Procedural Rules

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 US Olympic Trials Statistics – Men’S LJ by K Ken Nakamura

2020 US Olympic Trials Statistics – Men’s LJ by K Ken Nakamura Summary: All time performance list at the Olympic Trials Performance Performer Dist Wind Name Pos Venue Year 1 1 8.76 0.8 Carl Lewis 1 Indianapolis 1988 2 2 8.74 1.4 Larry Myricks 2 Indianapolis 1988 3 8.71 0.1 Carl Lewis 1 Los Angeles 1984 4 3 8.62 0.0 Mike Powell 1 New Orleans 1992 5 4 8.58 1.8 Jarrion Lawson 2 Eugene 2016 6 8. 53 0.0 Carl Lewis 2 New Orleans 1992 7 5 8.42 1.6 Marquis Dendy 4 Eugene 2016 8 8.39 ? Carl Lewis 1q Los Angeles 1984 Margin of Victory Difference Winning Dist wind Name Venue Year Max 46 cm 8.71 0.1 Carl Lewis Los Angeles 1984 Min 1cm 8.59 2.9 Jeff Henderson Eugene 2016 2cm 8.04 1.0 Arnie Robinson Eugene 1972 8.76 0.8 Carl Lewis Indianapolis 1988 Best Marks for Places in the Olympic Trials Pos Dist Wind Name Venue Year 1 8.76 0.8 Carl Lewis Indianapolis 1988 2 8.74 1.4 Larry Myricks Indianapolis 1988 3 8.42 5.0 Will Claye Eugene 2016 8.30 -0.2 Carl Lewis Atlanta 1996 8.36w 2.8 Mike Powell Indianapolis 1988 4 8.42 1.6 Marquis Dendy Eugene 2016 8.27 0.2 Mike Conley Atlanta 1996 8.31w 3.1 Gordon Laine Indianapolis 1988 Last five Olympic Trials Year First Dist Second Dist Third Dist 2016 Jeff Henderson 8.59w Jarrion Lawson 8.58 Will Claye 8.42w 2012 Marquise Goodwin 8.33 Will Claye 8.23w George Kitchens 8.21 2008 Trevell Quinley 8.36 Brian Johnson 8.30 Miguel Pate 8.22 2004 Dwight Phillips 8.28 Tony Allmond 8.10 John Moffitt 8.07 2000 Melvin Lister 8.32 Dwight Phillips 8.14 Walter Davis 8.11 All time US List Performance Performer Dist wind Name Pos Venue DMY 1 1 8.95 0.3 Mike Powell 1 Tokyo 30 Aug 1991 2 2 8.90 2.0 Bob Beamon 1 Mexico Cit y 18 Oc t 1968 3 3 8.87 -0.2 Carl Lewis 2 Tokyo 30 Aug 1991 Longest jumps in Eugene Performance Performer Dist wind Name Nat Pos DMY 1 1 8.74 -1.2 Dwight Phillips USA 1 7 June 2009 2 2 8.63 -0.4 Irving Saladino PAN 2 7 June 2009 8.58 1.8 Jarrion Law son USA 2 3 July 2016 3 3 8.49 1.7 Mike Po well USA 19 June 1993 Note: None of the ancillary marks are included in the table. -

