SR/Adhocsport/64/2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chronic Adaptations to High Altitude in Elite East African Runners

What we can learn from the world’s best endurance athletes with particular focus on training and competition Yannis Pitsiladis, MMedSci., PhD, FACSM Professor of Sport and Exercise Science University of Brighton and University of Rome “Foro Italico” Inspired? Then act… Rio Olympic Games – Athletics Where is Norway? “The Russian Olympic team corrupted the London Games 2012 on an unprecedented scale, the extent of which will probably never be fully established… The desire to win medals superseded their collective moral and ethical compass and Olympic values of fair play.” The reinstatement of Russia Olympic(s) in crisis Mike Poirier Collection Fairer Future for World-Class Sport of cleanthe athlete Protection 3P’s Deterrent effect of storage of samples for 10 years WADA CODE 2015 Fairer Future for World-Class Sport of cleanthe athlete Protection 3P’s A paradigm shift is needed In sport, the cheats are usually a step ahead GENE DOPING EXERCISE MGFs TRANSFUSIONS HGF FGFs CERA HEMATIDE MYO INHIBITORS ALTITUDE GH EPO CORTISOL TESTOSTERONE LH PPARd AICAR PDGF IGF-1 dEPO HIF CG VEGF COCKTAIL 1 SCO Group: 19 endurance trained males living and training at or near sea-level (Glasgow, Scotland) KEN Group: 20 Kenyan endurance runners living and training at moderate altitude ~2150 m (Eldoret, Kenya) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 weeks Blood sample Time trial/VO2max Time points selected for Gene expression Hbmass rHuEpo injection 50 IU∙kg-1 body mass analysis Haematocrit Future applicability? The Athlete Biological Passport? “abnormal” fluctuation “normal” fluctuation -

P12 3 Layout 1

12 Established 1961 Sports Sunday, May 6, 2018 Kiprop’s doping failure hits Kenya’s cradle of athletics Kenya’s most decorated athletes, could face a four-year ban ELDORET: The residents of Eldoret and Iten, consid- Kenya Executive Committee, defended the local gov- ered Kenya’s home of distance running, are hurting fol- erning body, saying Kenyans must accept that the lowing official confirmation that former Olympic and country has a doping problem. world 1,500 metres champion Asbel Kiprop has tested “Let us accept that there is a problem and agree on positive for the banned blood-booster EPO. how to tackle it. Blame game won’t help. Kenyans are The Athletics Integrity Unit (AIU), an independent still in denial yet this doping thing is festering,” he said. body handling doping matters on behalf of the sport’s “Athletes are not children. They are responsible for governing IAAF, earlier on Friday confirmed media what goes in their bodies. AK only sensitises and edu- reports that the 28-year-old three-time world champi- cates them on doping matters. They take full responsi- on over 1,500m had failed a dope test. bility for their actions,” he added. The case is now with an International Association of Athletics Federations’ disciplinary tribunal and the 28- KIPROP’S ALLEGATIONS year-old Kiprop, one of Kenya’s most decorated ath- Kiprop alleged that testers extorted money from letes, could face a four-year ban. There was a sombre him, an allegation the AIU did not address. He also mood on the Eldoret claimed that the testers streets among the local might have interfered people and in Iten, with his sample. -

