For the year April 1, 2017 to March 31, 2018 Doping Control Tests by Program Test Type Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Total Canadian Anti-Doping Program 668 1058 1083 738 3547 Fee-For-Service Testing 294 573 607 296 1770 Total tests 962 1631 1690 1034 5317 Numbers include tests that are authorized and/or collected by the CCES. Quarters are based on fiscal year April 2017 to March 2018. About the CCES The CCES is an independent, national, not-for-profit organization with a responsibility to administer the Canadian Anti-Doping Program. We recognize that true sport can make a great difference for individuals, communities and our country. The CCES acknowledges funding, in part, from the Government of Canada. We are committed to working collaboratively to activate a values-based and principle-driven sport system; protecting the integrity of sport from the negative forces of doping and other unethical threats; and advocating for sport that is fair, safe and open to everyone. Anti-Doping Rule Violations The following violations and sanctions were reported between April 1, 2017 and March 31, 2018. Athlete Sex Sport Violation Sanction Anderson- 2 months ineligibility M Athletics Presence: cannabis Richards, Tacuma Ends September 7, 2017 Arnaout, Presence: GW501516 and SARM S- 4 years ineligibility M Powerlifting Mohamad 22 Ends February 17, 2021 U SPORTS 1 year ineligibility Boucher, Bettina M Presence: ephedrine Track & Field Ends February 3, 2019 2 years ineligibility Chen, Ivan M Powerlifting Presence: D-amphetamine Ends October 15, 2019 -

First Consultation: Questions to Discuss and Consider

WADAConnect Page 1 of 263 2021 Code Review - First Consultation: Questions to Discuss and Consider Showing: All (637 Comments) Article 2 - Fraudulent Conduct (29) ITTF SUBMITTED Françoise Dagouret, Anti-Doping Manager (Switzerland) Sport - IF – Summer Olympic Indeed this could be addressed in ADRV Art. 2.5 subject to deletion of "with any part of Doping Control" in the title.The above suggestion could be added as follows:".... providing fraudulent information or documents to an Anti-Doping Organization or during an investigation or a results management process, or intimidating, etc......." World Rugby SUBMITTED David Ho, Anti-Doping Manager - Compliance and Results (Ireland) Sport - IF – Summer Olympic We consider that some amendments are needed to this clause in order to assist with cases where a player or representative may attempt to intentionally mislead a panel. For example lying under oath would be fraudulent conduct. Is there a way to put the onus on the athlete to make sure that the case is not fabricated? We understand this may already fall under tampering however we have proposed the following wording: 2.5 Tampering or Attempted Tampering with any part of Doping Control Conduct which subverts any part of the Doping Control process but which would not otherwise be included in the definition of Prohibited Methods. Tampering shall include, without limitation, intentionally interfering or attempting to interfere with a Doping Control official, providing fraudulent, misleading and/or deceptive information, statements and/or documentation and/or calling an expert or witness who provides fraudulent, misleading and/or deceptive information, statements and/or documentation to an Anti-Doping Organization and/or hearing body and/or intimidating or attempting to intimidate a potential witness. -