Division I Men's Outdoor Track Championships Records Book

DIVISION I MEN’S OUTDOOR TRACK CHAMPIONSHIPS RECORDS BOOK 2020 Championship 2 History 2 All-Time Team Results 30 2020 CHAMPIONSHIP The 2020 championship was not contested due to the COVID-19 pandemic. HISTORY TEAM RESULTS (Note: No meet held in 1924.) †Indicates fraction of a point. *Unofficial champion. Year Champion Coach Points Runner-Up Points Host or Site 1921 Illinois Harry Gill 20¼ Notre Dame 16¾ Chicago 1922 California Walter Christie 28½ Penn St. 19½ Chicago 1923 Michigan Stephen Farrell 29½ Mississippi St. 16 Chicago 1925 *Stanford R.L. Templeton 31† Chicago 1926 *Southern California Dean Cromwell 27† Chicago 1927 *Illinois Harry Gill 35† Chicago 1928 Stanford R.L. Templeton 72 Ohio St. 31 Chicago 1929 Ohio St. Frank Castleman 50 Washington 42 Chicago 22 1930 Southern California Dean Cromwell 55 ⁄70 Washington 40 Chicago 1 1 1931 Southern California Dean Cromwell 77 ⁄7 Ohio St. 31 ⁄7 Chicago 1932 Indiana Billy Hayes 56 Ohio St. 49¾ Chicago 1933 LSU Bernie Moore 58 Southern California 54 Chicago 7 1934 Stanford R.L. Templeton 63 Southern California 54 ⁄20 Southern California 1935 Southern California Dean Cromwell 741/5 Ohio St. 401/5 California 1936 Southern California Dean Cromwell 103⅓ Ohio St. 73 Chicago 1937 Southern California Dean Cromwell 62 Stanford 50 California 1938 Southern California Dean Cromwell 67¾ Stanford 38 Minnesota 1939 Southern California Dean Cromwell 86 Stanford 44¾ Southern California 1940 Southern California Dean Cromwell 47 Stanford 28⅔ Minnesota 1941 Southern California Dean Cromwell 81½ Indiana 50 Stanford 1 1942 Southern California Dean Cromwell 85½ Ohio St. 44 ⁄5 Nebraska 1943 Southern California Dean Cromwell 46 California 39 Northwestern 1944 Illinois Leo Johnson 79 Notre Dame 43 Marquette 3 1945 Navy E.J. -

— 2016 T&FN Men's U.S. Rankings —

50K WALK — 2016 T&FN Men’s U.S. Rankings — 1. John Nunn 2. Nick Christie 100 METERS 1500 METERS 110 HURDLES 3. Steve Washburn 1. Justin Gatlin 1. Matthew Centrowitz 1. Devon Allen 4. Mike Mannozzi 2. Trayvon Bromell 2. Ben Blankenship 2. David Oliver 5. Matthew Forgues 3. Marvin Bracy 3. Robby Andrews 3. Ronnie Ash 6. Ian Whatley 4. Mike Rodgers 4. Leo Manzano 4. Jeff Porter HIGH JUMP 5. Tyson Gay 5. Colby Alexander 5. Aries Merritt 1. Erik Kynard 6. Ameer Webb 6. Johnny Gregorek 6. Jarret Eaton 2. Kyle Landon 7. Christian Coleman 7. Kyle Merber 7. Jason Richardson 3. Deante Kemper 8. Jarrion Lawson 8. Clayton Murphy 8. Aleec Harris 4. Bradley Adkins 9. Dentarius Locke 9. Craig Engels 9. Spencer Adams 5. Trey McRae 10. Isiah Young 10. Izaic Yorks 10. Adarius Washington 6. Ricky Robertson 200 METERS STEEPLE 400 HURDLES 7. Dakarai Hightower 1. LaShawn Merritt 1. Evan Jager 1. Kerron Clement 8. Trey Culver 2. Justin Gatlin 2. Hillary Bor 2. Michael Tinsley 9. Bryan McBride 3. Ameer Webb 3. Donn Cabral 3. Byron Robinson 10. Randall Cunningham 4. Noah Lyles 4. Andy Bayer 4. Johnny Dutch POLE VAULT 5. Michael Norman 5. Mason Ferlic 5. Ricky Babineaux 1. Sam Kendricks 6. Tyson Gay 6. Cory Leslie 6. Jeshua Anderson 2. Cale Simmons 7. Sean McLean 7. Stanley Kebenei 7. Bershawn Jackson 3. Logan Cunningham 8. Kendal Williams 8. Donnie Cowart 8. Quincy Downing 4. Mark Hollis 9. Jarrion Lawson 9. Dan Huling 9. Eric Futch 5. Jake Blankenship 10. -