RESULTS 1500 Metres Men - Final

London World Championships 4-13 August 2017 RESULTS 1500 Metres Men - Final RECORDS RESULT NAME COUNTRY AGE VENUE DATE World Record WR 3:26.00 Hicham EL GUERROUJ MAR 24 Roma (Stadio Olimpico) 14 Jul 1998 Championships Record CR 3:27.65 Hicham EL GUERROUJ MAR 25 Sevilla (La Cartuja) 24 Aug 1999 World Leading WL 3:28.80 Elijah Motonei MANANGOI KEN 24 Monaco (Stade Louis II) 21 Jul 2017 Area Record AR National Record NR Personal Best PB Season Best SB 13 August 2017 20:30 START TIME 22° C 35 % TEMPERATURE HUMIDITY PLACE NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH ORDER RESULT 1 Elijah Motonei MANANGOI KEN 5 Jan 93 2 3:33.61 2 Timothy CHERUIYOT KEN 20 Nov 95 7 3:33.99 3 Filip INGEBRIGTSEN NOR 20 Apr 93 6 3:34.53 4 Adel MECHAAL ESP 5 Dec 90 1 3:34.71 5 Jakub HOLUŠA CZE 20 Feb 88 4 3:34.89 6 Sadik MIKHOU BRN 25 Jul 90 10 3:35.81 7 Marcin LEWANDOWSKI POL 13 Jun 87 9 3:36.02 8 Nicholas WILLIS NZL 25 Apr 83 8 3:36.82 9 Asbel KIPROP KEN 30 Jun 89 11 3:37.24 10 John GREGOREK USA 7 Dec 91 3 3:37.56 11 Fouad ELKAAM MAR 27 May 88 12 3:37.72 12 Chris O'HARE GBR 23 Nov 90 5 3:38.28 INTERMEDIATE TIMES 400m 1128 Timothy CHERUIYOT 1:01.63 800m 1128 Timothy CHERUIYOT 1:57.59 1200m 1128 Timothy CHERUIYOT 2:53.68 ALL-TIME OUTDOOR TOP LIST SEASON OUTDOOR TOP LIST RESULT NAME VENUE DATE RESULT NAME VENUE 2017 3:26.00 Hicham EL GUERROUJ (MAR) Roma (Stadio Olimpico) 14 Jul 98 3:28.80 Elijah Motonei MANANGOI (KEN) Monaco (Stade Louis II) 21 Jul 3:26.34 Bernard LAGAT (KEN) Bruxelles 24 Aug 01 3:29.10 Timothy CHERUIYOT (KEN) Monaco (Stade Louis II) 21 Jul 3:26.69 Asbel KIPROP (KEN) -

Success on the World Stage Athletics Australia Annual Report 2010–2011 Contents

Success on the World Stage Athletics Australia Annual Report Success on the World Stage Athletics Australia 2010–2011 2010–2011 Annual Report Contents From the President 4 From the Chief Executive Officers 6 From The Australian Sports Commission 8 High Performance 10 High Performance Pathways Program 14 Competitions 16 Marketing and Communications 18 Coach Development 22 Running Australia 26 Life Governors/Members and Merit Award Holders 27 Australian Honours List 35 Vale 36 Registration & Participation 38 Australian Records 40 Australian Medalists 41 Athletics ACT 44 Athletics New South Wales 46 Athletics Northern Territory 48 Queensland Athletics 50 Athletics South Australia 52 Athletics Tasmania 54 Athletics Victoria 56 Athletics Western Australia 58 Australian Olympic Committee 60 Australian Paralympic Committee 62 Financial Report 64 Chief Financial Officer’s Report 66 Directors’ Report 72 Auditors Independence Declaration 76 Income Statement 77 Statement of Comprehensive Income 78 Statement of Financial Position 79 Statement of Changes in Equity 80 Cash Flow Statement 81 Notes to the Financial Statements 82 Directors’ Declaration 103 Independent Audit Report 104 Trust Funds 107 Staff 108 Commissions and Committees 109 2 ATHLETICS AuSTRALIA ANNuAL Report 2010 –2011 | SuCCESS ON THE WORLD STAGE 3 From the President Chief Executive Dallas O’Brien now has his field in our region. The leadership and skillful feet well and truly beneath the desk and I management provided by Geoff and Yvonne congratulate him on his continued effort to along with the Oceania Council ensures a vast learn the many and numerous functions of his array of Athletics programs can be enjoyed by position with skill, patience and competence. -