Decision of the Athletics Integrity Unit in the Case of Ms Andressa De Morais

DECISION OF THE ATHLETICS INTEGRITY UNIT IN THE CASE OF MS ANDRESSA DE MORAIS Introduction 1. In April 2017, World Athletics1 established the Athletics Integrity Unit ("AIU") whose role is to protect the integrity of the sport of Athletics, including fulfilling World Athletics' obligations as a Signatory to the World Anti-Doping Code. World Athletics has delegated implementation of its Anti-Doping Rules ("ADR") to the AIU, including but not limited to the following activities in relation to International- Level Athletes: Testing, Investigations, Results Management, Hearings, Sanctions and Appeals. 2. Ms. Andressa De Morais is a 29-year old Brazilian discus thrower who is an International-Level Athlete for the purposes of the ADR (the “Athlete"). 3. This decision is issued pursuant to Article 8.4.7 ADR which provides that: 8.4.7 "[i]n the event that […] the Athlete or Athlete Support Person admits the Anti-Doping Rule Violation(s) charged and accedes to the Consequences specified by the Integrity Unit, a hearing before the Disciplinary Tribunal shall not be required. In such a case, the Integrity Unit…shall promptly issue a decision confirming...the commission of the Anti-Doping Rule Violation(s) and the imposition of the Specified Consequences (including, if applicable, a justification for why the maximum potential sanction was not imposed)". The Athlete's commission of an Anti-Doping Rule Violation 4. On 6 August 2019, the Athlete provided a urine Sample In-Competition at the ‘XVIII Pan American Games’ in Lima, Peru (the “Games”), which was given code 6380337 (the “Sample”). 5. On 11 August 2019, the World Anti-Doping Agency (“WADA”) accredited laboratory in Montreal, Canada (the “Laboratory”), reported an Adverse Analytical Finding (the “AAF”) for the presence of a SARM2 S-223 (“S-22”) in the Sample. -

2017 USATF Athlete Representative Exam Study Booklet

2017 ATHLETE REPRESENTATIVE EXAM MATERIALS 19046_2017_Athlete_Rep_Exam_Materials_Cover_8_5x11_Final.indd 1 8/4/17 10:15 AM TABLE OF CONTENTS Topic Booklet Divider ATHLETE – AGENT RELATIONSHIP……………………………………….………………………………………….……...1 USATF & IAAF OVERVIEW………………………………………………….………………………………………….……....2 2017 USATF Governing Regulation 25………………………….…………………………………….……...……2A ELITE ATHLETE SUPPORT PROGRAMS……………………………….…………………………………….……....……...3 COMPETITION PARTICIPATION AND COMPENSATION…………….…………………………………….……......…….4 ANTI-DOPING……………………………………………………………….……………………………………...…......……...5 2017 USATF Governing Regulation 20……………………….……………………………………………...…….5A IAAF Anti-Doping Rules .……………………………………….……………………………………………...…….5B USADA Whereabouts Policy………………………………….……………………………………………….…….5C Protocol for Olympic and Paralympic Movement Testing...……………………………………………….……..5D USADA Pocket Guide………….............……………………………………………….………….………….…….5E USADA Policy for Therapeutic Use Exemptions ………………………………….…………………….….…….5F IAAF Therapeutic Use Exemptions…………………………………………………………………………...…….5G 2018 WADA Prohibited List…………………………………………………………………………………....…….5H COMMUNICATION AND PUBLIC OUTREACH……………………………………………………………….……….……...6 ATHLETE – AGENT RELATIONSHIP 1 I. ATHLETE/AGENT RELATIONSHIP (general) A. What is the relationship between athlete and agent? 1. It is contractual. 2. The athlete is hiring the agent to work for him or her. a. It is important to remember that at all times, the agent works for the athlete. 3. It is fiduciary a. Agent has duty to discover and disclose -

Adrvs) Report

World Anti-Doping Program 2018 Anti-Doping Rule Violations (ADRVs) Report This Report is compiled based on decisions received by WADA before 2 March 2020. Table of Contents Page Terms and Abbreviations……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Explanations and Definitions…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………4 Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………6 Section 1: Outcomes of 2018 AAFs 1 by Sport Category…………………………………………………………………9 Table 1 - AAF Outcomes by Sport Category………………………………………………………………………………………………10 Table 2 - AAF Outcomes by Sport Category - ASOIF Sports/Disciplines…………………………………………………10 Table 3 - AAF Outcomes by Sport Category - AIOWF Sports/Disciplines………………………………………………12 Table 4 - AAF Outcomes by Sport Category - ARISF Sports/Disciplines………………………………………………12 Table 5 - AAF Outcomes by Sport Category - AIMS Sports/Disciplines…………………………………………………14 Table 6 - AAF Outcomes by Sport Category - IPC Sports/Disciplines……………………………………………………14 Table 7 - AAF Outcomes by Sport Category - Sports/Disciplines for Athletes with an Impairment……15 Table 8 - AAF Outcomes by Sport Category - Other Sports - Code Signatories……………………………………16 Table 9 - AAF Outcomes by Sport Category - Other Sports……………………………………………………………………16 Section 2: Outcomes of 2018 AAFs1 by Testing Authority Category…………………………………………18 Table 1 - AAF Outcomes by TA Category…………………………………………………………………………………………………19 Table 2 - AAF Outcomes by TA Category - ASOIF IFs……………………………………………………………………………20 -