BCSP Notes CLARK ATLANTA Vs

FOR THE WEEK OF AUGUST 16 - 22, 2016 Henderson wins Rio long jump; Promises more Former Stillman trackster Jeff Henderson won the long jump at the 2016 Rio Olympic Games on his sixth and final attempt, leaping a season- ™ best 27 feet, 6 inches (8.38 meters). He hit the sand, then bounded out the back of the pit and sprinted down the tarmac. After he saw his mark, he then sprinted the other way in elation. His final jump eclipsed Luvo Manyonga of South Africa by half an inch or one centimeter. Manyonga had jumped 8.37 meters before Hen- derson's jump. Rio Olympic Photo Henderson's was the first gold for Team USA in this event since 2004. JEFF HENDERSON: Teammate Jarrion Lawson was fourth at 27-0 ¾, finishing behind OPENING Former Stillman track reigning Olympic champion Greg Rutherford of Great Britain, who over- EYES star takes long jump gold medal on final jump at Rio took him on his final attempt by jumping 27-2 ½. IN RIO Olympics. After winning the gold medal, Henderson got an unexpected history lesson. HENDERSON WINS LONG JUMP IN RIO; BCSP An Olympic official opened his press conference by announcing that the United States has won 22 gold medals in the long jump, more gold PRESEASON FOOTBALL A-A; HOMECOMINGS medals won by any country in any event. "I did not know about that until now," said Henderson, 27, from McAlmont, Ark. "But it feels good to be in that category, to win that many medals. It feels surreal right now.’" UNDER THE BANNER Oh, and one more thing he wanted to add. -

Texas Track & Field and Cross Country

TEXAS TRACK & FIELD AND CROSS COUNTRY Contact: David Wiechmann | [email protected] | O: 512-471-6062 | C: 936-234-2711 6 NCAA Indoor Championships | 4 NCAA Outdoor Championships | 1 NCAA XC Championship 16 Big 12 Conference Indoor Championships | 17 Big 12 Conference Outdoor Championships COACHING STAFF 90TH CLYDE LittlEFIELD TEXAS RElaYS PRESENTED BY SPEctrUM DATE: March 29-April 1 Head Coach _____________________ Mario Sategna LOcatiON: Austin, Texas Associate Head Coach - Sprints/Hurdles __ Tonja Buford-Bailey facilitY: Mike A. Myers Stadium Assistant Coach - Field Events _______________ Ty Sevin TwittER: @TexasTFXC | #HookEm | #TXRelays17 LIVE RESUlts: BranchTiming.com Assistant Coach - Distance/XC ____________Brad Herbster TV: Longhorn Network | Check local listings for dialy coverage Assistant Coach - Jumps/Multis ___________ Seth Henson Assistant Coach - Sprints _______________ Zach Glavash Texas Track & Field has an exciting week of action ahead as the Longhorns host the 90th Clyde Littlefield Texas Relays, Director of Operations ________________LaVera Morris presented by Spectrum. This year’s meet is the biggest in its stories history with more than 7,700 athletes entered to Volunteer Assistant - Distance/XC __________ James Croft compete at Mike A. Myers Stadium over the four days. Twitter: @TexasTFXC | Instagram: utexastrackfieldxc Olympic medalists, NCAA champions, current, former and future Longhorns will face athletes from across the nation in what will be another spectacular week of track and field. 2017 SCHEDULE INDOOR Action starts at 10:30 a.m. Wednesday when athletes competing in the heptathlon and decathlon begin their two January days of battle. The field includes Olympic silver medalist and Lifetime Longhorn Trey Hardee. Thursday’s action will 13-14 Texas A&M Team Invitational College Station, Texas feature the conclusion of the multi-events along with a few field events, mid-distance races and the steeplechase. -

Bi-Weekly Bulletin 5-18 March 2019

INTEGRITY IN SPORT Bi-weekly Bulletin 5-18 March 2019 Photos International Olympic Committee INTERPOL is not responsible for the content of these articles. The opinions expressed in these articles are those of the authors and do not represent the views of INTERPOL or its employees. INTERPOL Integrity in Sport Bi-Weekly Bulletin 5-18 March 2019 SENTENCES/SANCTIONS Chile Mauricio Alvarez-Guzman banned for life for tennis match-fixing and associated corruption offences Chilean tennis player Mauricio Alvarez-Guzman has been handed a lifetime ban from professional tennis after being found guilty of match-fixing and associated corruption offences, which breach the sport’s Tennis Anti-Corruption Program (TACP). The 31-year old was found to have attempted to contrive the outcome of an August 2016 ATP Challenger match in Meerbusch, Germany by offering a player €1,000 to lose a set. In addition he was found guilty of contriving the singles draw of the ITF F27 Futures tournament played in July 2016 in Antalya, Turkey by purchasing a wild card for entry into the singles competition. An intention to purchase a wild card for the doubles competition of the same tournament did not come to fruition, but still stands as a corruption offence. The disciplinary case against Mr Alvarez-Guzman was considered by independent Anti-Corruption Hearing Officer Charles Hollander QC at a Hearing held in London on 11 March 2019. Having found him guilty of all charges, the lifetime ban imposed by Mr Hollander means that with effect from 14 March 2019 the player is permanently excluded from competing in or attending any tournament or event organised or sanctioned by the governing bodies of the sport. -