Bi-Weekly Bulletin 5-18 March 2019

INTEGRITY IN SPORT Bi-weekly Bulletin 5-18 March 2019 Photos International Olympic Committee INTERPOL is not responsible for the content of these articles. The opinions expressed in these articles are those of the authors and do not represent the views of INTERPOL or its employees. INTERPOL Integrity in Sport Bi-Weekly Bulletin 5-18 March 2019 SENTENCES/SANCTIONS Chile Mauricio Alvarez-Guzman banned for life for tennis match-fixing and associated corruption offences Chilean tennis player Mauricio Alvarez-Guzman has been handed a lifetime ban from professional tennis after being found guilty of match-fixing and associated corruption offences, which breach the sport’s Tennis Anti-Corruption Program (TACP). The 31-year old was found to have attempted to contrive the outcome of an August 2016 ATP Challenger match in Meerbusch, Germany by offering a player €1,000 to lose a set. In addition he was found guilty of contriving the singles draw of the ITF F27 Futures tournament played in July 2016 in Antalya, Turkey by purchasing a wild card for entry into the singles competition. An intention to purchase a wild card for the doubles competition of the same tournament did not come to fruition, but still stands as a corruption offence. The disciplinary case against Mr Alvarez-Guzman was considered by independent Anti-Corruption Hearing Officer Charles Hollander QC at a Hearing held in London on 11 March 2019. Having found him guilty of all charges, the lifetime ban imposed by Mr Hollander means that with effect from 14 March 2019 the player is permanently excluded from competing in or attending any tournament or event organised or sanctioned by the governing bodies of the sport. -

Athletics Chief Sebastian Coe And

SPORT Wednesday 9 August 2017 PAGE | 21 PAGE | 22 PAGE | 23 Golden McLeod Balanced England Stoke City’s Ireland restores Jamaican ccana win Ashes series, back in the game, sprint pride says du Plessis thanks to Aspetar Kiprop eyes El Guerrouj’s record four world titles London Reuters sbel Kiprop, Kenya’s three-time world champion over 1,500 metres, said yester- Aday that he has come to London to equal the four world titles of the Moroccan middle-dis- tance great Hicham El Guerrouj. The 28-year-old Kiprop, a former Olympic champion, hopes to get his fourth championship at the World Athletics Championships, before he moves on to 5,000m. “I want to become the first and only Kenyan to equal El Geurrouj’s four-title mark, then I move to 5,000m,” Kiprop told Reuters at the Kenyan team hotel in central London. His 1,500m cam- paign starts tomorrow. Qatari sprinter Abdalelah Haroun celebrates after British multiple world champion Mo Farah winning the bronze medal in the men’s 400 meters will again be the favourite in the men’s 5,000m event of the 2017 IAAF World Championships at when the qualification rounds start on Wednes- the London Stadium in London yesterday. day at the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Stadium. The last Kenyan to win the 5,000m was Benjamin Limo in 2005 in Helsinki. “We have a serious challenge in the 5,000m,” Kiprop said. “I hope and pray that I will be able to fulfil my ambition in the 1,500m before setting Haroun wins bronze my eyes on this event (5,000m).” Spotakova reclaims London Nathon Allen (Jamaica) in the diagnosed with an infectious dis- Agencies final stretch. -

Anti-Doping Rules

Book D – D3.1 ANTI-DOPING RULES (In force from 1 April 2020) Book D – D3.1 Book D – D3.1 Specific Definitions The words and phrases used in these Rules that are defined terms (denoted by initial capital letters) shall have the meanings specified in the Constitution and the Generally Applicable Definitions, or (in respect of the following words and phrases) the following meanings: "Athletics Integrity Unit" means the unit described in Part X of the Constitution and “Integrity Unit” has the same meaning. "ADAMS" The Anti-Doping Administration and Management System is a web-based database management tool for data entry, storage, sharing and reporting designed to assist Stakeholders and WADA in their anti-doping operations in conjunction with data protection legislation. "Administration" Providing, supplying, supervising, facilitating or otherwise participating in the Use or Attempted Use by another Person of a Prohibited Substance or Prohibited Method. However, this definition shall not include the actions of bona fide medical personnel involving a Prohibited Substance or Prohibited Method used for genuine and legal therapeutic purposes or other acceptable justification and shall not include actions involving Prohibited Substances which are not prohibited in Out-of-Competition Testing unless the circumstances as a whole demonstrate that such Prohibited Substances are not intended for genuine and legal therapeutic purposes or are intended to enhance sport performance. "Adverse Analytical Finding" A report from a WADA-accredited laboratory or other WADA- approved laboratory that, consistent with the International Standard for Laboratories and related Technical Documents, identifies in a Sample the presence of a Prohibited Substance or its Metabolites or Markers (including elevated quantities of endogenous substances) or evidence of the Use of a Prohibited Method. -

