Nicole Lawrence Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Florida Future, Vol. 39 No. 23, October 13, 2006

University of Central Florida STARS Central Florida Future University Archives 10-13-2006 Central Florida Future, Vol. 39 No. 23, October 13, 2006 Part of the Mass Communication Commons, Organizational Communication Commons, Publishing Commons, and the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Central Florida Future by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation "Central Florida Future, Vol. 39 No. 23, October 13, 2006" (2006). Central Florida Future. 1956. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture/1956 SECRET GARDENS UCF arboretum will TWO'S COMPANY take students on a trip Senior Steven Moffett and junior Kyle Israel will around the world. both see action today against Pittsburgh-sEESPORTS,A7 - SEE NEWS, A2 FREE • Published Monda s, Wednesda sand Frida s www.CentralFloridaFuture.com ·Friday, o"ctober 13, 2006 Only one med dean candidate UCF must hire last woman_standing or continue its search ROBYN SIDERSKY · Contributing Writer UCF announced Wedn~t Dr. Thomas Schwenk has dropped out of the race for the founding d~UCFs. med ical school, leaving only one offive original candidates for consideration. Schwenk is currently a professor and chair of the Department-of Family Medi cine at the University of Michigan Medical School Although he declinecfto be interviewed, he said that he is "not interested in debating 1:1).e financial or other issues affecting the success ofthe medical school" Recently, three other candidates in the running to be the dean of the medical school have withdrawn their candidacies - Dr. -

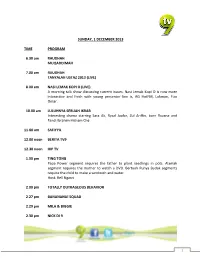

1 SUNDAY, 1 DECEMBER 2013 TIME PROGRAM 6.30 Am

SUNDAY, 1 DECEMBER 2013 TIME PROGRAM 6.30 am RAUDHAH MUQADDIMAH 7.00 am RAUDHAH TANYALAH USTAZ 2013 (LIVE) 8.00 am NASI LEMAK KOPI O (LIVE) A morning talk show discussing current issues. Nasi Lemak Kopi O is now more interactive and fresh with young presenter line is, AG HotFM, Lokman, Fizo Omar. 10.00 am LULUHNYA SEBUAH IKRAR Interesting drama starring Sara Ali, Ryzal Jaafar, Zul Ariffin, born Ruzana and Fandi Ibrahim Hisham Che 11.00 am SAFIYYA 12.00 noon BERITA TV9 12.30 noon HIP TV 1.00 pm TING TONG Papa Power segment requires the father to plant seedlings in pots. Alamak segment requires the mother to watch a DVD. Bertuah Punya Budak segments require the child to make a sandwich and water. Host: Bell Ngasri 2.00 pm TOTALLY OUTRAGEOUS BEHAVIOR 2.27 pm BANANANA! SQUAD 2.29 pm MILA & BIGGIE 2.30 pm NICK DI 9 1 TEAM UMIZOOMI 3.00 pm NICK DI 9 DORA THE EXPLORER 3.30 pm NICK DI 9 ADVENTURES OF JIMMY NEUTRONS 4.00 pm NICK DI 9 PLANET SHEEN 4.30 pm NICK DI 9 AVATAR THE LEGEND OF AANG 5.00 pm NICK DI 9 SPONGEBOB SQUAREPANTS 5.28 pm BANANANA! SQUAD 5.30 pm BOLA KAMPUNG THE MOVIE Amanda is a princess who comes from the virtual world of a game called "Kingdom Hill '. She was sent to the village to find Pewira Suria, the savior who can end the current crisis. Cast: Harris Alif, Aizat Amdan, Harun Salim Bachik, Steve Bone, Ezlynn 7.30 pm SWITCH OFF 2 The Award Winning game show returns with a new twist! Hosted by Rockstar, Radhi OAG, and the game challenges bands with a mission to save their band members from the Mysterious House in the Woods. -