2021 Track & Field Record Book

2021 TRACK & FIELD RECORD BOOK 1 Mondo broke his own world record with a clearance of 6.18 meters in Glasgow, Scotland, on February 15, 2020. 2020 World Athletics Male Athlete of the Year Baton Rouge, La. – Mondo Duplantis was named Renaud Lavilennie’s previous world record of 6.14 Greg, were given the Coaching Achievement Award. the winner of the 2020 World Athletics Male Athlete of meters that was set in 2014. Helena and Greg serve as Mondo’s coaches and the Year award on December 5, 2020. The virtual cer- It was only a week later and he re-upped his world training advisors; Greg still serves as a volunteer emony announced a plethora of awards in what was a record by a centimeter with a clearance of 6.18 meters assistant coach with the LSU track and field program. celebration of the sport of track and field. on February 15 at the Muller Indoor Grand Prix in Mondo also was part of an award that was won by Mondo won the award over Joshua Cheptegei Glasgow. The indoor season saw him compete five Renaud Lavillenie – the COVID Inspiration award. In the (Uganda), Ryan Crouser (USA), Johannes Vetter times and at each event he cleared six meters or early stages of COVID-19 lockdowns, Lavillenie came (Germany), and Karsten Warholm (Norway). Duplantis, higher. up with the concept of the ‘Ultimate Garden Clash’. It who is 21 years old, becomes the youngest winner of Following a three and a half month hiatus due was event that three pole vaulters – Lavillenie, Mondo, this award. -

Anti-Doping Rules

Book D – D3.1 ANTI-DOPING RULES (In force from 1 April 2020) Book D – D3.1 Book D – D3.1 Specific Definitions The words and phrases used in these Rules that are defined terms (denoted by initial capital letters) shall have the meanings specified in the Constitution and the Generally Applicable Definitions, or (in respect of the following words and phrases) the following meanings: "Athletics Integrity Unit" means the unit described in Part X of the Constitution and “Integrity Unit” has the same meaning. "ADAMS" The Anti-Doping Administration and Management System is a web-based database management tool for data entry, storage, sharing and reporting designed to assist Stakeholders and WADA in their anti-doping operations in conjunction with data protection legislation. "Administration" Providing, supplying, supervising, facilitating or otherwise participating in the Use or Attempted Use by another Person of a Prohibited Substance or Prohibited Method. However, this definition shall not include the actions of bona fide medical personnel involving a Prohibited Substance or Prohibited Method used for genuine and legal therapeutic purposes or other acceptable justification and shall not include actions involving Prohibited Substances which are not prohibited in Out-of-Competition Testing unless the circumstances as a whole demonstrate that such Prohibited Substances are not intended for genuine and legal therapeutic purposes or are intended to enhance sport performance. "Adverse Analytical Finding" A report from a WADA-accredited laboratory or other WADA- approved laboratory that, consistent with the International Standard for Laboratories and related Technical Documents, identifies in a Sample the presence of a Prohibited Substance or its Metabolites or Markers (including elevated quantities of endogenous substances) or evidence of the Use of a Prohibited Method. -