ASOIF International Federation Governance Project Examples of Good Governance Practice

ASOIF International Federation Governance Project Examples of Good Governance Practice Updated 2 September 2019 Introduction This document lists a number of examples of good governance practice among the International Federations (IFs) which are Full Members of the Association of Summer Olympic International Federations (ASOIF). The examples have been identified following the First and Second Reviews of IF Governance conducted by the ASOIF Governance Taskforce in 2016- 17 and between November 2017 and March 2018. About the good practice examples The examples below all relate directly to one of the 50 questions in the 2017-18 edition of the questionnaire and are numbered accordingly. In most cases, there are two or three examples. In order to be included, the IF usually demonstrated that it fulfilled the criteria of the specific question in a “state of the art” way. An objective in compiling the list was to provide examples from a wide variety of IFs. The selected examples should therefore not be regarded as definitively the best in each category, nor should the omission of a particular IF example be understood as any kind of criticism – for many of the questions there were too many good examples to include them all. In other cases only one IF is cited, either because it provided the clearest good example, or because the criteria for the indicator in the questionnaire proved very difficult for IFs to fulfil. Most of the examples have been checked with the IFs in question. As governance is an evolving process, it is likely that some of the web pages and documents referred to will be updated or replaced fairly soon. -

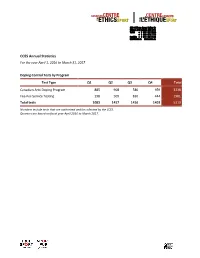

2016-2017 Doping Control Statistics

CCES Annual Statistics For the year April 1, 2016 to March 31, 2017 Doping Control Tests by Program Test Type Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Total Canadian Anti-Doping Program 885 908 586 959 3338 Fee-For-Service Testing 198 509 830 444 1981 Total tests 1083 1417 1416 1403 5319 Numbers include tests that are authorized and/or collected by the CCES. Quarters are based on fiscal year April 2016 to March 2017. Anti-Doping Rule Violations The following violations and sanctions were reported between April 1, 2016 and March 31, 2017. Athlete Sex Sport Violation Sanction Barber, Shawnacy M Athletics Presence: cocaine No fault or negligence Whereabouts 4 years ineligibility Connor, Earle M Para-athletics Admission Ends June 4, 2020 Presence: nandrolone 2 months ineligibility Elcock, Darren M Judo Presence: cannabis Ends March 8, 2017 3 years, 10 months U SPORTS Fortin, Jonathan M Presence: methandienone ineligibility Football Ends February 14, 2020 U SPORTS Presence: dehydrochlor- 4 years ineligibility Grosman, Tristan M Football methyltestosterone Ends April 25, 2020 U SPORTS 18 months ineligibility Maheu, Justin M Presence: ephedrine Soccer Ends April 24, 2017 U SPORTS Presence: SARM S-22, ibutamoren, 4 years ineligibility McDonald, Moy M Football clenbuterol Ends March 23, 2020 U SPORTS 2 years ineligibility McNicoll, Daniel M Presence: D- and L-Amphetamine Football Ends November 9, 2018 Ramsay-Marshall, U SPORTS 2 months ineligibility M Presence: cannabis Joren Soccer Ends November 26, 2016 Tagziev, 4 years ineligibility M Wrestling Presence: meldonium Tamerlan Ends August 9, 2020 CCAA 2 months ineligibility Terbasket, Nicola F Presence: cannabis Basketball Ends June 11, 2016 Tremblay, U SPORTS M Presence: salbutamol Reprimand Charles-William Football Woodhouse, F Alpine skiing Presence: methylphenidate Reprimand Emma To view the full Canadian Anti-Doping Sanction Registry, visit www.cces.ca/results. -