Cutting Patterns in DW Griffith's Biographs

Cutting patterns in D.W. Griffith’s Biographs: An experimental statistical study Mike Baxter, 16 Lady Bay Road, West Bridgford, Nottingham, NG2 5BJ, U.K. (e-mail: [email protected]) 1 Introduction A number of recent studies have examined statistical methods for investigating cutting patterns within films, for the purposes of comparing patterns across films and/or for summarising ‘average’ patterns in a body of films. The present paper investigates how different ideas that have been proposed might be combined to identify subsets of similarly constructed films (i.e. exhibiting comparable cutting structures) within a larger body. The ideas explored are illustrated using a sample of 62 D.W Griffith Biograph one-reelers from the years 1909–1913. Yuri Tsivian has suggested that ‘all films are different as far as their SL struc- tures; yet some are less different than others’. Barry Salt, with specific reference to the question of whether or not Griffith’s Biographs ‘have the same large scale variations in their shot lengths along the length of the film’ says the ‘answer to this is quite clearly, no’. This judgment is based on smooths of the data using seventh degree trendlines and the observation that these ‘are nearly all quite different one from another, and too varied to allow any grouping that could be matched against, say, genre’1. While the basis for Salt’s view is clear Tsivian’s apparently oppos- ing position that some films are ‘less different than others’ seems to me to be a reasonably incontestable sentiment. It depends on how much you are prepared to simplify structure by smoothing in order to effect comparisons. -

Avatar the Last Air Bender Powerpoint

Ashley Williams, Ginny Nordeng, and Mayela Milian-Hernandez Overview of Presentation ● Anthropology ○ Confucius ○ Filial Piety ● Psychodynamic Theory ○ The younger years of Katara/Sokka, Aang, and Zuko/Azul ● Social Learning Theory ○ The Journey of Sokka, Zuko/Azula and Aang Anthropology is how different cultures view gender(Wood & Fixmer-Oraiz, 2017) https://www.biography.com/scholar/confucius Four nations: Earth, Fire, Water, and Air http://avatar-the-last-airbender-online.blogspot.com/2010/08/avatar-last-airbender-airbender-world.html Filial Piety is the confucius belief of respecting one’s parents, elders and ancestors.(Bedford et al 2019) https://www.bookofdaystales.com/confucius/ https://www.pinterest.com/pin/346495765052132139/ https://avatar.fandom.com/wiki/Iroh https://avatar.fandom.com/wiki/Oza Filial Piety Favoring the intimate, the people closest to you and Respecting the superior; the people with higher authority to you. (Bedford et al 2019) Men and Women represent Yin and Yang In order to keep balance men and women must have separate roles. Men Lead, Women Follow…(Ebry 2019) https://www.deviantart.com/karinart8/art/Ying-and-Yang-283381659 Yin and Yang In the Northern Tribe, the master/teacher refuses to teach women how to bend. It is not their place.. In the southern tribe, All the Men left to fight a war with the fire nation. Women only allowance of leadership Psychodynamic is the first relationship one has to define their gender identity (Wood & Fixmer-Oraiz, 2017) http://thatanimatedotaku. blogspot.com/2013/07/a nimated-role-models-girl s.html http://audreymgonzalez.com/2012/book-three-fire-chapter-twelve-the-w estern-air-temple/ Katara and Sokka Katara has a close relationship with her grandmother. -