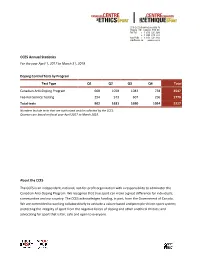

2017-2018 Doping Control Statistics

CCES Annual Statistics For the year April 1, 2017 to March 31, 2018 Doping Control Tests by Program Test Type Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Total Canadian Anti-Doping Program 668 1058 1083 738 3547 Fee-For-Service Testing 294 573 607 296 1770 Total tests 962 1631 1690 1034 5317 Numbers include tests that are authorized and/or collected by the CCES. Quarters are based on fiscal year April 2017 to March 2018. About the CCES The CCES is an independent, national, not-for-profit organization with a responsibility to administer the Canadian Anti-Doping Program. We recognize that true sport can make a great difference for individuals, communities and our country. The CCES acknowledges funding, in part, from the Government of Canada. We are committed to working collaboratively to activate a values-based and principle-driven sport system; protecting the integrity of sport from the negative forces of doping and other unethical threats; and advocating for sport that is fair, safe and open to everyone. Anti-Doping Rule Violations The following violations and sanctions were reported between April 1, 2017 and March 31, 2018. Athlete Sex Sport Violation Sanction Anderson- 2 months ineligibility M Athletics Presence: cannabis Richards, Tacuma Ends September 7, 2017 Arnaout, Presence: GW501516 and SARM S- 4 years ineligibility M Powerlifting Mohamad 22 Ends February 17, 2021 U SPORTS 1 year ineligibility Boucher, Bettina M Presence: ephedrine Track & Field Ends February 3, 2019 2 years ineligibility Chen, Ivan M Powerlifting Presence: D-amphetamine Ends October 15, 2019 -

Track & Field and Cross Country

Texas Track & Field and Cross Country Contact: David Wiechmann | [email protected] | O: 512-471-6062 | C: 936-234-2711 6 NCAA Indoor Championships | 4 NCAA Outdoor Championships 15 Big 12 Conference Indoor Championships | 15 Big 12 Conference Outdoor Championships COachiNG STAFF NCAA CHAMPIONSHIPS daTE: March 11-12 LOcaTION: Birmingham, Ala. Director of Track & Field and Cross Country ___ Mario Sategna faciliTY: Birmingham CrossPlex Associate Head Coach - Sprints _______ Tonja Buford-Bailey TwiTTER: @UTexasTrack | @NCAATrackField Assistant Coach - Distance/XC ____________Brad Herbster LIVE RESULTS: FlashResults.com LIVE VIDEO: ESPN3.com: Friday 5:25 pm | Saturday 3:55 pm Assistant Coach - Sprints _______________ Seth Henson Assistant Coach - Field Events _______________ Ty Sevin Texas Track & Field heads to Birmingham, Alabama, this weekend as the Longhorns will face the best the nation Assistant Coach - Jumps _______Kareem Streete-Thompson has to offer at the NCAA Indoor Track & Field Championships. Action gets underway on Friday from the Birmingham Director of Operations ________________LaVera Morris CrossPlex with Texas looking for a handful of individual titles and a team championship to go with them. Twitter: @UTexasTrack The women’s team enters the meet ranked No. 5 in the latest USTFCCCA Rankings. MOST NCAA ENTRIES Instagram: utexastrackfieldxc The men stand in at seventh. Both teams finished sixth at last year’s champion- MEN ENTRIES ship meet and return a number of veterans who could make a big impact on the Arkansas 12 2016 SCHEDULE team standings. OREGON, Texas A&M 10 Florida 8 Senior Courtney Okolo is the defending champion in the 400 meters and juco LSU 7 INDOOR champion Chrisann Gordon joins her in the mix for Texas this year. -