Procedural Rules

SR/Adhocsport/57/2019 IN THE MATTER OF PROCEEDINGS BROUGHT UNDER THE ANTI-DOPING RULES OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF ATHLETICS FEDERATIONS Before: Michael Beloff QC (Chair) Francisco A. Larios Jeffrey Benz BETWEEN: International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) Anti-Doping Organisation -and- Jarrion Lawson Respondent DECISION OF THE DISCIPLINARY TRIBUNAL A. INTRODUCTION 1. The Claimant, the International Association of Athletics Federations (“IAAF”), is the International Federation governing the sport of Athletics worldwide.1 It has its registered seat in Monaco. 2. The Respondent, Mr. Jarrion Lawson (the “Athlete”), is a 25-year-old American long jumper/sprinter. 3. On February 27, 2019, the Athletics Integrity Unit (“AIU”) charged the Athlete pursuant to Articles 2.1 and 2.2 of the IAAF Anti-Doping Rules (“ADR”) with an Anti-Doping Rule Violation (“ADRV’’) for the Presence and Use of a Prohibited Substance or its Metabolites or Markers, Epitrenbolone (a metabolite of Trenbolone). A. FACTUAL BACKGROUND 4. Below is a chronological summary of the undisputed evidence before the Disciplinary Tribunal (the “Tribunal”). 5. On April 11, 2018, the Athlete tested negative at a doping control test. 6. At all times between April 11, 2018 and June 2, 2018 he was subject to testing, during which period he competed on May 20, 2018 in the Seiko Golden Grand Prix Osaka 2018 in Osaka, Japan. 7. On June 2, 2018 in Springdale, Arkansas (USA), the Athlete underwent an Out-of- Competition doping control test following the Osaka meet. The Athlete provided a urine Sample with reference number 1609851 (the “Sample”). 8. On June 14, 2018, the A Sample was analysed by the WADA-accredited laboratory in Los Angeles, California (USA) (the “Laboratory”) and revealed the presence of Epitrenbolone (the “Adverse Analytical Finding” or “AAF”). -

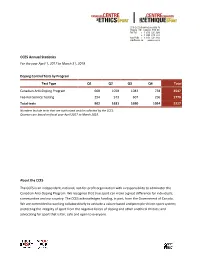

2017-2018 Doping Control Statistics

CCES Annual Statistics For the year April 1, 2017 to March 31, 2018 Doping Control Tests by Program Test Type Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Total Canadian Anti-Doping Program 668 1058 1083 738 3547 Fee-For-Service Testing 294 573 607 296 1770 Total tests 962 1631 1690 1034 5317 Numbers include tests that are authorized and/or collected by the CCES. Quarters are based on fiscal year April 2017 to March 2018. About the CCES The CCES is an independent, national, not-for-profit organization with a responsibility to administer the Canadian Anti-Doping Program. We recognize that true sport can make a great difference for individuals, communities and our country. The CCES acknowledges funding, in part, from the Government of Canada. We are committed to working collaboratively to activate a values-based and principle-driven sport system; protecting the integrity of sport from the negative forces of doping and other unethical threats; and advocating for sport that is fair, safe and open to everyone. Anti-Doping Rule Violations The following violations and sanctions were reported between April 1, 2017 and March 31, 2018. Athlete Sex Sport Violation Sanction Anderson- 2 months ineligibility M Athletics Presence: cannabis Richards, Tacuma Ends September 7, 2017 Arnaout, Presence: GW501516 and SARM S- 4 years ineligibility M Powerlifting Mohamad 22 Ends February 17, 2021 U SPORTS 1 year ineligibility Boucher, Bettina M Presence: ephedrine Track & Field Ends February 3, 2019 2 years ineligibility Chen, Ivan M Powerlifting Presence: D-amphetamine Ends October 15, 2019 -