Prepare to Loaf out Loud As Nickelodeon Delivers New Animation Breadwinners

PREPARE TO LOAF OUT LOUD AS NICKELODEON DELIVERS NEW ANIMATION BREADWINNERS Expect hilarious escapades, high energy and booty-shaking music in plucky new series Breadwinners, premiering on Monday 22nd September at 4:30pm only on Nicktoons London, 20th August 2014 – New animated comedy Breadwinners follows SwaySway and Buhdeuce, two hilarious ducks who operate a bread delivery service out of their jet-fueled, Rocket Van, feeding hungry beaks everywhere. Breadwinners is an original production from the Nickelodeon Animation Studios and will premiere on Monday 22nd September at 4:30pm on Nicktoons. Throughout the series SwaySway, the upbeat leader of the flock and his loyal best friend Buhdeuce go on riduckulous adventures together. From eating a loaf of ‘Stank Bread’ and getting lost on the lower yeastside, to record-beaking attempts for most bread deliveries in one day, nothing will stop this duo from making a delivery all while shaking their tail feathers. Breadwinners will air regularly on weekdays at 4:30pm. For fans who can’t wait, the first episode will sneak beak on the Nick App on 15th September. In the series premiere, “Thug Loaf,” when SwaySway and Buhdeuce have to deliver bread to the bad part of Duck Town, they accidentally lock their keys in the Rocket Van and have to befriend a gang of Biker Ducks for help. The Nick App will also play host to the ‘Breadwinners Ducktionary’ where viewers can brush up on their beak lingo. Steve Borst (Teen Titans Go!, MAD) and Gary “Doodles” Di Raffaele (MAD, Metalocalypse) teamed up to produce Breadwinners which was discovered as part of Nickelodeon’s 2012 Animated Shorts Program. -

Watching Television with Friends: Tween Girls' Inclusion Of

WATCHING TELEVISION WITH FRIENDS: TWEEN GIRLS’ INCLUSION OF TELEVISUAL MATERIAL IN FRIENDSHIP by CYNTHIA MICHIELLE MAURER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Childhood Studies written under the direction of Daniel Thomas Cook and approved by ______________________________ Daniel T. Cook ______________________________ Anna Beresin ______________________________ Todd Wolfson Camden, New Jersey May 2016 ABSTRACT Watching Television with Friends: Tween Girls’ Inclusion of Televisual Material in Friendship By CYNTHIA MICHIELLE MAURER Dissertation Director: Daniel Thomas Cook This qualitative work examines the role of tween live-action television shows in the friendships of four tween girls, providing insight into the use of televisual material in peer interactions. Over the course of one year and with the use of a video camera, I recorded, observed, hung out and watched television with the girls in the informal setting of a friend’s house. I found that friendship informs and filters understandings and use of tween television in daily conversations with friends. Using Erving Goffman’s theory of facework as a starting point, I introduce a new theoretical framework called friendship work to locate, examine, and understand how friendship is enacted on a granular level. Friendship work considers how an individual positions herself for her own needs before acknowledging the needs of her friends, and is concerned with both emotive effort and social impact. Through group television viewings, participation in television themed games, and the creation of webisodes, the girls strengthen, maintain, and diminish previously established bonds. -

British Sky Broadcasting Group Plc Annual Report 2009 U07039 1010 P1-2:BSKYB 7/8/09 22:08 Page 1 Bleed: 2.647 Mm Scale: 100%

British Sky Broadcasting Group plc Annual Report 2009 U07039 1010 p1-2:BSKYB 7/8/09 22:08 Page 1 Bleed: 2.647mm Scale: 100% Table of contents Chairman’s statement 3 Directors’ report – review of the business Chief Executive Officer’s statement 4 Our performance 6 The business, its objectives and its strategy 8 Corporate responsibility 23 People 25 Principal risks and uncertainties 27 Government regulation 30 Directors’ report – financial review Introduction 39 Financial and operating review 40 Property 49 Directors’ report – governance Board of Directors and senior management 50 Corporate governance report 52 Report on Directors’ remuneration 58 Other governance and statutory disclosures 67 Consolidated financial statements Statement of Directors’ responsibility 69 Auditors’ report 70 Consolidated financial statements 71 Group financial record 119 Shareholder information 121 Glossary of terms 130 Form 20-F cross reference guide 132 This constitutes the Annual Report of British Sky Broadcasting Group plc (the ‘‘Company’’) in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (‘‘IFRS’’) and with those parts of the Companies Act 2006 applicable to companies reporting under IFRS and is dated 29 July 2009. This document also contains information set out within the Company’s Annual Report to be filed on Form 20-F in accordance with the requirements of the United States (“US”) Securities and Exchange Commission (the “SEC”). However, this information may be updated or supplemented at the time of filing of that document with the SEC or later amended if necessary. This Annual Report makes references to various Company websites. The information on our websites shall not be deemed to be part of, or incorporated by reference into, this Annual Report. -