Top TFRRS Qualifiers

NCAA Division I - Top 10 Seeds by Event as of February 15 MEN 60 Meters 800 Meters 1 Christian COLEMAN SO Tennessee 6.54 Feb 5 1 Donavan BRAZIER FR Texas A&M 1:45.93 Jan 15 1 John TEETERS JR Oklahoma State 6.54 Jan 29 2 Clayton MURPHY JR Akron 1:46.13 OT Feb 12 3 Cameron BURRELL JR Houston 6.55 Jan 15 3 Eliud RUTTO JR Middle Tennessee 1:46.87 OT Feb 12 4 Ronnie BAKER SR TCU 6.58 Feb 12 4 Shaquille WALKER JR BYU 1:46.97 OT Jan 29 5 Markesh WOODSON SR Missouri 6.59 Feb 12 5 Brannon KIDDER SR Penn State 1:47.01 Jan 29 6 Bryce ROBINSON SR Tulsa 6.62 Jan 22 6 Drew PIAZZA JR New Hampshire 1:47.28 Jan 29 6 Jarrion LAWSON SR Arkansas 6.62 Jan 29 7 Isaiah HARRIS FR Penn State 1:47.31 Feb 5 8 Tevin HESTER SR Clemson 6.63 Jan 9 8 Ryan MANAHAN JR Mississippi 1:47.37 Jan 29 8 Arman HALL SR Florida 6.63 Jan 22 9 Carlton ORANGE FR Arkansas 1:47.38 Jan 29 10 Leshon COLLINS SR Houston 6.64 Jan 15 10 Andres ARROYO JR Florida 1:47.43 OT Jan 22 10 Ryan CLARK FR Florida 6.64 Feb 12 Mile 10 Kenzo COTTON SO Arkansas 6.64 Jan 15 1 Justyn KNIGHT FR Syracuse 3:56.87 Jan 29 10 Brandon CARNES JR Northern Iowa 6.64 Feb 5 2 Futsum JR Northern Arizona 3:56.98cA OT 4:05.92 Jan 29 200 Meters ZIENASELLASSIE 3 Clayton MURPHY JR Akron 3:57.11 OT Feb 5 1 Brendon RODNEY SR LIU Brooklyn 20.52 Feb 12 4 David ELLIOTT SR Boise State 3:57.38 OT Feb 12 2 Nethaneel JR LSU 20.57 Jan 22 MITCHELL-BLAKE 4 Edward CHESEREK JR Oregon 3:57.38 Jan 29 3 Devin JENKINS SR Texas A&M 20.58 Feb 5 6 Jacob BURCHAM JR Oklahoma 3:57.46 OT Feb 12 4 Christian COLEMAN SO Tennessee 20.59 Feb 12 7 Morgan -

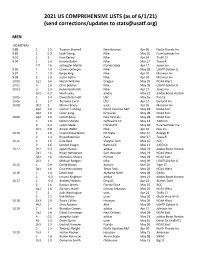

06-01-21 Us Comprehensive Lists

2021 US COMPREHENSIVE LISTS (as of 6/1/21) (send corrections/updates to [email protected]) MEN 100 METERS 9.88 1 1.5 Trayvon Bromell New Balance Apr 30 North Florida Inv 9.89 1 0.2 Isiah YounG Nike May 30 Pure Summer Inv 9.91 1 2 Fred Kerley Nike Apr 24 TruFit Cl 9.94 1 1.4 Ronnie Baker Nike Mar 27 Texas R 1f2 1.6 JoVauGhn Martin Florida State Apr 17 Jones Inv 9.96 1 1.9 Cravon Gillespie Nike May 09 USATF Golden G 9.97 1 1.9 Kyree KinG Nike Apr 10 Miramar Inv 9.98 2 1.9 Justin Gatlin Nike Apr 10 Miramar Inv 10.00 1q1 1.6 Micah Williams OreGon May 29 NCAA West 10.01 3 1.9 Chris Belcher Nike May 09 USATF Golden G 10.03 3 1.4 Kenny Bednarek Nike Apr 17 Jones Inv 1h2 0.3 Noah Lyles adidas May 23 adidas Boost Boston 10.05 1 1.4 Davonte Burnett USC May 16 Pac-12 10.06 1 1.7 Terrance Laird LSU Apr 17 Garland Inv 10.08 3h2 2 Marvin Bracy unat Apr 10 Miramar Inv 2q2 1.6 Javonte HardinG North Carolina A&T May 28 NCAA East 3q2 1.6 Lance LanG Kentucky May 28 NCAA East 10.09 4q2 1.6 Ismael Kone New Orleans May 28 NCAA East 1 1.6 Nolton Shelvin Coffeyville CC May 13 JUCO Ch 3 0.2 Jaylen Slade Florida HS May 30 Pure Summer Inv 1h1 0.8 Ameer Webb Nike Apr 16 Clay Inv 10.10 1 1.6 Cravont Charleston NC State Mar 27 Raleigh R 2 1.4 Bryce Robinson Asics Mar 27 Texas R 10.11 1 1.6 Cole Beck Virginia Tech May 15 ACC 2 1.6 Denzell FeaGin Barton CC May 13 JUCO Ch 10.12 2h2 0.3 Jaylen Bacon adidas May 23 adidas Boost Boston 2q1 1.6 Bryan Henderson Sam Houston May 29 NCAA West 5q2 1.6 Marcellus Moore Purdue May 28 NCAA East 2h2 1 Michael RodGers Nike May 09 USATF