All Time Men's World Ranking Leader

All Time Men’s World Ranking Leader EVER WONDER WHO the overall best performers have been in our authoritative World Rankings for men, which began with the 1947 season? Stats Editor Jim Rorick has pulled together all kinds of numbers for you, scoring the annual Top 10s on a 10-9-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1 basis. First, in a by-event compilation, you’ll find the leaders in the categories of Most Points, Most Rankings, Most No. 1s and The Top U.S. Scorers (in the World Rankings, not the U.S. Rankings). Following that are the stats on an all-events basis. All the data is as of the end of the 2019 season, including a significant number of recastings based on the many retests that were carried out on old samples and resulted in doping positives. (as of April 13, 2020) Event-By-Event Tabulations 100 METERS Most Points 1. Carl Lewis 123; 2. Asafa Powell 98; 3. Linford Christie 93; 4. Justin Gatlin 90; 5. Usain Bolt 85; 6. Maurice Greene 69; 7. Dennis Mitchell 65; 8. Frank Fredericks 61; 9. Calvin Smith 58; 10. Valeriy Borzov 57. Most Rankings 1. Lewis 16; 2. Powell 13; 3. Christie 12; 4. tie, Fredericks, Gatlin, Mitchell & Smith 10. Consecutive—Lewis 15. Most No. 1s 1. Lewis 6; 2. tie, Bolt & Greene 5; 4. Gatlin 4; 5. tie, Bob Hayes & Bobby Morrow 3. Consecutive—Greene & Lewis 5. 200 METERS Most Points 1. Frank Fredericks 105; 2. Usain Bolt 103; 3. Pietro Mennea 87; 4. Michael Johnson 81; 5. -

Table of Contents

A Column By Len Johnson TABLE OF CONTENTS TOM KELLY................................................................................................5 A RELAY BIG SHOW ..................................................................................8 IS THIS THE COMMONWEALTH GAMES FINEST MOMENT? .................11 HALF A GLASS TO FILL ..........................................................................14 TOMMY A MAN FOR ALL SEASONS ........................................................17 NO LIGHTNING BOLT, JUST A WARM SURPRISE ................................. 20 A BEAUTIFUL SET OF NUMBERS ...........................................................23 CLASSIC DISTANCE CONTESTS FOR GLASGOW ...................................26 RISELEY FINALLY GETS HIS RECORD ...................................................29 TRIALS AND VERDICTS ..........................................................................32 KIRANI JAMES FIRST FOR GRENADA ....................................................35 DEEK STILL WEARS AN INDELIBLE STAMP ..........................................38 MICHAEL, ELOISE DO IT THEIR WAY .................................................... 40 20 SECONDS OF BOLT BEATS 20 MINUTES SUNSHINE ........................43 ROWE EQUAL TO DOUBELL, NOT DOUBELL’S EQUAL ..........................46 MOROCCO BOUND ..................................................................................49 ASBEL KIPROP ........................................................................................52 JENNY SIMPSON .....................................................................................55 -

The Sub-4 Alphabetic Register (1,338 Athletes As at 27 April 2014)

The Sub-4 Alphabetic Register (1,338 athletes as at 27 April 2014) No country has kept greater faith with the legend of the sub-four-minute mile than the USA. Duing the 2014 indoor season in that country 48 athletes broke four minutes and the US total of sub- four-minute milers is now approaching the 450 mark. Elsewhere, even the distant past eventually yields its secrets: a hitherto overlooked performance from as long ago as 1974 by a Bulgarian was not discovered until 36 years later ! There are now 17 sets of brothers, including five sets of twins, and five sets of fathers and sons who have broken four minutes. The most recent contributor to this family tradition is John Coghlan, son of Eamonn Coghlan. No grandfathers and grandsons as yet ! Performances listed in this Register represent the first occasion on which the athlete ran sub-four- minutes for the mile, followed by the all-time personal best if there was a subsequent improvement. Almost 60 per cent of the 1,338 athletes listed have not bettered their first Sub-4 performance, though some of those from the more recent years will obviously do so eventually. Performances listed in tenths-of-a-second were recorded manually; it may be that some of these were also automatically recorded and the figures not made public, but as they mostly date back 30 years or more it is very unlikely that such data will ever come to light. The standard middle- distance event in international competition has for more than a century been the 1500 metres, and but for this there would certainly be twice as many sub-four-minute milers as there actually are.