Davis Model United Nations Conference Xvii Crisis: Avatar

Crisis: Avatar Davis Model United Nations Conference XVII May 18-19, 2019 University of California, Davis DAVIS MODEL UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE XVII CRISIS: AVATAR The following content was developed by members of the Davis Model United Nations conference planning team for the sole purpose of framing delegate discussions and debate at the conference and does not represent any official position of the University or anyone engaged in preparing the materials. Delegates should use this information to guide their research and preparation for the conference but should not assume that it represents a complete analysis of the issues under discussion. The materials should not be reproduced, circulated or distributed for any purpose other than as may be required in order to prepare for the conference. MAY 18-19, 2019 1 DAVIS MODEL UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE XVII CRISIS: AVATAR Letter from the Chair and Crisis Director Esteemed Delegates, Welcome to the 2019 Davis Model United Conference (DMUNC)! We have the pleasure to introduce you to the Avatar the Last Airbender Crisis Committee. My name is Aislinn Matagulay and I will be your Head Chair for this year’s DMUNC. I am a freshman here at UC Davis. I have found a great sense of community in Davis’ MUN club. I was the Chief of Staff at AggieMUN, our collegiate conference and had a wonderful time working with the staff and competitors to make it a fun conference. I am looking forward to the rest of the year to compete in conferences across California and to host you all at DMUNC in May! My name is Thais Terrien and I will be your Crisis Director for this year’s DMUNC. -

Avatar: the Last Airbender

S H U M U N X X I I / / A P R I L 1 0 - 1 1 , 2 0 2 1 AVATAR: THE LAST AIRBENDER B A C K G R O U N D G U I D E D I R E C T E D B Y T I M D Z I E K A N A N D G E O R G E S C H M I D T Avatar: The Last Airbender 1 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR, KACIE Hello Delegates, Welcome to SHUMUN XXI! My name is Kacie Wright (She/Her/Hers), and I will be your chair for the Avatar: The Last Airbender committee. I am currently a sophomore at Seton Hall University, majoring in both Diplomacy and Italian Studies. I am originally from San Diego, California. In high school, I studied Italian for four years and I was able to participate in my high school’s exchange program twice. Here at Seton Hall, I am a part of Seton Hall United Nations Association (SHUNA), our Model United Nations team, I am a member of the Alpha Omicron Pi fraternity, and I am part of the Italian Student Union. I plan to finish my degree at Seton Hall, join the Peace Corps after graduation, and then work for a non-profit organization abroad. Eventually, I want to start my own non-profit organization abroad that helps with community development in communities that are often devastated by conflict and destruction. This committee takes place in the Avatar: The Last Airbender universe, one month after the end of the Hundred Year War. -

Nickelodeon's Groundbreaking Hit Comedy Icarly Concludes Its Five-Season Run with a Special Hour-Long Series Finale Event, Friday, Nov