SR/Adhocsport/64/2018

SR/Adhocsport/64/2018 IN THE MATTER OF PROCEEDINGS BROUGHT UNDER THE ANTI-DOPING RULES OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF ATHLETICS FEDERATIONS. Before: Michael Beloff QC (Chair) Maidie Oliveau Patrick Grandjean BETWEEN: INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF ATHLETICS FEDERATIONS (“IAAF”) Anti-Doping Organisation - and - ASBEL KIPROP Respondent Decision of the Disciplinary Tribunal - 1 - A. INTRODUCTION 1. Mr Asbel Kiprop, a Kenyan athlete (“the Athlete”) is an Olympic gold medallist in the 1500 metres (Beijing 2008) and a triple world champion in the same event, Daegu (2011), Moscow (2013) and Beijing (2015). He holds the third fastest time ever over that distance. 2. The Athlete has been charged by the Athletics Integrity Unit (“AIU”) acting on behalf of the IAAF1, with violations of the IAAF Anti-Doping Rules (“ADR”) as described below. B. CHRONOLOGY 3. On 27 November 2017, the Athlete underwent an Out-of-Competition doping control in Iten, Kenya and provided a urine sample numbered 3099705 (“the Sample”). 4. Between 5 and 22 December 2017, the Sample was analysed by the WADA accredited laboratory in Stockholm, Sweden (the “Laboratory”) and revealed the presence of “S2. Peptide Hormones, Growth Factors, Related Substances and Mimetics/erythropoietin (EPO)” (“EPO”) (the “Adverse Analytical Finding”). 5. EPO is included in section 2 of the WADA 2017 Prohibited List, Peptide Hormones Growth Factors, Related Substances, and Mimetics2. It is a prohibited non- specified substance, which accordingly an athlete may take neither in nor Out- of-Competition. It is administered by injection and artificially increases red blood cells so enhancing stamina and assisting recovery. 1 The international federation governing the sport of Athletics worldwide. -

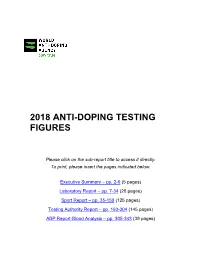

2018 Anti-Doping Testing Figures Report

2018 ANTI-DOPING TESTING FIGURES Please click on the sub-report title to access it directly. To print, please insert the pages indicated below. Executive Summary – pp. 2-6 (5 pages) Laboratory Report – pp. 7-34 (28 pages) Sport Report – pp. 35-159 (125 pages) Testing Authority Report – pp. 160-304 (145 pages) ABP Report-Blood Analysis – pp. 305-343 (39 pages) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Executive Summary is intended to assist stakeholders in navigating the data outlined within the 2018 Testing Figures Report (2018 Report) and to highlight overall trends. The 2018 Report summarizes the results of all the samples WADA-accredited Laboratories analyzed and reported into WADA’s Anti-Doping Administration and Management System (ADAMS) in 2018. This is the fourth set of global testing results since the 2015 World Anti-Doping Code (Code) came into effect. The 2018 Report – which includes this Executive Summary and sub-reports by Laboratory, Sport, Testing Authority (TA) and Athlete Biological Passport (ABP) Blood Analysis – includes in- and out-of- competition urine samples; blood and ABP blood data; and, the resulting Adverse Analytical Findings (AAFs) and Atypical Findings (ATFs). REPORT HIGHLIGHTS • A 6.9% increase in the overall number of samples analyzed: 322,050 in 2017 to 344,177 in 2018. • A slight decrease in the total percentage of AAFs: 1.43% in 2017 (4,596 AAFs from 322,050 samples) to 1.42% in 2018 (4,896 AAFs from 344,177 samples). • About 60% of WADA-accredited Laboratories saw an increase in the total number of samples recorded. • An increase in the total number and percentage of non-ABP blood samples analyzed: 8.62% in 2017 (27,759 of 322,050) to 9.11% in 2018 (31,351 of 344,177).