Nickelodeon's Groundbreaking Hit Comedy iCarly Concludes Its Five-season Run With A Special Hour-long Series Finale Event, Friday, Nov. 23, At 8 P.M. (ET/PT) Carly Shay's Air Force Colonel Father Appears for First Time in Emotional Culmination of Beloved Series SANTA MONICA, Calif., Nov. 14, 2012 /PRNewswire/ -- Nickelodeon's groundbreaking and beloved hit comedy, iCarly, which has entertained millions of kids and made random dancing and spaghetti tacos pop culture phenomenons, will end its five- season run with an unforgettable hour-long series finale event on Nickelodeon Friday, Nov. 23, at 8 p.m. (ET/PT) . (Photo: http://photos.prnewswire.com/prnh/20121114/NY13645 ) In "iGoodbye," Spencer (Jerry Trainor) offers to take Carly (Miranda Cosgrove) to the Air Force father-daughter dance when their dad, Colonel Shay, isn't able to accompany her because of his overseas deployment. When Spencer gets sick and can't take her, Freddie (Nathan Kress) and Gibby (Noah Munck) try to cheer Carly up by offering to go with her. Colonel Shay surprises everyone when he arrives just in time to take Carly to the dance. When they return from their wonderful evening together, Carly is disappointed to learn her dad must return to Italy that evening and she is faced with a very difficult decision. "iCarly has been a truly definitional show that was the first to connect the web and TV into the fabric of its story-telling, and we are so very proud of it and everyone who worked on it," said Cyma Zarghami, President, Nickelodeon Group. -

2012 Conference Program

WEDNESDAY 1 IMAGINATION IS THE 21ST CENTURY TECHNOLOGY AUGUST 8-11, 2012 WELCOME Welcome to Columbia College Chicago and the 2012 University Film and Video Association Conference. We are very excited to have Peter Sims, author of Little Bets: How Breakthrough Ideas Emerge From Small Discoveries, as our keynote speaker. Peter’s presentation on the morning of Wednesday August 8 will set the context for the overall conference focus on creativity and imagination in film and video education. The numerous panel discussions and presentations of work to follow will summarize the current state of our field and offer opportunities to explore future directions. This year we have a high level of participation from vendors servicing our field who will present the latest technologies, products, and services that are central to how we teach everything from theory and critical studies to hands-on screen production. Of course, Chicago is one of the world’s greatest modern cities, and the Columbia College campus is ideally placed in the South Loop for access to Lake Michigan and Grant Park with easy connections to the music and theater venues for which the city is so well known. We hope you have a stimulating and enjoyable time at the 2012 Conference. Bruce Sheridan Professor & Chair, Film & Video Department Columbia College Chicago 2 WEDNESDAY WEDNESDAY 3 WE WOULD LIKE TO THANK OUR GENEROUS COFFEE BREAKS FOR THE CONFERENCE WILL BE SPONSORS FOR THEIR SUPPORT OF UFVA 2012. HELD ON THE 8TH FLOOR AMONG THE EXHIBIT PLEASE BE SURE TO VISIT THEIR BOOTHS. BOOTHS AND HAVE BEEN GENEROUSLY SPONSORED BY ENTERTAINMENT PARTNERS. -

Animating Race the Production and Ascription of Asian-Ness in the Animation of Avatar: the Last Airbender and the Legend of Korra

Animating Race The Production and Ascription of Asian-ness in the Animation of Avatar: The Last Airbender and The Legend of Korra Francis M. Agnoli Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of East Anglia School of Art, Media and American Studies April 2020 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. 2 Abstract How and by what means is race ascribed to an animated body? My thesis addresses this question by reconstructing the production narratives around the Nickelodeon television series Avatar: The Last Airbender (2005-08) and its sequel The Legend of Korra (2012-14). Through original and preexisting interviews, I determine how the ascription of race occurs at every stage of production. To do so, I triangulate theories related to race as a social construct, using a definition composed by sociologists Matthew Desmond and Mustafa Emirbayer; re-presentations of the body in animation, drawing upon art historian Nicholas Mirzoeff’s concept of the bodyscape; and the cinematic voice as described by film scholars Rick Altman, Mary Ann Doane, Michel Chion, and Gianluca Sergi. Even production processes not directly related to character design, animation, or performance contribute to the ascription of race. Therefore, this thesis also references writings on culture, such as those on cultural appropriation, cultural flow/traffic, and transculturation; fantasy, an impulse to break away from mimesis; and realist animation conventions, which relates to Paul Wells’ concept of hyper-realism.